Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers #216

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

September 1, 2021

MSW at NYU in Fall 2021--by Zoom!

Wednesdays, September 22- December 1, 2021:

MSW teaches Novel Writing WRIT1-CE9355001 at NYU online

6:30 p.m. to 8:50 p.m.Saturday November 13, 2021:

One day class Jump Start Your Novel WRIT2-CS9002

at NYU by Zoom, 1:00 p.m. to 5:10 p.m.

Rajia Hassib, Joel Peckham, David Sprintzen

Contents

Book Reviews

Announcements--Things Happening!

Genre Selections

Readers Respond

Things to Read Online

Irene Weinberger Books

Reading Lists

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue # 216Reviews are alphabetical by author, not reviewer.

If not otherwise noted, reviews are written by MSW.

More Michael Connelly

The Last Coyote

Trunk Music

Angels Flight

Forest Mage (Soldier Son trilogy book 2) Robin Hobb

A Pure Heart: A Novel by Rajia Hassib Reviewed by Marc Harshman

American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson,

the Woman Who Defied the Puritans by Eve LaPlanteBone Music by Joel Peckham

Melitte by Fatima Shaik

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 by James Shapiro

Critique of Western Philosophy and Social Theory by David Sprintzen

Reviewed by Joe ChumanFellowship of the Ring (first book of Lord of the Rings) by J. R. R. Tolkien

BOOK REVIEWS

I have been writing this online review for more than twenty years. My first, very short issue was in December, 2000. In an effort to take a little of the means of production into my own hands, I decided to become a small-time gate keeper in the reading and writing business.. After having been published by a couple of the largest publishing houses in the country, I had come to realize that the kind of work I did was not making enough money for the publishers to keep publishing me. I was rarely keeping a single publisher for more than one book.

At the same times, the books I was reading were almost never brand-new or best sellers. I was learning

something of how the economics of book publishing was changing, as were people's reading habits. I joined with some other writers and poets to reprint our out-of-print books (Hamilton Stone Editions), and eventually we published some new books too. We started an online literary magazine,

The Hamilton Stone Review. It felt to me like the right time to share my notes on my reading. I never expected a large subscription list, although it has grown to nearly 1,000 people. Many of them, of course, as with all Web publishing, never open the e-mail ("click through") or go to the site to read.

I like being one of a multitude of places you can get ideas for your reading besides The New York Times Book Review. Outlets for print reviews have become very few, and as time went on, people I knew personally or professionally would occasionally offer, or be prevailed upon, to write reviews.

This issue has a couple of those reviews by others. I am honored to have a review of the excellent A Pure Heart by Rajia Hassib written by the Poet Laureate of West Virginia, Marc Harshman (Woman in Red Anorak, winner of the Blue Lynx Prize).

I also have a review of David Sprintzen's work of philosophy Critique of Western Philosophy and Social Theory written by Joe Chuman, leader emeritus of the Bergen, New Jersey, Ethical Culture Society and professor of Human Rights at Columbia University. This is a substantial piece about a book that touches on ideas that seem important to me, particularly that "Individualism is a species of reductionism, which is the fallacious paring down of complex realities into a single phenomenon or explanation." For me, who grew up on cowboy movies and the American myth of the lone hero standing against evil (High Noon to the tune of Tex Ritter's "Do not forsake me oh my darlin'!"), it has been a slow journey to understanding how intertwined we are with the world around us. Chuman focuses on Sprintzen's reasons for why this mythology is part of what is endangering our species.

The other reviews here come from my usual hodgepodge of joyous reading: a searing collection of poems by Joel Peckham; speedy reads amd fantasy (including The Lord of the Rings); the wonderful life-and-times book, The Year of Lear by James Shapiro.

Also, I serendipitously (that would be a Daily Special on Kindle books) came across a 2004 book called American Jezebel about Anne Hutchinson, the great seventeenth century Puritan who saw by an inward light and challenged the Puritan system. She was actually a young girl living in London in 1606 and might well have passed Shakespeare himself on the street--although her family would never have gone to his plays! Their idea of entertainment was long sermons and discussions of evidence that they had been predestined to Heaven.

American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans by Eve LaPlante

Eve LaPlante's book about Anne Hutchinson is scrupulously based on historical research. Hutchinson's own words were never published except in in the transcripts of her trials before the civil and religious authorities, and her actions were recorded largely through the writings of her sworn enemies, particularly John Winthrop, the Puritan governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The complexities are many, and fascinating: underlying what happened to her are the minute but passionately held differences between different flavors of Puritans, who were themselves in religious struggles with the Church of England and multiple separatist and splinter groups, not to mention the Roman Catholics.

The Puritans crossed the ocean not for religious freedom (unlike the Separatists who landed, so they say, on Plymouth Rock) but to create a city on a hill, run by rigorously religious laws. And they wanted everyone to follow their exact ideology and beliefs. Anne Hutchinson saw herself as a Puritan in good standing and could argue Bible theology, but she also based many of her beliefs on her own inner life. She had confidence in her own thinking, understanding of the Bible, and her revelations from God. Winthrop and the others did not like this, and they also didn't like what they considered her un-womanly behavior. They did not want women speaking in public, not even to teach in small circles in her own parlors.

Hutchinson came from England as a full adult with her always-supportive husband Will and many children (she had at least sixteen pregnancies, most resulting in live births and children who got old enough to die by plague or murder. She came following her favorite preacher, and once in the colony, at the age of 43, she began teaching in small groups to women, and then to men as well.

Whether or not she was a precursor of feminism is an issue of great interest to many. Whether she was really a proponent of freedom of conscience is a little clearer: she, like Roger Williams, who was also run out of Massachusetts, eventually went to what became Rhode Island, which was founded on the idea of being a place for those who disagreed with received religious wisdom.

In any case, she is a fascinating character whose strength of leadership and ability to teach, and her belief in the inner light of the individual made her a hated opponent of the establishment. She also opposed wars against the native inhabitants, and eventually moved, after her husband's death to the Dutch area in what is now the Bronx in New York. There she refused to keep guns in her home and was eventually killed with several of her children by a group of indigenous Siwanoy who were responding to massacres by the Dutch.

When she died, John Winthrop was tickled pink.

This is all fascinating in itself, and the deadly hate over what now seem like such petty differences over doctrine reminds us that closed minds and vicious disagreement are far from new. In fact, they are pretty much part of the founding of this nation.

To read more about this book, see Publisher's Weekly and Bookpage. For a sample chapter, click here.

The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 by James Shapiro

There is so much of interest here in this life-and-times book about the year 1606, when William Shakespeare wrote Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. Shakespeare had been very much an Elizabethan playwright, but in fact he wrote some of his best work during the early years of the reign of James I.

We follow Shakespeare and the success of his company (The King's Men) and also the politics of the day: King James at the beginning of his reign; the Gunpowder Plot, which came very close to blowing up dozens of members of parliament; the hunt for and execution of the Catholic rebels; and then the repression of all kinds of Catholics.

We learn about the fear of witchcraft and the elaborate, expensive entertainments favored at the court, and then there was the Plague. Shapiro looks at what the plague did to theater as well as the general population.

And meanwhile, Shakespeare was dashing off those magnificent plays, with many references to things of special interest to the people of 1606.

Bone Music by Joel Peckham

There is confessional poetry in which the poet displays her or his life's suffering as the subject of the work. And then there's Joel Peckham's Bone Music where each poem is colored by and even organized by the great personal disaster of his life--the deaths of his first w

ife and oldest of his two sons in an automobile accident-- but everything is also transmuted into a kind of brilliant dark prophesy that points us in a certain direction, and changes how we see.

The poems seem to have been written in the presence of both his living and his dead family, his experience the necessary spine of his poetry and the substance of his metaphors and insights. Miraculously, he never separates himself from those of us who have not had losses like his.

Peckham's work is precise in its diction, but never showy. It is anything but a light read, but it is uplifting in its aliveness. Part of his effect comes from how he eschews white space around his poems much of the time so that when there is a hanging indent or a double space, it has a lot of power. There are plenty of phrases one could quote here, but Peckham's greatest strength isn't diction but movement. He refers to music frequently, and the long lines of his poetry, like music, flow in time and never hold still.

The long poem "Arrhythmia" (p. 50) is in the middle of the book. It has sections about himself as a child as well as about himself as a father. It deals with memory, but particularly about memory's work of erasing and revising. Here is the 4th section, quoted in full (apologies for my inability to get the layout right--you should read the book!):

4.

I fear most, not the forgetting but how it vanishes—erased, released so

we might better keep our grip on what and who we would believe we were

and are, the way the mind replaces what we see and hear and sense—

adding details, writing over thoughts until it is another thing entirely.

When does the name of the child separate from the child, become the

only child–-only the child—the photograph replace the skin alive with

| heat. So much is story. Words replace the blinding blue of a winter sky,

the actual steam release of air-brakes, bloom of breath, exhaust and

bitterness of cigarettes which is a taste a touch a sound embodied and

the body, a refracted image, broken into wholeness.Two sections further, section 6 tells the death of his son briefly, clearly, and simply. Peckham shows great grace in his invitation to us to know the simple facts, to ground us for the complex repercussions and struggles that surround the facts.

The final long poem, "The Locomotive of the Lord," twelve pages in nine sections, brings it all home with its transitions and connections, especially the unpunctuated phrases that end each section and become the beginning of the next section. The language is plain, the lines often all the way across the page like prose. In the end, what we have here is a life built of whatever materials the poet has been granted: disasters in the world, a brutal personal story, music--both instruments and words, visual patterns of black ink on white paper.

A Pure Heart: A Novel by Rajia Hassib Reviewed by Marc Harshman

With her second novel, A Pure Heart, Rajia Hassib establishes herself as one of the most important novelists in America. Her powerful story details the ways in which the primary narrator, Rose, tries to understand the death of her sister from a terrorist attack in Cairo. Rose’s sleuthing mimics her work as an archaeologist at the Met in New York City. Complicating her search for answers is the unwitting role her American husband from

West Virginia may have played in her death. As a New York Times journalist he’d brought the sister and eventual terrorist together. With meticulous detail Hassib gives us a compelling glance into the complex world of Egypt during and after its unique chapters in the Arab Spring, all the while spinning a tale of mystery that rivals the best page-turner.

The representation of Rose’s comfortable middle-class parents is deftly handled. Although middle-class, and clearly devout, they are also not fundamentalist and it is by their nuanced portrayal I feel American readers might be truly enlightened.

Bearing even greater testimony to Hassib’s talents is that the bomber is not only a fully realized character he is, in his way, a sympathetic one. These characters, as well as others, all spring to life with such authenticity I came to feel as if I knew them. And even as Egypt is revealed with veracity, there is a growing understanding of how specific places, small places like a bench or back porch, a random street corner in Manhattan or Cairo can make one feel “at home” as much or more than being with the people who live in these places. “Places don’t care where you were born or how long you’ve lived in them. If you like them and make the effort to know them, they make you feel like you belong there. It’s their gift to you. Their way of liking you back.” Marvelous.

Besides being a gripping and inspiring story, I came away fervently hoping this book will be widely read for its unflinching and honest portrayal of the complex faith that is Islam. Rose does not flinch at seeing the evil in religious violence but she is clearly in love with the best her Islamic upbringing has revealed to her. And, in the end, it is her devoted struggle to being a good believer that unties the knots not in her sister’s death so much as in the mystery of her own life and relationships.

It is quite simply a remarkable novel I highly recommend.

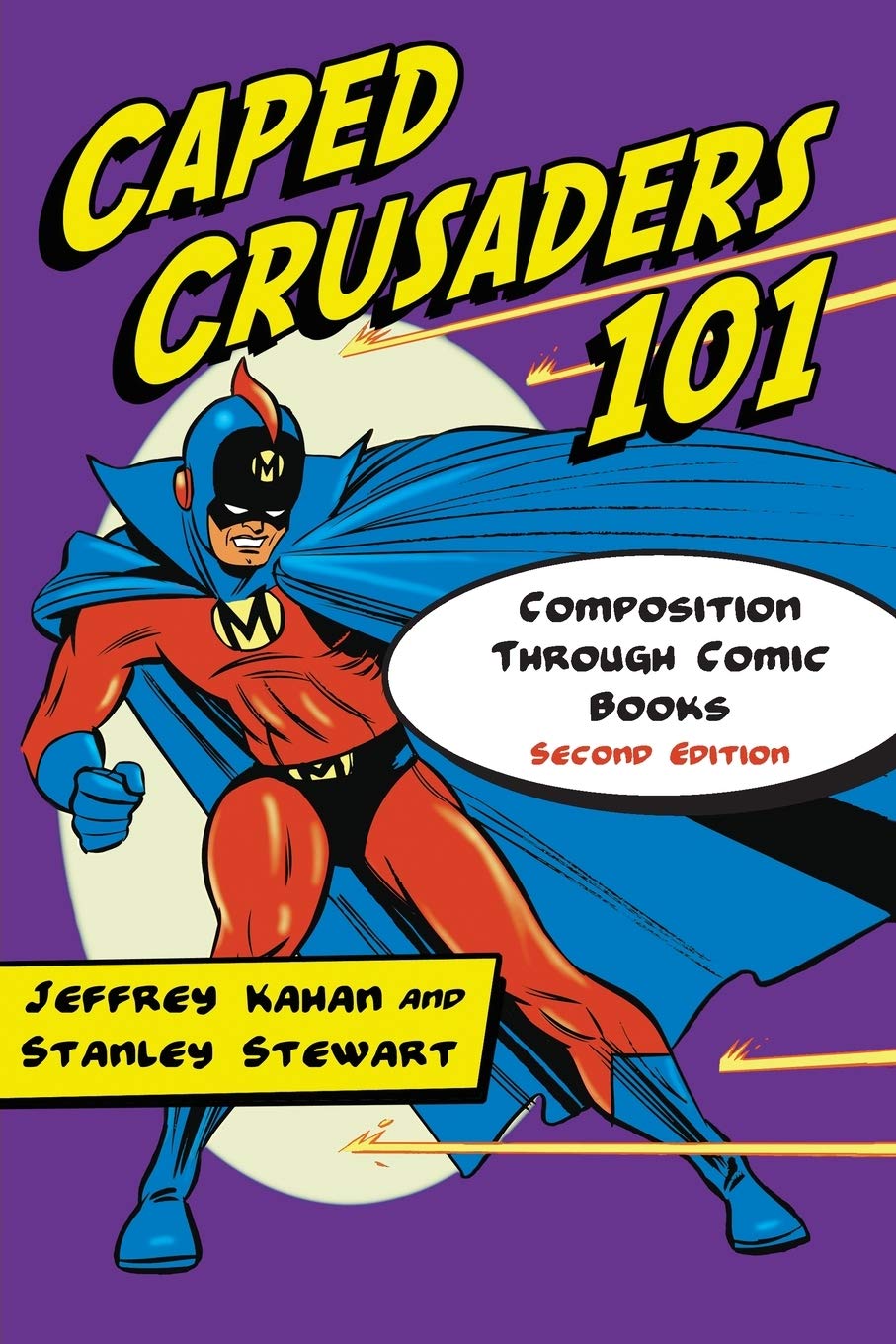

Melitte by Fatima Shaik

This is a children's chapter book that should not be limited to children. Published in 1997, it falls into the category of a slave story, but like all the best fiction, is thoroughly particular, set in Louisiana in the 18th century where one poor family has a lone slave, Melitte, who is at once abused and necessary to the survival of the family.

It is a miserable dirt farm the owner won in a card game, and he and his French wife and Melitte all work. Madame hates the child, and Melitte gradually realizes that while everyone works hard, Madame is unfairly cruel to her, and while Monsieur is less cruel, he too makes it clear that she, Melitte, is of a different status from the adults. She yearns for her mother, cuddling with a blanket that she associates with her. Melitte gradually picks up information, comes to understand what it is to be a slave.

Then Madame has a new baby, Marie, who Melitte loves passionately and essentially raises. She learns

near the end (adult readers pick this up much sooner) that Marie is her half sister-- that Monsieur is Melitte's father, and one reason Madame hates her so much is that she suspects this. The details of petty tyranny are especially well done, including how the adults try to separate Melitte and Marie. The book also recognizes that poor people of whatever color suffer, even if they also are cruel.

The close of the story leaves Melitte about to escape: there is a real hope that she has a better future ahead of her, but she and her beloved little sister will be separated.

Kirkus called the book "Full of period detail and vivid sensory writing, [providing] an aching answer to the question, ``What was it like to be a slave?'" It was originally labeled for kids 10-14, but of course the labeling is part of the problem: the whole industry of books written for children works too hard to figure out how to market to kids. The handful of children who could read in previous centuries read far more complex books: the Bible, adult novels

In the end, Melitte is best read simply as a short novel in the voice of a child. It is out of print, but available online from used book dealers (there are many including Bookfinder.com)-- one of the great boons of the Internet age!

Critique of Western Philosophy and Social Theory by David Sprintzen Reviewed by Joe Chuman

David Sprintzen's Critique of Western Philosophy and Social Theory, is a work bearing a prosaic title with broad ambitions. Published in 2009, the book is a hidden gem of philosophical analysis that presents a blueprint for the reconstruction of contemporary society.

Sprintzen is a Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Long Island University and a life-long political activist, who founded, and for many years, chaired the Long Island Progressive Coalition. In this work the philosopher-activist, brings his philosophical erudition to the fore while hinting at the practical applications of his philosophy for social policy.

Sprintzen, who has published two texts on the philosophy of Albert Camus, and is a scholar of the thought of the American philosopher, John Dewey, in this work is committed to nothing less than critiquing and reformulating the metaphysical underpinnings of modern society. His thought is wide- ranging, yet grounded in a unifying concept. His thesis focuses on the metaphysical mistakes that have shaped modern values and habits of thoughts. With the spirit of Dewey looking over his shoulder, Sprintzen contends that the cardinal error plaguing modern life is the atomization of things, ideas and experiences we engage. However differentiated and independent from one another phenomena appear, Sprintzen asserts that the fabric of reality is unified and all things at ulterior levels are interdependent.

We live within the context of mistaken paradigms, and Sprintzen's ambition is to radically transform how we assess reality at its foundation. He states,

It is one of the central theses of this work that we are currently in the midst of a global cultural and metaphysical transformation at least equal in scope to that which began to transform the planetary culture four centuries ago. Our fundamental modes of thought and action, institutional structures, personal identity, economic development, and relation to nature, all require radical revision if human life on this planet (and beyond) is to survive and prosper...My task in this work will be both to critically evaluate the contours of that transformation and then to outline the structures of an alternative metaphysic and sketch a frame for the social and institutional order it suggests.

This, to say the least, is a comprehensive task, and it is not surprising that the author begins his treatise with the conflict between religious and scientific worldviews. To his credit, Sprintzen affirms that religion has played the necessary function of providing human beings with a sense of meaning and place in an otherwise absurd reality. We are mythopoeic beings who find meaning within narratives. The scientific revolution, emerging in concert with Protestantism, is at stark variance with religious explanations of reality, and has replaced them with alternatives, that while creating the foundations of modernity, have radically alienated us from nature and legitimated a worldview of isolated individualism, competition, unbridled capitalism and dominion over others. Implicit in Sprintzen's project is the need to reconstruct a narrative that is updated and fitted to the empirical findings of our age.

Though he does not use the term, underlying Sprintzen's metaphysics is the notion that reality is an organic unity, and viewing its constituent parts as independent entities separate from each other partakes of a false understanding and misconception that leads to disastrous consequences.

Sprintzen applies this analysis to a very broad range of phenomena, inclusive of subject-object dichotomies found in Aristotelian sentence structure and logic, Cartesian dualism, and Newtonian determinism leaving us wanting for purpose. Of greatest moment to the author is the mistake we make in asserting ontological individualism that situates the person outside of society and is blind to the thoroughgoing social dynamics which shape the person, including our subjective sense of individuality. Here Sprintzen finds an ally in Karl Marx's observation that the human essence is “... the ensemble of the social relations.”

Individualism's most powerful expression is deployed economically in the market, which by its own logic sees no higher gratification than the satisfaction of the isolated self. “To the extent that we view ourselves as essentially self-encapsulated individuals – the economist's proverbial 'economic man,' for example, always looking out for 'Number One' – to that extent society is nothing but the practical instrument of a calculated strategy, of which other people are the present instruments and The Market the primary vehicle of social cohesion.”

Individualism is a species of reductionism, which is the fallacious paring down of complex realities into a single phenomenon or explanation. Sprintzen's anti-reductionism takes him beyond the human realm into the field of quantum physics and Heisenberg's uncertainty principle in which he finds validation for the emergence of new phenomena which a strict determinism or a notion of reality comprised of atomized parts cannot provide or explain. It is here that Sprintzen introduces the concept of “emergent phenomena” which are those “whose nature and operation cannot be completely explained by a description of the behavior of their constituent parts.”

Reality is complex and multilayered. Different systems function and can be explained according to their own laws. Yet the laws that explain phenomena within systems cannot provide an exhaustive explanation when systems intermingle or overlap. So, as Sprintzen notes, “...emergent phenomena are best thought of as themselves elements of emergent structures that express the unique organizational properties and powers of distinctive fields or levels of reality.” For example, “...gravity conditions life, and no life can violate gravitational laws, but gravity does not determine what living things do.” Or, to provide another example, “Language...requires brain cells to transmit electrical signals, but none of those cells have or understand language.”

It is the relations of these disparate systems that create “fields,” and the concept of fields is pivotal to Sprintzen's metaphysics. Fields give rise to the semi-autonomous reality of emergent structures and also provide a resolution to what Sprintzen acknowledges as the so far intractable problem of the relation of freedom and determinism. To complete his analysis, Sprintzen discusses the complexity of consciousness, which also partakes of an analysis of fields. He notes,

Self-consciousness involves the capacity of an organism to be at the same time – in one unity act – both the subject and the object of its own awareness: to be an object “for itself.” We are thus confronted with a unique emergent field characterized by both irreducible subjectivity and sociality, neither of which furthermore, are reducible to the other. Consciousness is the subjective structure of that experience. Self-consciousness is the meaningful organization of that experience as it locates itself within its own meaning-field.

Our experiences are objectively knowable by others from the outside, but subjectively they remain private and unknowable. The objective standpoint tells us nothing about the subjective meaning, intent, or even the likely behavior of the emergent experience viewed subjectively.

The reality of systems in relation to each other gives rises to fields such that this broader reality is not explicable or reducible to the constituent elements in any system alone. This understanding opens us up to the emergent, the new and, in regard to consciousness, freedom. It also serves as the basis of a fresh metaphysical understanding that should guide our thinking as we move ahead.

With his approach that refutes determinism and reductionism across the entire range of phenomena – physical, social and cognitive – Sprintzen claims “...to suggest the fundamental inadequacy of that classical way of thinking – first systematized by Aristotle more than 2,300 years ago and which has dominated Western thought ever since – and to offer a conceptual frame for an alternative frame with which to replace it.”

Before hinting at the practical applications of Sprintzen's metaphysical reconstruction, I think it is most useful to briefly return to his discussion of the fallacy of individualism and the contrasting social nature of the human person. Here the author is at his most demonstrative. He begins his chapter on “The Webbed Self,” with a virtual rallying cry, “By now one thing should be totally clear: individualism is a theoretically untenable and socially destructive doctrine. It might well be called the social disease of modernity, completely mangling any capacity to understand the process by which society produces and and nurtures individuals into adulthood.” For Sprintzen, individualism is “...simply the atomism of the social world...” The target of Sprintzen's ire is rendered transparent when he says, “It (i.e. individualism) serves as a narrow justification for a narrow self-seeking (often profit-maximizing) egoism.”

Despite the ontological fallacy of individualism, Sprintzen, nevertheless, acknowledges its profound historical role as a liberatory propaganda tool in transforming static, class bound, repressive societies and freeing persons from lives of perpetual misery at the hands of autocrats. Yet he claims that the historical function of individualism should not be mistaken for its theoretical adequacy. Nor should we deny its disastrous consequences as we move forward.

In discussing the mistake of the individual as prior to and over against society, the author makes the critical distinction, as implied earlier, between individualism as an ontological category and the moral value of individuality as a quality of character. Here he explicitly borrows from the thought of John Dewey and invokes Martha Nussbaum's approbation of human flourishing as among the most worthy of social goals. Indeed it is society that gives birth to individuality and is one of society's most valued purposes.

Here I find an omission in Sprintzen's treatment of individualism. As a student of human rights and a staunch defender of civil liberties it seems to me that Sprintzen's critique of individualism would merit discussion of the rights tradition in the West. Liberal democracy, which no doubt he supports, requires both democratic elections as well as respect for rights held by individuals. Ontological individualism as a basis for rights has a long pedigree most powerfully articulated by luminaries of the Enlightenment such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Immanuel Kant. In more recent times, there has been debate about the foundation of human rights including arguments demonstrating how humanity, possessed by individual persons, gives rise to rights. Sprintzen's thesis, which denies the independent status of individualism removed from our social natures, would be strengthened by interrogating the position defended by these classic figures, a mainstay of political philosophy, which many maintain is a prerequisite for a free, democratic society.

As he moves toward conclusion, Sprintzen applies his metaphysical analysis to the state and future of American society. A commitment to individualism has lead historically to a belief in unbounded expansionism, especially of markets. But this dynamic has run its course and has been exhausted. Among the consequences are the retreat into privatization, the erosion of community and its consequent loneliness. We suffer from a “celebration of commodities,” a narrowing of meaning, purpose and hope, among other social ills.

Sprintzen's solutions, as implied, are comprehensive. He provides the philosophical changes in vision that are necessary to provide for the survival and flourishing of the human future, without articulating specific policies. Again, his purpose is philosophical and only by extension political. He provides a map with the details to be filled in by others.

But his vision that emerges from his critique is clear, and there are hints of what society based on that vision would entail. We need a transformation of beliefs, practices, social institutions and personal character. Among the elements of his vision are the following: Economic activity should always be subordinate to the provision of the collective human well-being. Health care and social services shall be a right. Ecological sustainability, equity in the provision of basic necessities and racial and gender equality are required. Invoking Dewey again, we must employ intelligence and eschew outmoded ways of thinking to address our problems. But central to Sprintzen's aspirations is a revival of democracy, most organically expressed through a reconstitution of neighborhood life. We must move away from exclusive emphasis on the private sphere and come to appreciate how purported private interests need to serve the public and the common good.

In conclusion, Sprintzen does not posit utopia but does open us up to possibilities. We require a renewal of ideals, a commitment to the emergent and the new in concert with a naturalistic ethic and the deliverances of science. He provides an assessment of our condition which is far reaching, profound and wise. His critique is radical and his vision humane.

David's Sprintzen's Critique of Western Philosophy and Social Theory lives up to its name. And those who choose to follow the thought of this very adept philosopher will be well rewarded.

GENRE AND FAST READS

Fellowship of the Ring (first book of Lord of the Rings) by J. R. R. Tolkien

I was thoroughly engaged by this, although sometimes impatient with its slow exposition. Sometimes, too, I was annoyed with the awkwardness of the omniscient point of view, and repelled too often by general sexism and the soldierly band-of-brothers. It is brilliant and also deeply conservative: I'm thinking particularly of Frodo's faithful native--I-mean lower-class-- Hobbit companion/servant Sam, and the association of whiteness and light with the goodness of the elf queen versus dark shadows and dark riders and the dark eye of Sauron.

On the other hand, I was never bored by the landscape writing, which Tolkien does extremely well, and I am looking forward to reading the next book. I also have to say it is hard not to visualize the characters as Elijah Wood, Orlando (sigh!) Bloom, John Rhys-Davies, et alia.

Forest Mage (Soldier Son trilogy book 2) Robin Hobb

I have my continuing complaints with this most recent Robin Hobb fantasy series: it could have been shorter-tighter-faster; Nevare the protagonist is whiny and often too slow on the uptake. She also telegraphs what's coming a lot–but–but! when she's good, she's very, very good. Her magic stuff is always under control, and she treats it, in this 18th/19th century world as something cultural: the Gernians have a sort of western-scientific technology, but they also know that the iron they shoot stops or neutralizes the magic of another group called the plainspeople, who are more than a little like the Plains tribes of the United States. Then there are the so-called Specks, a forest people, who have a much stronger kind of magic related to their great sacred. sentient trees.

Action scenes are businesslike and quite good, especially Nevare's escape from prison at the end. Sex suddenly blossoms, unlike inn her other books: the Forest People, in particular, have a matriarchy where women do all the outreach for sexual partners, and a good time is had by all.

Hobb does women well, even when they are the oppressed darlings of the Gernians.

Also really interesting and fresh is how Nevare gains an enormous amount of weight, for which there is an explanation. He is a Great Man to the forest people, and humorously obese to the Gernians. The body image stuff is believable enough in a young man who hoped to be a physically active military officer, but the insight of how it feels is very female. Hobb odrwn has female insights that she uses on male characters without turning them into women.

See my notes on the first book of the trilogy, Shaman's Crossing, here.

The Last Coyote, Trunk Music, Angels Flight by Michael Connelly

More of my continuing self-indulgent reread of Connelly's Bosch books. Typical of series writers, I think: Connelly's early middle books are best. The Last Coyote is the one where Bosch is on leave for knocking Lt. Pounds through a window and is being forced by the department to see a shrink. So, on his own, he solves the mystery of his mother's murder. Bosch's obsession with his calling works well. Assistant Chief Irving Irwin's emotions are a little mysterious, but Connelly is good on people with mixed motives.

The next book, Trunk Music, ends with Bosch marrying Eleanor Wish-- and also has lots of Kiz and Billets, Jerry Edgar and Irvin Irving and Chastain of IAD. Lots of Las Vegas as well as Los Angeles. Not as perfect as some, but plenty satisfying.

And Angel's Flight is the Bosch novel when I realized I was a fan: at least partly because I now go to Los Angeles and I saw the real inclined railroad called Angel's Flight. Interestingly, this novel is almost all detecting and police procedural--very little in the way of shoot-outs, for example. There is plenty of ugliness though, in particular the discovery of a website with child pornography hidden "behind" it. The technology in the books is always precisely dated, which means it feels historical instead of out-of-date. Lots more interesting about his now-familiar cast of characters (Chief Irving, Kiz and J. Edgar). Bosch has stopped smoking. There is very little of him in physical danger. A random sniper shoots up his and J. Edgar's car (a riot that doesn't quite happen). There's an abusive rich man, an evil IAD officer, the reappearance of Roy from the Las Vegas strip joint, the disappearance of Eleanor Wish. You are so busy moving forward with the detecting and actual story that you don't notice it's more character driven than most of his.

One other recurring strategy that I like: as he is precise about the dates of his technology, so he is about current events in Los Angeles, and, as in Angel's Flight, he lays out a possible repeat of the Rodney King rebellion as an interesting red herring, while the motives of the murder turn out to be far more personal. Which is how a lot of things are in life. Under the cloud of great events, but we go about our small lives.

THINGS TO READ ONLINE & MORE

Belinda Anderson sends, in response to last issue's reviews of two books by Anne Brontë, this article about Anne's lost second novel. See Belinda Anderson's's notes on the Brontës below.

Issue 98 of The Jewish Literary Journal is now online.

Innisfree 33, the fall 2021 issue of the Innisfree Poetry Journal, is now available at www.innisfreepoetry.org. In this issue, we take a “Closer Look” at the work of David Salner with a number of poems from his books.

Lit Hub suggests 22 novels for this fall.

READERS RESPOND

Belinda Anderson writes, "The Brontë sisters are endlessly fascinating to me. I think this line from one of Emily Brontë's poems characterizes all of them: 'No coward soul is mine.'

" I'd like to recommend Charlotte Brontë: A Fiery Heart, by Claire Harman. I found it a detailed and insightful examination of the lives of the entire family. 'Careful, well-judged, nicely written,' The New York Times said in its 2016 review. The Washington Post review said, 'Harman's story is about how writers write.' There's also a very interesting piece on jstor.org that begins with this intriguing sentence: 'One can only imagine what was going through Charlotte Brontë's mind the day she knelt by the blazing fireplace in Haworth Parsonage, her family home, with her dead sister Emily's unfinished manuscript clutched in her hands.'"

ANNOUNCEMENTS:

Interview of Jane Lazarre at Lilith Magazine about how this age of crisis affects our inner worlds.

Fatima Shaik wins Louisiana Writer Award!

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 217

October 23, 2021

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Meredith Sue Willis's Bookshop.org Store Contact

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

"Grandma Shiksa," New Short Story by MSW

Fall 2021 Issue of Persimmon Tree

Now Available:

New Issue of The Hamilton Stone Review #45Poetry: Janice Harrington, John Guzlowski, Rochelle Robinson-Dukes, Steve Fay, Clint McCown, Sally Zakariya, Sarah McMahon, John Repp, Jane Simpson, Changming Yuan, Tony Beyer, Nancy Smiler Levinson, Mark Young, Lisa Zimmerman, Glenn Armstrong, J.D. Nelson, Heikki Huotari, Natalli Amato, Leonore Hildebrandt, Kelly O’Toole, Alison Thorpe, Tim Suermondt, Madronna Holden, Cheryl Denise, Stephen Gibson, Jay Jacoby, Benjamin Nash, Laurinda Lind, Ayşe Tekşen.

Prose: Rosaleen Bertolino, Amy Cotler, Carole Rosenthal, Lynda Schor, Kelly Watt.

If You're Going to San Francisco...

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 2021

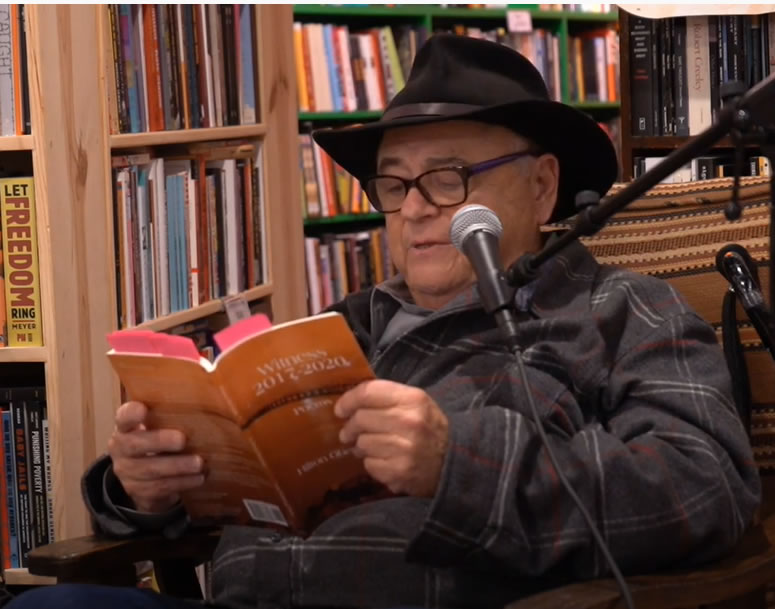

10 PM Pacific – 1 AM EasternHilton Obenzinger reads from his new collection, Witness 2017-2020

The Green Arcade 1680 Market Street @Gough San Francisco CA 94102 (415) 431-6800

Contents

Book Reviews

Announcements! Things Happening!

Genre Selections

Recommendations and Reader Responses

Reading Lists

Things to Read Online

Irene Weinberger Books

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue # 217Reviews are alphabetical by author, not reviewer.

If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW.

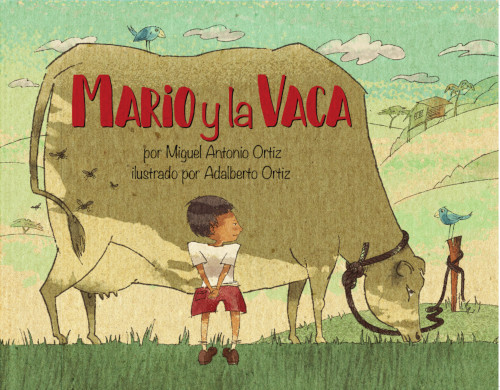

Caped Crusaders 101: Composition Through Comic Books by Jeffrey Kahan Recommended by Peggy Backman

A Darkness More Than Night by Michael Connelly

City of Bones by Michael Connelly

Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier

A Pure Heart by Rajia Hassib

Renegade's Magic by Robin Hobb

Breaking Light by Jane Lazarre Recommended by Miryam Sivan

Jill Lepore's America: These Truths Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Circe by Madeline Miller

Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys Reviewed by Ingrid Blaufarb Hughes

Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney

Shakespeare in a Divided America by James Shapiro

Recommended by Daniel GoverThe Red and the Black by Stendhal

An article in the Atlantic called "Why Are E-Books So Terrible?" caught my attention, and might interest you too. The writer is Ian Bogost, a contributing writer there and director of a program in film & media at Washington University in St. Louis.

As a big fan of e-books, I prepared myself to be offended, and I was, but only mildly and especially by some sloppy writing by Bogost and by his neologism "bookiness." What an unpleasant word. I was also annoyed by several of his unsupported statements--that no self-published books are ever laid out "in a manner that conforms with received standards"-- and for his insistence that the technology of books has hardly changed over the centuries. He barely mentions moveable type, and skips over major innovations like popular paperbacks.

On the other hand, he agrees with me that e-books work best in genres with a strong narrative voice. He says "fiction in general and genre fiction—such as mysteries, sci-fi, young-adult fiction, and romance" work especially well as e-books. I'd add to that list biography and history and journalism without many citations. In other words, stories are great in the endless flow of the digital screen. What is much harder in an e-book, I agree, is to have what he calls random access, " the ur-feature of the codex.... for skimming back and forth....For readers who like to move back and forth, ideas are attached to the physical memory of the book's width and depth—a specific notion residing at the top of a recto halfway in, for example, like a friend lives around the block and halfway down."

This is a fair critique of e-book technology and something I'd really like to see the engineers work on. It can even be difficult to find your place again in an e-book. I also agree that e-books support the reading habits of people who like to carry a large number of books at once, and this emphatically includes me. My Kindle has all of Jane Austen, George Eliot, Dickens, the Brontës, Trollope and more-- a a slew of out-of-copyright favorites. Digital reading I agree supports those who love a direct flow, endless story, and don't care so much about annotating. Bogost is more than a little snarky about genre fiction (although he insists he's not), and reveals that he reads mostly scholarly and trade nonfiction.

He also finds it aesthetically displeasing when books all look the same. Thus Bogost, like a lot of my friends, values books as objects along with what they communicate to us in the text. He says, " I also can't quite wrap my spleen [my spleen???] around every book looking and feeling the same, like they do on an e-book reader. For me, bookiness partly entails the uniqueness of each volume—its cover, shape, typography, and layout."

I read codex books too, of course. Right now, I'm reading on my Kindle, Le Rouge et le Noir, in English (either free or almost free–I can't remember if I got it from the Gutenberg Project or on sale from Amazon) and a Michael Connelly crime novel that I borrowed from the public library. I am also reading a huge and gorgeously illustrated physical art book from the Metropolitan Museum that is the catalog of their recent exhibition of Medici portraiture, and I just ordered a paperback copy of a fantasy novel through the used book site Bookfinder.com . It wasn't available as an e-book at the library, and I avoid paying Amazon's full (and high ) prices for e-books.

In other words, why bother to hate e-books when they are one of a variety of ways to do your reading? And, honestly, what's not love about the wonder and security of carrying Jane Austen's entire oeuvre around in your shoulder bag?

One Kindle book I got on sale at Amazon for a couple of bucks, and have largely laid aside, is Pat Conroy's Prince of Tides.

Could someone help me with Pat Conroy? Lords of Discipline wasn't bad, but does anyone have any context/help for me with Prince of Tides? It's another Southern novel with a prominent beautiful woman who goes crazy in New York City (like William Styron's first novel Lie Down in Darkness).

Prince of Tides just irks me with its mid-twentieth century Southern male protagonist going on and on about how his is the most dysfunctional family ever, absolutely amazingly super dysfunctional and he is also an amazing super dysfunctional mess. The biggest most southern mess ever bred in the South. Did I mention the narrator is Southern?

Anyhow, does anyone have an opposing point of view on the novel that might lead me to finish it?

REVIEWS

Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk by Kathleen Rooney

This was an unexpected pleasure--unexpected because while I often admire the writing in recent best sellers, I'm not usually caught up in them the way I was in Lillian Boxfish. Rooney came up with her novel after reading in the archive of real-life poet and advertising writer Margaret Fishback. Lillian Boxfish is a fictional version of Fishback's life that uses Fishback’s actual poems and advertising copy.

I was

expecting something very light and perhaps even frivolous, but it turns out that while that style, light and witty, is the style of Lillian Boxfish’s 1920's and 30's poems, she was highly ambitious. As the novel goes on, we also learn about how she confronts aging, a mental breakdown, and the loss of love.

The novel has a simple, strong structure: on New year’s eve 1984-85, days after the Subway Vigilante's attack on some threatening teen-agers, Lillian, who is in her mid-eighties (a child of the twentieth century) walks from Murray Hill to Wall Street in Manhattan and back, meeting all sorts of people, including old friends and new and a trio of amateur muggers. These walking chapters alternate with Lillian’s life story from the period pieces about being a young in Manhattan in the early twentieth century to her years as the highest paid advertising woman in the nation (as was Margaret Fishback).

Gradually these past sections become darker: Lillian falls in love and when she marries and becomes pregnant, she loses her job at R. H. Macy's. Gradually we hear about her break-down and her deep disappointment at a new world where her successes are forgotten and devalued.

Rooney writes the past in the past tense, the vigorous walk through Manhattan in the present tense.

I did have a question about stylish Lillian's footwear. I believed that she took the walk, or at least was willing to suspend disbelief, but I kept wondering what were the walking shoes of a woman in her eighties who always dressed for going out. Sneakers? Surely not Lillian. But heels? Impossible!

In the end, though, forget the footwear. The structure works to hold up Lillian's story and also perhaps the story of Lillian’s greatest love of all, which is New York City.

The novel came out in 2017. It was praised at the time by the Chicago Tribune : “While the novel's structure can at times feel claustrophobic — this one-to-one correspondence between the triggering present and the recalled past — Lillian's voice is anything but. Highly energetic and supremely self-knowing, not a little boastful and perpetually clever....”

Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier

I liked Cold Mountain a lot, especially the Ada-Ruby parts with all the old time lore about farming and when to plant and herb remedies. The runaway Confederate soldier Inman is an excellent character, fleeing the war for his home in western North Carolina. Some of his adventures take on a southern Gothic, even hallucinatory tone, but maybe I was wrong to expect realism.

At any rate, it captures a lot about the attitudes and actions of people in the Southern Appalachian mountains as the Confederacy was falling apart. I have been reading Civil

l War novels and histories since I was in high school when West Virginia had its 100th anniversary-- seceding from Virginia to go with the Union.

The end seemed oddly dreamlike, at once too perfectly cruel but with an epilogue too perfectly upbeat and uplifting.

In an odd way, I think the book was too artful, and for all its unexpected, impossibly sudden turns and twists, not open-ended enough. Too carefully constructed, perhaps.

As Kirkus said in its review when the book first came out in 1997, "There's no doubt that Frazier can write; the problem is that he stops so often to savor the sheer pleasure of the act of writing in this debut effort." A lot of the full review is very positive, by the way, and it is far from a beginner's novel, but there is a little inebriation over the delight of writing, a little showing off what I the author can do.

None of which stopped me from liking it a lot.

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys Reviewed by Ingrid Blaufarb Hughes

In The Wide Sargasso Sea Jean Rhys sets out to write the life of the character Charlotte Bronte created in Jane Eyre, her “madwoman in the attic.”

Jean Rhys’s Antoinette Bertha Mason lives in Jamaica not long after the British ended slavery in their West Indian colonies. Antoinette’s father has died; her mother can barely feed her two children, the younger of whom is unable to walk or talk normally. Several people who choose to stay on with the family, despite not being paid are also part of the household, most importantly Christophine, a strikingly tall, black, spare woman who mothers Antoinette when her mother is unable to.

The first part of the novel is from Antoinette’s point of view. Because of the family’s poverty, they are shunned by the white community. The Black children taunt Antoinette, calling her family “white

niggers,” suggesting that social standing is as important as skin color to the definition of the N-word. Even Christophine, who Antoinette’s mother says was “a gift from your father when we married” is shunned by other black people, perhaps because she’s from Martinique, perhaps for her connection with the impoverished and afflicted family.

Nothing Antoinette perceives is solid or settled and much is threatening. After her mother remarries, the family is attacked by Black and colored people and their house burnt down. Pierre, Antoinette’s brother somehow dies in the confusion. And a Black child, a playmate of Antoinette’s injures her badly by throwing a rock at her head. After this Antoinette is taken in by her Aunt Cora, the only kind and responsible relative she has.

Antoinette’s mother’s madness consists of childishness, increasing petulance and, after her son’s death, a deep narcissism.

Sent to live in a convent, Antoinette suffers dreams of fear and death. Her mother dies, evidently as a result of her madness. Causes of death are not precise in this world.

When the story shifts to Rochester’s point of view, we’re dealing with a complex character fully developped in Jane Eyre, where I’ve always had trouble with him: what cruelty to develop a strong connection with his daughter’s governess and then insist the governess attend dinner parties where he flirts conspicuously with another woman he can’t possibly like. Rochester isn’t named in Sargasso Sea, but he’s the same intelligent, changeable, sometimes cruel person we know from Jane Eyre, though younger. He marries Antoinette Mason for her substantial wealth, left her by her stepfather, which he needs as a second son who will inherit nothing. Their wedding contract gives her inheritance to him.

He goes through with the wedding and the wedding trip to a remote estate left Antoinette by her mother in a state of numbness. When he recovers and notices Antoinette’s beauty, they share a short period of happiness, though he is clear that he doesn’t love her and they have little in common.

To Rochester the wild forests of the island are alien, inimical. When Antoinette tells him that “...One of my friends said this place London is like a cold dark dream....” He replies, “....that is precisely how your beautiful island seems to me, quite unreal and like a dream.”

He turns against her in fear and disgust when he receives a letter from a man claiming to be Antoinette’s half-brother, (the son of her father and a Black woman), informing Rochester about Antoinette’s mother’s madness, and the wrong done Rochester by the friend who rushed him into marriage. In this world madness is inevitably passed on from parent to child, a deeply frightening and probably violent condition.

Rochester talks with Antoinette; he comes close to reconciliation. But it can’t happen. The cruelest blow for Antoinette comes when he has sex with a young woman who works for them in the room adjacent to Antoinette’s so she will hear them, reminding the reader of Jane Eyre’s subjection to Rochester’s flirtation with another woman.

When Rochester leaves for England he insists that Antoinette, now deeply depressed, go with him, refusing Christophine’s suggestion that he leave funds for Antoinette to live with Christophine on the island she loves. Feeling distrusted and tricked, he chooses dominance and punishment over love. Yet he has a moment when he wonders if he isn’t entirely mistaken in his belief that Antoinette is mad. Finally, shunned and punished, she does become mad.

Writers will be tempted to come up with alternate endings. But like Jean Rhys, we’re stuck with Charlotte Bronte’s ending.

The Red and the Black by Stendhal

Ah poor Julien Sorel: I still don't know whether to laugh at him or cry. After I finished this reading, I found my notes after I last read Le rouge et le noir in 2012, nearly ten years ago. I said then, "It was so good, mostly, some sloppy places, and passages that pulled back and commented on the action... sort of casually, as if with a loss of attention ....And I wish I had been surer of my history... And I'm not as fascinated by the vicissitudes of love as I used to be, but this was all small potatoes in a big book that just barreled through with Julien Sorel for whom you care so much, less for Mme. de Rênal , although her wishy washy sensuality is believable, but I really like Mathilde who is all about sneering at her suitors and the whole world, but finds herself amazed to be interested in 'the little' Julien, and how she makes the first move, and almost immediately insists on his coming to her bedroom. And they just do it, have sex."

This 2021 reading I felt more distant--I seem nowadays to be able to read and without demanding someone to identify with, because, really, who is there to identify with here? Ten years ago it was Julien, but now, not so much. The best part for me now is Julien's final days when Stendhal traces his changes as he faces/chooses the guillotine.

There is a brilliant passage in the final pages, Julien waking in a mindful state, appreciating all t he small things on his final morning. There is then a very short flashback to Julien asking his friend Fouqué to buy his body and give it repose in a certain cave with a view. We are deep in Julien's memory here, and in his present as he enjoys the freshness of the day as he takes his last walk, and then after the little flashback, the narrative simply elides to afterwards, Fouqué in his room with the body under the blue cloak. One is stunned to realize that is Julien dead, who was just a few lines ago pulsing with life. Then Mathilde comes, they bury the body. Mathilde imitates her ancestor by carrying the head herself. A final line of narration disposes of Mme. de Rênal. It is one of the best passages in prose fiction I have ever read--dependent of course on all the pages that went before.

Among the things that fascinated me this reading: how the handsome condemned Julien becomes the adored object of the local young women as if he were the Beatles in 1964. Also, Mathilde, once she has stopped being a rich diva, once she has given her all for Julien, is interesting, and one wonders what she'll be like when she's forty. She's the most interesting character in a lot of ways, although I was fascinated by Julien's struggle with class and his secret admiration for the late Emperor Napoleon.

Julien has ambition and cleverness and both good luck and repeated bad mistakes. But he makes a romantic end to his life, beloved by friends and lovers, popular with the public, still handsome. Some of his choices (not to mention Mathilde's romantic embracing of the severed head) are close to comic, but the social breadth Stendhal's brilliant insight into the short distance between life and death, makes the book, as its reputation says, a masterpiece.

The novel takes place after Napoleon had made it a policy to give room for talented men of the lower classes to move up, and in spite of Napoleon's end at Saint Helena, and in spite of the Bourbon restoration and the citizen king and all--the French aristocrats never could keep the lower orders down on the farm permanently again.

A Pure Heart by Rajia Hassib

This should probably come as "Readers Respond," because I read A Pure Heart by Rajia Hassib because Marc Harshman praised it so highly in Newsletter # 216. I'm so glad I read it. The main character Rose is complex and interesting, and the sad

fundamentalist/murderer is treated with compassion. Hassib does a great job of showing what attracts him to do his bombing, including his pride in his ability to build the device. Rose's husband is fine--the parents-- in fact, for me the only unsatisfying character is Gameela, who in her final POV section come across as really pushy and insistent on having her way. Hassib sets up a solid hypothesis for how these events might have happened, but I'm not sure that I believe in her Gameela's obsession with the boy.

How sweet the suicide-bomber-to-be and his pigeons are, though. And how well the relationship between Rose and her American husband Mark works. I especially love Cairo and Rose and Gameela's parents.

Rose's take on the USA is fascinating too: how women touch each other less here than in Egypt. Also, I had never ever read about a farm in modern Egypt before. Finally, Hassib handles her politics very well.

Listen to Marc's recommendation!

Circe by Madeline Miller

Miller has studied/taught Latin and Greek and mythology, which I expect is why her retelling of the Circe story never feels anachronistic: she has in study and imagination lived there. Although this is a frankly feminist/contemporary re-imagining of the myth, it stays with a kind of reasonable speculation about the ancient world and its gods and nymphs and heroes. Circe herself matures nicely (over several centuries!) and discovers herself.

Her lover Odysseus doesn't quite take shape for me, but their son is a fine character, as is Odysseus's son with Penelope, Telemachus.

Anyhow, the reader trusts Miller to deal honestly with the ancient epics and myths even as she offers an opposing view.

Admirably done.

Michael Connelly Report:

A Darkness More Than Night (2021 & 2018) and City of BonesWhen I first read A Darkness More Than Night In 2018, I wrote a pretty straightforward summary of the book, and seemed to appreciate it more than I did recently during my continuing chronological reading of the Harry Bosch novels. I wrote then that "we've made it [in the Bosch novels] to the 2000's, technology upgraded, and this one has both Bosch, who becomes the target of a set-up, and Terry McCaleb, who was the target of a set-up in the book just about him....minimal gore and violence, [and] I admired the double crimes that came together nicely but especially how Connelly made the two POV's work...[he briefly leaves open] the possibility that Bosch really did it– in fact, we know from looking at any Connelly book cover that there are lots more books to come starring B. Some weakness over McCaleb's quick willingness to accept Bosch as suspect, and some of McCaleb's work feels more like a writer than an investigator, but his heart transplant's effects on his life work nicely. Anyhow, Connelly, within his limits, does experiment and improve and try stuff. And so dependably gripping, plotwise."

This time, I was struck by how Connelly is playing with things–Bosch alternating with McCabe, and a lot of shade and suspicion cast on Bosch, including an ambivalent end about the morality of Bosch mostly but McCabe too. There are long less-than-fascinating court room sections–interesting, but not exciting enough. Toward the end it starts moving, and Connelly experiments with extra surprises from having two points of view–and Bosch from the outside isn't bad at all. Connelly's books are never really bad, but the experiments here feel like he was getting bored with his basic formula and fooling around for his own artistic satisfaction.

I then dashed through City of Bones. which was one of the very good ones, a kind of straightforward story without a tremendous number of subplots. The twists are set up nicely, there's a love interest (a lost love interest), a fair amount of police procedure, surprises that don't seem melodramatic. Connelly in full stride here, especially after the quirky split POV in A Darkness More Than Night.

Renegade's Magic by Robin Hobb

I finished the Robin Hobb Soldier's Son trilogy, with great relief. This last book seems to have gone on and on and on. Sometimes I was fully engaged and delighted (especially in the more familiar world).

I liked protagonist feisty Nevare's cousin Epiny, and a lot of the other minor characters.

Nevare, in his single or doubled spirited state, continued to be a whiner, determined to hate himself, It seemed like there were at least ten possible moments when Hobb could have pulled the plug and ended it the story, but she kept pushing it. The actual ending even with the weird return of the tree people and their creepy killer tendrils was actually pretty good, though. It just took too long to get there.

Also interesting was the concept of the Great Ones in the forest--huge individuals who eat in order to store up magic.

I am not an ideal reader of fantasy–the magic always feels slightly obstructive to me. Hobb's Farseer trilogy begins with what I consider excellent magic, usually presented one inexplicable phenomenon at a time like Forging which steals people's humanity. In the final book of that trilogy, the magic seemed to take over, and in the Solider's Son trilogy, it was too crowded with magic for me from the start. Maybe I prefer high fantasy, including hers, because it's easier for me to fill in the quasi-medieval backgrounds.

Still, she's always good, even if this series isn't my favorite.

See my responses to the first two books at Shaman's Crossing and Forest Mage.

Jill Lepore's America: These Truths Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Jill Lepore's one volume history of the United States These Truths is no less than a monumental, indeed magisterial, achievement. Her title, taken from the Declaration of Independence, is suggestive of the solidity of natural law. But the nation that was based on natural law principles was never secure nor certain. America has been a continuous process of contestation, contradiction and conflict, strife and the struggle for self-definition.

In her epilogue, she summarizes the theme that courses through her 900 pages of American history:

"The American experiment has not ended. A nation born in revolution will forever struggle in chaos. A nation founded on universal rights will wrestle against the forces of particularism. A nation that toppled a hierarchy of birth only to erect a hierarchy of wealth will never know tranquility. A nation of immigrants can never close its borders. And a nation born in contradiction, liberty in a land of slavery, sovereignty in a land of conquest, will fight forever, over the meaning of its history."

Jill Lepore is a Harvard historian and a staff writer for The New Yorker. Her ability to unify facts and personalities, most well known, many not well known but illustrative of their time, together with defining movements in American history, is prodigious. Lepore's style is captivating, and her language colorful and engaging. It kept me always eager to discover what came next. Though she underscores the novelty of the American experiment she doesn't lapse into hagiography nor is she cynical, while never permitting the reader to escape the nation's failures, especially its treatment of minorities.

In this regard it is clear that history is inevitably written through the lens of the present, and These Truths is most assuredly an historical narrative for our times. The passage cited above clearly renders that perspective. In our current moment of racial reawakening, I was struck by Lepore's emphasis on slavery and the struggles of Black Americans as intimately woven into the American narrative.

Lepore's repeated descriptions of relentless slave rebellions and Indian uprisings in the colonial period ensured they were not marginal to the colonists' political and philosophical views as they strove to break free from English domination. The American colonies and the Caribbean islands were functionally an economic and political unit and rebellions of enslaved people were frequent and feared. The value at issue was freedom, and Lepore draws the intriguing observation that the motivation that inspired the revolutionaries to free themselves from British tyranny was not only the tyranny itself, but the example set by slaves and Indians to be free of the oppression foisted on them by the colonists. As she notes:

"Slavery does not exist outside of politics. Slavery is a form of politics, and slave rebellion a form of violent political dissent...In American history, the relationship between liberty and slavery is at once deep and dark: the threat of black rebellion gave a license to white political opposition. The American political tradition was forged by philosophers and statesmen, by printers and writers, and it was forged, too, by slaves".

Slavery was continuously in the forefront of debate. Quakers forbade membership to slave owners and abolition was hotly debated in the colonial environment. Lepore observes that the adoption of the Declaration of Independence was a stunning rhetorical achievement, an act of extraordinary political courage. But is was also a colossal failure of political will, “in holding back the tide of opposition to slavery by ignoring it, for the sake of a union that in the end, could not and would not last.”

But the status of slavery by no means was the only division that characterized the American experiment from the beginning and throughout the nation's history. Divisions and conflicts provide a major theme among many around which Lepore constructs her sprawling narrative.

Ratifying the Constitution generated rabid debates between federalists and anti-federalists; debates surrounding the powerful federal government versus the states, which continue to cleave the nation. Lepore notes the conflicts between those who supported greater democracy as exercised primarily at the state level and those skeptical of direct participation in government by the people. For many, democracy was a form of government to be spurned.

The battle between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, she notes, was between aristocracy and republicanism. The conflict between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson was between republicanism and democracy, with democracy eventually prevailing as direct government increasingly shifted to the hands of the people. Jackson marked a shift in the presidency, He was the first candidate to actively campaign. He was also the first populist whose populism professed racial hierarchies and manifested the worst of populist tendencies. He waged ferocious campaigns against Native Americans and forcefully moved tribes from the their ancestral homes in a plan to move all Indians from the the southeast to lands in the west. According to Lepore, Jackson was “provincial and poorly educated” and he turned these characteristics and his lack of political experience into virtues.

There is an overlap between the emergence of populism and the religious awakening in the 1820s. At the time of the Revolution few Americans were church affiliated. With the Second Great Awakening, evangelical Christianity spread widely. Promoting the equality of souls, it spurred a democratizing effect that animated political culture. And since churches were greatly sustained by women it encouraged women's engagement in political movements. In contrast to today's fundamentalism, the evangelicalism of the day was active in the abolitionist movement and in promoting the interests of women, among them temperance, considered a progressive cause.

Lepore gives great weight to the role on the growth of technology and its impact on the political culture on in the early 19th century. We usually think of the Industrial Revolution emerging in the post-Civil War period, but she describes he development of steam power, the telegraph and the emergence of factories in the early decades of the century. These developments transformed the relations of men and women, workers to bosses, and a fervent belief in progress. It also spurred immigration, mostly of Germans and Irish and provoked nativist backlashes.

And there was always the issue of race. Lepore introduces Maria Stewart, a figure who most likely does not appear in standard American history texts. A free Black from Boston, the author depicts her as reflecting a fusion of Christian revival and anti-slavery politics. Stewart caught the attention of the famed abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison who took her on as a writer. Basing her arguments on scripture, she wrote and railed against slavery. Most interesting, was that in this early period, Stewart addressed mixed audiences of both women and men, Blacks and whites together.

In the antebellum years, Lepore stresses that America was a nation divided, slavery providing the major fault line. She amply discusses the role of Frederick Douglass, noting that Douglass was the most photographed personality of the period. In a way that perhaps presages the impact of the internet, Douglass believed that the new photographic technology was a powerful tool in proliferating the abolitionist cause. With compromises, debates, speeches and struggles, and John Brown's raid at Harper's Ferry, Lepore depicts the 1850s as moving almost inevitable to the cataclysm of Civil War. When the War came, it was unprecedented. Typical of her prose, Lepore writes:

"The Civil War inaugurated a new kind of war, with giant armies wielding unstoppable machines, as if monsters with scales of steel had been let loose on the land to maul and maraud, and to eat even the innocent. When the war began, both sides expected it to be limited and brief. I instead it was vast and long, four brutal wretched years of misery never before seen.

In campaigns of singular ferocity, 2.1 million Northerners battled 800,000 Southerners in more than two hundred battles. More than 750,000 Americans died Twice as many died from disease as from wounds. They died in heaps; they were buried in pits."

Perhaps because he has received voluminous treatment elsewhere, Lepore's discussion of Abraham Lincoln is surprisingly limited. She focuses on his early years and the contrasts of his anti-slavery views with those of Stephen Douglas. As Lepore notes, Lincoln grounded his views in American history, the Constitution, noting also that the thought of Frederick Douglass was an important influence.

Emancipation renewed the debate as to what exactly was meant by the notion of “citizen.” Along with a host of contested issues, the role and scope of the Supreme Court, who was qualified to vote, how to count slaves, the privileges and entitlements that accrued to a “citizen” remained unclear for years after the Civil War.

Lepore provides ample discussion of the emergence of Jim Crow laws after Reconstruction, the emergence of the Gilded Age and the reforms that comprised the progressive era. There are conceptual discussions of the relationships between populism, progressiveness and liberalism, which clearly have their application to the present moment. She discusses at length Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal liberalism (and the exclusions of Blacks from many of its programs) as well as the emergence of conservative reactions that brought together businessmen with rural Americans who resisted government intervention in their lives.

Always interested in the influence of science and technology, Lepore gives emphasis to the role of polling, introduced in the 1930s, and how, in her analysis, it has served to skew the electorate and how polls have often proved woefully inaccurate. Perhaps presaging the coming of social media in molding opinion, Lepore provides fascinating discussion of the role played by radio and debates over its influence. It boosted evangelical religion by providing an outlet for radio preachers. Not only did millions tune into FDR's fireside chats, but huge numbers were influenced by the the anti-New Deal and antisemitic diatribes of Father Charles Coughlin.

The Second World War, the post-War growth of the middle class, the McCarthy years and the Cold War and the Civil Rights eras, including internal divisions, all get ample treatment. The author is also equally keen in discussing more recent trends: the New Left, the Vietnam War, Nixon and Watergate. It is here that she sees the emergence of cynicism about truth itself, an epistemic tendency that has transmogrified to a degree that threatens democracy and societal cohesion to their core.

There is the rise of modern conservatism, in great measure a response to New Deal liberalism and the expansive role of government. Reaching its apogee in the laissez-faire, trickle down economics of Ronald Reagan, she finds contemporary judicial trends in the emergence of originalism adopted by conservative members of the Supreme Court, in response to the privacy rights enunciated in the Griswald case, allowing for the sale of contraception, and Roe v. Wade.

Lepore is again prescient in her treatment of identity politics, especially in its currents manifestations. She notes:

"By the 1980s, influenced by the psychology and popular culture of trauma, the Left had abandoned solidarity across difference in favor of the meditation on and expression of suffering, a politics of feeling and resentment, of self and sensitivity. The Right, if it didn't describe itself as engaging in identity politics, adopted the same model: the NRA, notably, cultivated the resentments and grievances of white men, feeding in particular, both longstanding resentment of African-Americans and newly repurposed resentment of immigrants. Together both Left and Right adopted a politics and a cultural style animated by indictment and indignation."

Jill Lepore ends her long narrative shortly after the election of Donald Trump. She ends a trifle too early to take in the full ravages of Trump's destructive rampages, but clearly sees what is at stake:

"The election had nearly rent the nation in two. It had stoked fears, incited hatreds, and sown doubts about American leadership in the world and about the future of democracy itself. But remorse would wait for another day. And so would a remedy."

Indeed.

Jill Lepore's These Truths is an extraordinary achievement. In a single volume it incorporates political and social history, “great men” and lesser knowns who deserve recognition. It provides statistics (never excessively) photographs and wonderful, engaging, anecdotes to illustrate points that might otherwise be dry. But most of all, Jill Lepore is a realist. There is little vaunted heroism here: The figures are all recognizably human. Above all else Jill Lepore's America is a complex story of contradictions and conflict, a nation that forever seeks to remake and define itself. The American narrative, our America, remains open and unfinished.

This is a history of America we all need and need now.

MORE RECOMMENDATIONS & READER RESPONSES

Historical Fiction Done Well: Not for the Faint at Heart: Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez Reviewed by Phyllis Wilson Moore

Reading the novel Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez is a deep descent into an ugly world at an ugly time, the depression-era world of the 1930s in a small segregated Texas oil field town. It is a fictional account of a true school disaster and the author is equal to the task.

The town is all too familiar to many of us: over the top racism, abuse, poverty, trauma. Immigrants and persons of color with no rights or protection. Rich is good. White is right. Women are subservient.

A man's home is his castle. Control belongs to "the man" and justice is truly blindfolded. We know this story all too well. It is an American tale.

This is a grinding and gritty novel, but beneath all the debris is a story of love: familial love, love of country, romantic love, love of education.

Some may consider it an unsavory story. There are huge chunks of nastiness: dangerous labor practices, poverty, racisim, bullying, rampant and rabid discrimination, rape, arson, wife abuse, sexual abuse, child abuse, murders. And there are families. Good and not so good families. Families that stick together and families that do not.

When the town's elaborate new school, filled to the brim with white students and teachers, explodes, grief is soon followed by scapegoating. And we Americans often know where to find scapegoats. In this case, a beautiful half Mexican teenager is fair game, as is her best and only friend, an intelligent college-bound Black boy.

I cannot unsee the scenes or unfeel the emotions this author unearths throughout this novel, especially in the final chapters; she is that good. One of her strengths is showing childhood traumas and their lasting effects. The ending, told through the eyes of a now-grown survivor, is drop-dead perfect.

It is my understanding the novel is under fire in some school districts as being unsuitable for students.

Personally, I would not assign OR withhold this historical novel from any reader. Based on my own experience, readers find what they need to read. I found OUT OF DARKNESS. So can you.

.

Caped Crusaders 101: Composition Through Comic Books by Jeffrey Kahan recommended by Peggy Backman

A scholar teaches composition via story structure and other compositional strategies in comix.

Shakespeare in a Divided America by James Shapiro recommended by Daniel Gover

Daniel Gover writes: "I'm glad you liked James Shapiro's book on King Lear. I really enjoyed his book Shakespeare in a Divided America inspired by a Shakespeare in the Park production of Julius Caesar in which Caesar was played as Donald Trump. [Shapiro] goes through American history looking at times when Shakespeare became controversial for Americans, like during the Mexican War of 1848 when a young army officer Ulysses Grant was cast to play Desdemona in an US Army production of Othello. It's a great read for Americans who love Shakespeare.

Danny Williams writes, "Fish and babies, we need to know length and weight. And also name, in the case of babies."