Books for Readers Archives #191-195

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 191

June 29, 2017

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Our friend, Lee Maynard,

the author of Crum, has died.A correspondent of Lee Maynard's, Christine Willis, writes to share Lee's response to her question about whether he had been raised in the Baptist Church. He said, "Baptist, yes. Southern, hard-shell. Narrow minded. Wild-eyed. Terrified of an angry God. (And those were the more liberal ones.) Raised? Hmmm, I can't really call it being 'raised.' More like -- kicking, screaming, pounding on the floor . . . (you get the point). I come from an entire family of church-goers, all except me. Have done a lot of probing and in the process have looked at a lot of religions, but not one of them seemed to be looking back."

Meredith Sue Willis's Books for Readers # 191

In This Issue of Books for Readers:

(If there's no byline to a review or comment , it's by MSW)

Phyllis Moore's list of Appalachian Young Adult literature

Unbroken Circle: Stories of Cultural Diversity in the South

A Space Apart

The Strawberry Moon by Victor Depta

Concepcion and the Baby Brokers by Deborah Clearman Revisited

The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith

Imperial Spain 1469-1716 by J.H. Elliott

Stories by Nathan Englander

The Fifth Season by N.M. Jemisin

On the Move by Oliver Sacks

Reader Reviews

Things to Read & Hear Online

Announcements and News

Irene Weinberger Books

NEW! YA BOOKS BY APPALACHIAN WRITERS!

Phyllis Moore has created a rich list of YA novels with Appalachian themes and/or Appalachian writers. She (and we) welcome suggestions and additions-- please email your ideas..

Personal Announcements:

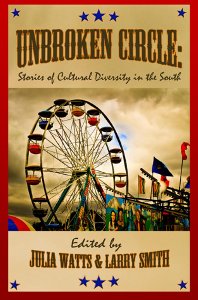

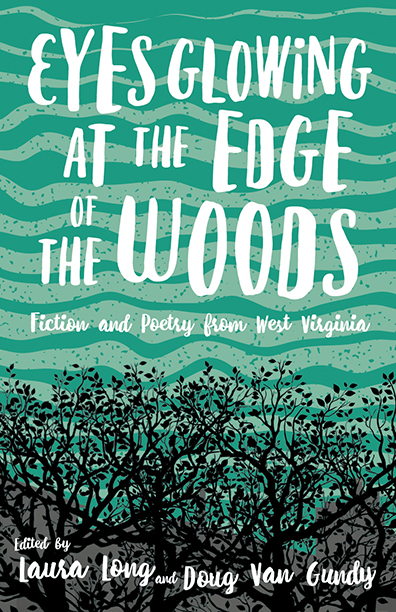

First, I'm proud to have a section of my upcoming novel in this anthology:

Unbroken Circle: Stories of Cultural Diversity in the South

In turbulent times, what we need is possibility, and in this rich gathering of diverse voices, Editors Julia Watts and Larry Smith give us just that. A girl molds clay against her deaf brother?s ears to heal him. A gay man finds his Appalachian clan in a dark world. These are stories and essays about the blues, about poverty, about families lost and made. Unbroken Circle is about broken and unbroken lives, and ultimately, hope. To purchase, try the usual online suspects or Bottom Dog Press directly. For more information about this book, contact: Larry Smith, lsmithdog@smithdocs.net, phone: 419-602-1556, fax: 419-616-3966, or go online to http://smithdocs.net.

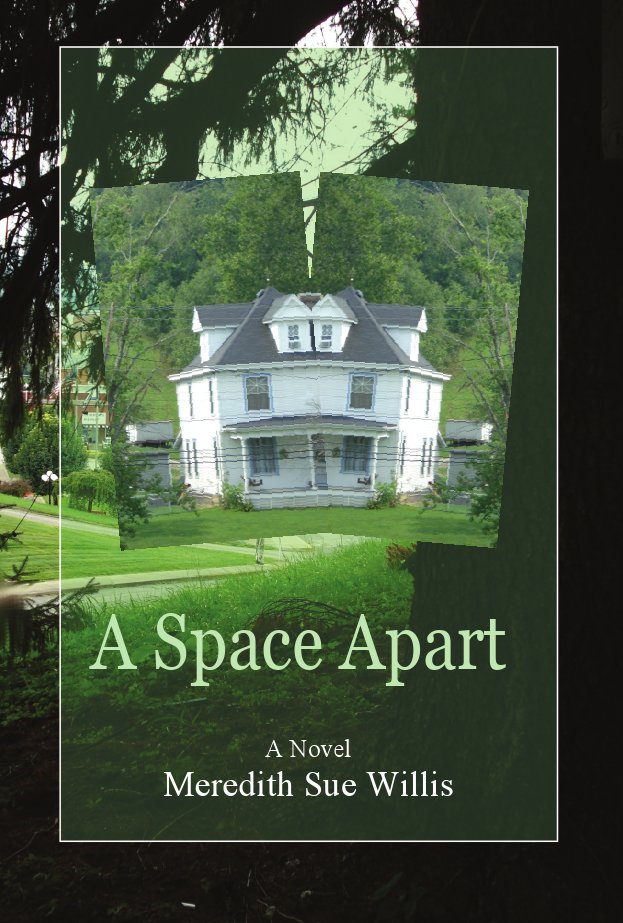

Second, my first novel has just come out in its revised hard copy edition from Irene Weinberger Books. The ebook of this revised edition is available from Foreverland Press. For a description of the new edition and reviews of both the first and current editions, click here.

For more from Irene Weinberger Books, click here.

Reviews

The Strawberry Moon by Victor Depta

Depta calls these poem/meditations "paragraphs," and they sit solid and quadrilinear

in the center of their white space--insights and explorations, speculating about samsara and nirvana and phenomena and noumena. They always come back to, and often start from, plants-- joepyeweed is a favorite -- or the weather. Depta is taking on a project similar to Emily Dickinson's fresh eyes attempting and sometimes succeeding in penetrating the meaning of existence. He mentions her once, in poem #63, and like Dickinson uses precision of natural observation to enter into a dialog with philosophy and religion (Buddhism, mostly, for Depta).

He has passages of refined humor as in "Dillweed," #58, which questions how one knows that another is truly enlightened: "Behavior is not a sign of enlightenment...And isn't there something suspect about an experience which is inexpressible? The same ineffability could be said about the odor of dill weed in my garden, pungent even in the street."

"The Praying Mantis," #61, is a relatively long piece that takes us through hot weather and a little bit of childhood, then the work of biologist and critic of religion, Richard Dawkins, then goes on to offer complex ideas about the soul, ending back at the praying mantis. Some of the pieces are short and surprising, others like the one just described, longer and more complex, but there is always a rhythm that eventually becomes musical, as if the poetic beat were not in syllables but in the whole of these "paragraphs,"

The final piece, "The Corn and Soybeans," has as the final words of the entire work, the statement "samsara and nirvana are one," which is at the heart of Depta's book.

Concepcion and the Baby Brokers by Deborah Clearman

In Issue #190, Ed Davis reviewed Deborah Clearman's Concepcion and the Baby Brokers. Now I have had the pleasure of reading it for myself. These linked stories, set in the town of Todos Santos like her novel Todos Santos built a careful and enticing world. The voices are totally convincing, and I especially enjoyed how affairs and pregnancies and lovers out of marriage have a generally positive, or at least neutral, effect on the community. In several cases, decisions are made to accept someone else's child as your own, or to marry someone you didn't think was the one you loved. In general, the bonds of the community are thereby tightened rather than destroyed.

I was also intrigued by the local class system with the "Mayans" and the "Ladinos" as well as the norteamericanos . One story takes place completely in the States, and that one, "The English Lesson," is very funny in its outsider's take on the language, plus what makes the student begin to get serious about studying it, plus-- again-- sex as a constructive, friendly act.

For a sample story, try "The Flor" in Green Hills Literary Lantern.

The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith

This is my first Highsmith novel (although of course I've seen some of the famous movies of her books, including Hitchcock's version of her Strangers on a Train). The Price of Salt is in many ways like a pulp Lesbian novel of the nineteen fifties, only raised to art. It is about a secret love affair and it has (spoiler alert!)

a happy ending. It was a best seller, published under the pseudonym "Claire Morgan" and republished 38 years later as Carol under Highsmith's own name. It came out as a movie starring Cate Blanchett in 2015.

The focus is on twenty-one year old Therese who is somewhat depressive, vaguely engaged to a man (but not a fan of sexual intercourse), and apparently a talented set designer. Looking for something-- a job, an understanding of why she doesn't love her lover– she takes a short term position at a department store like Bloomingdale's and has a love-at-first-sight experience with a beautiful, affluent matron, Carol. Therese make the first move by writing Carol a letter.

Carol clearly is attracted, but treats Therese semi-maternally when she invites her to stay over at her suburban New Jersey house. Carol has a mink, a maid, a best friend from earliest childhood, and a beloved daughter who is presently with her husband. They are in the process of divorcing, and this becomes important to the plot--whether Carol will get to keep the child or not.

Therese and Carol go on a long cross country drive, stopping at all sorts of upper Midwestern cities, where they drink and smoke and eventually begin a steamy physical relationship. The novel has a lovely noir quality that makes this kind of life feel glamorous, although I think I like even better the New York City-in-the-fifties parts. There is some melodrama at the end, but the struggle to take a child from her mother because of the mother's sexual orientation was very real. There is some ugly blackmailing of Carol to separate the daughter from her, and all heavy homophobia of the period. It's a dark narrow world, but gripping and convincing.

READER REVIEWS:

Dan Gover writes: "I just finished a great book--Minor Characters by Joyce Johnson. Best book about New York in the 1950s I've read in donkey's years: a free young woman coming out of a silent generation glomming on to the new Beat energy. After a middle class background and college on the Upper West Side, Joyce had a relationship with Jack Kerouac and hung out in the Village with the young writers, artists and low-lifes of the era. She walked the tightrope between love, wasted and survival. Jack called her Joycey; she was 21, he was 34; Allen, Memere, Lu Carr, Elise C, Hiram Haydn: the all there. Very gutsy stuff: absolute authenticity. Read it"

Phyllis Moore writes about Marc Harshman's new collection Believe What You Can: " I considered writing a review for this 88 paged collection and then discarded the idea, so to speak. My reason being that this review by MSW says all anyone need to know about this astonishing collection. It is an insightful review and an intriguing collection. The ability of this poet came as no surprise, he is the current poet laureate of West Virginia. What did surprise was the off-beat humor tucked in so many of the poems. The poems I enjoyed or pondered most: 'Postcard;' 'Aunt Helen;' 'Evidence;' 'Where No One Else Can Go;' 'Pink Ladies;' 'Vehicular;' 'It Was Told;' 'Jackson Pollock and the Starlings, Moundsville, West Virginia.'"

SHORT REVIEWS & BOOKS RECEIVED

There's a strong review of Diane Simmon's The Courtship of Eva Eldridge by Valerie Nieman on her blog . See the Books for Readers review here.

Yorker Keith's The Other La Bohème....

...is now available and receiving excellent reviews. Reviewers say things like "An engaging twist on a classic opera, lush with drama and romance in a contemporary setting" (Kirkus Review ); "A superb rendition of the classic adage that life imitates art (and vice versa); "If you would like to read a novel about a different kind of artistic world, full of the challenges that come to people when they chase their dreams, The Other La Bohème is second to none;" "Yorker Keith writes beautifully and those who love music, especially fans of La Bohème, will be smitten by this story as well as those who just enjoy the opera. ... The writing is elegant, flowing like music, and polished. The plot is well-paced and the conflict developed around the career and the love experiences of the characters helps to give the entire story a strong dynamic."

Also, note some good news about his previous novel!

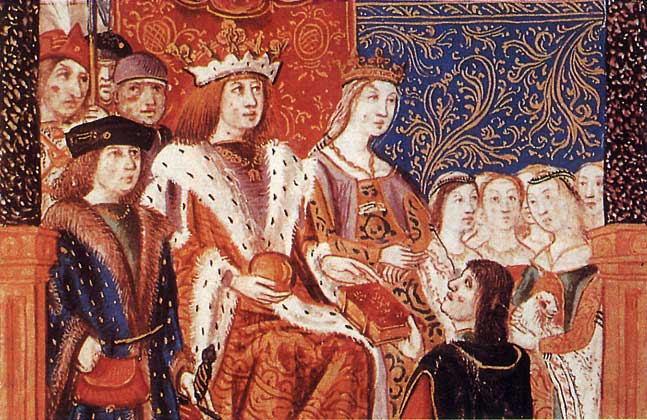

Imperial Spain 1469-1716 by J.H. Elliott

I have long been fascinated by the ugly, prognathous faces of the Hapsburgs that appear in so much 16th and 17th century art. This long, detailed history helped clarify their place in European history for me. First, I was surprised to find out that they are were descendents of los reyes catolicos, Ferdinand and Isabella, who Americans tend to associate only with Christopher Columbus. In fact, Columbus and his "discovery" were not by any means the most important thing to happen in 1492 in the eyes of people living then. Isabella and Ferdinand were much more interested in their struggle with the Muslims in southern Spain, and, of course, in how to combine their separate kingdoms into one.

The book probably has more information that you want or need, but I kept coming back to it. It begins with los reyes catolicos then their children and their son-in-law Charles V (the Holy Roman emperor). Much time is spent on the long reign of Phillip II (their grandson). He is the one who married Mary I of England and later launched the Spanish armada against Elizabeth I. This was the imperial high point of silver deliveries from the Americas and vast Spanish holdings. The dynasty ends at the beginning of the 18th century with Charles II, pathetic, possibly retarded, physically deformed, and owner of the most extreme "Hapsburg jaw" of all.

It's all about the rulers and pretenders and how they succeeded or failed. Pretty depressing, but I think I now know some of the players, even if I'll have to look back at the scorecard periodically.

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

I've been so enjoying the wonderful writing of the late great Octavia Butler, but she is so good that she makes me impatient

with the writing in other science fiction novels. This one took me a while to start enjoying, but I'm glad I gave it a chance. It seemed at first to have too many characters whose voices seemed too similar, but this turned out to be a trick with time. Stop reading if you don't want a spoiler. The various point of views turn out to belong to the same woman at different stages of her life. Nicely done--a surprise every time it happened, with some confusion of the type that makes you alert and interested and never gets in the way of story. I knew we were in different time periods, and I trusted it was all going to come together in some way.

Jemisin's world includes a race of stone people who move through the earth and human people who can take power out of the earth. There are repeated civilization-destroying catastrophes, sometimes natural, sometimes human caused. It is at moments reminiscent of being in Cormac McCarthy's The Road and in others like Harry Potter's Hogwarts.

And more books to come! Glad to have them to look forward to.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank: Stories by Nathan Englander

This was my first reading of Englander's work, and they are largely terrific stories-- just a handful of them, but deep and oh so carefully wrought. The title story is an honoring/imitating of Ray Carver in style and voice, but with an American Jewish couple and an Israeli couple facing off. It has a lot to say, amusingly and scathingly, about modern Jewish life. The last story, "Free Fruit for Young Widows," is probably the most ambitious and best, about Holocaust survivors and what it means to have empathy.

Note to teachers: Most of the stories are online and available for students and study.

Read The New York Times review here.

On the Move by Oliver Sacks

Sacks' memoir is to some extent a history of his writing life. He presents himself as more of a writer and humanist than a scientist-- a generalist who loves science and also loves helping people, and who follows his intellectual bliss.

It was a life full of friendships and relationships, but also interwoven with the deep sadness of many decades without sexual intimacy. He fell in love around the age of 76, then died of cancer five or six years later.

One of the oddest things to me was that Sacks says he was always "face blind," meaning he didn't recognized faces, but rather voices. He doesn't explore this in this memoir, but I wonder if that (isn't it a neurological deficit too?) might not be another connection between him and his various quirky-brained patients.

A solid and fascinating book, and now I want to read all of his work that I haven't yet.

A List of Appalachian YA novels from Phyllis Moore:

Here's something very exciting: Phyllis Moore has created a list of Coming of Age and Young Adult novels and memoirs set in, or written by, Appalachian Authors, with a strong focus on writers from West Virginia. Take a look: something different for your own reading or for students or young friends.

READ AND LISTEN ONLINE: THINGS NOT TO MISS

David Weinberger's "Alien Knowledge: When Machines Justify Knowledge." in BACKCHANNEL is an excellent explanation of difficult matters of how our computers now offer knowledge backed by processes we don't understand– and how this matches the real world.

Ed Davis's "The Publishing Workshop I Never Gave."

Joan Newburger's story "A Bad Day in the Promised Land" online at Persimmon Tree!

Podcast: link to an interview with Ingrid Hughes, author of Losing Aaron, on the The Kathryn Zox Show. The show is also available for download from The Kathryn Zox Show podcast page in iTunes

MSW interviews Helen Wan, author of The Partner Track.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, GOOD NEWS, CONTESTS, REMINDERS, AND MORE.

Yorker Keith's debut novel Remembrance of Blue Roses won the Pacific Book Award 2017 in the best fiction category. Also, see Yorker Keith's latest book The Other La Bohème.

Summer issue of Persimmon Tree!

The Montclair, NJ writers group has a new website-URL: http://montclairwritegroup.org/

Check out The Thick of Thin , Larry Smith's memoir from Bottom Dog Press.

New!

Appalachian Murders & Mysteries edited by James M. Gifford and Edwina Pendarvis

The first part of Serenity Paz's FBI romance series, Chronicles of Carlo is now available.

See Neva Bryant's poem here.

Jim Minick: writes: "Fire Is Your Water, my debut novel, has arrived in the world, AND it just received a starred review from Library Journal, which called it 'an outstanding first novel full of appealing characters and an inventive plot based on true events. This belongs at the top of every spring reading list.'"

If you want to catch Jim live, here are a few dates for summer 2017:

July 1 Midtown Scholar Bookstore, Harrisburg 1:00"Taking Out Fire: PA Dutch Folk Healing and Fire Is Your Water"

July 9-14 Radford U Highland Summer Conf Workshop July 11 RU's Highland Summer Conference Evening Reading 7:00

July 13, 7:00 July 28 Writer's Day, Abingdon, VA Highland's Fest. Workshops July 28 Writer's Day Reading, Heartwood, Abingdon, VA Reading 7:00

Aug 26 Reading, Avid Bookshop, Five Points Store, Athens, GA, 6:30

Aug 27 Reading, Southern Lit Alliance, Chattanooga, TN, 2:00

Sept.23 Berry Fleming Lit Fest, Augusta, GA

Oct 5 5-8, Midtown Market, Augusta, Signing w/ wine and food.

Oct 13-15 Southern Festival of Book

Nov 20 Grayson LandCare/Blue Ridge Nature Center, Independence, VA 7:00

And Don't forget these:

Llwewllyn McKernan's new book of poetry:

Writings in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 presidential election: Howl, 2016! Poems, Rants, and Essays on the Election, edited by Trish MacEnulty (Prism Light Press). Especially check out the piece by Carole Rosenthal--a strange and compelling story of being lost.

Suzanne McConnell's story "Neighbors" is going to be translated into Chinese and published in a Chinese literary magazine! Thanks to New Ohio Review's prize and

publication and the internet! And thanks to Ping Xu, Associate Prof. of Modern Languages at Baruch College for choosing it and doing the work of translating.

See an excellent article online by Jane Lazarre, "Where Do They Keep the White People?"

Spring Publications from Marsh Hawk Press.

Poem of the month from Barbara Crooker.

New: Marx by Fred Skolnik--an account of Marxist theory and modern capitalism.

Penner Publishing has more reprints of the novels of the late Monique Raphel High. (See our interview with Monique in issue, #185)

Don't forget The Courtship of Eva Eldridge by Diane Simmons--nonfiction about leaving the farm, women in war industry in the 1940-s, and serial bigamy! See review in Issue # 186.

Also from Irene Weinberger Books:

More from IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 192

August 23, 2017

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Meredith Sue Willis's Books for Readers # 192

In This Issue of Books for Readers:

(If there's no byline to a review or comment , it's by MSW)

Donna Meredith Reviews Appalachian Murders & Mysteries

edited by James M. Gifford and Edwina PendarvisJoel Weinberger on Middlemarch

Things to Read & Hear Online

Upcoming Books

Announcements and News

Irene Weinberger Books

I've spent late spring and most of the summer selling the house where we lived for thirty years, buying a new house, getting estimates from painters and asbestos removers, selling or throwing out a Sisyphean mound of possessions, including a couple of thousand books, and finally moving into the new house six minutes away. Everything everyone says about moving is true: it is stressful beyond belief and totally dominates your every waking moment. I wasn't hungry for a month, and found myself unable to read real literature. Adding to how deeply I sank into my very private business has been, I think, a despairing sense of powerlessness in the face of the insanity of the national leadership at the present time. How much easier to spend time contemplating which picture should go on which wall, shortening a cafe curtain, breaking down more boxes and tying them in bundles for recycling.

What I did read, I read strictly on my Kindle.. The physical books were still packed, so I borrowed genre e-books from the library, and finally reread a twentieth century classic. Here's what I read: (1) a memoir manuscript I was asked to blurb (doc file emailed to the Kindle); (2) three (or was it four?) Michael Connelly-Harry Bosch mysteries – a cop series recommended to me by another writer as competently written which I would agree to); and (3) To the Lighthouse.

The latter is something of a tradition for me. I re-read it periodically, and one of the times, if memory serves, was just after we moved into the house on Prospect Street thirty years ago. I remember sitting in a rocking chair near the big plate glass window in the living room, isolated by a lot of bare floor. This was before some kindly friend pointed out that the best way to deal with a big room is to put furniture in so-called conversational groupings rather than spread out. Duh.

So this time, when I finally felt that my brain could handle something besides straight narrative--when I began to get tired of Harry Bosch's male angst given

moral loftiness by his devotion to justice, I turned to language in the service of exploring the meaning of time and place. To the Lighthouse has been just right. It even centers on a house, especially the middle section called "Time Passes," which dramatizes the effects of weather and human neglect on an empty house as years pass, and the family doesn't come back.

Woolf is so brilliant in this book: she details a multitude of people's world views, the colors and sounds of their highly developed perceptions-- and then tosses out major deaths among our favorite characters in brief bracketed sentences. The summer house, which had been given its life by the life force of Mrs. Ramsay, is an appropriate symbol, natural because it is the family's own symbol. Then of course, in the third part, t, they do come back, their numbers thinned, and finish some business left hanging in the wonderful, long first part: Lily Briscoe's painting and, of course, the sail to the lighthouse.

One of the great wonders of the book is the extreme realism of how it captures change over time. When I first read the book, in college or shortly after, I remember skimming it and panicking because I thought I didn't understand it. At that period of my life, I thought everything was a puzzle and a test, and that it was my job to gather my intellectual powers and figure it out and pass the test. I expect I tried to read the book too fast, to get the point, not yet grasping that for some books, the point is the experience, not the answer to any question.

The odd thing is that my brain was sharper then, but reading To the Lighthouse now is far easier. It will never

be a fast read-- it doesn't have narrative momentum the way Harry Bosch's adventures do, dragging you in and on-- but in the right mood, which I was in as we emptied boxes, it is like stepping into water on a hot day, surprising and refreshing, an adventure and a relaxation as you lean back and float. Perhaps it is a book for grown-ups, as Woolf famously said about Middlemarch, "the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels for grown-up people."

One more note: technically, Woolf does the omniscient viewpoint possibly better than anyone in modern times. She was only one generation after the magisterial Victorians. She skims from consciousness to consciousness with aplomb. Her own ego, of course, was clinically fragile, so perhaps that plays into her ability to hear and convey many voices. We also can't forget that she writes about people whose interests and education are very similar to each other's and hers-- they all share a frame of reference, cultural norms, and even speech patterns. Is that what omniscience in novels needs to succeed? Also, she has good structural elements supporting the book: Mrs. Ramsay herself, of course, often the object of others' attention when she herself is not the consciousness, and the powerful objective correlatives of the lighthouse and Lily Briscoe's painting at the beginning and end.

Anyhow, it's sad and sweet and brilliant and captures the whispers of time passing like nothing else. So good to be reading again.

(Image above right is Virginia Woolf's mother, Julia Jackson Duckworth Stephen, the model for Mrs. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse.)

Historical looks at selected murders in Appalachia, 1809-2012: Donna Meredith Reviews Appalachian Murders & Mysteries edited by James M. Gifford and Edwina Pendarvis

True crime stories sometimes evoke such a strong sense of revulsion and nausea I have to put the book aside, but not so Appalachian Murders & Mysteries, compiled and edited by James M. Gifford and Edwina Pendarvis.

This thoughtful collection provides a thoroughly researched history of murders in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Southern Ohio, rather than a blood-drenched rendition aimed at inducing visceral reactions. The 17 authors of the 23 stories have varied backgrounds. They include scholars, journalists, a state representative, teacher, historians, a judge, an archivist, a publisher, and an administrative assistant.

Accounts are presented in chronological order, beginning with the murder of a black slave child by her owners in 1809 and ending with the murder of a 16-year-old girl viciously stabbed by her best friends in 2012.

In “The Murder of a Child Named Hannah,” by Phyllis Wilson Moore, it is hardly surprising that a slave’s owners could not be found guilty of murder; but it is surprising that abuse rose to such heinous levels that the community protested. Witnesses had seen the child hanging, suspended by a rope or chain, completely naked from a peach tree. The body was exhumed and the case of this tortured thirteen year old went to court. The farmer insisted slaves were not human. Under Virginia law at the time, he was legally correct. Morally, neighbors in Brooke County felt nothing could justify the child’s burns, cuts, and beatings. The county, which later became part of West Virginia, is one of the few in the United States where white residents took other whites to court over a slave’s murder.

The gallows narrative of James Lane is the subject of “A Public End to a Life of Crime,” by Edwina Pendarvis. These narratives, according to Pendarvis, were popular from the late eighteenth into the late nineteenth century. They were sold as broadsheets or pulp paperbacks, with the purported aim of turning others away from crime. During the Age of Yellow Journalism, these narratives provided lurid descriptions to titillate readers.

Multiple murders are the subject of several pieces, including “The Ashland Tragedy,” by Keven McQueen; “Feud Murders in Rowan County,” by Terry Diamond; “In Harm’s Way,” by Phyllis Wilson Moore; “Sunday Slaughter—Pike County, Kentucky,” by Edwina Pendarvis; “Together Forever: The Skyline Drive Murders of Don & Brenda Howard,” by Judith F. Kidwell; “A Parade of Horribles: The WVU Coed Murders,” by Geoffrey Cameron Fuller. I was familiar with the Harry Power murder farm described by Moore because the murder of widows and children took place near my hometown in West Virginia, but I was surprised by Diamond’s account of the feud murders in Kentucky. The feud, which lasted from 1884-1887, was even more brutal than the famous Hatfield and McCoy feud, which I knew about even as a child. This Kentucky feud accounted for 20 deaths and 16 wounded. It grew out of corrupt state and local government following the Reconstruction Era. The spark that ignited the Rowan County War happened on election day over a hotly contested race for sheriff.

A few pieces cover unsolved cases, such as “The mystery of the Injured Babies,” by Judge Lewis D. Nicholls, Retired. This piece delves into “shaken baby syndrome,” with neuroscientists questioning the idea that simply shaking a baby could cause death. Interestingly, many juries still side against the science, perhaps wanting someone to blame to the loss of life.

Another piece that caught my attention was “Charles Manson’s Ties to the Tri-State Area,” by James M. Gifford. Before reading this account, I only associated Manson with Hollywood. Yet he had strong ties to Ashland and Boyd County in northeastern Kentucky and to Charleston, West Virginia. It wasn’t surprising to learn Manson, a sociopath, spent his youth in near constant trouble, bouncing from one form of incarceration to another.

Appalachian Murders & Mysteries adds to our understanding of the crime of murder, providing historical perspective. Fortunately for all of us, murder is rare—and that rarity contributes to our interest in it. As Pendarvis points out in the “Afterword,” the murder rate in the Appalachian region covered in this volume is even lower than the national average.

The authors try to lay out the reasons behind each of these criminal acts, but this collection leaves us pondering that unanswerable question: how could anyone deliberately commit such an irrevocable act against a fellow human?

Joel Weinberger on Middlemarch

Middlemarch is a book of surprising breadth, given its rather specific setting. Through 4 or 5 plot lines, depending on how you count them, it covers a society and era that I haven't seen too many novels attempt. Furthermore, it's not as simple a story as it initially appears to be, and even the plots take turns you don't expect. The novel explores social norms, feminism (of a limited, 19th century sort), politics, wealth, and a host of other topics.

All of that having been said, I just often found myself bored while reading Middlemarch. It is wordy, it is drawn out, and while the plot has some gripping moments, they are far and few between. And so here I find myself, enjoying enough of it that I want to like it more than I do, but I would be hard pressed to convince myself to read it again.

Ultimately Eliot is always compared to Austen, which is hardly fair. Middlemarch is, in fact, a vastly more ambitious book, and not too directly about its own plot. It is about the world the characters inhabit and their society. Having said that, if the comparison must be made, it does feel like it drags compared to, say, Pride & Prejudice, and while the ambition is admirable, I couldn't find myself drawn into it in the way that so many others seem to be.

YA BOOKS BY APPALACHIAN WRITERS!

Phyllis Moore has created a rich list of YA novels with Appalachian themes and/or Appalachian writers. She (and we) welcome suggestions and additions-- please email your ideas..

READ AND LISTEN ONLINE: THINGS NOT TO MISS

Try a couple of these stories online by the late, great Grace Paley: "Wants" "Goodbye and Good Luck" "Mother"

For teachers of writing and others: an excellent piece from Teachers & Writers on travel writing.

Check out this article about what novels can do--and maybe can't anymore.

An excellent obituary of Lee Maynard.

The New Yorker's farewell to Michiko Kakutani as she retires from The New York Times.

Ed Davis Blog post on writers and depression.

The New York Times ' "20 Years of L.G.B.T.Q. Lit: a time line". Many books you know, many for your to-read list.

Read David Weinberger's review of Shakespeare & Company's production of Cymbeline.

UPCOMING BOOKS

Jane Lazarre's new memoir The Communist and the Communist's Daughter

is coming this fall. You can start reading the prologue right now!

Lori Brown Mirabal's book about becoming an opera singer--and teacher--Coming soon!

Hilton Obenzinger's latest: Treyf Pesach--to be reviewed soon.

Coming soon from Mountain State Press, an anthology titled: Voices on Unity: Coming Together, Falling Apart. Thirty three talented contributors are featured in the collection with their wonderful essays, poems, fiction, and song.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, UPCOMING BOOKS, GOOD NEWS, AND MORE.

Joan Newburger's story "A Bad Day in the Promised Land," published in the Winter 2017 issue of Persimmon

Tree, has been selected for a "2017 Write Well Award" and will appear in the next Write Well Award Anthology. The purpose of the anthology is to "recognize authors of some of the best stories on the web" and to raise funds for Silver Pen, Inc. a non-profit organization that helps writers by offering online courses, etc.

More good news about Yorker Keith's The Other La Bohème: The novel about four opera singers is featured in the August 15, 2017, issue of Kirkus Review Magazine in an article called "Chasing Musical Dreams" that highlights three books whose theme is music (page 224 of the issue)

Joseph Harms has a new collection called _Bel_ coming from Expat Press .

From Irene Weinberger Books:

More from IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 193

October 12, 2017

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Meredith Sue Willis's Books for Readers # 193

In Memoriam:

Thomas E. Douglass, who wrote

on Appalachian literature and writers, andHalvard Johnson, poet and co-founder

of Hamilton Stone Editions and The Hamilton Stone Review

In This Issue of Books for Readers:

(Reviews by MSW unless otherwise noted)

Thrust by Ken Champion

Joe by Larry Brown

Medusa's Country by Larissa Shmailo

Treyf Pesach by Hilton Obenzinger

Answering Fire by John Wheatcroft

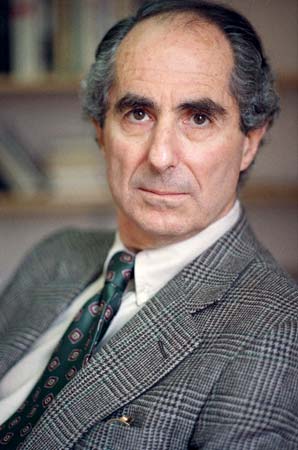

I Married a Communist by Philip Roth

The Tipping Point by Malcom Gladwell

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

Carole Rosenthal s on George Saunders

Phyllis Moore on Lee Maynard's last book

Young Adult Appalachian literature list from Phyllis Wilson Moore

Things to Read & Hear Online

New and Upcoming Books

Announcements and News

Irene Weinberger Books

There has recently been, as most readers know, a generally shuttering of print newspapers, particularly their book reviewing departments. Not replacing them, but cropping up like a vast field of mushrooms (some amazingly delicious and some likely to cause nausea) have been the short evaluations you find on Amazon.com and Goodreads as well as many other places. One of my reasons for writing this newsletter has been to share my own reading, in my own way, and to make a space for those of you who might want to share reviews here-- Please contribute!

Meanwhile, for myself, I continue to reread books by favorite authors. Sometimes I get lists from group reviews in places like The New York Review of Books or online aggregators like Literary Hub. I also get a lot of books to blurb, review, or evaluate for university presses; but maybe most of all I get ideas word-of-mouth from my friends and students. Some of my friends also blog. Shelley Ettinger's Read Write Red features her excellent taste in literature as well as her strong left-wing world view, and NancyKay Shapiro's Books Make a Life is a new blog, and one of the sources she recommends is Backlisted Podcast.

The book I want to talk about first here comes directly from a face-to-face conversation with Alice Robinson-Gilman, a serious and constant reader. She recommended a book called Joe by Larry Brown of Oxford, Mississippi (yes, that Oxford, MS). It is a book that she says she keeps re-reading, and that in itself made me very curious. The genre is

Southern Gothic, which usually involves a lot of drinking and violence and eccentric, often down-and-out characters. An article in Publisher's Weekly a couple of years back lists what it considers the quintessential examples of Southern Gothic, and they include Child of God by Cormac McCarthy (when he was Southern not Western), Twilight by William Gay, and Faulkner's Sanctuary. Larry Brown shows up in the article, but not as one of the top ten. The genre isn't my favorite, as it has always seemed a little exploitative to me: Southern Gothic writers have a tendency to go slumming and play at poverty. I'm sure they have suffered in their lives as we all have, but they have also had for at least a while, access to a room of their own and a publisher. So I was skeptical when I started Joe, but I ended up liking it a lot. Brown's book has plenty of the requisite violence and grotesquery, but it feels earned.

The novel is mostly a study of the eponymous character Joe, although large sections follow the life of an illiterate boy named Gary from an astonishingly dysfunctional family headed by a Faulknerian Old Man named Wade Snopes-- sorry, I mean Wade Jones. About the only enormity Wade doesn't perform on his children is to have sex with them, at least not on stage in this book. But that's probably because by this time in his life he appears to have drunk himself into impotence.

Meanwhile, Joe lives a far more affluent life than the Wades. He runs a crew of tree poisoners for a lumber corporation, which then hires him to plant pine trees to replace the dead trees. He has a house, buys a fancy truck in the course of the novel, has an ample supply of whiskey and a cooler in the truck full of beer. He also has a divorced wife, children, and a grandchild. People like him, women of course, but also a local store keeper and the sheriff.

On the other hand, he is clearly on a downhill roll. He repeatedly gets in trouble with the local cops and engages in a blood feud with another local good old boy. Through the novel, Joe's deterioration gains momentum, and the events increase in violence-- Old Man Wade as well as Joe is revealed as more and more evil. There is a general blow up at the end, with a kind of self-sacrifice from Joe. This all feels believably inevitable. The hard-working but preternaturally ignorant young Gary does does appear to have a little luck, though, because Wade, though he unfortunately lives, leaves Gary. Interestingly, Brown chooses to write an epilogue about the natural world. It feels like the right way to end this-- the closest, maybe, that Brown can come to a happy ending.

More Books

Thrust , Ken Champion's latest novel, follows three men, two of whom are largely loners, with many similarities of style, but completely different world views, particularly in politics and architecture. Piero is a renowned and increasingly wealthy international architect of post modern sensibilities and a conviction that his art takes precedence over everything else. Liam dabbles in various kinds of work but is mostly a sort of modern day flâneur– a stroller, a café denizen, a walker in the city-- London, in his case. He, like Piero, is highly sensitive to buildings and light and skylines, and part of the pleasure of this novel is the observations of both men.

The third man, Jim, has fewer point-of-view

sections and is a skilled bricklayer who has a relationship with the bricks he works with that is analogous to the architectural sensibilities of the other two. Jim, though, has a wife and at least one deep friendship, and is a touchstone for the novel. Champion's work always finds groundedness in people who work with their hands. Jim's work is part of what allows him a real friendship and a wife.

The other two have difficulty sustaining long relationships, although Piero has an engineering colleague who follows him around the world and Liam, slowly over the course of the novel, has a growing relationship with Mary. I think Liam's real love, though, is London, which he takes into his pores as he walks and observes, loving the evidence of the past as well as London's polyglot present.

The three stories make their way in parallel narratives that one trusts will eventually braid together, and the expectation is nicely fulfilled. Jim's Polish co-worker dies in a work accident that is partly related to post-modern architecture, if not directly to one of Piero's buildings. Piero comes finally to London where he is unexpectedly jolted out of his life of jet-setting and art by bad deeds from the past. Liam grows most: both in his developing love relationship and also in taking on some political activism in speaking out against the razing of old churches and other structures. Finally, Liam and Piero meet face to face and have a long dialogue about building and society. Characteristically of Champion, the plot climax– while certainly exciting– takes second place to the conflict about building and razing and the question of what is progress.

It is a solid novel, determined to take its proper time using its own proper materials. The writing draws you in and the threads have an inevitable satisfying tying up into a final knot that stays in your memory and imagination.

Medusa's Country is more stunning poems from Larissa Shmailo. She is endlessly surprising, riffing off other literature-- an erasure poem using lines from "The Lotus Eaters" section in Joyce's Ulysses; one called "My Vronsky" with

reference to Nabokov's failure to understand Anna Karenina-- but also about a relationship destructive to the narrator. There is with short lines and hard-hitting rhymes like Sylvia Plath's famous "Daddy." Shmailo's Daddy, however seems to have hidden his love in strange places:

I looked for it in boxers;

In the dumps of ten detoxes;

In the roll of rundown rockers;

In anal & banal boys.

There is, of course, a lot more here, as in her previous books, we have passages of her personal story of living on the edge and in the lower depths as in the "The Trick Wants to Go to Plato's," the old Plato's Retreat sex club where single men aren't allowed. The narrator, who is indeed in the sex business, says " I sign a document attesting that I am not a prostitute; my whore name is Nora."

These poems alternate with ones using myth and rhyming patterns and parody (See "Fragment from the Ilatease of Homey, from a Recently Discovered Mycenaean Test." The final poem of the book, the title poem, about Medusa, ends

But once a man stood like a statue

Before my cave of trees

His eyes transfixed by my serpents

That hardened, froze, and pleased.

You will never be bored by Larissa Shmailo's poetry. I don't suppose that sounds like much of a recommendation to read it, but what I want to say is that her inventiveness and wit are only matched by her searing life experiences and her observation of death.

She surprises over and over.

I thought I was going to have the curmudgeonly pleasure of saying negative things about the highly popular Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, and this one, to my taste,

started badly, but improved a lot. Gone Girl was a big hit when it came out in 2012. It is Flynn's third novel. Only three, too. She's been busy having a life as a journalist for Entertainment Weekly, getting married, having kids, etc.

Anyhow, I started out not believing in Nick as a man, really disliking Amy in her "diary" entries. It's efficiently written, and somewhere towards the middle when it is finally revealed that Amy is a psycho manipulator, I began to get really engaged. I went another third of the book interested in how Flynn was going to play this--interested in the plot but totally not caring about the people. I had seen at least part of the movie version and vaguely remembered some of the redneck resort part.

In the final section when Amy's voice began to come on strong, and I finally believed in Nick at least, and started to realize that is is probably a dark comedy. There are no real stakes--the main characters, who I didn't care about anyhow, were going to live (one minor character is murdered, but it's someone you feel like killing yourself).

It is a comedy in the technical sense too-- a wedding at the end, in this case the rejoining of the already-married young couple. I was pleased by Flynn's cleverness, and I think I get the book's success, but doubt I'd read anything else by Flynn.

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell started as a long essay or monograph, a staff article of The New Yorker. Like many nonfiction pieces that began in this form and then became a book, it has a ton of brilliant stuff early on that makes me want to think and discuss and read more– and then peters out and repeat itself and uses weaker examples in the effort to grow book-sized.

Nor does everything ring true to me--for example Gladwell's conviction that the Broken Windows theory of crime control was the real–and he appears to argue only-- reason crime dropped in NYC. He always writes well, of course, all enthusiasm and flashes of insight, but the book doesn't have the texture that the best nonfiction does (I'm thinking of The Murder of Helen Jewett about the death of a prostitute in nineteenth century New York). Gladwell himself says of his work, "You're of necessity simplifying....If you're in the business of translating ideas in the academic realm to a general audience, you have to simplify … If my books appear to a reader to be oversimplified, then you shouldn't read them: you're not the audience!"

Read more in the Guardian.

Hilton Obenzinger's new book of poetry, Treyf Pesach, has been praised by Paul Auster, Michael Lally, and Diane di Prima among others. It is mostly occasional pieces-- poems for a revised Haggadah, secular prayers, and psalms for the months since Mr. Trump became president. Obenzinger does his prophesying in long lines that are alternately outraged and humorous as he comments on politics and human follies over the last ten or fifteen years. Some of the poems are as up to date as "Dear Mr.. Donald Trump," one of 12 Psalms that end the book and says, "Due to a world that you cannot make into your own image/Due to shoddy real estate deals in the guts of refugees/We have to let you go/You're fired."

He typically uses everyday language in the classic American style of the New York poets and William Carlos Williams and, of course, the progenitor himself, Walt Whitman. Some of the poems have an incantatory quality and are meant to be read aloud, and indeed many have been performed. One of my favorites is a poem that was performed with a jazz ensemble that is called "Peace Comes to the World" and is full of delightful, zany imagined changes:

Politics becomes a way to meet new people and make sense

of the world, a kind of dating service and Department of

Public Works rolled into one.The suicide bomber walks into the marketplace, yanks the

string. Candies shoot our in all directions. He's become a

suicide piñata, except he forgets to die in the explosion of

sweets.Excerpts, of course, don't do justice to this kind of poetry that creates its efffects through long sentence-lines and heaps of images. A wonderful shorter poem called "Remembering/2011" is about how easy it is to be confused by how much you wanted something to happen in history: "Didn't Al Gore refer to that speech in his own inaugural ten/ years ago? I can't quite recall." And a sweet, very long 2014 poem called "Goodbye Books" is a valediction and farewell to a long list of favorite books: "The books line up and I shake the hand of each and every /one of them."

Charming and political, ranting and rough-edged, it's a book to read to yourself, or read aloud to others, or to use as a substitute for the religious texts you have rejected.

But feel free to laugh.

Answering Fire by John Wheat croft is a small book consisting of a short story and a novella, centering on the World War II experiences of a young sailor. The short story "Kamikaze," is wonderfully dark: we experience with the teen-aged protagonist some of the daily life of a big air craft carrier that is under constant threat from the Japanese suicide planes. The tension and horror of that are bad enough, but there is a possibly hallucinatory story line about another sailor, repeated described as silent, animal-like, and unintelligent, who hates their noncommissioned officer and gradually draws the protagonist into a mutual crime that is a deep look at the secret dark side of the human soul. It's an intense little piece, and a perfect mood-setter for the longer story.

"Answering Fire" is about an aging, highly civilized and thoughtful protagonist, who may be the young man from the first story fifty years later, on holiday in England with his wife. He is thrown back in memory by an encounter with another vacationer, a teacher from Japan. He begins to remember his experiences when the American naval forces, who had been told like the rest of America, that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki had saved the U.S. forces from a devastating resistance if they invaded Japan. Instead, the sailors, even far away from the nuclear devastation, find flattened cities and people living in holes, trading any saved valuables for cigarettes. This is an unusual and excellent book about what even that so-called righteous war did to combatants and victors as well as to victims.

I Married a Communist by Philip Roth is usually described as a roman à clef about Roth's marriage to Claire Bloom, but I pretty much missed all of that, and just read it as a Roth novel. I love many of the characters, especially the ones Roth loves (one of whom is not Nathan Zuckerman the protagonist). It's hard not to feel for the spectacularly flawed "Iron Zinn," and even more the older brother, Nathan's teacher, who as a ninety year old narrates most of the story. The background is wonderfully detailed, especially the romance of communism for a brainy Jewish kid growing up in Newark, NJ at the end of the thirties and during WWII. We get a lot of the black list and McCarthyism of course, and it goes on too long in places. I like how Roth gets excited about various crafts (glove making in American Pastoral, taxidermy and rock collecting here), but he probably uses more of his research than the novel requires.

I don't know if this is prime Roth, but second rate Roth is better than nine tenths of the books you read. Read and enjoy, Iron Inn and Murray the Teach and even tremulously manly Nathan Z., as they try to figure out America..

Still More Books!

Carole Rosenthal read George Saunders' Lincoln in the Bardo and liked it a lot. She says, "Saunders is very appealing to me, straight-eyed but deeply humane and often both moving and hilarious. One of the few white male biggies to depict working-class in a sympathetic way--although he can be and is viciously satirical. The collage he creates in Lincoln in the Bardo is very effective and an interesting way of seeing the USA--not completely dissimilar from Dos Passos many years before, but much more strange. Ghosts, or spirits anyway."

Phyllis Moore says that Lee Maynard's final novel, A Triumph of the Spirit, "proved to be another emotional high octane ride....the Jesse or Jesse-type guy gets pretty down and dirty in this new book. There are daring deeds: fights to near death, lots of women with beautiful body parts, wrecked motorcylces. It will repulse the spinsters and shock the mild-mannered. Queen Victoria would read it in secret. Just Maynard being Maynard If you are a Maynard fan, you will recognize pieces from his other books. They fit. He found a fitting way to wrap up his adventures and bid us goodbye."

READ AND LISTEN ONLINE

Joan Newburger's story "A Bad Day in the Promised Land," published in the spring 2017 issue of PersimmonTree, has been selected for a "2017 Write Well Award." The Write Well Award Anthology has just been published. The purpose of the anthology is to "recognize authors of some of the best stories on the web" and to raise funds for Silver Pen, Inc. a non-profit organization that helps writers by offering online courses, etc.

The Kirkus Fall Preview 2017 is online here with lots of good reviews, but especially look for one on Khary White's first novel, Passage.

Paris Review on John Gardener on the 35th anniversary of his death.

Excellent short short story by Beejay Silcox

Look for columns by Dolly Withrow in The State Journal on everything from Capitalism to Cats!

I'm still encouraging readers who don't know her to try a couple of online short stories by the late, great Grace Paley: "Wants" "Goodbye and Good Luck" "Mother"

Also, don't forget John Birch's blog reprinting pieces from his long career as a journalist and feature writer.

Teachers & Writers online magazine continues to publish wonderful, practical articles about teaching the arts to children, but often as in this one exploring the political with middle grade students, the audience should be as wide as possible. Take a look!

Tips for writing good fantasy.

How much should you pay (or charge?) for various types of editing services? Here's a list of typical ranges.

A lovely piece about a mother a son, and religion from The New York Times's "Modern Love."

A father's care for his troubled son: Ingrid Blaufarb Hughes' blog "Not the Whole Person"

And for something completely different-- a short story by the excellent science fiction writer N.K. Jemison. It plays nicely with time by dividing into out-of-order "chapters," and gives the old style satisfaction of a surprise ending: "Henosis."

Check out this article about what novels can do--and maybe can't anymore.

An excellent obituary of Lee Maynard.

The fall 2017 issue of the Innisfree Poetry Journal, is now available with a look a the work Pattiann Rogers.

Ginsko 19 is now online.

ANNOUNCEMENTS, UPCOMING BOOKS, GOOD NEWS, AND MORE.

Don't forget Blair Mountain Press--they do what Amazon.com can't, including providing signed copies, inscriptions upon request, a means of supporting your local post office, etc. etc. Their catalog will be sent on request, and their website is www.blairmtp.net.

Chany G. Rosengarten's new novel now available! "...a tale of Yerushalayim of the recent past, when families struggled to put bread on the table and children grew up before their parents’ plans for the future had a chance to unfold. In a story spanning decades and continents, a family struggles with the trials of facing the unknown and conquering their fears, as they hold on fervently to the promise of Jerusalem."

Jeff Biggers forthcoming book, The Trials of a Scold: The Incredible True Story of Writer Anne Royall. Years in the making, Trials chronicles the wild life and times of America's first female muckraker, Anne Royall, who was convicted as a "common scold" in 1829 in one of the most bizarre trials in Washington, DC. In praise of the book, Dorothy Allison calls Royall "a role model for those of us living in the age of Trump." For more info, check out the starred review in Publisher's Weekly.

One free entry to TCK Publishing's Readers' Choice awards for self-published/indie books.

More good news about Yorker Keith's The Other La Bohème: The novel about four opera singers is featured in the August 15, 2017, issue of Kirkus Review Magazine in an article called "Chasing Musical Dreams" that highlights three books whose theme is music (page 224 of the issue)

Joseph Harms has a new collection called _Bel_ coming from Expat Press .

YA BOOKS BY APPALACHIAN WRITERS!

Phyllis Moore has created a rich list of YA novels with Appalachian themes and/or Appalachian writers. She (and we) welcome suggestions and additions-- please e-mail your ideas..

From Irene Weinberger Books:

More from IRENE WEINBERGER BOOKS:

NEW AND UPCOMING BOOKS

By Jane Lazarre, Lori Brown Mirabal and an anthology from Mountain State Press:

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 194

December 11, 2017

When possible, read this newsletter online in its permanent location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

.

Meredith Sue Willis's Books for Readers # 194

In Memoriam:

Thomas E. Douglass, who wrote

on Appalachian literature and writers, andHalvard Johnson, poet and cofounder

of Hamilton Stone Editions and The Hamilton Stone Review

In This Issue of Books for Readers:

Special Request: Can anyone read Chinese?

Reviews

(By MSW unless otherwise noted)The Book of Norman by Allan Appel

Don't Mind Me I Just Died

The Communist and the Communist's Daughter: A Memoir by Jane Lazarre

New Children's Picture Books from Belinda Anderson

Short Takes on:

Rosemary: the Hidden Kennedy Daughter

Biography of Hannah Arendt

Phyllis Moore on Lee Maynard's last novel

World War I and the Visual Arts

Shelley Ettinger on Rivers Solomon's An Unkindness of Ghosts

Fay by Larry BrownNew Anthology from Mountain State Press

Links for Writers

Correction from Issue #193

Notes on Madison Smartt Bell and Nathan Bedford Forrest

by Phyllis Moore and Gerald SwickThings to Read & Hear Online

Announcements and News

Irene Weinberger Books

It's holiday season, and I'm asking everyone to think about giving books as gifts--

books from independent bookstores (see clickable logo right for a store near you) and small presses. If you are looking for books for young children, don't miss Belinda Anderson's list of good new children's picture books in this issue.

Some of my favorite small presses that have published my work at some point, in anthologies or in book form, include Montemayor Press, West Virginia University Press, Ohio University Press, Bottom Dog Press, and the small nonprofit Mountain State Press which has a brand new anthology out, Voices on Unity: Coming Together, Falling Apart.

There are tons of excellent small presses, and they are publishing some of the most interesting work by contemporary writers. One place to get an idea of the variety is at Newpages.com where you can survey the riches to your heart's content. Two presses I am involved with on the editorial side are Hamilton Stone Editions and Irene Weinberger Books. Surprise your gift recipients!

Here are some new anthologies from small presses:

A few reviews of recent small press/university press books:

The Book of Norman by Allan Appel

I love the concept of this book: an inveterate gambler dies and his two sons, one a rabbinical seminary drop-out, the other a near-convert to Mormonism, battle for his soul. It's a comedy, but a comedy with lots of Biblical and other research behind it. For example, you meet various types of Jewish angels and learn about the colorful cosmology and afterlife of Mormonism.

The narrator is young Norman Gould, and the time is 1967, with a background of the Vietnam War and anti-war protests and the Watts riots. Norman is aware of these things, but more engrossed in his homecoming to

Los Angeles where he gorges on enormous amounts of treyf foods while working as a counsellor in a Jewish day camp,alongside his brother who wants him, Norman, to break it to their mother that he is about to become a Mormon. Norman, of course, is hiding from his family that he has dropped out of seminary.

The struggle between the brothers is painful and funny, and Norman is desperate for meaning, constantly berating himself for a lifetime of achievement within the framework of Jewish religious training that he now feels was a fraud.

The family includes the deceased father who died with cards in his hand, and their mother who kept the family together by working double shifts as a waitress in a Jewish pastrami palace. There is a grandmother, too, the father's mother, who lives with them and is lovingly cared for in her old age, speaking almost only Yiddish except for some baseball terms she uses to interact with her grandsons. You end the novel with a lot of affection for all these people--including the mother's new boyfriend, the despised temple fund-raiser the boys call "the Foot." Everyone in this novel– unusual in modern American fiction– is morally a little better at the end than they are at the beginning. Norman says Kaddish for his father three times a day, deep and heartfelt, and stops gaining weight on pork chops and cheeseburgers.

The book too, maybe even more unusually in contemporary novels, ends even better than it began. The first two thirds are probably too hard on Norman, who is, after all, young and confused and high on his newly-abstaining brother's stash of wine-soaked joints. The ending isn't about returning to old beliefs (Norman's brother really does leave Judaism and goes on to become a Mormon in good standing and start a nice Mormon family). It's more about learning to love your brother in spite of his meshuga religion– and loving your mother who marries someone you never liked.

Meanwhile, the gorgeous Israeli maybe-angels do some magic before heading off to their next assignment, either fighting in the desert or saving more Jewish souls. More importantly to me, though, is that while their prowess may be truly angelic or may only be Norman's dope-dreamy exaggerations, it isn't really necessary to the beginning of wisdom and the acceptance of the mysteries of our universe.

Don't Mind Me, I Just Died by Caroline Sutton

The heart of this book of essays is several pieces about the author's mother dying, but surrounding them are many other wonderful stories at once revealing and reticent, quiet but with plenty of color and event. They tell of the suicide of a young

friend's boyfriend; seventies road trips; tennis; and the lives and deaths of beloved dogs. Sutton's father relates his harrowing war stories with an objectivity that creates as much amazement as the experiences themselves.

One of my favorites is called "Left Unhung," which is a wonderful tour of nineteenth and twentieth century paintings in a museum, one after another, with their meanings explored, what they meant to the narrator as a child, what they mean to her now. Has anyone ever been this honest about the experience of being in a museum? We're usually too busy trying to view the art in the correct way, or to sound smart, even to ourselves.

Sutton's mother is mentioned in various contexts, and bit by bit we begin to circle around a rich portrait of her living as well as her dying (which she does as so many of us do and will, in a nursing home). In a typical indirect but moving association, Sutton gives an echo of the mother in the little dog Pokie who appears first just as a part of the mother's life, then gets his own story at the end.

It is an organically organized and deeply intelligent collection that brings you close to a world of love and delight--and quiet suffering. Things are sometimes told obliquely, but always with inspiring grace and intensity.

Jane Lazarre's The Communist and the Communist's Daughter: A Memoir

Born in Kishinev, famous for pogroms at the beginning of the twentieth century, Jane Lazarre's father Bill and his immediate family emigrated to the United States when he was a teenager. He learned English with great speed, worked, joined the Communist Party, did a stint in prison, and always read widely, but especially Marx, Lenin, Dostoevsky, Theodore Dreiser and other masterful critics of the status quo.

In fact, Bill Lazarre's reading list, and what he and his daughters read together and discussed, is one of the threads that binds the book together. For this is a memoir about people who constantly think and discuss, and feel as passionately as they think.

As a young man, Bill went to Spain with the International Brigades to fight fascism, and this remained one of the high points of his life. His life in the Party back in the United States was also rich: he wrote and spoke publicly and taught, but the heroic days were gradually undermined by intra-party struggles as well as rumors that justice was not being meted out in the Soviet Union. He was eventually thrown out of the party for reasons associated with the last days of Stalin when any disagreement was tantamount to betrayal. The ideology he had built his life around for its clear path to a better world no longer seemed to work.

After losing his Party positions, he had trouble finding work that would support him and his two daughters. Harassed by the FBI and eventually taken before the HUAC committee, he stood firm and revealed nothing to implicate his old comrades, in spite of a real danger of deportation, even though he was an American citizen.

In his final years, he found some satisfaction in a quiet life, a worker hired by former comrades, reading all the papers, finding a second love. He also had a little time with his first grand-child, Jane's oldest son whose heritage is half Eastern European Jewish radicalism and half southern African-American. This becomes part of Bill Lazarre's hope for the future--for a time when international union will be the human race.

The author, meanwhile, as she grew up--and this is almost as much her story as his--turned to psychoanalysis and literature as a language for finding meaning in the complexities of life.

Telling these things about this book, of course, give no hint of its texture: it attempts and largely succeeds in creating a nuanced view of Bill Lazarre's emotional and political experience and the world he lived and suffered in, which was also the world the author grew up in. He has his heroic days recruiting workers for the righteous cause, and he has personal catastrophes when both his adored wife and then a second love die of virulent breast cancer. The author creates his life using his letters and notes, stories told and books written by his old comrades, and she also imagines scenes of him as a boy in Kishinev and alone in his apartment at the end of his life.

She also writes about what it was like to be a Communist Child, when the families gathered in living rooms over food and discussion, with the children loved by all the adults-- a hint, perhaps of the yearned for Utopia of equality and camaraderie.

The book is organized in generally chronological sections, but within those sections, it works by association, by retelling dreams, by including transcripts of and commentary on court proceedings. It is a collection of materials, insights, incidents, and imagery formed into a brilliant whole by Jane Lazarre's skill and patience.

It ought to be a classic of twentieth century American life.

Belinda Anderson Recommends Picture Books for Children.

Picture books make wonderful presents. The ingredient all of my picks have in common is that they’re fun – lessons and insights are bonuses. The following books were all new additions this year at my local library:

When a picture book begins with images of a sheep bathing in a tub, then blow-drying her wool, you know you’re dealing with an image-conscious ewe. But you also know what happens when shearing season arrives. “Now you’ll feel nice and cool,” says the herd’s sheep dog, who also doubles as the flock’s barber. Lola is very unhappy with the results – at first. But she learns that change can bring something new and good in The Sheep Who Hatched an Egg, engagingly written and illustrated by Gemma Merino.

The Bake Shop Ghost is a fun romp with a bit of mystery. It was written by Jacqueline K. Ogburn and ghostily illustrated in swirling colors by Marjorie Priceman. Both author and artist are avowed cake eaters.

The 20th Century Children’s Book Treasury is just that – more than 300 pages from 44 classic picture books and stories, selected by Janet Schulman. The selections include Madeline, The Snowy Day, Make Way for Ducklings, The Cat Club, Amelia Bedelia, The Story of Ferdinand and Miss Nelson is Missing! The stories are accompanied by reproductions of the original illustrations.

The young narrator of the picture book Still Stuck, by Shinsuke Yoshitake, is having one of those days. He decides he can take his shirt off by himself. He gets stuck and starts imagining what would happen if he was stuck forever. He thinks about asking his mom for help, then decides maybe it would be a good idea to try taking his pants off first. How many of us have thought, bad idea, five seconds after doing something that makes bad go to worse? Fortunately, Mom intervenes.

Breaking News: Bear Alert, by David Biedrzycki, is a hilarious picture book romp with bears who have been awakened early from hibernation and head downtown.

Author Matt Lamothe has come up with a picture book showing kids around the world at school and home in This is How We Do It: One Day in the Lives of Seven Kids from around the World. The large-format picture book follows the lives of seven real families throughout the day. In Italy, their breakfast is toast with Nutella spread, a cup of egg yolks mixed with sugar and milk, and tea. In Peru, the family has fried rice with chicken and peppers, sliced boiled plantains, and hot milk.

I truly enjoyed these books myself and highly recommend them.

Briefly Noted & Books Received (notes by MSW if not otherwise noted)

Phyllis Moore says of Lee Maynard's final novel, "A Triumph of the Spirit arrived in my mail (thank you Amazon) and it proved to be another emotional high octane ride. If you are a Maynard fan, you will recognize pieces from his other books. They fit. He found a fitting way to wrap up his adventures and bid us goodbye."

Shelley Ettinger recommends Rivers Solomon's An Unkindness of Ghosts. She rated it 5 stars on Good Reads and added, "More like a 4.5 but I'm rounding up because there's so much to love about this novel. I liked it a lot, and there was a lot about it I loved. In my endless, endlessly frustrating search for truly fine literature that can be categorized as SF, it's cause for celebration when such a rarity arrives. Rivers Solomon is a writer to watch, that much is clear. Can't wait for their next book." (From Goodreads)

I read Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter by Kate Clifford Larson as an ebook borrowed from the library. Rosemary, of course, was the Kennedy who was developmentally disabled. The lobotomy part was just awful, and the Kennedies were pretty awful themselves in a lot ways. Still, you can't read this and not understand the public fascination with them.

Rosemary, although always slow at reading and school, was also well-loved, carefully protected, and--judging from the photos--very attractive. She was even presented to the Queen of England, although family members conspired to keep her from being in conversations with strangers very long. In other words, she had a life, but was apparently as she got older sometimes angry and hard to handle.

So Papa Joe decided she needed her frontal lobe snipped, and she she ended up with physical disabilities and far less mental ability than she started with. Grim story.

Had she been the child of a poor family, would her story have had an even worse outcome? Or perhaps better?

Hannah Arendt: A life in Dark Times by Anne Heller was very satisfying to me. I've read a little Arendt, mostly essays in The New York Review of Books and lots of references to her, but I'd never known much about her--about her relationship with Martin Heidegger, about the brouhaha over Eichmann in Jerusalem, or about her in and out relationship with Israel and Zionism. Short book, very informative.

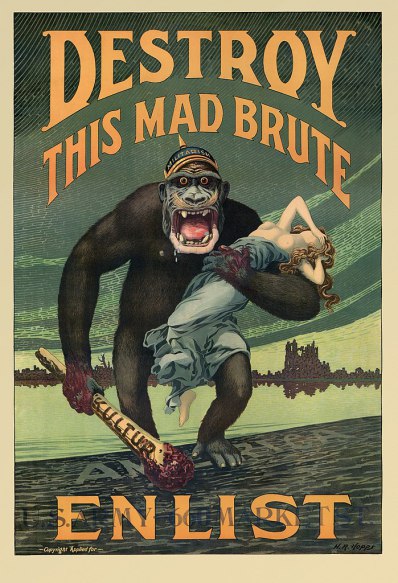

World War I and the Visual Arts by Jennifer Farrell is an issue of the Metropolitan Museum bulletin about art in Europe during the First World War. There are some propaganda posters (see the top of this newsletter), some examples of artists expressing patriotism from both sides--all just as the war began. Some of the artists actually went to war and were horrified, and many of them turned to anti-war art.

There are wonderful images by artists like Grosz, Beckmann, and Kollwitz, but also artists you don't usually associate with war imagery like Singer and Hartley and Marsden, even Bonnard.

I I admired Larry Brown's Joe a lot (see Issue # 193), but Fay seems wrong-headed to me in many ways. Some of it is excellent: Brown is a writer who can pretty much do exactly what he wants to do. He uses a flat affect and Raymond Carver declarative sentences that have a nice rhythm, and he knows a lot about certain parts of the worlds and certain kinds of places and people, and knows how to bring them to life.

The fault for me is two-fold: first, he tends to use killing people with guns as a substitute for plot development. There is a sort of elementary school trick of ending threads of story and characters with "And then they all died." Preferably by explosion,

The other fault is Fay herself, who is interesting in the early part when she is running away and a complete innocent with no ID (I kept worrying about that) barely able to read, not knowing how to use a pay phone or a dozen other things. In that part, her vast ignorance and vulnerability build incredible tension. She barely gets away from a crowd of nasties in a filthy trailer without being raped. So she's a survivor, and that works. Even when she does her first killing. I was reading eagerly to see what would happen.

But in the end, Fay becomes more the object than the subject of the story. When he did go inside Fay, Brown felt to me like he was slumming inside the little hillbilly Lolita. She becomes a temptress, and men end up dead.

The main focus turns to the the men around her. There's Sam, a good hearted fortyish cop who falls in love with her and tries to protect her, and there's the wildly off kilter and just-this-side-of sociopathic Aaron, who in his own twisted way also falls in love with her.

The final section is a drilling down, the three main characters coming together for an explosion, which Brown delivers, and I didn't really believe, although I couldn't stop reading till it was over.

I seem to be going through Anthony Trollope's Barchester novels again--it is, after all, Victorian novel season when the storm windows move into place, and the chill winds blow. This one is Barchester # 4: Framley Parsonage. Not my favorite of the series, but it improves as it goes along. It has, like Trollope's Phineas Finn novels, a lot too much elaborate playfulness about standing for parliament and parliamentary antics and the political parties, which he calls the Gods and the Giants.

The women are the best characters. Lucy Robards is small and "brown," but wins Lord Lufton's heart in spite of having no money. In many ways, even more interesting is Lord Lufton's mama, who is peremptory and conservative but also needs to be loved, and is able to change her mind.

I haven't mentioned the putative hero, Reverend Mark, who I don't like much. He is Lucy's big brother, and he gets caught up on a worldly path that ends him up in dire financial straits, He chooses to suffer passively, and is of course saved by his friends. Oh, and I like the feckless MP who borrows money from everyone he meets, and his sister, who loves only him. So maybe it's one of my favorite Barchester novels after all.

Eragon by Christopher Paolini is a popular dragon fantasy recommended to me long ago, and I finally took a read. It was written by the still-adolescent home-schooled Paolini, published by his parents, then picked up by a big press. It is lots of fun, bull of the energy and angst of youth. The hero Eragon is a somewhat inchoately angry and suffering teen-- well, he has some reasons: most of the people loves get killed or separated from him. Just the same he unnecessarily opposes people who want to help him. Lots of adventures and dragon and dwarf and elf-lore.

It was fun, but probably one in the series is enough for me.

Correction from Alice Robinson-Gilman

Alice Robinson-Gilman writes about my review of Larry Brown's Joe in Issue # 193 : "I think you mixed up something I said about my favorite books which I've read more than once. I liked Joe for giving me an insight (right or wrong) about the South but I've only read it once and don't intend to read it again. My few-more-than-once favorites are The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien, The Lake in the Woods by Tim O'Brien, The Fifth Child by Doris Lessing, and The Dangerous Husband by Jane Shapiro."

Readers, what novels or other books do you re-read? For me it's the Victorians. -- MSW

FOR WRITERS

Actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt talks about a new project and collaborative writing.

Some Notes on Confederate Nathan Bedford Forrest and Madison Smartt Bell

Phyllis Wilson Moore wrote: "Years ago I read a Madison Smartt Bell novel, ALL SOULS" RISING and liked it enough to then listen to it. The reader was perfect. Like Lee Maynard, Bell shows what is happening and you get that "yowser" feeling. Last week the library had his novels THE DEVIL'S DREAM on the sale table. I needed a car audio. And so ................. It is a Civil War story featuring Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. He was influential in the Klan's star -up and there is a statue of him in Nashville (My friend Gerald's current home town.) I've always disliked even the idea of him: slave owner, no Robert E. Lee. He was more like a cursing rough-cob edition of Stonewall Jackson with a slave mistress, too much adrenalin, and no fear.

"I'm not far into the audio but may have to go get the book as I want to"hear" faster than the audio. It is, so far, fascinating and even humorous, with some Lee Maynard women and style. If you have ever wondering why an upper class woman might marry a rough and ready guy, Bell shows why and uses only a few sentences. And they are rather humorous.

"Gerald Swick and I have discussed Nathan and his statue and so I am sending him this mail also. I may never get my car radio fixes as I am enjoying books on tape way too much."

Gerald Swick responded: "Last Friday evening I was in Columbia, TN, with a couple of friends and we passed a building just off the square that once was the finest hotel in town. I told them about the day one of Nathan Bedford Forrest's subordinates got into an argument with him in that building, pulled a pistol and shot him.

"'You SOB,' Forrest reportedly roared at him, 'you've killed me.' Whereupon Forrest pulled a knife and stabbed the guy, who fled the hotel, staggered to the square and collapsed in an alley.