Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 214

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

May 10, 2021

John

le Carré Oyinkan Braithwaite

Brit Bennett Helen Weinzweig Marilynne Robinson

Hamilton Stone Review #44 Is Now Available!

Poetry: Carolyn Adams, Dan Alter, Tony Beyer, Sharon Black, Michael Carrino, R.T. Castleberry, Patrick R. Connelly, William Doreski, E.J. Evans, Howie Good, Nels Hanson, Katrina Hays, Leonore Hildebrandt, Joseph Kerschbaum, Michael Lauchlan, Rebecca Ledbetter, Harriet Levin Millan, Emmett Lewis, DS Maolalai, Gordon W. Mennenga, Daniel Edward Moore, Philip Newton, Roger Pfingston, Meggie Royer, Gerard Sarnat, Claire Scott, Barry Seiler, J.R. Solonche, Shelby Stephenson, Phillip Sterling, D. E. Steward, Tim Suermondt, Michael Walker, Erin Wilson, Marie Gray Wise, Pui Ying Wong, Mark Young.

Prose: Dan A. Cardoza, Kathie Giorgio, Lisa Lebduska, Harriet Levin Millan, Babak Movahed, Heather Whited.

Do It Yourself MFA--

Check it out!

These crack me up: Fifty-very-bad-book-covers-for-literary-classics/

On Marilynne Robinson and Elena Ferrante by John Loonam

Notes on Philip Roth by Carole Rosenthal

Book Reviews

Spy, Detective & Fantasy Fiction

Announcements

Things to Read Online

Irene Weinberger Books

Ernie Brill's Reading Lists

For Expanding the Canon:

International top-notch short novels less than 200 pages

International Woman 's Literature

Book Reviews & Commentary Alphabetical by Author:

Two by Brit Bennett:

The Mothers and The Vanishing Half

My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

The Black Echo by Michael Connelly

Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens

The Assassin's Apprentice by Robin Hobb

Royal Assassin by Robin Hobb

Quinn's Book by William Kennedy

The Chill by Ross MacDonald

The Perfect Spy by John Le Carré

Death at La Fenice by Donna Leon

On Marilynne Robinson and Elena Ferrante by John Loonam

The Common Good by Robert B. Reich

Notes on Philip Roth by Carole Rosenthal

Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood by Fatima Shaik

Smalltime by Russell Shorto Reviewed by Peggy Backman

Basic Black With Pearls by Helen Weinzweig

The Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar

This spring I had a large novel writing class (by Zoom) and a lot of pages to critique. So for my personal reading, I've been doing mostly genre, including some rereading, I did, however, read my first John Le Carré and the magnificent The Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar. I also read a couple of recent books: two by the young, excellent, best-selling Brit Bennett. Her work also strikes me as another good place for cisgender and white people to learn a little something about human variety.

This issue also has some very interesting remarks on Philip Roth by Carole Rosenthal as well as John Loonam's excellent piece on Marilynne Robinson and Elena Ferrante. It also has my review of a nonfiction book about the gens de couleur of New Orleans in the nineteenth century and later..

If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW.

REVIEWS

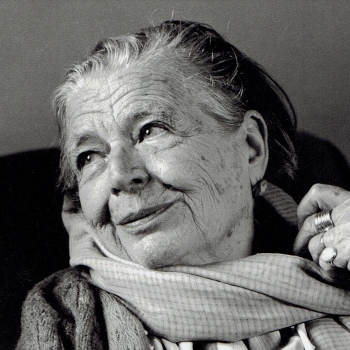

The Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar

How did I miss reading Marguerite Yourcenar's The Memoirs of Hadrian? What would I have made of it when I was twenty-five or thirty? I would have recognized the value when I was young, but it wouldn't have involved me emotionally as much.

Yourcenar wrote it over more than ten years, insisting that her early accumulation of material could never have resulted in a book without the passage of time. Of course, she also said she had all her ideas for projects in mind by the time she was twenty, and the rest was just finalizing. This is probably the best novel I've read written in the nineteen-fifties, and it may turn out to be a favorite of my old age. There is something so appealing about experiencing the life review of this character from two thousand years ago, seeing him struggle with who he is, what he has achieved, where he has failed. His enthusiasm for his administrative work as an emperor is only equalled by his love for a boy (which is what I vaguely always thought the book was about). The insight into pagan religion is interesting too, especially his distaste for the religiously exclusive (and rebellious) Jews whose insurrection he puts down viciously.

It's a wonderful book, translated from the French by Yourcenar's partner Grace Flick. They sat across from each other with their typewriters.

I look forward to reading it again.

For more commentary, see:

"Becoming the Emperor" in The New Yorker and "What Marguerite Yourcenar Knew" in The New York Times.

The Mothers by Brit Bennett

My new favorite very young novelist is Brit Bennett. She was born around 1990 and has two best selling novels so far, The Mothers, and The Vanishing Half. The Mothers is set in California, and a lot of the plot centers around a church called the Upper Room and

two young women whose mothers failed them, one with a mysterious suicide, the other by letting her boyfriend make the trip down to the girl's bedroom.

A boy they both love, a spoiled preacher's son, is a football star who suffers sports injuries, beatings, general laziness, and a controlling mother. He's not very likable, even though Bennett goes to some trouble to explain him.

The most powerful character is Nadia, the suicide's daughter, who tries to get away from her past, and in some ways does. She is tough, smart, drawn back by her father's wounds, by her love for Luke and Aubrey. The extra touch to the novel, which I think Bennett probably loves more than I do, is the "Mothers" themselves, the women elders of the church, widows or otherwise manless, commenting on the action and characters, equal parts wise and foolish.

The real heart of it is Nadia and her loss of her mother, her abortion, her love for the frequently clueless Luke, her friendship with Aubrey.

For another view: New York Times review of The Mothers

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

I read this, Bennett's second book first. It's very much of this contemporary time with its subject matter of race and gender fluidity. The premise is that one twin, a woman who looks white, passes and disappears from her sister's and mother's lives. The other sister, who also looks white, comes home with a dark skinned little daughter, who is teased, ignored, and brutalized for years by her "black" but very light-skinned schoolmates. Their small town has the interesting property of being entirely populated by African-Americans of extremely light skin color. The little girl grows up, gets a scholarship to college, goes on to become a doctor, falls in love with a trans man, and they make an eccentric but loving life together.

Actually, the whole novel is full of varied and interesting couples. It's supposed to be set in the nineteen-sixties, seventies, and eighties, but feels earlier, maybe out of time. The vanished sister turns out to be leading a life that is a painfully stereotyped world of quietly racist white suburbanites. Except for those affluent stereotypes, Bennett creates a kind and loving book. If it's a little hard on white people, well-- what the heck--we usually deserve it.

Friendship and Solitude in Elena Ferrante and Marilynne Robinson by John P. Loonam

A friend recently suggested that Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels represent the masterpiece of the century so far. It takes nothing away from Ferrante to suggest that Marilyn Robinson’s Gilead Novels offer stiff competition. The story of two ministers and their families in the fictional town of Gilead, Iowa in the late 1950s, these novels take a hard yet lyrical look at some major questions – right and wrong, love and desire, the nature of faith, the relationship of pride and shame, the balance between individual agency and community obligation. While the characters are of varying levels of education and experience, they are collectively an amazingly articulate family of heady thinkers.

Jack, published last year, is the fourth in the series (Gilead [2004], Home [2008], and Lila [2014] are the others). Jack tells the back story of Jack Ames Boughton, son of one of the ministers back in Gilead, namesake of the other. Readers of the series already know a great deal about Jack: He is the prodigal son of the Boughton family, having left home years earlier after a youth and young adulthood that brought constant tension and shame to his family. He has, seemingly from birth, been a petty thief and a liar. As a young man, he seduced and impregnated a local girl, then abandoned her and their child. We also know that, after years away from home, he will return to Gilead broke and jobless, separated from the African American woman who is the mother of their son. The family has had to flee St. Louis to avoid scandal and prison because mixed-race marriage is illegal in both Missouri and Iowa. We know that Jack waits for some weeks in Gilead, then leaves just days before Della arrives with their child, leaving them again lost and homeless. In this novel, we see the dawn and maturation of this

spiritual marriage, and track its effect on Jack.

Jack Boughton is no ordinary reprobate. His stealing is of a kind of compulsion that fuels his internal debate about the nature of sin, crime, agency and predetermination. This debate within his head gets so complex and heated that taking the opportunity to steal is the only way out. His drinking is driven by a complex cycle of shame. He has recently been released from prison and is living in a shady boarding house off money made from odd jobs and left for him at by his brother, who he refuses to see. Jack refers to himself as the Prince of Darkness and is convinced he brings both moral and practical harm to those around him.

However, one day while wearing a good suit (purchased with funds his brother gave him so he might attend his mother’s funeral, which he does not) he helps Della Miles retrieve some papers that have blown from her bag as she walks home from her job as a high school English teacher in a rain storm. He walks her home under the protection of an umbrella he stole earlier in the day and the two feel an immediate and powerful connection and attraction. This gives Jack the idea that the suit is a kind of false advertising – Della has mistaken him for a minister – and he trades it in for rattier clothing to avoid giving people a false impression of decency.

Shortly after this, they meet and spend the night in a graveyard. Jack is there to sleep because he sometimes makes extra money by subletting his room for the night. Della is there to see the monuments because Jack has praised them during their brief conversation, but has accidentally been locked in for the night. It is an all-white graveyard and the shame of being caught might cost Della her job. So might the shame of spending the night there with Jack, but they have a long, remarkable conversation about sin and redemption, spending some time imagining that they are the last two people on earth and can make new rules for behavior, can in effect redefine sin. The issue of race hangs over every moment of this encounter, but only by implication. They never clearly state that Jim Crow is the source of danger for Della and the reason their relationship is impossible. In this world, segregation is as accepted as, and far less remarked upon than the weather

One of the curious aspects of Jack, and of the entire series of novels, is that they present a deeply detailed and nuanced examination of the world these characters live in without any evidence that anyone is really paying critical attention to that world. Though the novel is set at the dawn of the Civil Rights movement, there is no real hint that such change is possible. Jack spends a good deal of time reading the papers, but we hear very little about the news they contain – just that a series of urban renewal projects is poised to decimate Black neighborhoods in St. Louis and that there is little anyone can do about it. This is a world without the concepts of protest, civic action or social change.

Racial attitudes are entrenched all around. Della’s family disapproves of her relationship with Jack not because he is a broke ex-con with no job prospects and a serious drinking habit, but because he is white. In the years that Martin Luther King is making the case for integration, Robinson turns back half a century, presenting a family of morally rigid black separatists who live quite consciously in the tradition of Marcus Garvey. Jack is thrown out of one very nice rooming house when the landlord finds out he is involved with a Black woman. There is a tense scene involving a segregated bus trip, with no reference to the injustice of the segregation or the ongoing fight against such segregation. Jack and Della imagine a world without rules, with the rules preventing their relationship being the first to go, make attempts to see each other surreptitiously, and ultimately defy the racial norms, but no one ever discusses any attempt to change those norms.

It is obvious that this is not because Robinson either approves of these laws or is unaware of civil rights history. She presents segregation as a part of the world order and then examines that context of injustice in her characters’ moral decision making. Robinson’s view of morality, her theology if you will, centers on the human connections that give us both the responsibility and the obligation to care for one another. It is, in these books, inherently individualistic – not in a right-wing, selfish way, but in a kind of Calvinist, personal responsibility vein.

Jack’s thinking around the morality of his relationship to Della centers on his capacity to hurt her. While he senses immediately – while still holding the umbrella over her head – that she gives him an acceptance and comfort he has never felt before, he also understands (and is repeatedly told) that being with him will cost her dearly. He accepts the notion that his love for her might best be expressed by leaving her alone. He also understands that she feels a similar acceptance and comfort around him and that leaving her will cost her perhaps just as dearly. This then becomes the moral dilemma the novel centers on. Jack, who sees himself as a permanent, innate source of harm to others and himself, is faced with the opportunity to do someone some good, if he is willing to make a choice.

All of the advice Jack receives – from Della’s minster father, from a Baptist minister he seeks out for advice and from the hostility of the white world, tells him to leave. His understanding of the cost to Della is tempered by his own desire to stay, which he interprets as selfishness. Since his involvement with Della he has found jobs, given up drinking and begun to think of himself as belonging in society. He sometimes imagines that he will honor the sacrifice they have to make through separation by continuing to live a productive, appropriate life, but the reader suspects he will drift headlong into dissolution. For Robinson, love is not a simple or easy solution to loneliness or shame, but it is the only solution – there is no sense that politics or social change will let us off the hook.

In Ferrante’s novels, friendship acts as the sandpaper we hone our selves with. Lena cannot be Lena without her friendship with Lila, though for much of the four novels that brilliant and sharp-edge friend is seen as limiting her, cutting into her own desire for expansion. Ferrante’s great achievement is to examine the formation of a self over the course of a single character’s lifetime and a single friendship. That friendship constantly pulls Lena back to Naples, to her own roots, to that moment when her world opened up and Lila’s closed a little. Lila is a source of both liberation and limitation and, indeed, there are times when it is hard to tell the difference.

Robinson’s world view has similarities in that the world is inherently limiting and destructive – force no one can stand up to alone. Jack certainly can’t, and we see that Della’s proud position of status is, in her own eyes, empty and stultifying. The other novels are less drastic in their sense of danger, but certainly Ames could not have been himself without his friendship to Boughton and it is his inability to accept Boughton’s relationship to Jack that prevents the fullest flowering of that friendship. Glory must return home to understand her individuality and Lila must come to accept that she is John’s spiritual wife, that he is not just shelter from her stormy past. Not only can people offer each other a way to be themselves, but there is no way to achieve that selfhood alone – the world is simply too cruel. We must love one another or spiritually die.

Notes on Philip Roth by Carole Rosenthal

These notes are in response to an interesting article in Bookforum by Christian Lorentzen.

I am not a fan of this Lorentzen article, though it is [one] take on a man and his life. I am a huge fan of Phillip Roth and agree with the notion that he was possibly the great novelist of his generation and I think he should have won a Nobel Prize and didn't for primarily political reasons--one of which is that he was Jewish and not incidentally so, yet secular. (This counts internationally.) He engaged with Jewish issues and opinions about Israel, vastly increased the readership and critical attention of previously overlooked Eastern European writers, and was in many important ways a public intellectual.

All of of his books are not equally good. I liked Nemesis, for instance, which [Lorentzen] did not and it turns out Lorentzen once wrote a negative review that he calls our attention to in the article (careerist intentions Lorentzen?) Mostly I reject this thesis that Roth is/was a careerist.

So what? He had an 'exquisitely managed career?' Good for him. Let me recommend Claudia Roth Pierpont's more nuanced but much longer critical work, the book Roth Unbound, in which she discusses Roth as a moralist. Which I find him to be. Yes, he was a misogynist, a man of his times with that time's limitations, and his women characters can be treated in stereotypical and even ugly ways (Melanie, the daughter, in American Pastoral, comes immediately to mind here). This is awful, but I, a woman and and a feminist, get that. But I am also the same Jewish woman who read Oliver Twist wherein Fagin, the villain is usually referred to and on many many, many pages, far more often as The Jew than by his name. Apparently I have a high tolerance for this if the work has depth, fine writing, and philosophical impact. I love Flannery O'Connor, a casual racist in her usual take-it-for-granted way. In fact, Roth, Dickens, and O'Connor are three of my favorite authors. This gets me into trouble (in teaching, it got me into unbearable trouble when I taught Oliver Twist, and I don't think I would ever do that again because I hadn't realized how totally saturated in virulent yet routine antisemitism that book is). But still. A great writer and a moral writer who is willing to engage in important questions is rare. And with this kind of writer one can--me, for instance---disagree.

I do think Lorentzen shows his respect, but he is too dismissive of 'the life' and the subject matter, reductive. Roth was a man with problems in his personal life and that--artists constantly circle their problems-- was part of the impetus for exploring his subjects; Roth's emphasis on sex often stands in for the larger problems in human relationships. He wrote about family too, and discrepant social and political issues, about parent-child relationships, and he was not good with children, and less than perfect on race, for sure. But I don't judge a writer by his life or even his life in his writing (Celine is a bit difficult for me though).

Nor do I believe that any artist should be judged by his life or even the mystique of that life, if I can avoid it and it doesn't make me pull my hair out or turn away. There is a great difference between a [hu]man life and the art created from it....Roth was flawed in some important ways, yet I think it behooves a fine writer to 'manage' his career....yet I have noticed again and again in many great artists that there is a level of ruthlessness required, maybe even necessary. Not all. I think of Grace Paley who I also love, not a great manager of her career. And not enough works in print therefore, the same for Tillie Olsen. Dickens, on the other hand, well Dickens and Dostoevsky and Lawrence, they all wrote and 'managed' and published a lot. I loved Roth's sense of humor, his marvelous, marvelous writing of sentences and deep understanding of so many ideas, his fundamental integrity as a writer. Some of his work is downright awful, but that is the risk one takes. His later novels do drop off, but not all, and we might disagree about which ones. Anyway, Lorentzen's is an interesting take, but certainly not a definitive one.

More articles on Roth:

https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/8035/not-a-nice-boy/

https://www.bookforum.com/print/2801/the-life-of-philip-roth-and-the-art-of-literary-survival-24390

Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood by Fatima Shaik

This fascinating book is a history of an institution that most 21st century Americans have never heard of.

Fatima Shaik, novelist, journalist, and native of New Orleans, found her material in rediscovered journals, minutes of meetings, and other documents--

materials her own father saved from destruction and passed on to her.

Economy Hall was built by a benevolent society of free black men in New Orleans, many of them of Haitian descent, so the language of most of the documents is French. It is the story of men striving to uplift each other and their families and other people by creating a place for dignity and equality. They eventually build a splendid hall/community center for their activities and to rent to other organizations of the community of color.

The long time secretary of the organization, Ludger Bouguille, and his family, are central to Shaik's story. He was a teacher of generations of New Orleans children of color, and his meticulous minutes of meetings give great insight into the thinking and joys and sorrows of the brotherhood.

Many of the original members fought in the Battle of New Orleans and helped create the American state of Louisiana. They were professionals and highly regarded craftspeople. You had to go through an application process to join, and there were solemn secret ceremonies and elaborate celebrations. The book is a broad exploration of the nineteenth century world of literate, free, gens de couleur.

The Civil War marks a turning point for this community as for many others. Many of the men fought for the North (New Orleans came back under Union rule early on), and the following years of Reconstruction gave great opportunities for these professional men to be involved in city, state, and even national politics and leadership. They supported, with considerable success, racial equality--until the disastrous return to white supremacist rule through much of the South in the late 1870's. After the resurgence of the white ruling class, along with its associated voter suppression and Jim Crow laws, the story becomes grim and familiar: riots and lynching, and the gradual pulling back of the men of Economy Hall from their activism for racial equality. Economy Hall becomes more and more a sort of apolitical community center.

The final chapter relates its importance as an incubator for New Orleans jazz community, which gives a definite uplift to the history, but cannot–can never–hide the horrors of the violence of white supremacy and the roll-back of political freedom at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

For more on this book, read Diane Simmons' review in Good Reads and the New York Times review (scroll down to find it).

Quinn's Book by William Kennedy

This is one of those books I feel I should like more than I do. I was a big fan of Kennedy's Ironweed and, in fact, used to teach it as a model novel. This one I admired but had no trouble leaving alone for a while. Everything the blurbs and reviews said was more or less true, although I'm not so convinced of its large-mindedness and generosity. It's more tart than that.

Set in Albany from the 1850's through the Civil War, it manages to include anti-Irish violence, the race riots in NYC perpetrated largely by the poor Irish, and Civil War battles, as well as lots of nineteenth century performance hokum and one-on-one violence.

Daniel Quinn, our narrator, is a young orphan who becomes a newspaper man (as, I discovered, was William Kennedy). Lots of vague supernatural stuff is at once pervasive and peripheral. And it's a love story.

It's a quirky but interesting example of historical fiction (another from my book of novels chosen by historians- Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other) compiled and edited by Mark C. Carnes.

Quinn's Book is a good read, but not as profound as the blurbers would have you believe.

Smalltime by Russell Shorto Reviewed by Peggy Backman

Peggy Backman, who grew up in Johnstown, Pennsylvania writes: "Just finished reading a new book called Smalltime by Russell Shorto. You might find it interesting, although I don't think it's as well done as it could've been. I heard he was a very good writer but this is the second book I've read recently that is sort of an historical narrative, but just doesn't work the way it's done.

"That said, I found the information in the book quite interesting, as I recognized a lot of places in Johnstown [PA], which is where it takes place. It's basically about the mafia in small-town America, with a focus on Johnstown. I had no idea how big of a deal it was there, and a lot of the book takes place during the period when I was around.

"I do remember going with my parents to a fancy restaurant, Shangri-La, when I was probably in elementary school. I think someone took us there but I don't remember who it was. To keep me busy I was given a bunch of dimes or quarters and told to go play the slot machines. I was also told to keep a low profile, as children weren't supposed to be playing them. The fact is nobody should've been playing them, as they were outlawed in Pennsylvania. That of course is tip-off re: who owned the joint. In any case I was trying to be a good kid but hit the jackpot and out came oodles and oodles of noisy coins accompanied by flashing lights My joy at winning was overshadowed by the fact that I had been told not to draw attention to myself. So it goes.

"I remember trying to coax my parents to go back there again, because I thought the restaurant was so nice and fancy. I think they were reluctant to do so, partly for fear of being there when there might be a raid."

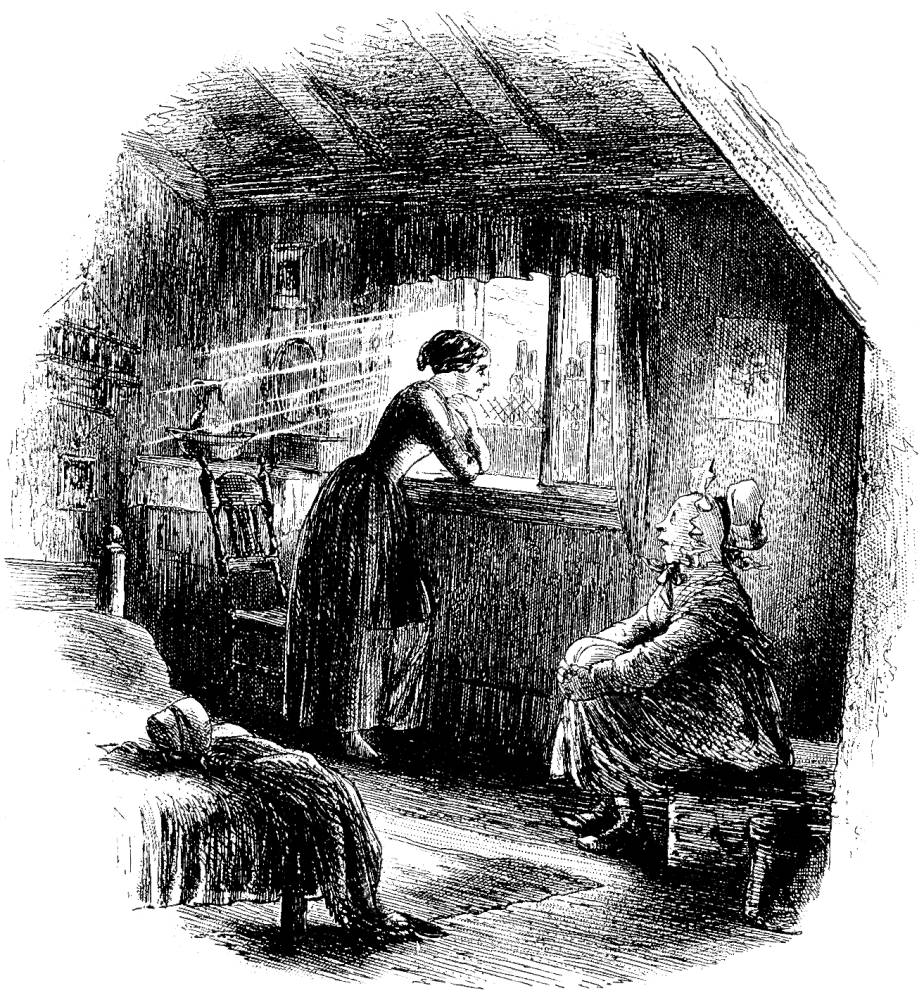

Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens

Little Dorrit telling a story to Maggie in her room overlooking the yard of the Marshalsea debtors' prison.

800 plus wonderful pages of mature Dickens: his last book published in serial form, with all his strengths of vivid language and metaphor, and most especially his splendid characters, usually just this affectionate side of caricature--like Mr. Panck the little tug boat steamer of a man who snorts and runs his fingers through his hair constantly raising it into spikes. There are secrets and melodrama to spare, and the eponymous heroine who is so good and so little and so unbelievable..

Dickens had a terrible real-life history of relationships to girl-women who don't stay small and innocent in real life, so he creates idealized heroines who are ridiculous but somehow still touching. Little Dorrit, born in the Marshalsea Debtors' prison (where Dickens' own father spent some time), cares for her father ("Father of the Marshalsea") and her brother and sister and a host of other people, keeping them fed and clothed. She also supports their ill-deserved pretensions to gentility.

One improvement here is that Little D. is that she falls in love, and everyone knows it except her beloved. She also moves around the city of London with alacrity and freedom–so she is stronger that everyone thinks she is. The the male lead, Arthur Clennam, proves to be almost as self-effacing and self-defeating as Little D, and is less interesting to this reader, anyhow, than everyone around him. There is also an operatically masterful and ridiculous villain who, yes, twirls his moustache. Then there's Mrs. Clennam, one of Dickens's tortured evil-doing mothers, And little John Chivery the writer of his own epitaphs, which decorate the novel throughout

They are all wonderful, and the city is wonderful, and the dark, dismal, tumbledown House of Clennam is wonderful, and of course above all, Ye Olde Marshalsea Prison.

The miracle is, as always, how Dickens managed to create a world so utterly unlike this world, that is at the same time so meaningful to this world. Highly recommended if you're in the mood for Dickens. But feel free to skip the long boring satiric chapters on the Barnacle family at the Circumlocution Office.

The Common Good by Robert B. Reich

This is not my kind of book–I like Robert Reich in small does, especially his little youtubes where he explains some political or economic point with clear words and little line drawings.

But for me, this is an example of one big idea with a lot of padding. Where's the nuance? Where's the deep insight? I agree, of course, that the U.S. Is rapidly losing, at least since Reagan and maybe since the late sixties, a sense of a common good.

Reich's points are right-on: honorary degrees to corporate thieves, corporations that only take responsibility for maximizing stockholder profits (Reich says there was a time when public good was considered part of their responsibility–not sure I believe it, but that's maybe my cynical sixties self speaking). Lots of examples, the distinction between private and public morality: lots of good stuff, but maybe better as an article or as the outline of a talk.

My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

This is a novel that has a light tone and shockingly heavy events: the big sister sticks by her psychopath younger sister in spite of what she, the younger sister, does–and no spoiler alert, the title says it all as do the first two sentences.

So she sticks by her sister in spite of jealousy of the younger one's great beauty and lack of anything resembling a moral compass

The Narrator's moral compass, on the other hand, is quite clear: I take care of my sister. Anyhow, it's short, funny in a deep way–I think the comedy comes from how it plays out its premise and makes you identify with the narrator in spite of her clear but twisted moral universe. A story of strong values, just not mine and likely not yours. I hope.

SPIES & DETECTIVES & MAGIC, OH MY!

The Perfect Spy by John le CarréThis was my first Le Carré. I had a lot of trouble getting into it: the way Pym talks sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third person, sometimes to his son, sometimes to Jack Brotherhood (great name). But once I got the rhythm of it, I was all in. I especially enjoyed all the parts about Pym's con-man father, who

mesmerizes people with his charm and gets all kinds of free services and goods and rips off everyone in sight. Pym as a little kid is part of the high jinks and high energy, and the friendly, funny gang of thieves, who take a certain kind of good care of him. The double talk and tricks and capers prepare him to be the perfect spy.

Early in his career he betrays his friend Axel. There's a reversal between them later, and also a continuing deep mutual affection. I don't have a lot of tolerance for gamesmanship and convoluted plot qua plot, but the actual spying is treated as of far less interest than a cynical world view and, of course, Pym's determination to get out of it.

The finale comes on us gradually as Pym's handlers slowly close in on him after his escape. It has really good momentum. Pym makes increasingly frantic preparations to finish off his business, and almost to my surprise, I was very moved at the end.

Death at La Fenice by Donna Leon

A reread of the first Commisario Brunetti book– it felt slower but more carefully worked than the later ones. It doesn't have Guido's good policeman companions, but does have wife, in-laws, kids, and oh yest Patta, the Sicilian boss at the police station.

I loved most Venice and the eating and drinking (a lot of wine goes down). Perhaps a better planned plot that some of the later ones. Later, she seems to care less about the plot, but always about Brunetti and his family, and Brunetti's determination, and his not always-quite-lawful approach to justice (not vigilante justice, but something along the continuum in that direction).

The Chill by Ross MacDonald

Praised in someone's list as a classic murder mystery, The Chill has a nice twist–the perp turns out to be someone we've seen from early on, but Lew Archer is a cipher, a machine for asking questions. It was also heavy with nineteen-fifties-sixties Freudian psychology and an assumption everyone agreed about Freudian interpretations that we seem to have rejected today.

What changed? One thing was second- wave feminism. Another was ethnic/racial awareness. We still accept deep reasons, the importance of what was done to us in our childhoods, so psychology isn't gone, only Freudian psychology and, oh boy, I'm thankful to have out-lived penis envy as an explanation! Along with garter belts and seams in your nylons.

But if Lew Archer had been more interesting, not just an inquiring voice, I would have accepted all that more easily as of its time.

The Black Echo by Michael Connelly

This is the first Harry Bosch book, and a reread for me. It has J. Edgar more interested in real estate than work,

but still with Harry's back; it has Eleanor Wish, who ends up in jail. It also sets up the Harry's traumatic Vietnam service, in particular the tunnels, and there is a tunnel bank heist and a tunnel-like pipe with a corpse. This is one area in particular that the TV Bosch falls down on: making him an Iraq vet just doesn't have as much resonance for Harry as a character. Maybe the best books in the series are these early ones, up through Angel's Flight, or do I just like that one because I've ridden the little funicular in L.A.?

Bosch's sex life is unusually well nuanced: he is described as not performing very well the first time he has sex with Eleanor--he's had a long sexless hiatus, but he takes a rest and gets his game on. But it's tender and believable. He's such a neurotic, and so focused on the one thing he's good at, which is solving murders.

Anyhow, the reread was better than the first time round. Very careful writing (some of the later ones more perfunctory, as if Connelly is barely showing up. Like Donna Leon? More like Elmore Leonard, doing little more than a treatment, some scenes and dialog.

I just looked up in my journals when I started reading Connelly's Bosch books. I began in 2017, part of the Kindle genre-fest while we were buying and selling houses and moving. They helped get me through the stressful time.

The Assassin's Apprentice and Royal Assassin by Robin Hobb

Narrator FitzChivalry Farseer is, on this re-read, still a little too whiny for my taste, but the story is a galloping good read. It was interesting the way scenes came back to me as I read. I love a lot of her concepts, like

"the Wit," which is a human-animal communication and connection that people are denigrated (and worse) for acting on. Lots of intrigue and poisoning. I like the spying stuff, still find the Fool good in this book, although I think Hobb loses control of him/it/her in later books.

I find it easier to critique, or maybe study Hobb's work than, say, George R.R. Martin's, but Hobb wins on gripping, complicated ethical dilemmas

I also read Royal Assassin for the second time. I think I enjoyed it, too, more on this second reading. The first time I read too fast, just gobbled. This time I got the story and accepted the magic parts much easier, but also got irritated with the Fitz again and his attitude, though not his actions. The final book, which I haven't re-read and remember as having a quest I didn't like much in which a lot of dragons statues came alive. Maybe it will be better too!

I sound pretty whiny myself, as if I weren't enjoying these hugely: Hobb is really really good. Good food. Good smells. Excellent villainous Prince Regal. Brilliant deeply-animal Nighteyes the wolf.

Basic Black With Pearls by Helen Weinzweig

Worthwhile read. It isn't my favorite set-up-- a neurotic woman whose life centers around a love affair. She wanders the world (or her room or her past) observing, sensing, despairing, hoping, observing some more. She has brief interactions with strangers. As a life style, it offends me for its lack of accomplishment and action! Over the years, I have read older versions of this type of book (I'm thinking of say the work of Jean Rhys and others who were proto-feminists in a time when feminism was more about sensibility than political action), but Weinzweig's book gathers energy and momentum.

It takes place in Toronto, which is the home city of the main character but also where the main character has her crisis and where she returns for a weird but strangely luminous evening with her estranged (ex?) husband, her children, and her husband's new wife or maybe concubine. He's a rigid maniac, but she gives up her secret agent lover (who made be fantasy or a psychotic illusion) and takes a new lover --maybe.

The book was published in 1980, when Publishers's Weekly said, "Celebrated in Canada as a feminist classic, Weinzweig's searing 1980 novel captures a woman's awakening to her lover's exploitation…. Weinzweig's prose style is sharp, particularly her dialogue: strange and surprising, it knocks every character interaction askew."

The New York Review of Books republished it in 2018 in its lost classics series.

THINGS TO READ ONLINE:

-- Marion Roach interviews Suzanne McConnell about her book on Kurt Vonnegut as a teacher,

-- A snarky and bracingly unpleasant critique of American fiction by Elif Batuman:: https://nplusonemag.com/issue-

4/essays/short-story-novel/

-- Hannah Brown's piece on Woody Allen and his penchant for young girls in Manhattan.

-- A story by Rachel King called "The Red Heads."

ANNOUNCEMENTS

-- Alison Hubbard 's' story "Belladonna" has won the prestigious Slippery Elm Literary Journal's prize for the short story. It will appear in the May 2021 print issue.

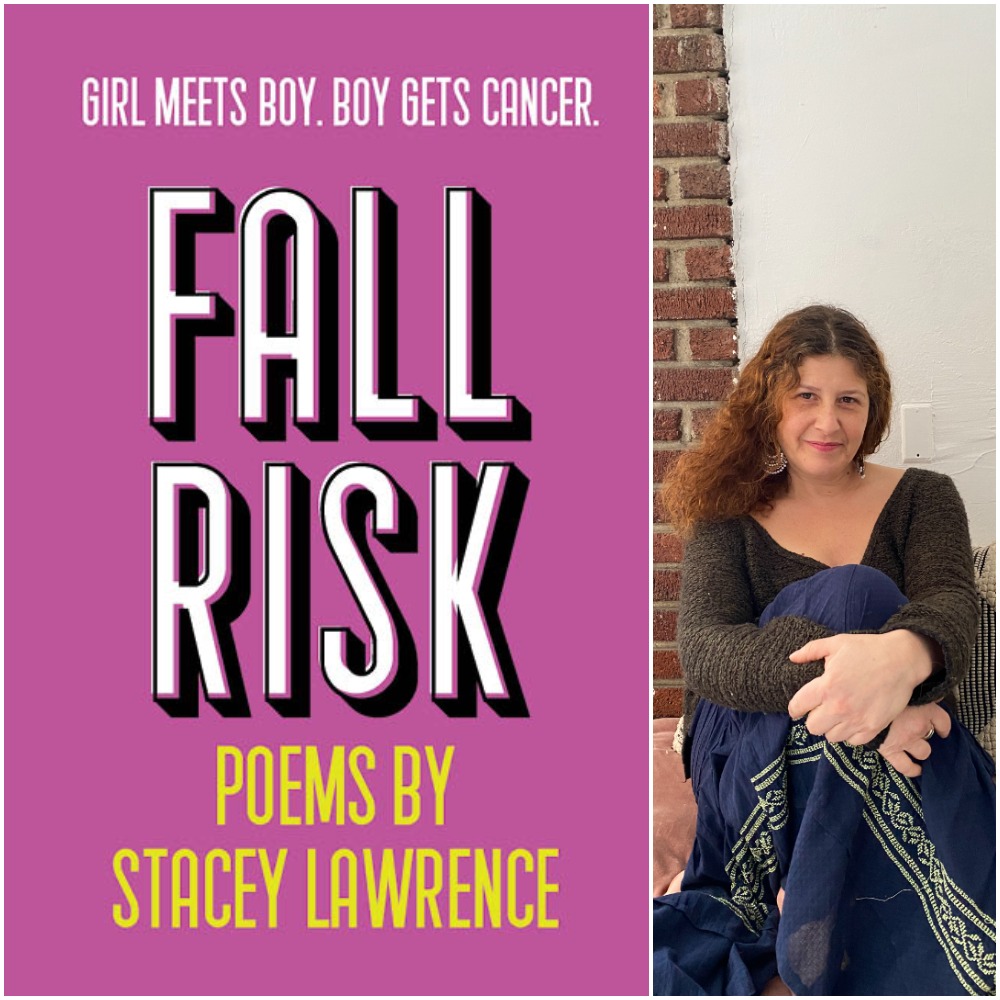

-- Stacey Lawrence's book of poems Fall Risk is just out from Finishing Line Press.

“It’s so seldom a book of poems can contain both love poems and acceptance of grief. Take Stacey’s poems to a couch, curl under your great-grandmother’s quilt, and understand love and loss are one.” –Nikki Giovanni“

-- A Quartet of Mysteries by Victor Depta

New from Blair Mountain Press

124 East Todd Street

Frankfort, Kentucky 40601

502-330-3707

victordepta1@gmail.com

bettyahuff2@gmailccom

www.blairmtp.net

Set in Hilly Kentucky and San Francisco

Involving College Professors, the Middle East, Devil Worship and an Asian Nursery

If ordered from Blair Mountain Press the discounted cost for the two is $15.00

The two volumes are also available, singly or as a pair, at amazon.com/books for the full cost

-- My Old Organization Teachers & Writers Collaborative Gets an Award from The Paris Review

In 2021, the Editorial Committee of The Paris Review elected to donate the $5,000 usually awarded to the winner of the Terry Southern Prize for Humor to an organization providing financial support to the writing community during a time when funds for the arts are in particularly short supply. The directors are proud to donate the $5,000 to Teachers and Writers Collaborative in New York.

"Teachers and Writers (T&W) is one of the longest-running and most respected organizations to provide arts education to children, by bringing professional writers into public school classrooms during the school day. To learn more about T&W leadership and programs, visit their website."

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 215

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

July 29, 2021

Book Reviews

Genre Line-Up

Readers Respond

Announcements! Stuff Happening!!

Things to Read Online

Irene Weinberger Books

ANNOUNCEMENTS:

— Kendra James' book Admissions: A Memoir of Surviving Boarding School

— An information-refurbished website to introduce you (if you don't already know her and her work) to Judith Moffett, poet and science fiction author: Judith Moffet.

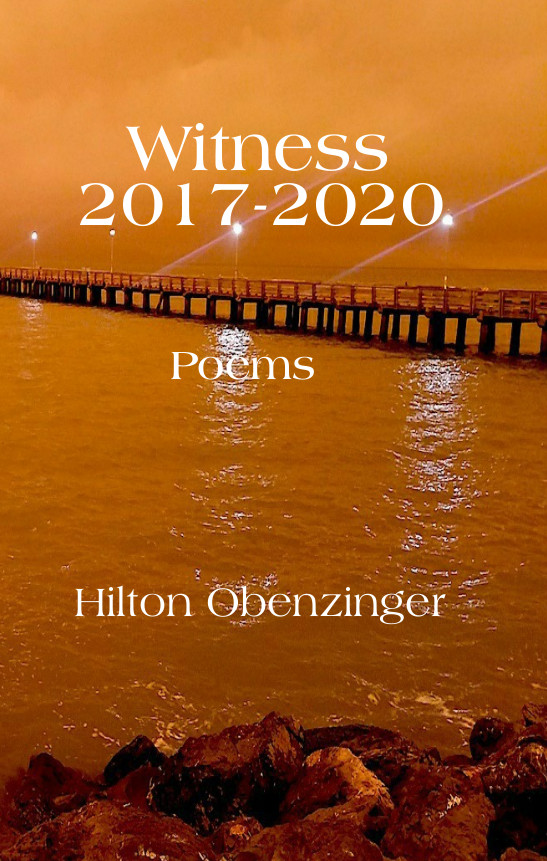

— Early review for Hilton Obenzinger's WITNESS in The Rag Blog. Jonah Raskin says, "The poems in Witness call for reader participation. In stunning ways, they offer a surrealist take on the news, and invite readers to make some news of their own. They’re also a kind of incantation meant to exorcise the unholy ghost of Donald Trump, whose name appears more than a dozen times in these pages — more than one might want— and to usher in a new era where all lives matter, where we all age with dignity and we all go into the future, no matter what it might bring. One doesn’t expect any the less from veterans of the Sixties who have gone on dreaming the dream and who have gone into the streets over and over again over the past five-decades."

—Rachel King's novel People Along the Sand is ready for pre-order. The book concerns the pleasures and limits of solitude for five distinct and deeply human characters, centered around the passing of the 1967 Beach Bill, the historic legislation that made all Oregon beaches public land. Kathleen Rooney says it "takes a lucid and discerning look at how people can belong to a place and whether or not a place can really belong to a person." You can buy it on Bookshop, Barnes and Noble, the evil but inevitable Amazon, or directly from your local bookstore.

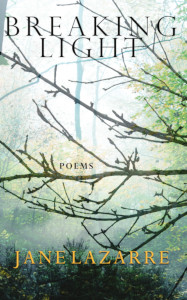

— Jane Lazarre's first book of poems "There is a formality in these pages, a reliance on structure to contain the powerful yet often restrained emotions. Light, nature, mourning and love provide a deep and familiar comfort and stimulation that remain long after we've stopped reading." From the Introduction, by Dr. Miryam Sivan

— Belinda Anderson's ALDERSON WV 2021 HISTORY BOOKLET Volume VIII is a a special edition of the "History Highlights and Tantalizing Tidbits" about Alderson, West Virginia. It has just been released by Alderson Main Street. This one commemorates Six Decades of West Virginia's Largest Fourth of July Celebration. The volume is not a traditional year-by year history but highlights the volunteers who make it all possible; some of the famous entertainers who have appeared; Queens; advertisers including "Red" Nickell; and much more. See Bookshop.

-- Miguel A. Ortiz has two new books!

See more of Miguel A. Ortiz's books at Irene Weinberger Books and at Hamilton Stone Editions.

— Tina Kelley's Breaking Barriers from Teachers College Press is about a transformational 6-year education model that provides a free community college and a path to a career for marginalized students. My co-author, Stan Litow, helped invent it, and principal Rashid Ferrod Davis has helped perfect it for the past decade. It’s told with the help of some inspiring students and educators. This was a joy to work on, as it is such an effective solution, a win-win-win-win in addressing inequity in education, dismal college completion rates, the lack of diversity in tech, and the need for rigor and high expectations

— Pamela Erens’s first book for children just published: Matasha, which takes place against the backdrop of the end of the war in Vietnam, is about the bridge from childhood to adolescence, family breakup, intellectual curiosity, and figuring out who can help when no one around you seems able to.

It's 1970s Chicago. Eleven-year-old Matasha Wax is in the sixth grade and starting to experience the trials of growing up. Her parents are in a standoff over her mother's desire to adopt a refugee child from Vietnam, and her best friend, Jean, is ignoring her. As she watches the other girls in school starting to grow inches and breasts, Matasha remains a puny four-foot-four—which means she will need growth hormone shots, and she is terrified of needles. Apart from her daily reading of the advice columns in the newspaper and keeping up with the Patty Hearst and Watergate scandals, Matasha is fixated by the story of a nine-year-old boy who has gone missing. When a mysterious letter arrives from Switzerland and her mother suddenly disappears, Matasha knows something else is terribly wrong—but no one will tell her what is happening, so she has to figure it all out for herself.

It’s aimed at older tweens and younger teens. Matasha received a starred pre-publication review from Kirkus, which said, among other nice things: "The many pleasures of this novel include its empathy and poker-faced wit, and the charms of its main character."—MEG WOLITZER, New York Times Book Review "Beautifully renders the slow-motion alchemy of growing up; mesmerizing and memorable.” For more advance praise & info on the novel, see the Matasha page on Erens's web page at www.pamelaerens.com

BOOK REVIEWS & COMMENTARY

(Alphabetical by Author):

If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW.

How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez

Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

The Black Ice and The Concrete Blonde by Michael Connelly

Assassin's Quest by Robin Hobb

Shaman's Crossing by Robin Hobb

Death in a Strange Country by Donna Leon

The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin

Voice Lessons: Essays by Karen Salyer McElmurray

A Promised Land by Barack Obama

Pale Horse, Pale Rider by Katherine Anne Porter

Sabbath's Theater by Philip Roth

Divergent, Insurgent, and Allegiant by Veronica Roth

The New Plantation: Lessons from Rikers Island by Jason Trask

Fools Crow by James Welch

Some of you know that for many years I've been involved in a small cooperative press called Hamilton Stone Editions. It has an online literary journal, The Hamilton Stone Review. full of terrific poetry and prose, as well as an imprint called Irene Weinberger Books. HSE and IWB have a sterling line-up of new books for Fall 2021. Take a look at the websites for these books and older, but still in-print, publications: Hamilton Stone Editions and Irene Weinberger Books.

Support independent voices!

CHECK IT OUT: There is an excellent new source of out-of-copyright free e-books. Standard Ebooks takes Project Gutenberg Books and proofreads and reformats. Yay E-Standard! Yay Project Gutenberg. (One caveat: if you are a Kindle user, you won't be able to email these books directly to your account. You have to download the e-book to your computer and transfer it to the Kindle via a USB cable).

Also, don't miss a terrific short short story by Carole Rosenthal in the excellent Spring/Summer 2021 issue of the Maryland Literary Review. For Rosenthal's context on the story, click here.

A variety of reviews this issue, including books by Philip Roth (again!) and Katherine Anne Porter, a YA post-apocalyptic trilogy, a book about teaching high school in the Rikers Island jail in New York--and lots more!

Voice Lessons: Essays by Karen Salyer McElmurray

McElmurray is well-known in Appalachian and Southern literary and academic circles. She has won multiple prizes and honors for her work, both regional and national, and has published with, among others, the University of Kentucky Press, the

University of Georgia Press, Sarabande, and Iris. This collection of memoir essays is my first encounter with McElmurray's work, and I should have known it much sooner.

The essays engage in a conversation about the culture of the Appalachian mountains. She speaks as one who has explored Europe and Asia as well as many cities and more that 35 different homes, as well as tracing her own family and her personal struggles. She has a dialogue with literature and with the people who teach literature and how to write it. She writes about how her discovery of expressive language changed her life, but she is critical of the kind of academic discussion that wants to put a distance on real life emotions. She writes about how a particular poetry class down played, even disdained, confessional poetry.

McElmurray's take on literature is about wholeness--a balance among form and structure and the digging out of our own personal--yes, emotional-- truths. She understands that in the end, you need all the parts.

A lot of this comes together in the the family stories, in particular her relationship with her damaged mother who obsessively cleaned house as well as cleaning her daughter--bathing McElmurray up into her teen years. Her father was a committed, rigid Christian, and there are a host of interesting aunts, uncles, and grandparents. The people and her powerfully sharp details of places and jobs and illnesses give the collection its depth. There are heart-wrenching scenes of the mother in the late stages of Alzheimer's disease, and there is a dream-fever exploration of the author's own experience of cancer treatments.

On the surface there is certainly a great deal here that could be called confessional–the mixed feelings about her mother, the details of colostomy bags, the struggle to study and write while you are working full time transplanting seedlings in a nursery. But the essays also experiment with form. One of the most interesting experiments is how McElmurray uses repetition. Incidents are told more than once, often in the same words, in different essays. Sometimes the passages come back word for word, and sometimes they reappear with the final sentence changed. Different nuances and depth come with the changed context. Towards the end, the prose works more than a little like a pantoum or villanelle. The essays were published in various periodicals before being collected in this book, but McElmurray is doing far more than recycling here: she is permitting us to remember, re-remember, re-experience with her some of what she has lived. We get the benefit of her memories and insights, and how she has used her life's materials to build her walls-- and her bridges.

Sabbath's Theater by Philip Roth

Every time I mention a Philip Roth book, some friend or colleague tells me another one I ought to read. The fascinating thing is that people have extremely different favorites. My friend hesitated a little as she recommended Sabbath's Theater, maybe because it is so--oh, let's just say it--dirty. Roth has never had trouble with pushing things to extremes, and this is where he creates a character who just lays it out there: he follows his politically incorrect penis through a life of enthusiastic sex acts over a base of emotional loss. He likes penetrating all orifices, and golden showers, and participating in woman-on-woman sex, but doesn't seem interested in sex with men. Otherwise, very eclectic.

The book is also plenty funny and has some really stellar sections. William H. Pritchard in the New York Times review when the book first came out in 1995 mentioned as one of the best sections my favorite too, the 50 or 60 page passage when Mickey Sabbath goes home to the Jersey Shore where he grew up in the company of his beloved older brother who dies in World War II. This brother is pretty clearly the real love of his life. This part, near the end, is soon followed by

Sabbath's memory of his long time girl friend/erotic partner as she is dying of ovarian cancer in the hospital.

He probably should have stopped there, but Roth was determined to have no sentimentality (even though it is what fuels Mickey Sabbath's life) and to end with more petty crime, hi-jinks, and slapstick. Roth is as always endlessly brilliant and burgeoning with language. Mickey Sabbath (what a wonderful name!) is a top notch character too, and when Roth is good there is absolutely no one better– but Roth is always subject to the dangers of his refusal to consider that some of his writing is not as good as other parts. There is bloat, and, for this reader, irritation.

The girlfriend Drenka is a good character, too, and for once one feels Roth actually has affection for a woman character, but of course her charm has to do with her sexual enthusiasm and her cute destruction of English idioms. She is good natured and sly but not educated.

The shape of the story is pretty much just Sabbath pushing as far as he can go. He is suffering, in physical and mental pain, obsessing over the loss of his sex life, obsession over death, especially his own, and how he wants to make that happen on his own terms. But we know from the beginning that Mickey Sabbath, while concrete and rich, is also a symbol, a Life Force, and that he will always choose life. Themes and plots aren't really Roth's strong suit. Tsunamis of language are. And a weak passage by Roth is better than ninety-five per cent of other writers' best ones.

Image above right is by Otto Dix ("Sailor and Girl") and was used on the cover of Sabbath's Theater.

A Promised Land by Barack Obama

I just finished the 700 page A Promised Land by Barack Obama. The giant nose-breaker of a book (if you try to read it in bed) was a birthday gift from my husband. I probably would never have bought it for myself, but I'm so glad I read it. It was, in some sense, a book I've been waiting for, a look at the political landscape from the top by a president with an active inner life, which I doubt many of them have.

Obama really is a fine writer–not a writer who necessarily goes deep in the way a great novelist does, and he is always performative--aware of his legacy and future historians as well as the general public and the myriad of individuals he met as president. His acknowledgments pages suggest a big staff of researchers and checkers—help on the details and probably a lot of respectful editing. He thanks some people for helping with organizing, but I would bet that the general structure–things like ending this first volume with the assassination of Obama bin Laden–was his own organizing.

As I said, he's good at this.

He also has an unspectacular but powerful ability to narrate a story, and he is able to summarize brilliantly bits of background and parts of history we've all forgotten or never knew. He's good on thumbnail sketches of character and even appearance. His seemingly fair but damning sketch of France's Sarkozy is a good example of this–as are all of his sketches of international leaders, actually.

The most out-and-out fun parts are obvious: the early campaigns, the good luck and successes. The parts about the family learning how to live in the White House. He seems generally honest, if careful about people whose careers are important at this moment– the prime example being Joe Biden, of course. He also has a neat trick of including near-foreshadowings of the coming of Trump, and choosing incidents and themes that contrast his administration, and Biden's, with that of Trump and the Republicans.

He doesn't go as far into his own motivations as some future biographer will do, but why should he? It's a presidential memoir, not a bildungsroman or a confession à la St. Augustine or J-J Rousseau. He is good on how he learns to make decisions in his progressive but practical way, and very good on what it's like to have so many explosive balls in the air at once in international affairs, natural disasters, internal politics, the search for bin Laden.

I do find Obama's conviction that he was the One a little arrogant and probably naive. Still, he learned fast–largely by knowing how to surround himself with good people, by team building. Complaints? Not really. The book is a fine example of its genre. There are people he is extremely careful of, notably Michelle, and of course the sexual passion between them that you could glimpse in photos and videos isn't touched on. He does come to bed late a lot and finds her asleep. The girls are pretty idealized, the way a fond dad who only sees them occasionally sees them. Weren't they ever obnoxious? My granddaughter is, and my granddaughter is just about perfect!

Biden may offer superior governance in the end, if he has extremely good luck and good health, and because he could hit the ground running so soon after being with Obama for eight years. But Biden has never inspired people the way Obama did. I'm thinking of a random young man on the New Jersey transit train siting across from me who proudly opened his shirt and pulled up a section of his boxer shorts to show the Obama print fabric.

For more, see the review in The New York Times by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie , who says, "Barack Obama defies the stereotype of the American Liberal for whom American failure on the world stage is not the starter course but the main. He is a true disciple of American exceptionalism. That America is not merely feared but also respected is, he argues, proof that it has done something right even in its imperfectness."

The reviewer in The Guardian says that "As a work of political literature A Promised Land is impressive. Obama is a gifted writer."

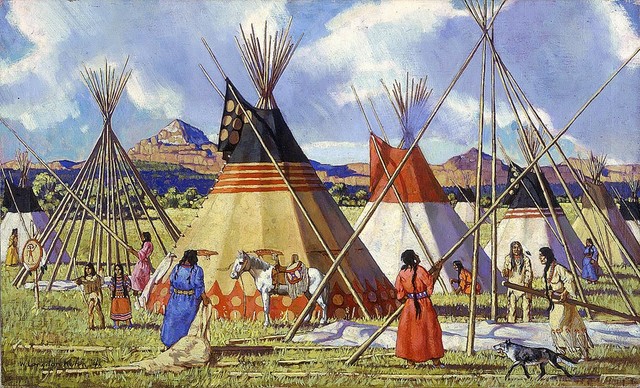

Fools Crow by James Welch

A real, enjoyable, emotionally satisfying American novel about native Americans. It uses an omniscient viewpoint with lots of characters and smoothly gives us entry into its world. Welch, who was part Blackfoot and part Gros Ventre, died of lung cancer in his early sixties, in the early 2000's. Fools Crow was written for literary people, but it has lots of action and even sex for the general reader, who now mostly watches Netflix et alia. Too bad, because this is a moving and entertaining dive into Plains Indian culture in the 1870's, that unpleasant part of American post-civil war history with renegade Confederate soldiers heading west (originals of the Cowboy books and movies of twentieth century) and the U.S. Government breaking one treaty with the Native Americans after the other, all while in the the white supremacists were "redeeming" the South. Massacres in the plains and northwest, lynching and Jim Crow laws in the old South.

The culture of the Plains Indians, often sentimentalized by those of European descent, was, of course, only a hundred and fifty years or so old--after first the Comanches and then the northern tribes got horses. The nomad life of following the "blackhorns" on foot and living off their meat and skins and horns was older. But that culture was changed by the coming of the horses, and then largely broken by the encroachment of the white people. This last moment of the plains culture is beautifully and even-handedly presented by Welch in this novel: the bloody inter-tribal raids and wars, the spiritual journeys and magnificent art work, mostly by the women.

The main character is a young man, first called White Man's Dog and then Fools Crow (Fools is a verb here) after his first raid on a Crow village. He starts out a little bit of a sad sack, gains confidence and skills as the novel progresses. Fools Crow's maturing and development are the heart of the narrative. He explores many parts of life: war, medicine, leadership, dreams and a lengthy spirit journey near the end in which he has a vision of the likely future of his people.

There is a lot here: some young Indian nihilist-gangsters, the "white scab" disease that the whites brought–the great sense of foreboding because of what we know is going to happen to soon to this culture we are glimpsing. Great deep losses, but somehow Welch, perhaps because he himself is the descendent of people like his characters, sees also the wiry spirit of survival through changes that no one wanted but many faced as best they humanly could.

With a handful of exceptions, white folks come off badly. No wonder the radical right wing resents full exploration of American history.

How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez

This is something I'd planned to read for a long time, and I guess I'd been planning it for much longer than I had thought, as it was published in 1991. Alvarez's is considered one of the first modern American immigrant stories. The book, quite short, is made up of stories about four sisters, although there is more about Yoyo/Yolanda, who appears to be most like Alvarez herself, than the others. The sisters were born in the Dominican Republic, but moved to the U.S. when they were young. The family was wealthy with a huge compound back in Dominican Republic, but long before the move, the girls' parents spent a lot of time in the US. Their Mami speaks English quite fluently, although she gets teased for her mutilated catch phrases, which are funny but a few too many. The girls' father is a physician and opponent of the dictator, which is what leads the family to flee to the States. That special background-- wealth and political involvement, plus the inevitable cultural conflicts, plus Yoyo's discovery and devotion to the English language-- gives the book its poignancy and charm.

Agnes Grey by Anne Brontë

Anne Brontë's first book--and the very first of the "Bell" family novels, even though she was the youngest of the four siblings. It's not Gothic at all (compared to Emily's and Charlotte's). It is about the horrors of being a governess, told in the voice of a young woman whose upper class mother gave it all up for a cleric, the narrator's father, who lost their bit of money in another of those ill fated speculations with a sailing vessel that sinks. He goes into a decline; Agnes talks her family into letting her become a governess.

What I like best is the realism of the work: the kids are holy terrors and Agnes is a prim little person, too rigid and proud to make a success, even if it were possible. She moves on to a different family with older daughters and gets an inside look at the materialism that her mother rejected for love. Like her mother, Agnes falls in love with a clergyman. He keeps his distance till he has a "living," that is, can afford a wife and family. I'm also very fond of how Agnes's mom, after her father dies, starts a school that looks like it is going to be a success. Her daughters are happily married to clergymen and she, energetic and clear-headed, runs her little business and is a mentor to many girls.

There is plenty of good nineteenth century appreciation of landscape, and lots of roller-coaster feelings, but Anne stays within the realm of what could really happen, and probably did. There is no madwoman in the attic, no demonish tooth-grinding Heathcliff. Anne may not have been a genius, but she's a solid, straightforward writer with a clear view of class consciousness, and an awareness of how little

boys were trained through cruelty to animals into oppressive beasts. There's a feminism of justice and a lot of anger in the book, which I look forward to reading again.

The Guardian has an interesting take on how Jane Eyre became the governess novel even though Agnes Grey was far more realistic and written first.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Anne Brontë

Anne Brontë's other book (she died in her late twenties) made me impatient with some tedious passages, mostly about Christian preaching. The narrator is a man this time, Gilbert Markham, who works pretty well as a man. Not terrible, but not as strong as the lengthy journal and letter passages he provides in the voice of his beloved, the tenant of Wildfell Hall.

This novel is far more overtly feminist than Anne's sisters' work. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the main character, Helen, is willful and verbose about her philosophy. She is certain of her righteousness and acts out what she perceives as her righteous duty. The descriptions of her husband's descent into brutal alcoholism are fairly shocking even now, but she is a tough nut.

Markham, the general narrator, is the one who has to come to her from his relatively low social position (he's a gentleman farmer who actually works with his employees and tenants). While he can take action in a way Helen can't, he ends up being the one who waits for her, and she is the one who bestows wealth and position on him.

Image above right: Anne, Emily, Charlotte Brontë.

The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin

Madeline Martin is a popular historical romance writer. Images of her books on the Internet show women in gem-toned dresses in company of bare-chested hunks--all in "highlander" settings. They are supposedly novels of strong women and the men who are strong enough to love them. The Last Bookshop is something much better, though. It is a historical novel of World War II about a fearful, shy, non-bookish young woman who comes to London with her best friend just before the Blitz and learns to love reading and gets a gorgeous RAF officer. She reorganizes and makes a success of a quaint bookstore while simultaneously mastering her fears and her low self-esteem as an air raid officer.

The start seemed a little clunky to me, as if the writer were having trouble integrating all the WWII slang and what the lives of two country friends in London might be like. They are very bright and chipper, and there are occasional moments when we approach the sentimental, but Martin draws back safely and gathers momentum, especially once the bombs start falling,

The final three-quarters, the Blitz part, are extremely well told, exciting and touching. Seeing Grace discover books is quite inspiring, as is how she reads aloud "classics" (nineteenth century British novels, mostly) to keep up the spirits of people in the underground bomb shelters and later in the bookshop. There's a lot of wish-fulfillment in the generally happy ending, but the book feels true to itself.

The New Plantation: Lessons from Rikers Island by Jason Trask

The New Plantation is a memoir of a white man who gets a job teaching in a public school for incarcerated teenage boys on New York City's Rikers Island. It is the nineteen nineties, and the narrator's eagerness to take on this challenging work is a combination of wanting to help young people, of not being certain whether he will be rehired as an adjunct college instructor, and of wanting to take on a challenge. He pits himself and his teaching strategies against the harshness of the situation of boys incarcerated for a variety of felonies, including murder.

The title refers to the U.S. prison system, but the book is at least as much in the tradition of teachers learning to teach, everything from 36 Children and Up the Down Staircase to Death at an Early Age and Teaching as a Subversive Activity--the nineteen sixties was a high point for these explorations, and the genre continues. The New Plantation deserves a prominent place on this book shelf.

Trask does a lot of soul searching about his own motivations, and admits to romanticizing the toughness and fierceness of his

students. He questions himself, and simultaneously works hard to create lessons that might capture the attention of these kids. He attempts to reach out to them using their own slang and dialect, and finds this is a sure fire way to amuse everyone. He tells them about himself, including who's in his family and what street he lives on. At least one student quietly threatens to track him down there.

One of the most chilling scenes is when he is reading poetry to a small group, seated together on a table. Two of the boys, with everyone else in on the prank, pretend to slash him with a razor. It's a moment in which Trask comes across as somewhere between courageous and wildly reckless. It is also funny. He observes the set-up and is almost certain that these particular boys wouldn't cut him, but he's only, say, 95% certain. The way it works is that they run a piece of plastic along his cheek: no blood, no real danger. He gets a little extra respect from them, but the scene, for me anyhow, really laid it out: the life those children have been pushed into and the pressure on men of all ages, including the teacher, to perform some role of a real man.

Trask in the end does better as a teacher than his employers expect and possibly better than he expects: he gets a few kids to dip inside themselves to write about their lives; he helps a few pass the G.E. D. test and actually graduate high school. The majority of his students aren't in his classes long enough for real relationships or learning. A few sleep through class. The Corrections Officers (a.k.a. guards) are really in charge, and they cancel classes for various infractions and the teachers sit n their rooms without students. Trask makes connections with several students, genuinely likes many, and shares with us his strong admiration of how all of them have played the hands they've been dealt.

The book is indeed another strong piece of evidence of how badly the U.S. handles its incarcerations, and also how so many boys of color are wasted by our social arrangements. Carolyn Chute, in her blurb for the book, calls Trask "a fellow traveler on the tangled up-and-down-and-around road that is the predicament of American life."

Perhaps my favorite part of Trask's book is his testimony to the many different individual teachers who managed to teach in these special circumstances--a public high school in a jail. He tells how teachers reached the children by being kind, by being fierce, by coming from pasts like their students, by coming from far away but caring.

His story is sharp and clear and far funnier than you'd ever expect.

Pale Horse, Pale Rider by Katherine Anne Porter

Katherine Anne Porter's most famous book, Pale Horse, Pale Rider, is actually three short novels, the title story plus "Old Mortality" and "Noon Wine. "Pale Horse, Pale Rider" uses her personal experience of having had the Spanish flu in 1918, and weaves a story about a young newspaper woman who gets sick, and her soldier boyfriend takes care of her--and gets sick himself

. Death, the pale one, is at the heart of the collection, and it is extremely interesting work. I read a 2009 New Yorker review of it by Hilton Als around the time the Library of America volume of her work came out. He talks about her life and a couple of biographies of her. I was especially interested in how she orchestrated her career, getting herself some of the earliest scholarships, fellowships, and writer-in-residence positions. She was a famous taker of lovers, and she probably drank too much, lived all over the world, but especially Mexico, always scrambling for the next gig. She was also beautiful, with black hair that turned white after she almost died of the flu.

I find myself fascinated by these stories, but at a distance. She writes with a kind of self-consciousness, a performing of the creating of literary art.

GENRE LINE-UP

I've been reading a lot of genre during the summer, perhaps filling the space that is usually filled by student writing. It's a treat to read not to improve someone's writing, or my own mind. I reread a couple of my favorites, but the first trilogy here is new to me--a highly successful YA series from @ 2010.

Divergent, Insurgent, and Allegiant by Veronica RothVeronica Roth wrote the first of these when she was still in college, and the series has been very popular, best selling, etc., and of course I hadn't heard of her. I was looking at a list of recommendations for post apocalyptic fiction because of something I'm writing. This is young adult and not bad at all. The first book of the trilogy is essentially a new-kid-at-school story with a feisty female narrator and a handsome smoldering mysterious first boyfriend. He has a touch of the Twilight vampire lover, but it's a very chaste love story. I'm not sure if this is a genre requirement or Roth's preference, but there is a lot of kissing and stroking cheeks and an occasional hand on the waist, but generally not much below the collar bone.

The action and violence are far more explicit than the sex.

Set in a post apocalyptic Chicago where people have divided into "factions" of various specialized interests and qualities, plus the "factionless" who are faction rejects/urban homeless. The divisions seemed to have worked fairly well up to the beginning of the story. Government, for example, was handed over to Abnegation, the ones who strive for selflessness and thinking of others first. Now things begin to fall apart. Tris, the protagonist, is born Abnegation, but

chooses to join Dauntless, a sort of Reckless Goth group whose signature move is to jump on and off moving trains.

The second book of the trilogy is Insurgent is a lot of fun too, except that Tris's problems often seem self-imposed and repetitive. Also, Tobias, her above-the-collarbone lover, is too good to be true. All the battles, quarrels, and revelations seem to be at about the level of intensity, right up till the final chapters when action and plot take over and it's all good.

Allegiant is the third and final novel. It gets fairly deep in its exploration of morality, which I like, but I do want to lay out my complaints. First, at least if you're an adult reader, you have to hold your nose over the apparently infinite number of times someone asks someone else "Are you all right? Are you all right?"

Next, this final volume has an annoying division of point of view, split between Tris and Tobias, both of them first person present tense. There is, it turns out, a plot/structural reason for the split point of view, though. Also, in this book, I think–but I'm not absolutely sure–that we get a sex act. Just one, a little ambiguous and definitely off-screen.

It occurred to me that Tobias wold have made a terrific woman lover–he has been in the first two books standard issue tough and mysterious, but the first person opens up his considerable vulnerabilities-- is this just old lady prejudice?-- but he doesn't seem to have enough testosterone in first person. So I was thinking it would make a great womanlove situation, but it's not my novel.

Roth does very well, however, with the outcomes of her story. I like a lot how she insists on people feeling the weight of their actions, including when they have killed in self defense or out of necessity for the greater good. One of the nastiest characters ends up asking for a mind-wipe to start over. There are also a lot of thoughtful moral considerations about group decision making and governance. In the end, even if the science is somewhat thin and vague, Roth plays out her story well, and even the double POV has a pay off in the end.

Death in a Strange Country by Donna Leon

This is a reread, and possibly one of the best of the Brunetti books. She tells her story better than in the first book, and is still excited and inventing. I had forgotten how cynical Leon is–there is no governmental justice for the murders in this one, rather the personal vengeance of a mother, plus one cleaned-up toxic waste site. The small changes are thanks to personal connections and working behind the scenes. She really believes in human depravity, which I am maybe too American-optimistic to accept. Leon was born an American too, but she has put on the garments and attitudes of a Venetian.

Meanwhile, there are the scenes of Venice, and the glasses of wine and coffee and little sandwiches and Brunetti's relationship to his father-in-law (I'd cast Charles Dance in the part, with Brunetti played by a not-too-young Marcello Mastrioanni). Also lots of interesting things about tourists and Italian dialects and mutual prejudices North/South Milanese/Venetian–and of course everyone versus the Americans in their little private-American military base.

Here is the 1993 original short review from Kirkus.

The Black Ice; The Concrete Blonde by Michael Connelly

These Harry Bosch novels do something dependable for me: all start well, take relationships seriously (including the detective's relationship to his monstrous serial killers). They are competently written, and have that wonderful underworld of Los Angeles that is especially enjoyable to me now that my son and my grand kids live there. I'm doing a second reading now, in order of publication, largely stimulated by the late great (but very different) t.v. series Bosch.

The Black Ice spends a lot of time in Mexicali and environs, chasing the history of a dead/suicide/murdered cop. There is a bull fight and a wealthy bull breeder, and there is El Temblor, the great bull. Bosch has sex twice, with TWO different women! and he has Eleanor Wing on his mind as well. Carefully written, fairly complex plot, still jiggling around Jerry and Irving Irwin (these guys are particularly good in the t.v. show, maybe better than in the book.) Anyhow, I enjoyed it.

The Concrete Blonde surprised me with who died and whodunnit--one important character dies who doesn't in the t.v. show version, so the death here was a complete surprise. Also, Bosch has a serious lover I totally forgot. The love affair seeped away long ago from my memory.) The later Bosch books give him his daughter as a way to connect to people without all the compromises he'd have had with a living partner/spouse. Also, Bosch is more emotional and less stoic in a lot of ways in this one.

The first half, with the split screen with him being on trial while he's on a new serial killer case worked nicely, and the research stuff on the porno industry was good.

Assassin's Quest by Robin Hobb