Meredith Sue Willis's Books for Readers 238-240

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Current Issue

Books for Readers # 238

February 24 , 2025

Detail of cover of Shirley Jackson's We Have Always Lived in the Castle; Anne McCaffrey; Leila Slimani; Cherrie Moraga; Percival Everett; Edith Wharton

CONTENTS

Back Issues

Announcements

Book Reviews

Good Reading Online

Especially for Writers

Obituaries

BOOK REVIEWS

Unless otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW.

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

The Post Man Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain

The Stranger by Albert Camus

The Alienist by Caleb Carr

Democracy Needs Religion by Hartmut Rosa Reviewed by Joe Chuman

James by Percival Everett

The Blessing Way, Dance Hall of the Dead , Listening Woman, People of Darkness , and Ghostway, by Tony Hillerman

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Unknown Man # 89 by Elmore Leonard

Dragonflight by Anne McCaffrey

Absolution by Alice McDermott

Shadows of Tyranny by Ken McGoogan Reviewed by Fay Martin

Waiting in the Wings: Portrait of A Queer Motherhood by Cherrie Moraga

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

Dreams Like Thunder by Diane Simmons

The Perfect Nanny by Leila Slimani

Wings of Fire: the Dragonet Prophecy by Tui T. Sutherland

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Books for Readers is still soliciting reading suggestions and reviews of all kinds of books. Be expansive, and send me your thoughts in essay form; or write something short you can use as an Amazon.com review and send to me for this publications as well.

I tend to review older books that I missed along the way as well as books from small and indie presses that deserve more attention. I believe we desperately need alternatives to the handful of remaining (and way too powerful) Big Book Reviews. These publications, like all of us, have limited angles of vision. The antidote it seems clear to me, is lots of places sharing other world views and ideas. Let's spread the word on what we're reading.

Send me your literary news too. Be sure to check out Announcements and Good Reading Online.

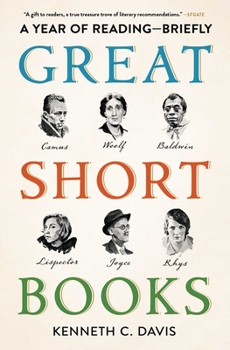

I am coming to the end of Kenneth C. Davis's excellent Great Short Books: A Year of Reading--Briefly. I don't take many classes these days, but I look for guidance in my reading. I had already read and even reread quite a few of the books Davis recommends (The Great Gatsby, for example), but there were also some great discoveries for me (See my review of We Have Always Lived in the Castle in this issue). I reread several like Death in Venice and was so glad I did. Things you read as a twenty-somthing have an entirely different quality forty and more years later.

For one thing, even though I was certain smarter and sharper in many ways back then, I was always panicked that I wouldn't "get" something that others considered "great." What a relief to be relaxed as I read. And yeah, sometimes I don't get something, but now I know there's no one It. I actually seem to read with more facility now. I trust myself as a reader more, and I think I'm more willing to open myself to the the book's work. Reading is to one extent or another opening yourself to another person's viewpoint, concerns, passions.

One last point, related a little. I have notes here on two Margaret Atwood novels, Alias Grace and Surfacing (the latter another Kenneth C. Davis suggestion). In my journal I questioned myself about why I don't seem to respond to Margaret Atwood the way I expected to. I find myself more moved by the work of Alice Munro (grouping them by generation, fame, and Canadian citizenship). Munro, the late Nobel prize winner has been discussed a lot lately after her daughter writing about Munro's husband who molested her, the daughter. Apparently Munro never took action against him. I've been in a number of heated conversations about this, and whether such biographical knowledge ruins one's perception of a writer's work. And the truth is, for me, even with all that, I still feel more for Munro's work than Atwood's.

They are both mostly bleak and and often depressing, but Munro's depressing stories usually leave me (mysteriously) uplifted. When I read Atwood material, I admire, always finish the books, but walk away oddly untouched.

REVIEWS

Dreams Like Thunder by Diane Simmons

This wonderful short book is at once an affectionate and humorous look at a lonely, highly imaginative eleven year old's life and the richly rendered world of a high desert farm in Eastern Oregon. It is, in fact, so eastern that the nearest city is Boise, Idaho. There is haying with sounds and smells and black dust circles around the workers' eyes, and there is our girl Alberta's delight in her adult friends who do the haying. She especially loves her father, a World War II ace pilot and flying instructor, who works alongside the hired men men.

Alberta's mother, on the other hand, is unhappy on the farm and spends much of each day lying in the sun with aluminum foil disks over her eyes. She was an Alabama Southern belle who now finds herself in the middle of nowhere living next door to her mother-in-law, who is tough and religious and does not agree about how to raise a daughter.

The story line is about the coming visit of Alberta's mother's cousin and her daughter, who is Alberta's age. The close third-person narration alternates character sketches of the people around Alberta with splendid moments of being in the out-of-doors and also a string of fantasies that she spins about the much-anticipated visit of cousin Martha Lee. She makes up stories of how they will be inseparable and become stewardesses and fly to Paris.

While she is planning where to take Martha Lee around the farm, she has a run-in with the "not-all-there" neighbor man who she is afraid is going to shoot her with his ever-present gun while she is walking a fort she built herself. There is so much hope and anticipation around the arrival of the guests, that this reader of too many novels assumed some disaster was coming: child molestation or the guests would cancel or Martha Lee would turn out to be a pill.

But this is a Diane Simmons world that is above all grounded in life and the superior power of human imagination. The guests arrive safely, and while Martha Lee is afraid of farm animals, she is plenty feisty in her own odd-ball way. The girls explore and spy and come up with an idea about writing fake notes about the life and death of a woman whose name they get from her tombstone. And the fake notes are accepted for publication by the copy-hungry editor of the local newspaper!

I love the play between the real and the imagined here. A practical joke that requires writing skill and a grasp of real life.

In the background, swirling around, are stories of the pioneer generation in Alberta's family. She hears about the murder of indigenous people that is told as a legend from the far past, as is the treatment of Chinese workers in the local gold mines. History is thus largely off stage in Alberta's world, but the tales and legends give the child's life a deep perspective that enhances and locates it in time as well as place.

The ending, with its hilarious plot twist but no disaster, is priceless.

And finally I'd like to offer heartfelt thanks to Red Hen Press for bringing this book back into print.

The Perfect Nanny by Leila Slimani

Well, this one was not fun. The first line tells you that some young children have been murdered, the special nightmare of the working mother. The rest of the novel is about why it happened. I had to stop and go read something else for a while. The Nanny of the novel and her breakdown make a solid study of what

might have happened to such a woman plagued by psychological discord, a brutal husband, and destitution when he dies. She doesn't have the tools to deal with a difficult child of her own, but she discovers she can care extremely well for other peoples' children. So much is stacked against her: her passion of her charges, for example. All this is extraordinarily well imagined by Slimani.

Even so, at various points, I kept pulling myself back a little and saying, Yes, but you, author, are imagining this–why are you imagining this instead of something different?

Slimani imagines the horror of the victims, and the horror of the killer, but she never attempts to capture the birth mother's actual feelings when she discovers the bodies--that is treated as an hour-long scream. I find that a little odd: why is the person most like herself (based on the biographical material I found on the author) given a terrible moment that we experience from a distance?

Or maybe the story is just too much for me.

Read it for the technical and imaginative brilliance, but don't expect to have fun.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Art by Thomas Ott

This is horror too, I guess, creepy, but Shirley Jackson creepy: very funny and fond of its characters. It isn't supernatural, nor is it quite this world we live in. Merricat (Mary Katherine) he narrator is supposed to be 18, but sounds like one of the 12 year old prodigies like Frankie in Member of the Wedding. The situation is that Merricat lives with her older sister Constance and great-uncle Julian in a big house on the outskirts of a little Vermont town (like the setting for "The Lottery" and other of Jackson's works). A few years earlier, the other members of the rather aristocratic and snobbish family died in an arsenic poisoning.

Merricat's sister was generally blamed, but acquitted in a traumatic trial.

Merricat's main duty for the household is to walk to town twice a week for groceries. The townspeople stare and sneer and recite little nasty verses about poisoning. Older sister Constance doesn't leave the house. There are, of course, secrets and surprises. Everything in Merricat and Constance and Julian's orderly lives is overturned after Cousin Charley comes to visit and tries to make changes, particularly to seduce dear Constance. He is the destroyer, in Merricat's opinion, of a very happy household.

There is a house fire, and the whole town comes out to watch. The fire fighters put the fire out because, they say, that's what firemen do, but the townspeople trash the house. It's all pretty appalling, and there are no really admirable people on any side. Maybe Merricat's pet Jonas the cat, and from time to time Uncle Julian. But because of the seductive and amusing voice of Mary Katherine, we are totally cheering for her side, however well we know her and what she's capable of by the end of the novel.

Such a shivery delight to be in Jackson's idea of small town America!

A 2010 NY Times discussion of the Library of American edition of Jackson gives a good overview of her work: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/29/books/review/Rafferty-t.html

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

I wrote in the introduction to this issue about how I respect and admire Atwood's work and am always sufficiently entertained to keep reading, it somehow usually leaves me cold. Maybe it's me. There is

something missing for me in her characters, although she is far too good a writer for me to be clear about what it is.

In this novel, based on a real double murder in the middle of the nineteenth century, at the time when, in the USA, the Civil War was about to break out, a woman named Grace Mark is convicted of murder. She is an immigrant servant who has lost touch with her family and has fallen in with a man who instigates the murders and is hanged. Grace is convicted, but saved from hanging by a clever lawyer, and then spends thirty years in prison and insane asylums before being released. She gets a modicum of a happy ending. She is also the only character in the book who-- mysterious and possibly split-personality as she may be--has a kind of thoughtful dignity that makes her attractive.

The other main character is Dr. Simon Jordan, a young man who is ambitious about starting his own treatment of the insane in a (he hopes) profitable institution. He has Ideas, and he is studying Grace. He is sexist and classist and, more damning for a character in a novel, fatuous. I don't like him or most of the others. Simon is a twit, Simon's landlady is at once a victim and unpleasantly whining and clinging, the murderer McDermott is a brute, Grace's various bosses are beyond selfish, and her erstwhile friend Jeremy the peddler never stays in one role long enough to develop much--actually, he seems wasted to me altogether.

Even Grace's friend Mary, who lives in her imagination, may have a vengeful side. None of those things are impossible in fiction as far as me identifying with the characters--I am as fond of Elmore Leonard's assassins and jerks as I am of his heroes-- but in this book, except for Grace herself, there are mostly people to repel you.

On the other hand, it's a darn good story and the scene setting is really good--the material culture of mid nineteenth century Canada.

Surfacing by Margaret Atwood

This 1973 novel is again solid and well crafted and certainly superior to most popular literature. Surfacing is about the lives of women in the nineteen fifties and early sixties--catering to despicable men (whether or not they recognize it). Sexual frustrations is always the fault of the women. The women do the cooking and nurturing with no one even noticing.

Atwood was known first as a prolific poet. She wrote this at the age of 33 or so--a very young woman, very angry about the changes in the world and the bad influence of Americanization whom the main character identifies in a lot of Canadians. She says a lot about the wilderness and respect for the animals and land, but doesn't say much about the people who preceded the French and British.

The story has couples coming to a lake in northern Quebec to see the cabin where the narrator grew up half of every year half the year. Her parents are dead, or rather, her mother is dead and her father is probably dead, but possibly not. Perhaps he went crazy and ran off into the "bush."

The narrator does this herself at the end of the book--has either a spiritual epiphany or a breakdown. She runs from the people she came with. She won't walk into human made enclosures or eat food in cans.. In very sixties fashion, though--and of course the sixties really lasted at least till the fall of Saigon in 1975--insanity is often a synonym for extreme freedom (think of the writing of R.D.Laing who defined schizophrenia as “an adaptive response to a chaotic and disordered society.”)

So she runs into the forest, rips up her clothes, burns her memorabilia, refuses to go back to civilization, then sees the ghosts of her parents. Finally, she decides they would prefer her and her fetus (about 48 hours along) to survive, and she begins to move into the future.

I believe we are supposed to cheer, but I find myself not really trusting her decisions.

Of course, Atwood is brilliant, and she generally writes exquisitely. Also, she knows a lot about the flora and fauna and weather of the Canadian north.

And if nothing else, this would be an excellent introduction to the seventies themes of second wave feminist writers.

James by Percival Everett

One of my favorite ways to evaluate a book is to consider whether the ending is as good as the promise of the beginning.

Percival Everett's popular James aces the test. The ending fits what has come before, and is satisfying and well earned. I'm glad Percival Everett's career--long, serious, and literary--has taken off in a big way.

James has a lot of nice touches like catching a giant catfish for dinner by wiggling your fingers and almost getting your arm swallowed; the clever use of the traveling minstrels and the Duke and the King from Huckleberry Finn. All fun, exciting, clever. The one thing that I am not quite satisfied by was the oddity of having the slaves when they are with each other, speak a kind of standard twentieth century Midwestern newscaster English. I totally believe and liked the idea that the enslaved people exaggerated their dialect in the presence of the "massas," and I certainly liked at least for this story that Jim/James could read-- read Voltaire, John Locke, Rousseau and more.

But Huck and the various crackers speak dialect, so why don't the poor black people? I guess I should just accept the magical realism of this, as I accepted James freeing a whole breeding farm full of enslaved people. It did stimulate me to wonder what indeed the enslaved people DID speak to one another-- I imagine it full of figures of speech and metaphors but not plain-Jane newscaster English.

But that's all quibbling. The relationship between Jim/James and Huck was wonderful, and the action and adventure, and the skill of how he ended it.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

So then I had to reread Huckleberry Finn. It was my first reread since what? high school? My early twenties? Much easier reading than my last try--how did getting old and slow make me a better reader of nineteenth century books? Maybe I'm just more relaxed and experienced at the complex sentences?

The book whipped me back and forth between real enjoyment and admiration and being appalled at some of Twain's choices--Tom Sawyer and his cruel practical joking is of a piece with the good-old-boy American men that one has come to loathe. All the life on the river was wonderful, and yes the frequent use of the the n-word grated and weighed on me.

A little superficial survey found the book defended by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jamelle Bouie. Percival Everett thanks Twain in his intro to James. Interesting indeed that these people see the strength of Jim's character central to Twain's novel. There is also an excellent Toni Morrison essay on Huck Finn for which I had a lot of trouble getting a citation--I found some professor's .pdf of the essay for a class, and Google's little robot assistant asserts it's from the NYTimes book review, but I'm not convinced that is true--we have to keep in mind that the little AI gremlins hallucinate.

At any rate, Morrison spends time on Jim as a good father to Huck--which makes me wonder if this is where Everett got the idea for his big reveal in James.

The King and the Duke were so nasty and exaggerated (I hope) and the insane caricatured "Southren" Grangefords all getting slaughtered by their enemies. What a brutal parody of Southern gentry that was.

The final fifteen or twenty per cent though--the return of Tom Sawyer-- was appalling. I didn't like the elaborate "fun," and I didn't' like Tom, and I didn't like Huck's knuckling under to Tom let alone how they torture Jim in chains and completely disrupt the Phelps family with rats and snakes and spiders.

Tom is really a middle class brute in his creative, imaginative torture. The ending--Tom getting shot and his wound infected, then Jim sacrificing himself back to slavery-- he thinks-- for sticking with the sick Tom, and then the reveal that Jim has been freed, and Tom knew it! More torture. Yes, Twain's novel is deep and complex, and he was also making a living by his humor--but I'm still left confounded. Which Morrison says is what literature's supposed to do to/for us.

Well, maybe.

Toni Morrison's essay on "The Adventures Huckleberry Finn" , an introduction to a 1996 edition of Huck Finn, is extremely worth reading. I have a link to it here.

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Oh, I do like the world as Edith Wharton creates it, and she does a great scene. She isn't as subtle as her dear friend Henry James (he perceived her as more than a little overwhelming, likely to come and sweep him up for a motor car ride), but for all of his subtlety, her scenes are at least as good, and her portrait of a specific time and place superior. (James of course liked best, especially in his late years, to abstract his people from a lot of daily life).

The first part of The Age of Innocence is stunning. The authorial voice is looking back to the mid 1800's,

commenting on how different it was from the "now" of the early twentieth century. Her authorial voice is a comfortable guide, making sometimes gentle, sometimes not, fun of the old protestant New York aristocracy with its terrible limitations on women– and, of course, its many wealthy women who manages to master their world anyhow, for good or for evil.

We follow young Newland Archer. He has his criticisms of the milieu. and he likes progressive literature and art. Art, society, Europe versus America, the preservation of virgin virtue--the book is in constant conversation with so much of Henry James. It speaks about many of the same themes, but Wharton is always a little clearer, a little louder--a little more open to dramatizing vulgarity.

For example, we learn in so many words, Archer's own, that he has sown his wild oats with a married society woman. He is in no way ashamed--feels indeed that he owes this knowledge to the innocent, virginal young woman he is marrying-- who he intends to mold into exactly the woman he imagines. He has chosen May Welland. who is, he believes the very flower of Old New York, and he expects to have her join him in some mild push back against Society, and of course in enjoying art in Europe.

Then May's cousin, the Countess Olenska arrives in town. She has left her husband, causing a scandal. Love, passion, hypocrisy and major manipulations and efforts at persuasion ensue.

The real story is what boundaries are broken and reset, and who really wins. Old New York wins the battle, but loses the war as we see in the early twentieth century part when Archer is a grandfather gazing with amazement at the world where he lives now.

The Alienist by Caleb Carr

I thought at first this was putting all its emphasis on the researched background of New York City around the turn of the twentieth century. That was interesting, but the story got better and better as it went along. I wonder if this was Caleb Cobb learning how to write a novel? He was an experienced nonfiction writer and the child of a founding member of the Beats (friend of Kerouac and Ginsberg).

This is, however, his first novel. By the second half it rolls along very nicely. He has good characters, especially his genius child psychiatrist Laszlo Kreizler (the alienist ) and a journalist narrator John Schuyler Moore who is an excellent guide to the watering holes and other delights of the city. Also part of the detecting crew is Sarah Howard who wants to be a police officer, and Theodore Roosevelt, commissioner of the New York City police at the time

Other colorful characters include some very bad cops and an underworld of "boy-whores" and other prostitutes, gangsters and a serial killer who preys particularly on the boys. Kreizler is determined to chase him down by figuring out his psychology, and this is elaborate and mostly fun, and ends with an excellent climactic scene on the parapet of the old Reservoir that was soon to be replaced by the New York Public library and Bryant Park.

Looking back at my reading experience, a day later, I realize I really liked it. Not that it needs my recommendation–it was a big best seller in 1994.

The Post Man Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain

Much better than I feared: a 1930's Depression novel, first big best selling (and "Banned in Boston") noir novel. Along with Chandler and Hammett, Cain invented the genre. He was another alcoholic who wrote just a couple of

good books-- this one, Mildred Pierce, and Double Indemnity, all of which were made into classic movies.

I agreed with the general praise of its directness, its sharp dialogue. The characters have little in the way of morality, but are still attractive. There's a barren landscape and national poverty in the background making everyone out to make a buck or marry one. Sex isn't graphic as far as action goes, but there is no question there is a lot going on in bed. Cora a couple of times says, "Rip me!" which is more than a little disturbing, maybe more now than back then. It is never clear if we're talking about blouses or rough intercourse.

Cora and Frank's plans to kill her husband are sloppy and never for a moment look likely to succeed. Actually, they try twice, and there's a complicated trial and a very clever lawyer. Cora and Frank are constantly on the verge of turning on one another, and there is a final, real not staged, accident that gives us the real noir ending.

I don't think the plot bears a lot of examination, but the momentum and sexual passion make it surely rock and roll. I was surprised by how much I liked it. Lively and hot and heavy and dripping with doom.

Absolution by Alice McDermott

Highly praised, highly recommended, and I can only add my appreciation to the chorus. This one, like my favorite of her work so far, Charming Billy, is an indirectly told study of character. Charlene, an engineer's wife in Vietnam in the early sixties is a bit of a rebel, at least on the surface, a do-gooder, a mother, a woman who mutters her iconoclastic remarks in private and breaks rules sub rosa. There's a lot about Americans in Saigon and the pretty appalling attitudes of men toward women and of women toward themselves and each other.

Two women tell it, a newlywed protegee of Charlene's, and Charlene's daughter. There is a lot about parenting: about miscarriages and marriages and adoption, and the twisting of even good intentions under imperialism. It is thus also about the Vietnam war. I probably liked Charming Billy better, but my second favorite Alice McDermott novel is very high on my general list.

Unknown Man # 89 by Elmore Leonard

This is fairly early Leonard (1977), when he wrote real prose instead of movie scenarios. In this novel a Detroit process server who is a recovering alcoholic meets a current alcoholic, and they work on their problems together and maybe fall in love.

There are some charming bad guys, including one who, he convinces us, discovered patience in prison--but then waits a little too long. The other isn't a professional killer, but has no problem with doing what it takes to reach his goals. He comes to Detroit from New Orleans and spends a lot of time complaining about the weather and eating the best food he can find in town. He is running a semi-legitimate scam to find people who don't know they own old stocks that have improved in value, and then take most of the recovered money for himself.

The violence feels appropriate, and the shot gun is the real power weapon.

Leonard was having a lot of fun when he wrote this.

Waiting in the Wings: Portrait of A Queer Motherhood by Cherrie Moraga

This is a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of a book with a new forward by the author and an epilog by the young man who is the baby in the story--which is a story of chosen motherhood. Moraga, a self-identified Chicana butch Lesbian, has a baby who is so premature head has to spend three grueling months in the hospital living through blockages and infections and major surgeries. The trials Moraga and her partner undergo just to get in and out of the hospital are appalling. This was twenty five years ago, and one hopes hospitals do better with so-called nontraditional families now, but we can't be sanguine about that now, if ever.

Moraga's ability to write once Rafael Angel is home is compromised and changed, and familiar to any woman who loves her child but is appalled at how she has lost her privacy, her inner life, all of the things she had that made her who she was/is. In the end, it is a wonderful memoir that brings together politically important ideas and everyday family love.

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

This is a reread for me–a book I bought so long ago that its pages are crumbling. I remember in my first reading that I looked for the good guys–the Gnostics didn't denigrate women in person on in theology, the orthodox were rigid, anti-woman, hierarchical; the Gnostics were (rather like Buddhists) inward looking for the spiritual; the orthodox were more interested in political control of their adherents and clergy-administered religion. The Gnostics were rebels, refused to accept the orthodox orders and the orthodox canon of New Testament books.

But it turns out, as always, that it wasn't so clear. The Gnostics were also elitist (only the so-called spiritually "mature" got to be part of the in crowd), and they had a weirdly elaborate cosmology with a God who was only to create while the real power was mysteriously behind that one.

Meanwhile the orthodox "catholic" church was focused on building a structure that would last for millennia and had a simple confession that included anyone who wanted to be part of it. Maybe the big difference is that at this reading I'm beginning a separate myself from "teams."

In any case, Pagels and her Gnostics certainly complicate what Christianity started out as–the Vatican must have hated it in when the scrolls of ancient alternative texts to the canon were found in 1945 (the "Nag Hammadi Library" of scrolls in Coptic translations), sold, resold, and finally publicized in a facsimile edition between 1972 and 1977.

The belief is that some monks, when ordered by the hierarchy to get rid of all non-canonic books, preserved these scrolls in a jar and hid them in a cave in an arid climate. Pagels looks at all this pretty thoroughly for a small book and makes the case that "many Gnostics, like many artists, search for interior self-knowledge as the key to 'understanding universal truths'" (p. 161-62 New York: Vintage 1981).

Liberating for me, to get a sense of how it all went down, how differently people interpreted Jesus and the religion built around him and his teachings.

Shadows of Tyranny by Ken McGoogan Reviewed by Fay Martin

Ken McGoogan’s seventeenth book, Shadows of Tyranny: Defending Democracy in an Age of Dictatorship, is a ‘cautionary non-fiction’ approach to capturing the current political reality. When he wrote it, Trump had not yet mused and then doubled down on the idea of Canada becoming the USA’s 51st state. He had not yet referred to Canada’s Prime Minister as Governor, and promised to annex Canada through economic war. In fact, Trump was not yet [president] when this book hit the shelves in August 2024.

So it is a chillingly prescient book. McGoogan paints the pre-WW2 world in detail, exposing alarming parallels with the current growth of demagoguery and authoritarianism around the world, including in the USA. He does not articulate the obvious. He does not finger wag. He does not explore the intricacies of fascism vs Stalinism vs communism. But his characters do.

Somebody has said and been cited that history doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes. This is a book of rhymes. McGoogan follows the political figures of pre-WW2 and the war as it unfolded in full context, but he also includes the supporting and contrasting cast of players. Central among them are writers – journalists, novelists, dystopians, poets, playwrights, including Orwell top of the list had he not died so young, Andre Malraux, Hanna Arendt, Drien la Rochelle, Mathew Halton, Dorothy Thompson, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Martha Gelhorn (twice the man Hemingway was, his favourite non-favourite.) McGoogan thinks that how reality is named determines how it is experienced, and writers therefore play a direct and very significant role in how reality unfolds. He is unjudgmental about how the perception of wordsmiths changed over time when it is based on engagement. He has no mercy for writers who covered the war or the precedents to war from the hotel bar.

McGoogan humanizes the cost of war to not only the soldiers, but also to those who loved them, and those on whose land they fought, whose food they ate, whose lives they displaced. And those who played the back-stage roles, often female: the nurses, the spies, the resistance workers, the code-breakers, those who stepped up to keep society running in the absence of a generation of men and of focus on everyday necessity.

If there is an overarching narrative in this book, it is the importance of words in structuring resistance. McGoogan draws reality in stark outline with fire-hose intensity. His commentary is limited to the occasional ‘Ya think?’ wink that invites the reader to make what they will of the facts he has delivered, including finding contrary or ameliorating facts if they are so inclined. He expects of readers what he expected of writers who covered the war, that they leave the safety of the hotel bar and venture into the dangerous complexity of the larger world.

McGoogan predicts the rhyme of history in early reactions to the rise of authoritarianism – appeasement, not taking risk seriously, confusion between what the true evil is that needs to be confronted, a political Tower of Babel as evil embeds. His epilogue is entitled: Where is our Churchill? Where indeed.

If this book makes you think (as it did me) that maybe we are on the brink of war again, you might also be interested in (re)reading Vera Britten’s Testament of Youth, or seeing a chilling film adaptation of the same name, available free on CBCGem.ca. Britten decries the First World War’s ruination of a generation of men, from the perspective of a privileged woman who nursed wrecked soldiers from both sides of the war, in repurposed aristocratic homes in Britain and in the mud of France. She, too, believes in resistance and resilience through words. Writers of our time should take heed.

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Another Great Short Book--this one with Camus' famous declaratory style and the narrator Meursault's flat affect. He mostly seems to want to be precisely honest about what he doesn't feel, or perhaps more precisely doesn't feel the way he is supposed to feel.

The story centers this in his mother's death. he doesn't mourn her, although he goes through an all night vigil for

her at the Home where she lived and died. He drinks coffee with an employee of the Home and offers to share a smoke with him. There's an intense even hallucinatory vividness about these small actions. Everything is moments of being, the power of the senses--especially the Algerian sun.

Camus was 29 when this first novel was published, very committed to his lack of passions, his semi-scientific nouveau roman focus on things. He was awarded the Nobel Prize at 44, died early, all that, but the thing no one says is that while he was brilliant, he was also young.

The story is compact and vigorous. Meursault-- the foreigner, the stranger, the outsider (as the various translations of the title go), spends a day with a brutal friend and the women in their lives. There are altercations with some Arabs who are after Meursault's friend who beat up their sister.

Meursault becomes feverish from sun and probably from a desire to feel what it is like to kill a man, so he does. And from there, the story is about law, prison life, the bizarre courtroom practices of the French in Algeria, and Meursault's observations and insights. He is convicted, mostly based on his lack of expressed feeling at his mother's funeral, and his execution looms.

The novel ends with Meursault yelling at an annoying priest and then experiencing a sudden understanding of life--as if the imminence of death by guillotine makes him finally wake to feeling.

The lack of interest in the murdered man niggles at me, but I was happy to see Meursault awaken.

A Few by Tony Hillerman

What can I say? I like them, and they are very short--and instructive as well as entertaining.

The Blessing Way by Tony Hillerman

This was the first of the Joe Leaphorn novels, and the main character is really a white academic whose name I've already forgotten. This is the one where the editor encouraged Hillerman to enhance Joe Leaphorn. Good decision. Very exciting, believable minor characters, and Leaphorn figuring out what's going on in one place and the white academic in big trouble in another place. Good action, and a complicated plot (supposedly a strong suit of Hillerman's).

A lot hangs on a character known as "the big Navajo" whose hat is stolen and whose Navajo isn't as good as his English. This is interesting, as are the ceremonies. But Berg (the white guy--name came back) is an unbelievable jerk vis-a-vis women. I think Hillerman (at least back in 1970) would have said he was supposed to be, but it really irked my liver–as long as the guy is escaping from a sealed room and getting shot, he's fine, but I wanted to puke over him

and his love interest, whose main role is The Girl.

Dance Hall of the Dead by Tony Hillerman

This one was darker, with the deaths of boys and a creepy anthropologist on a dig. But Joe Leaphorn is good again. He does a lot of tracking, and Hillerman makes it interesting. Leaphorn gets wounded in an interesting way.

There were plot details I didn't bother to go back and work out or even really understand. For me, it's the narrative, of course, and with these books, a kind of anthropological survey and even a travelogue: learning about this place, enjoying the religious distinctions between the Navajo and the Zuñi–and the tensions between the tribes.

I did look up Navajo commentary on Hillerman's novels, and in the beginning, it was generally positive, but I think subsequent generations have been more critical.

Listening Woman by Tony Hillerman

I stopped at least temporarily with the t.v. show and decided to try Hillerman's novels. I read this one first, out of order. They are all short books, and you see his writing style improving rapidly. I probably like best an easy glimpse, not overly challenging, into the world of the Navajo and other Americans who preceded the rest of us.

The last part of this novel is all physical action with Joe Leaphorn struggling with bad guys and a monstrous attack dog and caverns and fire and explosives and guns.

It's smoothly written, and hard not to like Joe with his low key wit and frequent holding back what he's thinking. In this story, an offshoot of the American Indian Movement has turned to terrorism.

I'm pleased to discover a new series.

People of the Darkness by Tony Hillerman

I've been watching the Netflix series Dark Winds, which uses whatever parts of the novels it wants to, and that threw me at first about his book which has Jim Chee for a protagonist and a white teacher named Mary Landon for a love interest. She goes along him on a combination investigation and avoidance of someone looking to kill them–the very blonde assassin. Anyhow, once I got over the confusion from the t.v. show and while I wasn't thrilled with Mary Landon's role in the story, Jim Chee's attractive self-examination over his reaction to her and HER reactions is well done. I continue to be a little nervous about how the Navajos and others appreciated Hillerman's portrayal of their lives and ways.

Ghostway by Tony Hillerman

Finished another Hillerman last night: Ghostway (?) This one starred Jim Chee, and I liked its efficiency and landscapes and, again, the Navajo lore.

Dragonflight by Anne McCaffrey

This was the first of a popular dragon series--an early one: the world of Pern, dragons and dragonriders, time travel. I'd read about it, and was mildly disappointed after

expecting this to be really engrossing. It was instead thin in places, and even tiresome--essentailly not as well written as I'd hoped.

Apparently, McCaffrey considered her work science fiction with a fantasy tone. She sounds like she was a decent person, working with her son and others on some of her later books and finally turning the series over to him.

Well, maybe I'll try her again--if I get really hungry for dragons. I should say that in 1987, Locus ranked two of the eight Pern novels among the "All-Time Best Fantasy Novels", based on a poll of subscribers. (Dragonflight and The White Dragon).

Commenting on this list, David Pringle called them "arguably science fiction rather than fantasy proper," He called McCaffrey's work part of the planetary romance subgenre of science fiction.

Wings of Fire: the Dragonet Prophecy by Tui T. Sutherland

More dragons. This series is aimed at younger children. I read it because my almost-nine year old grand-daughter was determined to get me to read it! I liked the lovable dragon protagonist Clay a lot. The main characters are all dragons, and there's lots of cheerful violence, mostly dragon-on-dragon. The dragons have rather nasty queens who appear to be Alexander the Great wannabes.

I'm not going to say much about the plot, but it's well done, and somehow having all the protagonists and point of view characters be dragons rather than people seems to be a sort of distancing technique for younger readers. The dragons themselves seem adolescent in the purity of their ambition, adventuring, loving and hating. No need for human history or much nuance, but there is lots to like–the characters, the dragon tribes. Lots of action and friendly squabbling among the good guys. Oh, there are LA some funny little squeaky voiced creatures called "scavengers" who appear to be humans.

Democracy Needs Religion by Hartmut Rosa Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Maintaining that our democracy needs religion seems an idea ill-fitted to our times. In the West at least, religion is not faring well. Western Europe is arguably a post-religious society, with many churches and cathedrals converted to museums or concert halls. In the last several decades, the United States seems to be following Europe in a move toward creating a secular society, witnessed by the rapidly expanding ranks of the unaffiliated. More than 28% of Americans now assert that they do not belong to a house of worship, and this cohort of "nones"

includes growing numbers of agnostics and atheists. "Nones" now exceed the percentage of Americans who are Catholics and evangelical Protestants, making it the largest group on the religious spectrum. The loss of adherents may be a factor in pushing many conservative religionists to the extremes. Christian nationalism is on the rise, and the politicized evangelical churches have been among Donald Trump's most stalwart supporters, without which he could not have attained the White House. If anything, contemporary religion proves itself to be a militant destroyer of democracy, making the title of the book under review at least ironic, if not provocative. Reactionary religion has had a long history of supporting fascist regimes, and it is ominously happening under the direction of Donald Trump. Moreover, rampant sexual abuse in the Catholic Church has been a global phenomenon, undermining its claims to moral authority. And when it comes to abuse, Catholicism does not have a monopoly. The religions have a long, tragic history of complicity with the forces of darkness. Among those whose ethics are guided by decency, religion in our times does not have a good name. The Left has had a long history of condemning religion for its collusion with retrograde political movements.

Democracy Needs Religion by the German sociologist, Hartmut Rosa, is a small book that encompasses large ideas. At fewer than 70 pages, it is the revised and extended publication of a lecture that Rosa gave to the Diocese of Würzburg, Germany in 2022. Rosa's primary concept is what he calls "resonance," and it is the focal idea around which he critiques the malaise of modernity. Resonance is a concept central to Rosa's work and serves as a basis for an earlier work with that title. Democracy Needs Religion briefly applies Rosa's theory of resonance to the revival of democracy, especially in the interpersonal quarters of contemporary life.

Borrowing from Karl Marx and the theorists of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory, Rosa identifies alienation as the primary discontent of modern society. Resonance, which describes a change of consciousness, is proffered as the response to that alienation caused by the structure and rushed tempo of contemporary life.

In Rosa's analysis, society can be described as in a state of "frenetic standstill." Perpetual growth without direction is its prevailing dynamic. As Rosa notes,

"[frenetic standstill] is meant to imply two things. On the one hand, society is accelerating. Indeed, it is frantically rushing ahead; for structural reasons, in fact, it must rush in this way to maintain its structure. On the other hand, however, it has become mired or sclerotic. It has lost the sense of its historical (forward) momentum."

Rosa refers to this condition as "dynamic stabilization," and relentless growth lies at its core. Such accelerated growth, he asserts, is necessary to maintain the status quo. As such, modern society needs to expend more and more energy to maintain existing conditions. The demands built into the structures of late capitalism ensure that we produce and have more: more energy, more expansion, more productivity, more inventiveness, more things, more wants, all moving at a forever accelerating pace. As Rosa concludes,

"I find it truly absurd at this point to speak abstractly of growth without indicating where this growth should be achieved..."

"Even more absurd is the fact that we, as humans, don't even want all this growth because we are greedy and insatiable. We need it because, without growth, we could no longer sustain the entire existing social structure. Growth and acceleration are driven by fear, not by greed."

The relentlessness of accelerated growth results in consequences at both the macro social level and in the lives and consciousness of individuals. Environmental destruction is no doubt its most salient consequence on the planetary level. With regard to the fabric of social relations, Rosa asserts that the condition we are in renders more aggressive our relationship to the world and to each other. "Our relationship to the world is aggressive; we are always in attack mode or alarm mode." Industries, the extractive industries as the prime examples, are acting more and more recklessly in the search for oil and rare earth elements. This aggressive frenzy of perpetual expansion, Rosa asserts, informs our politics. He argues that it is the dynamic underlying our stark divisions and the transformation of political adversaries into perceived enemies.

There is a psychological toll as well. An ethos of relentless growth is experienced in what he identifies as the burnout crisis, which closely correlates to a burgeoning rise in mental illness. Rosa's realism causes him to admit that the modern agenda has given rise to tremendous levels of economic welfare, scientific knowledge, and technological capability. But despite this progress, Rosa concludes that the promises of modernity have not been kept.

The modern world is one of great utility, yet it has left us wanting for experiences fundamental to our sense of well being and our relationship to the world beyond ourselves. A pall pervades society. Growing competition and dwindling resources make the future less promising. Greater knowledge has led to more uncertainty, not less. There is palpable ignorance and skepticism as to how science relates to personal lives. Parents traditionally felt that their children would be better off than themselves: but no longer. At the same time, emergent awareness of historical evils has darkened our appreciation of the past. In Rosa's view, we have lost both the past and the future.

It is apparent that Rosa is a man of the left, and one concludes that he could amply elaborate a political analysis of the oppression and exploitation wrought by neo-liberalism and late capitalism. However, he does not take this direction in this brief work. One concludes that in his view even if economic egalitarianism were achieved, an essential element would remain missing. And this missing dimension, which resonance restores, is the answer to the alienation wrought by the modern circumstances he describes.

Resonance is a mode of experiencing the world around us. Rosa describes it initially as possessing a listening, receptive and responsive heart. Rosa describes resonance in an interview given in January 2017:

"I was looking for a way to save the concept of alienation by defining alienation's true other, so to speak. That's how I arrived at this notion of resonance. You're non-alienated from your work, for example, or from the people you interact with, when you manage to have a responsive, transformative, non-instrumental relationship with them, a resonant relationship. The difference is you don't try to manipulate the other side, which could be a person or an idea or a piece of music or nature, or to control it instrumentally or make it disposable and available. Instead, you try to listen and to answer. And whenever you are in that state of experience, when you listen to some music for example — or when you talk with people or when you do your work right, i.e. when you're in resonance, when you feel that the thing you interact with is important, then it speaks to you, it touches and affects you. So this is the one side of a resonant relationship: You are touched, and affected. But on the other side, you also have the capacity to experience self-efficacy. You reach out to the other side too! That's a relationship which is not instrumental and which is not about control, it's a form of resonance. It's a dialogical relationship, which we can never bring about merely instrumentally." (To read the interview in full, you may click here.)

In Rosa's current work, he elaborates on this concept:

"Whenever resonance does take place-whenever I really stop and connect with what has touched me- I enter into a different state of mind and consider different ideas. I begin to see the world differently." Rosa further notes that the moment of resonance, in which the person feels fully alive and is the opposite of burnout, cannot be forced or coerced.

The notion of non-instrumental relations evokes many associations, most distinctively with German epistemologies. It brings to mind thoughts of Kant's "ding-an-sich" and the unknowability of transcendentals. It suggests a mode of intuition identified with romanticism, which Rosa partially affirms. I think of Martin Buber. Rosa, in this work, cites Buber in passing and the centrality that Buber places on relationships and the experiences that occur with the engagement of 'I" and "Thou." Rosa also brings to mind Erich Fromm (an associate of the Frankfurt School) who contrasted "having" with "being."

While the applications of resonance in this brief presentation are undeveloped, Ross, as a sociologist, asserts that his concept of resonance has transforming possibilities for society, politics, and the prevailing logic of frenetic growth that governs contemporary life.

The nature of resonance, as a moment of changed consciousness, opens the door to religion as a an ally – indeed a locus – where we can find values and narratives that alight with what resonance suggests. To be sure, Rosa is not naive to religion's gross failures to fulfill its most sublime objectives. He notes, "Historically speaking, hardly any other entity has been a more effective resonance killer than the Christian church."

Intrinsic to the religions themselves, Rosa notes that religious institutions, "...and especially those that are dogmatically concerned with preserving their 'pure teachings' – can therefore quickly become monsters that not only kill the vertical axis of resonance but also, in so doing, cause social relationships to fall silent..." The dogmatizing of pure teachings, Rosa concludes, leads to the amassing of social power under the guise of "merciless commandments, domination, and submission in the name of God." It is this propensity that can explain the rampant sexual abuse we have witnessed in the Catholic church and others, as well as in denial of an equal voice to women and exclusion of the LGBTQ+ community. Rosa's appreciation of religion is highly selective, which given religion's variety and complexity, it must be. Despite its gross shortcomings, he nevertheless sees something distinctive in religion that provides the gateway to resonance that he seeks. Pointing to the best in religion, he notes that the religions, "...possess elements that can remind us that there's another way of relating to the world, a way that is not growth oriented or intent on controlling things." It is not only religious teaching or inspiring Biblical verses that can open us to this other way, but churches themselves can still play this role. He cites the experience of entering a church, chapel, or temple. Not always, but sometimes, our disposition, our relationship to being in the world, changes. Our experience is different from being in an office or a supermarket. We move from a stance of agency to one of patiency. Control falls away and aggression has no target. Will such encounters engender the experiences of resonance? Not necessarily. But the stage has been set, and this possibility is critical to Rosa's analysis. As Rosa further notes, such openness to resonance can occur in other spaces. For those for whom religion has no appeal, resonance can emerge while standing at the ocean's shore or when walking through the woods.

Rosa contends that the yearning for resonance is a powerful human need, and concludes with the notion that "If society loses this sense, if it forgets that this type of relationship can exist, then it's ultimately done for."

But what of democracy? What of its relationship to religion? With the virulent divisions we currently experience, with the consequent absence of dialogue across lines of political difference, Rosa asserts that resonance is necessary. The fundamental requirement of democracy is that people listen to one another. He states, "Democracy needs a listening heart in order to function. It needs to be perceptive to (very) different ideas, and it needs to be transformed...religious traditions and institutions have at their disposal the narratives, cognitive reservoirs, rites, practices, and spaces in which a listening heart might be cultivated and experienced....We must allow ourselves to be invoked-spoken to - if democracy is to succeed... At the heart of modernity's crisis lies a crisis of invocability.

One senses that Hartmut Rosa is an academic who is on a mission. The endpoint he seeks, I would maintain, has a long history of its own. The transformation of consciousness that will lead to the transformation of society and the often unseen ills to which the masses of men and women are not fully aware. Yet, having defined those ills and the needed response, Rosa provides scant information as to how opening the space for resonance can be effectuated. Whom is he addressing and what are they to do – politicians, church leaders, academics, citizens in general, people in the pews? The critical questions of which persons and mechanisms will lead and participate in the process remain unanswered.

But, as noted, this is a very short work, and by necessity raises more questions than it can answer. That said, the ideas that Rosa presents are critically worthy of attention. At a time when democracy is severely threatened, and religion's most precious resources have been drowned by a celebration of its own power, Rosa turns our attention to what is most basic to both religion and democracy. By introducing us to his concept of resonance, Hartmut Rosa is reminding us of what lies at the basis of our humanity.

In these times, when ominous political realities have been compounded by pessimism, it is good to receive a message of hope. Hartmut Rosa is a humane scholar who pushes against conditions that govern our lives and the malaise that has darkened our social horizons with creativity and passion.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Cornerstone Press has just published William Luvaas's new short fiction collection, The Three Devils & Other

Stories. In these stories, the apocalypse comes to Southern California in a nearly-unrecognizable near future wherein severe climate change imperils the economy and social order and wreaks havoc in people’s personal lives. It’s a wild ride from the cruel streets of Los Angeles to the San Jacinto Mountains. The air itself becomes toxic, Los Angeles is mostly deserted, and predatory gangs wander the streets, along with dreaded “stalkers.”

To survive, people must do battle with those three devils that have long-plagued humans: fear, ignorance, and denial. While these are not light-hearted stories, what writer Frederick Bush said of Luvaas's novel Going Under also applies to The Three Devils: “Luvaas’s great power as a storyteller brings the reader up out of these sorrows and into a sense of redemption that is triumphant and true.”

Call it a work of Cli-Fi or speculative fiction, but one that follows its own rules.

Scientists are asking us to help them educate people about what we are facing—to bring it home to them, so to speak. This is what Luvaas is attempting to do in this collection, as he did in his 2013 collection: Ashes Rain Down: A story Cycle.

Paul Rabinowitz News

New poems, short stories and photographs:

(Fiction)

Stoneboat Literary Journal, "The Ending"

Barely South Review, "The Studio"

(Poems)

Stone Poetry Quarterly, "Tongue Tied"

Soup Can Magazine, "Nor'easter""(Photography)

Same Faces CollectiveAnd much more! See his webpabe at paulrabinowitz.com

SAD NEWS

Newspaper man and novelist, Norman Julian--chronicler of Mountaineer basketball, homesteader-- and friend of many, including me

Our friend and colleague Carter Seaton died 12-23-24. She was the author of many book,s including. See and obituary here. For a list of her books, which included novels and nonfiction about the back-to-

the-land movement, memoir and biography, see her website.

Hilton Obenzinger reports the death of Alan Senauke, who "practiced many things, notably Zen Buddhism as Abbot of the Berkeley Zen Center. But he was also a musician, an activist, a printing press operator, and a poet. I've known him since 1965 and collaborated on a lot of projects. "

See a memory piece about Alan at Shambala.com.

GOOD READING & READING IDEAS ONLINE

Check out Fay Martin's columns in which she bounces off her reading and thinking and offers insights for local communities in Ontario.

The latest issues of Danny Williams' "Adventues in the Written Word" is February 2025.

The new Issue of the Jewish Literary Journal

Here is a great reading list from Jeff Rudell. Jeff says he subscribesI "to a Substack 'book club' run by the author and teacher George Saunders....At the end of the year Prof. Saunders asked members to suggest their favourite reads from 2024. The resulting list [linked here] is a bit long (and so, perhaps less useful than a streamlined top-ten might be) but it has some wonderful selections."

Take a look at Joe Chuman's Individualism and Its Discontents on his Substack blog.

ESPECIALLY FOR WRITERS

Kelly Watt's newsletter continues to be compact and interesting. She directs us to a good blog post by Elizabeth Kaye Cook and Melanie Jennings about the Big Five and Literary Fiction.

Recommended Book on writing: Architecture of the Novel

Writer Beware (blog and website) have a lot of excellent information to make sure writers aren't scammed. They appear to be part of the excellent Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association,(founded in 1965), but are definitely aimed to be useful to writers of all genres.

BEST BOOKS LIST!

Shelley Ettinger's best books list from the past year plus. She says, "All fiction except the last. In no particular order."

Babel by R.F. Kuang

Lucky Boy by Shanthi Sekaran

Big Girl by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

When We Were Sisters by Fatimah Asghar

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang

Chain Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

The Future by Naomi Alderman

James by Percival Everett

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Blackouts by Justin Torres

Symptomatic by Danzy Senna

Behind You Is the Sea by Susan Muaddi Darraj

You Dreamed of Empires by Alvaro Enrigue Dixon

Descending by Karen Outen

Headshot by Rita Bullwinkel

The Canopy Keepers by Veronica Henry

Same Bed Different Dreams by Ed Park

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

The Delaney Bennetts by Desiree Kannell

Long Bright River by Liz Moore

Absolution by Alice McDermott

Happiness Falls by Angie KimAnd the only nonfiction one but it's a whopper: The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers #239Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

April 27, 2025

Octavia Butler, Yu Miri, Laura Tillman, Amor Towles

Shameless Self-promotion:

A very short story by MSW: "Recessional" just up at The Raven's Perch

A Blog to help writers with motivation "Karinwritesdangerously" features MSW on Sharing Stories

Contents

Book Reviews

Essay: Nonfiction: Men’s Reading by Christine Willis

Back Issues

Announcements

Things to Read/See/Listen to Online

Especially for Writers

Book Reviews

Unless otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

COVID19 Haiku by Wesley Bishop Reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Kindred by Octavia Butler

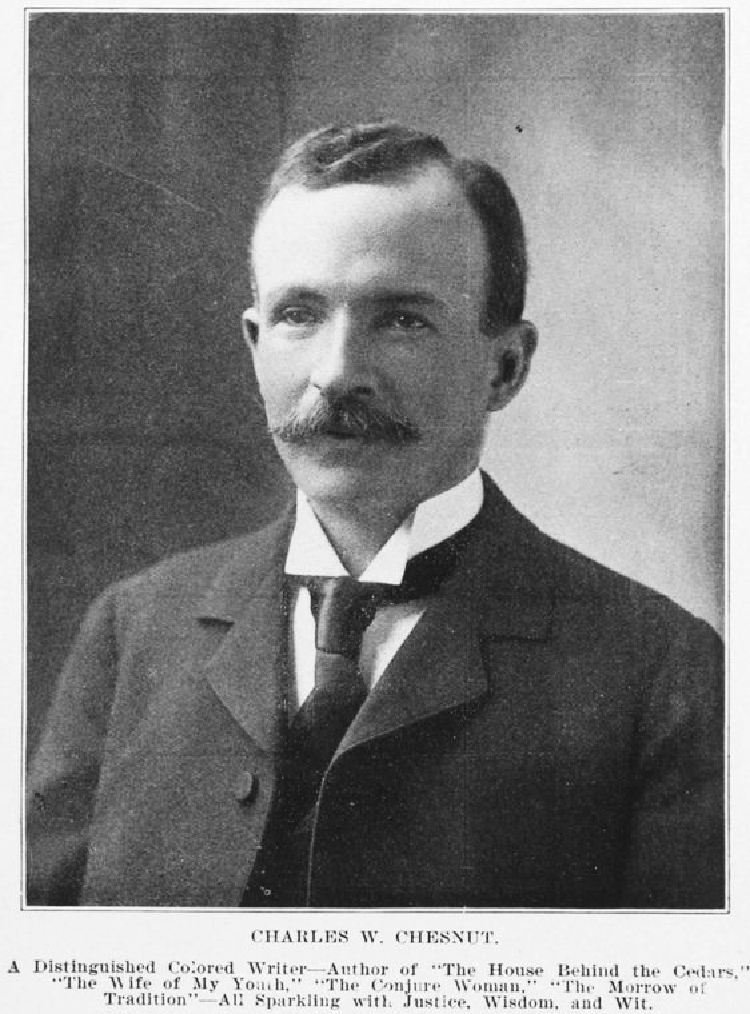

The Marrow of Tradition by Charles W. Chesnutt

The Girls by Emma Cline

Waiting for the Barbarians by J.M. Coetzee

Is Paris Burning? by Larry Collins & Dominique LaPierre Reviewed by Diane Simmons

Echo Park by Michael Connelly

The Waiting by Michael Connelly

Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly by Kenneth C. Davis

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides

We Carry Smoke & Paper by Melody Gee Reviewed by Diane Simmons

River and Stone anthology by the Morgantown Writers Group. Rviewed by Elena L. Perez

Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor

Fortune Favors the Dead by Stephen Spotswood

Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson Reviewed by Christine Willis

The Migrant Chef by Laura Tillman

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles

The American Claimant by Mark Twain Reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri

A friend told me she reads Books for Readers but thinks it is too long!

It is definitely long--but I never really imagined anyone reading every word! Rather, I picture people skimming over it, checking out the nice pictures I've borrowed off the Web, skimming a few things that look interestng--reading more fully what catches your fancy.

And, especially, finding an old book or a new independent one that you would never have discovered otherwise.

And speaking of short, I finally finished Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly by Kenneth C. Davis (see my review below). This issue has a couple of the last of the short novels recommended by Davis that I read. I also have some of the usual things I am rereading plus books I always meant to read and finally did. One of those is The Virgin Suicides (see review here). I also reread one of my all-time favorites, Octavia Butler's Kindred.

There are also TWO reviews in this issue by Edwina Pendarvis! as well as reviews by Elena L. Perez, Diane Simmons, and Christine Willis. Willis also gives us an interesting short essay just below that speculates about why she prefers reading nonfiction to .

Nonfiction: Men’s Reading by Christine Willis

I grew up with the vague notion that novel reading was not as valuable (maybe not as manly, male being the more valuable gender in the 1950’s and 1960’s) as reading non-fiction. I suspect that this attitude filtered down from Jane Austen’s era (and before) over the next 150 years (and might continue to exist in some form); while not everyone has been impacted by the attitude, some may feel a faint guilt reading fiction.

Concerning novel reading from Austen’s Northanger Abbey, 2013, Anchor Books, David Shapard’s annotated text: page 218:

“... But you never read novels, I dare say?” (Catherine speaking to Henry Tilney)

Henry: “Why not?”

Catherine: “Because they are not clever enough for you -- gentlemen read better books.”

(Page 219, Shapard’s Note #10):

“Catherine is expressing a common stereotype. Women were considered to be the main consumers of novels – regarded as inferior reading – and men the consumers of nonfiction genres such as history, religion, or classics, which were held in higher esteem. Records from libraries and reading societies do show a stronger female preference for fiction and a male preference for nonfiction, but they also show many men reading novels.”

My preference has been to read the (nonfiction) annotations in Shapard’s annotated Austen books while I am reading the text as the annotations are more interesting to me than the story itself and add to the depth of my understanding of the story, appreciation of the text, facts of Austen’s time of living, and how the facts might contribute to current life. I doubt that I would have read books of Austen’s beyond Pride and Prejudice without the annotations (which provide me with justification for reading fiction). But beyond the historical influence of the greater value of nonfiction, I prefer it because I come away from the experience of reading (of spending the time) having gained more than just entertainment, more than screen time on the printed page. I gain non-speculative ideas I can use as barter in an intellectual exchange with others.

There are those people (I among them) who don’t feel comfortable enjoying life: maybe these are the people who do not enjoy fiction, and their discomfort with fiction and entertainment is a better explanation of a preference for nonfiction

Reviews

River and Stone anthology by the Morgantown Writers Group. Rviewed by Elena L. Perez

The River and Stone anthology of short stories and poetry is a wonderful blend of voices from the Morgantown

Writers Group, which was until recently led by the late George Lies and is now continued by Melissa Reynolds and Patricia Patteson.

The book opens with a touching dedication to George by his daughter, Erica. I enjoyed reading this glimpse into their relationship; I met George only briefly in a few online writers group meetings, but anyone who mentioned him to me had nothing but good things to say. There is no doubt he was a very special person and a talented writer bursting with wisdom.

I was pleased to be able to read some of George’s own pieces throughout the anthology. My favorite was Potted Lilies, about a man who passes by an ex-girlfriend on a trip to town. He can’t remember her name so ticks through the alphabet hoping to jog his memory, which then becomes a running theme throughout the story as we learn more about his past relationship and his current one with another woman. George’s writings are definitely a standout of the collection.

There are so many wonderful pieces in this anthology that it’s tough to pick only a few to mention. Starting off the collection is a beautifully personal piece by Melissa Reynolds that’s filled with emotion and contemplation. It perfectly sets the tone of the anthology by examining the self in the present moment, yet also encompasses all the layers of past and future selves. It ends by leaving room for the reader to make their own interpretation, perhaps of their own life’s layers. I found myself reading it over several times to savor it.

Another piece I enjoyed was Fizzle by Alexandra Persad, which is a bittersweet story about a young couple falling in and then out of love. They connect over a shared passion for writing, symbolized by matching notebooks, and the story is told through snippets of video captured by a VHS camera. As a filmmaker and writer myself, I enjoyed this blending of the two genres, which created a nostalgic vibe, both for past eras and past loves.

I also enjoyed Loy Krathong by Jeremy Bock, which portrayed a family with small children enjoying the aforementioned Thai festival. The parents guide their children in making banana leaf baskets to float on the river, but woven among these interactions is dialogue between the two adults, hinting at larger socio-economic worries that the children don’t fully catch onto. The truthful interactions and dialogue provided an interesting slice-of-life

story.

Tea for Two by Aimee Hoffer is a fun steampunk, women empowerment piece. I was delighted at the introduction to Sharpe’s Tea Shoppe, where steam-powered coat racks greet visitors and mechanical iron Scottie dogs serve tea.

Budapest Lane by Matthew Smallwood has a quiet, contemplative vibe as two friends converse on a front porch. The Lake by Eric Casdorph also starts off quiet with lovely descriptions of the mist and lake, but gradually turns into something more sinister.

None So Blind–The Advent by Alan O’Connor and April Bird Walk by Elizabeth McConnell (the former flash fiction and the latter a poem) both chronicle time spent with patriarchs, learning to connect with nature. Physical Fitness and the Chipmunk Factor by Janis-Rozena Peri connects readers to nature in a different, rather absurdist way when the main character is recruited by local forest chipmunks to join a 5k race.

Cypher Basket by Emily Stanton is a lovely little science fiction piece about a pet robot. Fragments: The Language of Dreams by Cerid Jones is a hybrid of fiction and poetry, exploring one woman’s complicated approach to relationships. Built Like A Greek Temple 1837, a poem by Kellie Cole, lovingly describes the physical and historical attributes of a church built in Wheeling, West Virginia.

I was impressed with the wide variety of genres found in this anthology–including everything from memoir to speculative fiction to poetry to mystery to non-fiction–as well as the diverse locations, time periods, and array of characters. There really is a mix of something for every reader.

The length of each piece was just right: enough to get a taste of each world and feel invested in the characters and story, and sometimes leaving the reader curious and eager for more.

The collection as a whole was divided nicely into sections that complimented the works within.

The authors are equally impressive in their command of language. Vivid imagery and colorful characters fill the pages of this anthology, and as a Southern California native, I appreciated the range of perspectives set in West Virginia–and a few internationally–which provided me with a glimpse of the life and nature there. Reading this anthology was a journey into real and imagined worlds and I enjoyed the chance to be part of it.

Learn more about the Morgantown Writers Group at https://morgantownwriters.org/ and purchase the River and Stone anthology in print or e-book from Barnes & Noble or from Amazon.

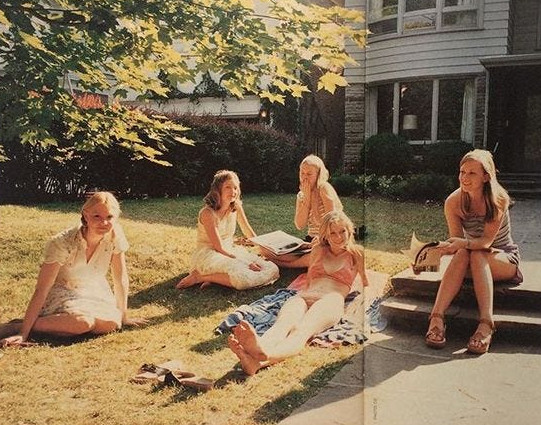

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey EugenidesThis is a book I've been hearing about for its full 25 years since publication. It seems to be one of those books that hits certain people of a certain age right between the eyes, and others of us not so much. It was just right for Emma Cline (coincidentally I reviewed her novel The Girls in this issue) when she wrote of it about it seven years ago in The New Yorker . Even if I wasn't the right audience for it, It stayed in my mind after I finished reading, and I think it informed some of my dreams for a night or two.

Eugenides writes about suburban Detroit just as that city was sliding out of middle class heaven. It's told nicely in the unified voice of a group of adolescent boys who are obsessed with the five Lisbon sisters. There is a lot of agglutinative listing of the accoutrements of the sisters' lives--their clothes, their games, their odors, their health and their make-up products. You know from the first page if not the title what is going to happen, and you watch it happen through the hungry gaze of those neighborhood boys.

I skimmed a few reviews and discussions that made a lot of the "male gaze," which is certainly part of what destroys the girls, but equally destructive is the overly strict parenting style of their mother and father. Eventually, the girls withdraw from school, from the community, from all the elements of everyday life. Their father leaves his job as a math teacher too, and eventually the house deteriorates with almost supernatural rapidity. The family stops having groceries delivered.

I kept wanting the story to include at least one of the girls just walking out on the horror, but you know quite clearly that this isn't going to happen. The book has a deep pessimism about the city, about adolescence, about girls, about the future. This is, of course, true to life about moments in all adolescents' lives and about far too many moments in the lives of adolescents who commit suicide. For me, at my much later stage of life, it all feels too determined, even pre-determined. As if Eugenides is punishing the Lisbon sisters.

At some level the whole thing feels like the fantasy of a bunch of teenage boys jacking off over some girls in a window. On the other hand, there is the splendor of it sentence by sentence.

Get a younger person's take on it: look at Cline's essay.

(Image above right is from the movie version).

The Migrant Chef by Laura Tillman

This is Laura Tillman's second book, well-received like her first, and widely reviewed. Her first one came out of reporting she did when living on the border between the US and Mexico about some murdered children. This one is part of an answer to the wildly over-simplified and brutal views of too many North Americans about migrants.

The book is about Eduardo "Lalo" Garcia Guzman who was a child laborer, a migrant, a felon and permanently barred from the US. He is also now a chef at the highest level, owning restaurants in Mexico and traveling around the world (except to the good old US of A). For good overviews of the book see Kirkus and The Guardian. The second one even comes with a recipe!

While Tillman's book definitely centers on the Migrant Chef, it also examines his family and the rise of celebrity chefs in Mexico. The book has a subtitle: "The Life and Times of Lalo Garcia," and that is probably my favorite part.

There are long, fascinating passages about Lalo's wife and her interactions with some of the upper class Mexicans with whom she, a middle class girl, went to private school. Lalo's mother gets a long section too. She, like Lalo, mourns his father who was the original migrant in the family, spending much of his life moving from Florida to Michigan, picking whatever was in season to be picked. These crews of migrant workers, without any path to citizenship here, led a brutal life, with damage done to adults and children not only by pesticides (and no one will probably ever know if that's what killed Lalo's dad and made Lalo sick) but also by stress leading to things like the destructive illnesses Lalo's mother suffered.

Still, it's a book with a happy ending--Lalo and his mother and his siblings are alive and living well--rich complex people whose lives belie what North Americans stereotype as "illegals."

A bonus is Tillman's descriptions of food that make you want to book a plane and a table.

TWO REVIEWS BY DIANE SIMMONS

Is Paris Burning? by Larry Collins & Dominique LaPierre Reviewed by Diane Simmons

(First published 1964)

Yes, I know that Boomers are mocked for being obsessed by WWII.

But—after a visit to Paris and then returning to our political climate at home—I decided to re-read Is Paris Burning?, the title said to be taken from a question Hitler sent to his officers who still held the city as the Allies approached.

Post-visit, I wanted to see what had happened in places I had just seen, such the small and tranquil square in front of Notre Dame, where, eighty years ago, a colossal tank battle took place. And, obviously, here in America, we are all required to renew our study of insane and vengeful leadership, something we post-war kids thought went out with the Nazis.

Though by late 1944 the war was pretty much lost for Germany, a weak and hate-filled Hitler ordered the Germans still holding Paris to mine it with explosives. Hitler—one pathetic little man-- would lose the war, but the world would lose Paris. In this telling, one German, General Dietrich Von Cholitz, dared to quietly and heroically refuse Hitler’s orders and, through various machinations, allowed the most beautiful city in the world fall relatively unscathed into the hands of the Allies.

I don’t think the book, originally published in French, broke new historical ground, but I did enjoy the moment-to-moment reporting of these thrilling days: the little girls in Alsatian costumes who offered flowers to De Gaulle (the great man noticed, barely); the Parisiennes who hurled themselves onto and into American tanks entering the city; the French soldiers racing to telephone booths, finally able to call their mothers after four years of war.

I also enjoyed going back to a time when the Americans were the good guys. May it come again.

We Carry Smoke & Paper by Melody Gee Reviewed by Diane SimmonsMelody Gee, a Chinese-American woman and author of this unusual collection of essays, was adopted from a Chinese mother in China by a childless Chinese immigrant couple in America.

The adoptive parents are loving, but Gee’s life is complicated and confusing, a quilt, as she writes, made up of secrecy, fear, endless labor, and the uncrackable code of English. Ultimately everything is about the struggle to survive. Anything that does not contribute to survival is a waste.

Gee knows that she is adopted, but this fact must remain a secret for reasons that aren’t clear. So many things aren’t clear.

One example is ritual: her parents, who have lived in America since their youth, seem not to comprehend Chinese ritual. Or perhaps it is considered vaguely unsafe. The girl is on her own to figure out what to believe in, which observances make sense, which don’t.

This confusion ultimately--as seen in the later essays—leads Gee to the Catholic faith. The church appeals in part because of its rituals. Though initially mysteriousness, they can be taught, learned and understood. The adult conversion process is a lengthy and complicated, and Gee is often frustrated. In the end, however, she finds herself on newly solid ground.