Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 211

October 24, 2020

This Newsletter Looks Best in its

Permanent Location Online!Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Octavia Butler, Livie Tidhar, Lillian Smith, Penelope Lively, Deboarah Clearman, Carter Seaton, Henry James

Meredith Sue Willis Has Two New Books for Fall 2020...

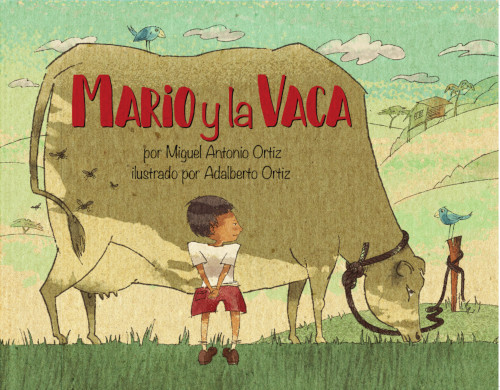

Latest Review of Soledad in the Desert!

Latest Review of Saving Tyler Hake

Free online writing exercise from Suzanne's McConnell's

new edition of Pity the Reader!.

.

In This Issue:

.

Special Halloween Review of "Turn of the Screw" by Eddy Pendarvis

Two "Chronicles" by Hilton Obenzinger

Good Reading Online and More

Readers Respond

Shorter Reviews

Irene Weinberger Books

Phyllis Wilson Moore's syllabus of

West Virginian/Appalachian Literature

BOOK REVIEWS:

Elizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938: A Salon Career by Mary Alice Heekin Burke

Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler

Remedios by Deborah Clearman

White Poison by Michael Harris Reviewed by Deborah Clearman

The Broken Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin

Judgment Day by Penelope Lively reviewed by Ingrid Blaufarb Hughes

Buried Seeds by Donna Meredith reviewed by Ed Davis

Debbie Doesn't Do it Anymore by Walter Mosley

The Long Fall by Walter Mosley

Known to Evil by Walter Mosley

The Other Morgans by Carter Taylor Seaton reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Killers of The Dream by Lillian Smith

Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith

Central Station by Lavie Tidhar

Saving Tyler Hake by Meredith Sue Willis Reviewed by Rebekah Ferrell

Book Reviews, if not otherwise credited, are by MSW.

.

.

This issue has a couple of firsts: a republished review of Donna Meredith's Buried Seeds, by Ed Davis, to accompany the one in Issue #208 by Eddy Pendarvis.

The second first is that I am, for the first time, running a review of one of my own books, Saving Tyler Hake, reviewed by Rebekah Ferrell. This novella, from the indomitable Mountain State Press--which features work related to my home state, West Virginia--is my first serious work centering on teachers. Teaching is my family business (father my high school science teacher, mother a substitute, uncle and aunts, and a grandfather who taught in a one room school with an eighth grade education!), but I haven't focused much on teachers in my novel writing. I've always imagined a big novel about teachers, but this novella is my first go at it.

We also have two more of Hilton Obenzinger's "Chronicles," soon to be featured in a hard copy book, and more reviews and commentary by Deborah Clearman, Ingrid Hughes, and Eddy Pendarvis,

.

.

Poetry by Hilton Obenzinger

.

September 9, 2020

.

.

Will anyone years from now understand

Or care about this moment September 2020?

How do we survive a sky that’s such DEEP TOTAL ORANGE?

ORANGE STREETS ORANGE HILLS ORANGE FEET

ORANGE LIPS ORANGE BAY ORANGE BRIDGES?

Can we put out all the fires?

Are we on the cusp of civil war?

Or has the civil war already begun?

How did we get lost in our own birth canal?

Where do we put our feet when there is no ground?

Who will breathe what we exhale?

What hopes have we squandered?

How many ventilators do we need if we never exhale?

Should I wait to write this poem until after the election?

Will I know who won by November?

When do these chronicles come to an end?

In November or January?

Or will they end in 2024?

Or when the fires are out?

When do we beat back the Boogaloo Boys?

How do we throw off THE GREAT ORANGE SKY?

ORANGE EYES ORANGE FEAR ORANGE DEATH?

Will this chronicle end after the plague has gone into hiding?

After I go into hiding?

We know the plague will never really go away

It goes into hiding like an angry rejected messiah

And it’s ready to pounce back at any time

A persistent hidden malignancy like Nazis

I stare at the all-encompassing Orange Sky and hope

We can put out all the fires

-- Hilton Obenzinger

.

.

.

.

.

RBG for a Blessing

RBG dies on Erev Rosh Hashanah

September 18, 2020

May her memory be for a blessing

RBG bless this day our daily hope

Let her memory be a shield

RBG protect us from harm

May her memory ignite

Young girls and boys to act

Let her story be an example

RBG live like her

May we make a planet worthy of her

May we remember all that she has done

And all that we should do

May her memory stop being undone

May her memory be a rocket ship for truth

May all the lies fall away

As she smiles at us from sky’s memory

May her memory give relief

May her memory give strength

May she soar as a diva

And we listen to her lucid aria

May her memory allow us

To outlive the virus

To put up with a lot of shit

Put up with smoke and flames

Put up with bizarre fake conspiracies

May her memory let us sing and dance

With patience, cunning, and courage

May her death be for a blessing on Rosh Hashanah

And every year may Creation

Weigh our souls

May RBG measure all our deeds

With equal justice

And may RBG

Bless us with her memory

.

-- Hilton Obenzinger

.

.

.

.

.

Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw: Where the Truth Lies by Eddy Pendarvis

Sometimes it seems every book written in the late 1800s or early 1900s is about an orphan. Remembering that an orphan is a child who has lost at least one parent, not necessarily both—names that first come to my mind are Huckleberry Finn, David Copperfield, Oliver Twist,

Little Nell, Lorna Doone, Jim Hawkins, and, for younger readers, Heidi and Pollyanna. If you include stories, especially fairy tales, the list gets much longer. I guess their popularity with readers (and writers) is partly because most of us harbor our child self deep in our memory, along with feelings about how frightened that child sometimes felt. In addition, most of us, maybe parents in particular, feel empathy for the hurts and hopes of children because children are so vulnerable without the protection of an adult. The orphans in those classics of a century or so ago survive the danger they confront, but fearing for them is part of the pleasure of the stories. In celebration of Halloween, I decided to re-read one of the most famous horror stories about a pair of orphans, a brother and sister—not Hansel and Gretel, but a story almost as famous.

The Turn of the Screw, Henry James’ novella, published in 1898, is set in England. The story begins on Christmas Eve, when a dinner guest offers a ghostly tale of something terrible that happened twenty years before when a young governess accepted a position to educate two orphaned children.

We learn that the children’s guardian, a bachelor uncle has placed his little niece, Flora, and nephew, Miles, in his country home, though he lives in London. He entrusts their upbringing to this new governess and admonishes her not to bother him with any problems. Not long after the governess arrives at Bly (maybe the name of the house should’ve turned her right around) she sees a ghost. At least that’s how it seemed to readers in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Now readers aren’t so sure.

For better or worse, Freud’s theories drastically changed how this story is read. Readers now are uncertain as to how trustworthy the governess’s perceptions are. That first ghost sighting, for example. She sees a man standing on a tower of the Bly estate and later describes him to the housekeeper as having red hair, short and curling; red whiskers; and a long, pale face with sharp, strange eyes. She notes that he is bare-headed. The housekeeper quickly recognizes this description as fitting Peter (yes) Quint, who had died not long before.

The governess soon sees a second apparition. This one, a woman, appears out of nowhere as the governess gazes across a lake. The woman, dressed in black, is described to the housekeeper as “pale and dreadful,” an image of “horror and evil.” Is she the former governess, Miss Jessel, who also died recently?

The governess is convinced the ghosts are after Flora and Miles to corrupt the children. Worse, she suspects that the children are complicit in this evil attempt. The housekeeper is skeptical, and so is the modern reader. After Freud, and in spite of his detractors, who would’t harbor suspicions of the significance of a bare-headed (a fact important enough for the governess to mention twice), red-haired man standing “erect” on (still another phallic symbol) a tower? And a female ghost seen across a lake—the watery symbol for female qualities, such as birth? These images appear sexually loaded to more readers today than in James’ time.

Even to readers of his day, James’ governess seemed anxious and overwrought. Early on, she seems unduly impressed with her young charges. On meeting little Flora, she says: “She was the most beautiful child I had ever seen.” We can accept that; but she goes on to call the child “radiant” and her beauty “angelic.” During the governess’ first night in the house, she thinks she hears a child, maybe Flora, crying “like one of Raphael’s holy infants.” According to the governess, Miles, who’s kicked out of school for behavior that, supposedly, is too bad for the school’s headmaster to specify—is also “incredibly beautiful.” The governess finds in his countenance “something divine that I have never before found in another child to the same degree.” These attributions of beauty and divinity contrast with her impressions of the ghosts, whom she regards as evil incarnate, particularly Peter Quint, with his “white face of damnation.”

So, does the governess actually see ghosts, or is the she mad? When readers ask that question, what they mean is how did the author intend for us to answer it. In spite of critics who say that the author’s intentions have little bearing on the literary work itself, some of us can’t help being curious as to whether James meant this to be a ghost story or the story of an obsessed woman whose delusions have a tragic effect on an innocent child.

My recent re-reading of the story suggested yet another possibility. Maybe Henry James intended to write a story illustrating that truth is sometimes unknowable—as insubstantial as a ghost.

James did’t intentionally make use of Freudian symbolism. He wrote this tale before Freud’s theories were widely known. However, that does’t preclude their being sexual symbols. All of us, even the greatest authors, communicate more than we intend to communicate. For one reason, few of our mental associations are available to our consciousness when we’re speaking or writing.

Whatever James consciously intended, his “potboiler,” as he called it, is a horror story that’s fun to read and puzzle over, especially so close to Halloween, when we symbolically greet Death by offering little hobgoblins treats to appease them and, maybe, keep grim truth at bay for another year.

Judgment Day by Penelope Lively reviewed by Ingrid Blaufarb Hughes

One of my favorite Penelope Lively novels is Judgment Day, a story which revolves around a church, in this case an ancient church in need of restoration. (At least bits of it are ancient, as one character puts it.) The village in which it stands is a “muddled place—its associations incoherent, its strata confused. Ugly for the most part, but shot here and there with grace….”

The church itself is “perilously sited beside the Amuck garage, its gray stone extinguished by lime green and tangerine plastic bunting… On the other side, the George and Dragon’s car park presses up tight against the churchyard wall… what must once have seemed so large, so solid, so impregnable, now squats small and a little apologetic: a pleasing anachronism, of architectural interest. Time has juggled the order of things.”

The story is told mostly from the viewpoints of three characters. Clare Paling is affluent, bookish, happy with her husband and two children. She lives across from St. Peter and St. Paul and agrees to help raise funds for repairs out of interest in its history and a need to be occupied. The vicar, George Rad well, who lives next door to her in a twin house, is a dull, uncertain man who stumbled into his work for lack of other interests. He is irritated by Clare’s matter-of-fact agnosticism, even as he develops an attraction to her, or perhaps because of it. “She made

him think of gooseberries. He had never known if he loved them or hated them; that acid compelling taste, they way they furred your mouth. He did’t know if he wanted to hit her or grab her.” [When Clare tells her husband that George Rad well seems to have “inappropriate feelings” for her, Hubby laughs, "at length.”]

Sydney Porter, another neighbor of the church, is a retired accountant and churchwarden, who has organized his life to protect himself from the kind of pain he experienced when his wife and daughter died in the Blitz. An occasional fourth point of view is that of a boy, Martin, whose family lives next door to Sydney Porter and who Sydney allows himself to adopt, despite his vow.

Besides these people, all living on the green by the church, there is the constant presence of the biker boys, a gang who roar around the green at night, overturning garbage bins, breaking a window here or there, requiring the vicar and Sydney Porter to lock the church at night. Claire considers “these nocturnal visitations… the unleashing of some elemental force, sinister and uncontrollable [by] restless, frustrated, destructive youths.”

Lively explores other forms of violence as well, both accidental and deliberate: Sidney Porter’s war experiences; Claire losing her temper over a parking space; one of the fighter jets that various characters have admired crashing into a crowd at a nearby airs how killing several people. St. Peter and St. Paul itself has a bloody history—the killing of several Levelers in the churchyard in the 17th century as well as the trial and transportation to Australia of farm laborers demanding better wages in the 19th century. These events become the subjects of a reenactment to be performed on the day of the great fund-raising event for the restoration.

So history becomes another of the subjects of Judgment Day. Clare Paling, who remarks often on its misery, violence and bleakness, is as often challenged by the irritable Miss Bellingham who feels sure that Clare’s views are too gloomy and disparaging of history and that the public would rather see charming children in pretty frocks doing traditional dances than a staging of the church’s violent past. One of the pleasures of the novel is Clare’s intelligence on this and other subjects. When Sidney Porter, watching a rehearsal of the reenactment observes, “You can’t help wondering if it’s anything like it was…” Clare responds “The past is always our own projection. I mean the real past is no longer accessible, because you can never divest it of our own wisdoms and misconceptions.”

She’s also amusing on the new Bible, when she feels she should expose her children to religion and in church reacts against it. She finds herself thinking: “I beg your pardon? You did say Corinthians one thirteen? Is nothing sacred? Where are the sounding brasses and tinkling cymbals, for God’s sake?.... Where are the paths of righteousness and the valley of the shadow of death… God never told people to reproduce, he told them to be fruitful and multiply…..”

Lively is always in command, moving easily from one character’s head to another’s or sliding into omniscient, describing Sidney’s pleasure when he finds himself taking care of a neighbor’s child, the vicar’s crush on Clare.As the story builds, the church assumes its lost glory under the spotlights set up for the pageant. Then the ugliness suggested in the first pages manifests, along with the satisfactions of alterations in the major characters.

If you read this book you may find yourself looking for more Penelope Lively novels. One of her many virtues as a writer is that she never repeats herself.

.

Remedios by Deborah Clearman

A few months ago I reviewed the first of Don Winslow's novels about the Mexican drug cartels, The Power of the Dog. I did not read the rest of the trilogy, and probably won't. It is well-researched and, I believe, fairly close to a true picture of

the mega-violent drug cartels, but one of these multiple-hundred pagers is enough for me. I'm willling to be choked by the horror once, but I don't need to repeat the experience.

Deborah Clearman's new novel Remedios, set in Guatemala, covers some of the same territory. The horrors are here, but she takes her time with the people. She writes about what organized crime does to people on the ground--mothers and honest police officers and college professors and a kid who wants to be a chemist and ends up making methamphetamine for his father's attractive friend who brings the drug business to the fictional town of Remedios..

Clearman gives acknowledgments to many people she knows in Guatemala who are not, she says, models for the people in her novel, but you trust her knowledge of how drug manufacturing and selling can corrupt and destroy the people it touches

She writes about one very close Guatemalan family that is far from poor, but still besieged by financial woes and by the memories of the political Violencia of the 1980's. The most prominent character, Fernando, is a college professor who is passionately in love with his wife and feels powerfully responsible for his extended family. He is genuinely and generously delighted when Memo a friend from high school– for whom Fernando as a teenager arranged a soccer scholarship–turns up again. Memo is strong, secretive and attractrive to everyone around him: especially to Fernando himself, to his wife, and to his son.

We get well-handled points of view for all those characters, and for Memo too, which is a bit of a coup for Clearman, because Memo holds himself away from all confidences and as much as possible from feelings. There are deaths, but there are also survivals.

It's an excellent story, but perhaps even more than the story, I like the layers of Guatemalan society: the way the families are organized, the occasional wry judgements on norteamericanos, the religious lines drawn between traditional Catholics and the evangelicals.

It's a moving, sad, and very worthwhile book.

.

.

.

.

Central Station by Lavie Tidhar

A lot of Tidhar's focus is on world creation, which always pleases me, as does the big cast of characters. This 2016 book won or was nominated for a ton of science fiction awards, and won the 2017 John W. Campbell Memorial Award. The novel is set in the future at an enormous travel hub (space travel) on the border between the Israeli cities of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. The community around it has a wonderful mix of ethnic groups whose families immigrated: people from or with roots in China and Nigeria along with Jews and Arabs and various others.

One interesting idea is that the world wide web has gone interior: every baby is at birth implanted with a node that allows the person it becomes to be part of the "conversation," which is everything going on everywhere (including across space) all the time. You can pull out information as needed, of course, or just

listen, or send out a feed of your daily life and musings. The plot, such as it is, has two people arriving at Central Station: one to see his father die (the death takes place at the very cool Suicide Park), and, not by plan exactly to resume his great love affair. The other arrival is a strogoi, a young woman who is a kind of vampire: she has overdeveloped canines, but doesn't suck blood. Rather, she takes data from her victims, who seem to like it. There's a "crippled" book seller who has no node and lives in silence--that is, doesn't take part in the conversation. He and the strogoi have an affair.

There is also a woman who makes a living in the gaming universe. Her love affair is with an ancient soldier, a robot with a little bit of dead human soldier still animating him. There are some very strange children, from the vats (an alternative to biological gestations and birth) who may or may not be about to be the next stage of "human" evolution. (Tidhar apparently uses the Central Station universe as a setting for the majority of his straight SF stories).

The thing I like best about this is that everyone keeps keeping on, which is really what human beings do, until we die. We now are in the middle of a terrible pandemic with dire political circumstances, but hour by hour, we eat, chat, read, do chores, have sex, try to figure out how to get the best for our children, etc.

So unlike too many science fiction and fantasy novels, this one is a slice of future life with plenty of danger and mysteries. Some but hardly all are thwarted or solved–and then we go on. It's a kind of high realism, if you like.

He says in an interview at Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, "I like that SF allows you to talk about the big questions—what is life? Why are we here? Is there a God?—whereas in the rest of fiction, a lot of the time we pretend that Earth and humans are all there is, and this huge, strange, mysterious universe isn't out there. But it is out there! It's right there! How can you not write about it?"

Parable of the Talents by Octavia ButlerButler is prodigious. I liked the Parable of the Sower, the first half of this series, and had trouble getting into this one, but once I was in, I was all the way in. It is made up of a mélange of journal entries and selections from Lauren/Shaper/Sharer/Olamina's poems that make up her religious text, the Book of Earthseed.

It's a post-apocalyptic world, one that actually functions in some ways. Late in the book a new political administration comes in and offers some hope after the awful events under the religious right-wing president who was elected at the beginning of the book.

Butler builds up a consciously created community and then tears it down brutally: she doesn't seem to mind doing this. There are a lot of damaged and re-damaged people, but the heart of the story, or maybe one way to read the story is that a woman invents a religion (Earthseed) which has as its essential dogma: God is Change and Change is God. The religion insists that we shape Change/God even as Change/God shapes us. It's simple and practical, with only one weirdness, which is that there is a Destiny for human beings to go to the stars and seed the planets there with earth people and plants and animals.

The novel lays out this belief system not as something necessarily true but as a stark contrast to the Christian American Church, which includes, along with a lot of your normal uptight judgmental Christians. a host of evil "Crusaders."

I really liked the idea of a sincere, struggling woman who has invented a religion and is a natural leader of people. The heart of the novel is her struggles, her loves, her quest. Her baby is stolen from her early on, and there is a question about how hard she is trying to find her (she thinks she is). The baby becomes the daughter who is the impresario of the novel, telling a little of her own story but mostly sharing and commenting on Lauren/Shaper/Olamina's journals. Eventually they meet, and it is interesting, if not easy or even good, but it is very powerful.

Butler is the real thing: inventive and humanistic, and died way too soon.

.

.

.

White Poison by Michael Harris Reviewed by Deborah Clearman

In this sweeping epic we see the California Gold Rush and war of extermination against the native peoples of northern California through the eyes of protagonist Alexander Wells. At age 76, Wells has just received a medical death sentence and decides to write down the story of his life, beginning in 1852 when as a 17-year-old farm boy from Illinois his wagon train is attacked by Medoc Indians. Full of rage and blood lust, young Alex joins a posse of Indian fighters to punish the Medoc. The ensuing massacre instills in Wells a burden of horror and guilt that haunts him for the rest of his life.

Harris convincingly portrays Alexander Wells through stints as a successful prospector, failed rancher, failed husband, heartbroken father, and successful lawyer as he grows from rough youth to seasoned elder. Through tragedy and hardship, his moral fiber is constantly tested. The book is a tour de force in capturing a life.

Moreover, this life personifies sixty years of brutal history in northern California. Rigorously researched, Harris incorporates a number of historical figures into the novel and places his protagonist into actual events. He even quotes extensively from Joaquin Miller, the flamboyant “poet of the Sierra,” who lived with and wrote about the California Indians.

The catalyst for the fictional memoir is also a historical event: the dramatic discovery in 1911 of Ishi, the last wild Indian of California, sole survivor of his Yahi people. Alexander Wells dreams of meeting Ishi to solve a mystery: was the entire Shasta tribe murdered by deliberate strychnine poisoning at a treaty-signing feast in 1851?

Whether or not the Shasta were fed beef tainted by white powder, their people were all but wiped out by the end of the century. By weaving together history and fiction, Harris has created a powerful and poignant masterpiece in White Poison.

The Other Morgans by Carter Taylor Seaton reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

The prologue to Seaton's new novel feels almost epic in the way it places the main character, her problem, and her opportunity right in front of us at the outset. We first see her alone on the family farm in Fayette County, West Virginia.

At the edge of the pasture stood a young woman in jeans so tight her mother often questioned how she got them on. A single black braid split her back like an exclamation mark. In her left hand, she held an envelope from the Fayette County sheriff's office. Her heart sank as she stared at it. She knew what was inside—the farm's annual tax bill.

In her right hand is the other piece of mail addressed to Audrey Jane Porter. She turns the cream-colored envelope over to open it and sees an embossed gold crest and a red wax seal. The contents of this envelope change her life.

The letter inside brings word of an almost impossibly huge inheritance. As the only living descendant of Jackson Morgan, a man she's never heard of, AJ is heir to the man's millions. Soon, AJ learns that, in order to gain her inheritance, she has to agree to live at Morgan's home, Langford Hall, in Dillard County, Virginia, for a year and learn how to manage his four thousand acre farm.

Silver linings come with clouds, and the changes in AJ's life aren't all for the good. Leaving West Virginia for an extended period of time poses problems for her. AJ and her daughter, eight-year-old Annie, live with AJ's mother, Alice, on a family farm. With a lot of hard work, AJ and Alice eke a living out of their small farm. Alice is too old to work the farm without help, and Annie doesn't want her mother to leave. The problems leaving pose, however, are minor compared to some that AJ encounters during her sojourn in Virginia.

When she arrives at Langford Hall, a congenial older woman named Isabelle is comfortably ensconced in the house during work days and, understandably, hopes to continue working there. Isabelle, who was, among other things, an assistant to the deceased millionaire, has a sentimental attachment to the place and a thorough knowledge of its history, which she shares with AJ through conversation, old journals and letters, and a visit to the family cemetery where the Virginia branch of the Morgan family lies buried.

Author Seaton's eventful story of the happenings during AJ's stay raises many important social issues, especially issues related to gender. Of particular interest to me was the fact that a good percentage of the male characters, alive or dead, are (or were) terribly flawed in their moral make up. Their destructive responses to life's challenges ranged from slave-holding, to drunkenness, to wife-beating, to larceny. Heroes like Ben, a World War II pilot, and Moses, more loyal than his slavemasters had any reason to expect, are few and far between. The women's flaws are minor by comparison—AJ's mother is timid at times and often narrow-minded; women in AJ's hometown are gossips; and AJ, though strong, is full of self-doubt.

In a way, this novel is the reverse side of the coin to one of my favorite books by Seaton: Father's Troubles. Set in the early twentieth century, it too focuses on a family history. Father's Troubles depicts the misfortune that acquiring a fortune brings to a Huntington, West Virginia, man and his family. In that story, the influence of one man's actions on those who love him portrays even greater emotional stakes than are at issue in The Other Morgans. This new novel makes a fine companion piece to the earlier one. .

Whether flawed or heroic, male characters get the lion's share of drama in AJ's story. So much so that for a time I rooted for Isabelle to be secretly plotting to take over the estate, but Isabelle's not the antagonist. In fact, as with many excellent novels, the protagonist of this tale is also the antagonist. In this sense, The Other Morgans is the story of an intriguing psychological struggle. To fulfill her dreams and her duties to herself, her family, and her community, AJ first has to be clear about what her dreams and duties are. The story's end offers a poignant contrast to its beginning.

Buried Seeds by Donna Meredith reviewed by Ed Davis

(See another take on Buried Seeds from Edwina Pendarvis in Issue #208)

I found myself excited to learn that Donna Meredith’s new novel Buried Seeds (Wild Women Writers, 2020)was about, among many other things, the West Virginia teachers’ strike of 2018. I’d closely followed the event through the media and the involvement of my teacher-niece, but I longed to experience what the strike felt like—and knew from having read her novel Fraccidental Death that Meredith would not disappoint. Buried Seeds is actually two novels beneath one cover, alternating between Clarksburg, WV teacher Angie Fisher’s strike narrative and Angie’s great-great-grandmother Rosella Krause’s early twentieth century activism in the struggle for women’s right to vote. If you liked Barbara Kingsolver’s parallel plotlines in her latest novel Unsheltered, you’ll doubtless

enjoy Meredith’s interesting mashup.

Angie Fisher is an excellent Everyteacher, fiftyish, funny and self-deprecating—but what makes her so relatable, besides her compelling voice, is her super-pressurized life. When Angie reluctantly accepts leadership of the American Federation of Teachers in her district, she sets herself up for an agonizing dilemma: how can she lead a strike when her unemployed husband Dewey is applying for work with the local FBI, likely to frown on such law-breaking? During this time, she also deals with her dad’s growing dementia, her sister’s divorce and her daughter, a single mom, giving birth to a child with severe hearing loss. Money is a big problem, and we see all too clearly why state teachers are disgusted with a legislature that wants to give them a mere 2% pay raise while health insurance premiums skyrocket.

After Angie and Dewey are forced to move in with her parents, Trish and the new baby Bella soon follow—and if the old farmhouse weren’t already over-crowded, sister MacKenzie winds up there, too, when she leaves her husband. While such pressure may to some appear over the top, my own first-hand knowledge of close families tells me otherwise. These developments remind me how I felt reading, in Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, a scene where the cash-strapped protagonist is Christmas shopping. I’m grateful to Meredith and Kingsolver for making me relive the ache of poverty I felt in my own childhood, nowhere better represented than in the fact that hearing aids for Bella, not covered by the teachers’ current insurance, will be an impossible expense for this family.

Alongside Angie’s anguished life, Meredith shoots us into the early 1900s, where we meet, alongside Angie, her great-great grandmother Rosella, who’s endured similar suffering. Adopted young, Angie knows nothing about her parents, much less this long-lost relative. Rosella, an artist, is now in San Francisco, along with her fourteen-year-old daughter Solina, for the opening of Rosella’s pottery show. The account we’re reading is based on the scrapbook Angie’s mom gifted her with. Scenes are recreated through the diary Solina kept, describing her mother’s life story as she related it during this auspicious trip. Even more important than finding out that Rosella was a great artist is that she was an activist as well, working tirelessly for women to earn the right to vote in 1907. A former journalist, Meredith is a scrupulous researcher. I learned a lot about other significant women’s issues while also enjoying exciting plot twists and turns.

And there is plenty of plot in this book. A seasoned writer of mysteries, Meredith doesn’t ignore the need for suspense to keep readers tantalized. In Angie’s story, we learn quickly that Rosella was her great-great-grandmother, but who was Angie’s mother and father? And while many readers will know how the WV teacher’s strike turned out, we want to know if Angie and her husband will reconcile. Perhaps most heartbreaking: will infant Bella get her hearing aids? Similarly, the Rosella narrative is fueled by wondering who reported her as a “bigamist and baby killer” to the press and whether her greatest artistic achievement will be ruined by the media attack? All eventually comes clear, along with many other shocks and surprises.

Buried Seeds is rich indeed. If I have a quibble with it, it’s that perhaps it’s a little too rich as the author includes so much, especially in Rosella’s section. But if it’s a bit overstuffed with event, it does not ignore character, to me the gold standard. By novel’s end, I do know, through Angie Fisher, something of how it feels to lead a strike for justice as well as economic necessity. It feels like the only thing a person of integrity can do, in order to live with oneself and face one’s children and grand-children. I’m grateful for that vicarious experience.

.

.

.

Saving Tyler Hake reviewed by Rebekah Ferrell

As each set of wandering eyes and gossiping lips hovers over a tragedy in Smith County, West Virginia, a group of middle-aged women is sent back thirty years to when they sat at the very school desks they now teach in front of.

Through the narration of Tyler’s 10th grade English teacher, Robin Sue

Smith, author Meredith Sue Willis takes the reader on a journey through the inner workings of a close-knit town and the relationships within by applying themes of regret, old grudges and uncomfortable age gaps.

Willis, a West Virginian native now living in New Jersey tied her story to its setting all the way to the editing process – by asking that this novella be published by West Virginia’s oldest traditional literary press, Mountain State Press.

Through the storytelling, heavy Appalachian plot line and hints of the classic country twang inherited by each character, the reader can infer that though Willis’ body moved elsewhere, her heart and soul stayed in the great Mountain State.

Saving Tyler Hake was a compelling read from start to finish. With the heavy use of dialogue, the relationships within the book flourish, proving that any incident within a small town has a way of sneaking into every crevice of daily life.

With the use of flashbacks, Willis bridges time in a small town, as well as the relationships that grow and fade therein. And with an end tying up what had happened to Tyler Hake after all, we see that good can come of the misfortune from being born on the wrong side of the bridge.

Elizabeth Nourse, 1859-1938: A Salon Career by Mary Alice Heekin Burke (with Lois Marie Fink)

Nourse was an American expatriate in Paris, a contemporary of Mary Cassatt and Gertrude Stein. She was not, however, an experimenter, but a woman of deep religious feeling (Catholic) who loved nuns and mothers and children as subjects, and also European peasants, who were her most frequent subjects for paintings.

She lived with her sister in France.. They spoke only French to each other, and she showed in the big Salons. This book is the catalog of her 1980's retrospective in Cincinnati, where she was born. She had a twin sister who died as a young married woman.

Part of what's interesting about this is how she was a so-called Academic painter, but took whatever she wanted from the Impressionists and others. It is also instructive to learn how many women, including Americans, were studying in Paris in the 1880's and 90's (there was a wonderful exhibit at the Clark in Williamstown, Massachusetts in 2019 that was about that).

Nourse crossed paths with many important artists, but was pretty focused on making a living as an artist. She was extremely serious and talented, working hard, doing everything, but never interested in art for its own sake. She always painted subjects.

Oh, and all the people in her pictures are beautiful in her eyes and how she presents them. The old are beautiful through lines of experience, the young gaze out frankly at us,, and that is their beauty. A lot of her work is a little quiet for my taste, but attractive in this present time of enforced calm and great anxiety. And the story of what it took for an American woman to have this career is fascinating.

.

.

TWO BOOKS BY LILLIAN SMITH

Killers of The Dream by Lillian Smith

Killers of the Dream by Lillian Smith is an historically essential book--a direct look at the effects of racism on Southern white people. Smith says early on that this is not a personal story--and, in fact, she avoids using many stories. She insists she isn't doing doing memoir or fiction, and the result is passionate but abstract. The parts that are most vivid are, in fact, the stories, the concrete examples of events in her childhood and other dramatized examples,. She tries to write about everyman and everywoman, but it often seems over-generalized, and the style is impressionistic, with heightened language that is too imprecise and overwrought for my taste.

Whatever its flaws, however, it is one of the first of its kind: an exposure of the wages of racial sin, as well as sexism and religious bigotry, on the white people of the American South. It was published in 1949,

with revisions in the early 1960's, and a 1994 introduction.

The book has some wonderful moments, especially the story from Smith's early life of how her family took in what the town perceived as a white child mistakenly living with black people. The girl is simply snatched from her foster home, and brought to Smith's house, where she becomes Smith's companion, sharing clothes and play. Further investigation by the town elders indicates that, no, the child isn't white but black, albeit very light skinned. She's sent off to a "colored" orphanage, in probably the worst situation yet. The girl Lillian-- quite reasonably-- just doesn't get it. If the other girl looked white, why was she black? How could she be one thing and then another and then snatched back to the first thing?

The point is, of course, the arbitrariness of race, but here we're getting it from a white witness, who ultimately spent her life teaching white girls a better way and joining in as an ally the early struggles of the Civil Rights Movement.

Strange Fruit by Lillian Smith

Lillian Smith's best known book is a novel published in 1944, before Killers of the Dream.. This novel, like the nonfiction book, is mostly about what racism does to white people and to a Southern town, although she does write several educated characters of color. One is a doctor who is deeply kind and sacrifices his own anger to be able to heal his people. She also creates two more college educated black characters, a brother and sister, Bess and Ed, who are believable. I was less satisfied with Bess and Ed's younger sister Nonnie, who is part of the couple whose love story destroys a lot of people

Nonnie is, like the little girl in Lillian Smith's real life story, pretty much white in appearance, and she takes a white lover, a young man she grew up with, who is briefly inspired by his experience in war and his love to turn against the racist culture of his community, but he falls away from his best moment quickly.

There are maybe a dozen or more point of view characters, so it becomes a group novel, or perhaps a novel about a community in South Georgia, a town the produces turpentine and cotton. The novel has a murder of passion and ends with a lynching, although the title is not from the Abel Meerpol aka Lewis Allan song made famous by Billie Holiday. Smith says it was about what Southern segregation and Jim Crow did to twist its children and turn them into strange fruit.

The book was, to my surprise, a best seller. I was expecting a historical curiosity, but it is in fact quite gripping. Smith handles her multiple points of view skillfully, and, as I suggested her African-American characters aren't half badly done. The lynching is seen and smelled, but not narrated directly.

Banned in Boston and Detroit and by the US Post office, Strange Fruit sold millions anyhow, and probably ought to be on high school reading lists, but It won't be, of course--there's too much sex and too many N-bombs.

Apparently Smith didn't write anything this good again, although she wrote a lot, much of it nonfiction, some polemical. She ran a camp for girls and young women, was an activist and writer for the whole rest of her life. She never wrote directly, however, about her own sexuality and her long relationship with another woman..

For more on Strange Fruit and Lillian Smith, read some of these reviews and essays:

https://www.bookforum.com/print/1802/strange-fruit-by-lillian-smith-7794;

https://www.artsatl.org/review-uga-press-lillian-smith-reader-fortifies-authors-brazen-legacy/; and

https://www.thedailybeast.com/lillian-smiths-bombshell-novel-about-interracial-love .

.

.

.

.

SHORTER REVIEWS, MOSTLY GENRE

.

Three by Walter Mosley: The Long Fall , Known to Evil, and Debbie Doesn't Do It Anymore

I seem to be consuming Walter Mosey books like potato chips. These are the first two Leonid McGill mysteries plus a stand alone book in a first person woman's voice.

I like McGill, althoug not as much as Easy Rawlins. He's an ex-amateur boxer, mid-fifties. The place is New York City instead of Los Angeles, and the time around 2008 or 2009. I miss Los Angeles in the nineteen sixties, but New York is always fun. We're up to computers and cell phones, but not smart phones.

McGill is shortish and thick, only a h.s. education, and a background of running

errands and ruining people for the Mafia, but never killing anyone. He is of course well-read and extremely smart and good at lots of things, as a PI and Mosley protagonist should be.

His MIA father was an ideological communist, and McGill, of course, suffers a lot, both beatings and psychologically. His favorite child is not his genetic son, and he has a strange flat relationship with a wife who has been serially unfaithful (two of three kids not his). She's trying to get back in his good graces, but he isn't having any of it, although he supports her to keep his family together. He loves someone else, and once again, in both of these books all these backstory details are what I like best, and also the various low lifes and nasty rich white people who pop up. McGill is always thinking, always on the job, and always enjoying the pleasure of outwitting the people who underestimate him.

And finally, a standalone Mosley called Debbie Doesn't Do It Anymore, is not a murder mystery at all, but has violence and a lot of violence-prone people, including another of Mosley's signature cool professional killers who helps the protagonist. It is set in the so-called adult film industry, first person narration by Debbie Dare/Sandra Peel. She's quite appealing and also extremely explicit, as she warns us at the beginning. The final third comes up with a pretty hokey plan to commit suicide that I don't really find believable, but maybe it's the best Mosley could think up to raise the ante for the end. I was perfectly happy with her retirement from the adult film industry, her husband's death, a couple of attacks on her for money and passion. But in spite of my sense that I didn't believe the plot development, it works or tying up the threads. I liked the book a lot: as with so much of his work, it's short, crisp as a cracker, heart and politics in the right place. For a summary and some more comments, see the Chicago Tribune's review.

Big bonus: his world view never sets my teeth on edge.

The Broken Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin

This is the second of Jemisin's first trilogy, which precedes The Fifth Season et alia, and the others. This one takes place in the city of Shadow, beneath the World Tree. The narrator is Oree Shoth, a blind artist who enjoys her life selling tourist kitsch in a busy, friendly marketplace.

The human-turned-god and the Nightlord from the first book make a cameo appearance in this one, but there are plenty of other gods and godlings. The plot turns around the question of who is murdering the godlings?

So we have a mystery that carries us through the story with great panache. There are too many gods for me--this is where fantasy falls down in my estimation: it's hard to get too concerned when you don't really grasp or remember what each character has the power to do or not. Is the point they're just folks, like very rich very powerful folks? I'm not sure, but, hey, it's N.K. Jemisin and she's always worth reading.

.

.

.

READERS RESPOND

Darrell Laurant wrote: "I loved the essay on typos by Edwina Pendarvis that appeared on your book blog. I spent 30 years as a newspaper reporter and columnist, during which I probably committed enough typos to fill a volume in themselves. Some got caught, many didn't. Once, we ran the wrong date on the masthead at the top of the front page -- leaping from Wednesday to Friday and skipping over Thursday -- perhaps causing lots of readers to fear they had inexplicably lost a day out of their lives. I've always compared typos to cockroaches. You can spray and spray and feel confident that they are all eradicated, only to find a new crop the next day. I once decided to test our readers by printing a short piece of writing that contained a few intentional typos and challenging them to locate them. And they did, along with two more typos in the piece that were unintentional."

Darrell Laurant runs a great site for writers and readers at snowflakesarisewordpress.com

.

.

GOOD STUFF ONLINE & ELSEWHERE

Lewis Brett Smiler has a short story "Down the Stairs" in the Horror Anthology Night Terrors Volume 4. It's a Kindle book, available on Amazon.

.

.

.

Yet another of Hannah Brown's wonderful true stories about life with her son Oren. This one is "One Morning in Maine," and this time she and Oren go to Yom Kippur services without her having had her morning coffee. I've been linking to this series of essays for the last several issues. Just as a reminder: Hannah Brown is the author of If I Could Tell You, inspired by her experiences of raising a son with autism.

She has been the movie critic for The Jerusalem Post since 2001. She is a lifelong writer, going back to elementary school when I knew her at P.S. 75 in New York City.

Suzanne McConnell speaks about her book Pity the Poor Reader on Youtube.

Some old material on editing: These pieces are 5 years old, but of more than archival interest: Dan Menaker wrote on the ideal of editing and the publishing that (used to?) make it possible. I blogged a short response.

Check out:"Snowflakes in a Blizzard,"an author-centric free book marketing service created by author Darrell Laurant that is followed by hundreds of bloggers. Each week he features three books -- novels, non-fiction, poetry, short-story collections -- in individual posts. He says, "Some of the authors we embrace are obviously in need of more exposure. In other cases, the inclusion of a book is simply an effort to get unique writing out to our blog followers." Take a look at the website. It has a template for submitting your book to the project. And it's featuring one of my books!

Phyllis WIlson Moore's syllabus of West Virginian/Appalachian Literature

Phyllis Moore's syllabus for a course on West Virginia literature, "Rooted in Solid Ground: Journeys into Appalachian Literature." See syllabus here.

(From the introduction)

"Many of the seventeenth and eighteenth settlers of West Virginia came from Scotland, Ireland, England, Germany, among other European locales, to ports on the eastern coast of North America. They moved on to (what was then) the mountain wilderness west of the colonies.. These settlers and others brought their history and heritage, memories and stories, as well as the drive to be independent land owners. They were not here first or here alone, however. They massacred, uprooted, or in the best cases merged with Native Americans. Some brought with them, or later purchased, African Americans as slaves.

"The mountains’ mix grew to include increasing numbers of ethnic groups from countries such as Italy, France, Poland, Greece, Belgium, and Spain, etc. The religions represented were as numerous as the groups themselves. Each brought skills and a heritage; all had the desire to record their “ways” for future generations. They did not forget their past homes or their past.

"The state’s literature developed from this hodgepodge of cultures, social classes, races, and religions, plus the beauty and constraints of this specific place. The literature is of value; it defines this place, our place, and yet has universal themes and appeal.

"The topics and lessons included here offer a small sample of the literature created by early immigrants and their descendants."

Phyllis Moore is, as always, looking to include a plea for more ideas and names of authors.

.

Also from Phyllis Moore: A List of Books for Young Adults with Appalachian Themes and Writers From Phyllis Wilson Moore.

.

.

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 212

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

December 23, 2020

Department of Shameless Self-Promotion

-

MSW is teaching Novel Writing at NYU by Zoom starting February 24, 2021.

-

A Short Piece in A Journal of Practical Writing on Developing Character by Changing Proper Names

-

MSW sometimes blogs about the political issues.

-

Two new books:

.

.

Your New Reading Lists:

Ernie Brill's Abbreviated

History of Expanding the Canon

More Timely Poems by Hilton Obenzinger

Good Reading Online and More

Announcements & News

Shorter Reviews

Readers Write

Irene Weinberger Books

Phyllis Wilson Moore's syllabus of

West Virginian/Appalachian Literature

BOOK REVIEWS:

All Souls Rising and Master of the Crossroads by Madison Smartt Bell

Heartwood by James Lee Burke

Wild Seed and Mind of My Mind by Octavia Butler

We Were Legends in Our Own Minds

by Richard Cobb and Carter Taylor Seaton

Reviewed by Carrington Hatfield

When the Watcher Shakes by Timothy G. Huguenin

When the Thrill Is Gone and All I Did Was Shoot My Man by Walter Mosley

Locas by Yxta Maya Murray

Rembrandt's Eyes by Simon Schama

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

Marcella by Mrs. Humphry Ward (Mary Arnold Ward)

The Lightness of Water by Rhonda Browning White Reviewed by Donna Meredith

My original idea for this newsletter was to make a record of some of my own reading in hopes others might enjoy what I'd read. Increasingly, as other people joined in the conversation, I'd get new ideas for reading myself. This issue has lots of new ideas via Ernie Brill and his book lists . He has been developing these lists over many years of teaching and reading: books by and about women, African-Americans, Asians, and many other groups whose voices have only recently begun to be noticed in the mainstream media. Also in this issue are more poems from Hilton Obenzinger's "Chronicles" as well as reviews by Carrington Hatfield and Donna Meredith and, of course, my own explorations and pleasures--genre, historical novels, Mrs. Humphry Ward again, Rembrandt!

Finally, I wanted to share author Belinda Anderson's satisfaction in writing a series of super-local books about

Alderson, West Virginia. Anderson has written several excellent books of fiction for children and adults (see our review of Witchy Wanda here), and then a few years ago, she was invited to write a short book as a fund raiser for the nonprofit organization Alderson Main Street. The project turned into a yearly series of small books of anecdotes and history--all carefully researched--answering questions like "Does Alderson, WV have a leash law for lions?" and "Have there ever been any famous people at the Alderson Federal Prison Camp?"?

She says that one of the pleasures of selling books in non-literary venues like Visitors' Centers is that you get people who might not ordinarily buy your books. "At one of the signings," she writes, "someone had come in just to see an art exhibit at the visitors center, then apparently decided that buying one of these booklets was a good thing, since there was a line of people. As I prepared to sign her booklet, she asked, 'Did you write it?'"

I love that story: most of the people who ask me to sign their books are my friends and families and know darn well I wrote it!

Learn more about Belinda Anderson and her work at www.belindaanderson.com and https://www.facebook.com/AuthorBelindaAnderson . Check out a clip of a t.v. program about the Alderson series here.

TWO CHRONICLES BY HILTON OBENZINGER

Bookends

October 25, 2020for Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi

and Hozan Alan SenaukeIn summer 1968

I walk with my friend Alan

To meditate at the Berkeley Zen Center

We sniff tear gas in the air

And see police roaming the streets

Abbot Mel hosts the meditation

Gentle and kind, a saving soul in deep silence

No sirens, no nightsticks

The world in turmoil

Yet also glimpses of another way

No need to explain, simply say, “1968”

Mel opens the space on the wall for Emptiness52 years later

I return to the Berkeley Zen Center

To have lunch with Alan

Hozan Alan is now Vice-Abbott

And Abbot Mel is now 91

He is stepping down from his position

And Alan will step up later in the year

In a Mountain Seat Ceremony

I have not seen Mel for half a century

And we say hello and chat

The visit now and the visit then are bookends

To one shelf of an endless libraryWeeks later I watch on the Internet

The stepping down ceremony for

Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi

Retiring at long last

Stepping down as Abbot

He is tender and smiling

Joking sweetly

The world in turmoil

The virus digging into our flesh

And hatred and violence digging into our souls

But there’s also hope only days before the election

No need to explain, simply say, “2020”

Mel opens the space on the wall for Silence

Mysteries of Pandemia

December 2, 2020

My habits and desires have changed after months of isolation in Pandemia. I suddenly developed a taste for warm Diet Dr. Pepper soda. What a surprise. No ice, room temperature, a warm syrupy beverage some people might think is disgusting. I don’t know why this drink suddenly became my favorite. I also stopped watching cable news all the time. I would turn the TV on in the middle of the night to see if 3000 more votes were counted in Maricopa County or what wild demon would escape Trump’s mouth. But suddenly I was no longer glued to the screen. I am able to turn off the TV and live in silence for long hours. Silence is definitely a change.

I have been learning how to read again, skipping the words. I’ve also gotten into a habit of speaking with objects around the house. I greet my favorite spoon and fork, the spoon so large and oval and the fork with a great bulbous handle. I thank the Japanese bidet for electronically saluting when I walk into the toilet; the lid lifts up to attention every time, and I salute back. I reason with the roses in the backyard. I greet the redwood tree every morning. (It’s big and tall and hard to avoid.) I also have lengthy conversations with dead people – and I don’t think I’m the only one who does this. I don’t have any idea what day of the week it is. All days are the same. Which month? I forget to pay bills, and I’m not alone. I love my wife – we’re stuck together, trapped on the same lifeboat - and this is the time to work out all our problems. Or kill each other. Other couples do the same. This is why I’m learning how to read, but without words.

I had a dream within a dream in which I woke up to discover that I was a Black woman getting ready to go to work at the grocery store. This is odd because I’m descended from Polish Jews. So in this dream I went back to sleep and had a dream that I woke up to realize that I was a white teenage boy in high school in Tulsa. Each time that I woke up in the dream I marveled to discover my new body. Breasts, hair, youthful muscles, genitals, unfamiliar hands. I’ve never been a woman, much less a Black woman; and I’ve never been to Tulsa. Back to sleep, and I wake up again but this time as a young Chinese woman jogging through the park. This goes on for a while, as I turn into dozens of different people, until I finally wake up from the dream of a dream of changing into yet another body. I get out of bed and look at the mirror, greatly disappointed: I’m a shriveled up chubby old white guy, after all. I’m not as interesting as the people I met – or inhabited – on my world flesh tour.

REVIEWS

All Souls' Rising and Master of the Crossroads by Madison Smartt Bell

These are top notch historical fiction. Bell uses various point of views of people who make it through at least these two books of the trilogy. His best characters are a couple of white guys, especially the French doctor who is present and observing of most of the major action. He is the most understandable and morally attractive of the characters, and our best eyes. He becomes an aide to Toussaint himself and captures some of the mystery and power of that great general and nation-maker. Toussaint is an excellent horsemen, reader and reciter, mentor of children, especially boys, faithful to his wife, brutally pragmatic when he needs to be. He gets some point-of-view time as a prisoner in a cold French prison near the Swiss border, but even when he has the point-of-view, much remains a mystery, which I appreciate.

Other characters who get points-of-view include the maroon (runaway slave) Riau, who is also a commanding officer and vodou devotee. The women characters are deeply embedded in their sex-mother-rape victim roles. Only a couple of the white ones break out a little:

one is a murderer who has a religious conversion to vodou, and another whose house in town is the center for a lot of the story. She is a sexual adventurer and intriguer of considerable energy and agency.

The primacy of the consciousness of white characters is Bell's way, I assume, of inserting himself into the story. His one major foray into the consciousness of a man of color (Riau) works most of the time, but is occasionally awkward. Riau, for example refers to himself in the third person sometimes, in the first sometimes. It isn't hard to follow at all, but exactly what point is being made--something about a different way of placing oneself in the world-- isn't always totally clear. But you get used to it, as you get used to it as you get used to someone with an accent.

Bell has reasons for almost all of his bloody events and quirky voices: the novels are heavily researched, and he confesses in his introduction that his materials are mostly from French sources, including someone very like his French physican, and letters of Toussaint himself.

The gruesome battles and tortures are historical; so are the extremely racialized political factions (aristocratic white guys, wealthy mulattos, petit gens blancs who support the Jacobins and hate both the property-riich slave-holding groups, and the masses of black slaves.) The black ex-slaves are generally seen at some distance, which is too bad. One would like to hear their voices imagined, but Bell was probably wise not to to try to convey them. So he uses his French outsiders as his eyes and consciousness, and a few black people (Riau and Toussaint) who are unusually well educated.

The story does equally well (and this is unusual) in giving equal weight to the individual stories and to the events of history. In France, the king is beheaded, and England and Spain are attacking the French colony Sante Domingue (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic). Everyone on allsides is committing atrocities (one nasty piece of work murders his father, a famous torturer, by skinning him alive). The first novel begins with a crucifixion and continues on from there. Bell seems to delight in the details of the horror, but balances it as best he can with a little family love and military strategy. It is possibly the best combination of history and fiction I've read.

The original (1995) New York Times reviewer said "This bizarre and rich stew is the perfect stuff of fiction, whose subject is never reality but competing realities.... Beneath the social and political collusions and betrayals, the real subject of the novel -- and the ground-floor perspective for its understanding of history -- is the human body and its fragile relation to human identity under conditions of torture and mutilation." The whole review is at https://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/29/books/the-black-face-of-freedom.html .

The second book of the trilogy, Master of the Crossroads, follows Toussaint Louverture's early campaigns. It feels somewhat less well edited than the first volume (repeated phrases, some wandering), but it picks up momentum in the second half, getting better and better on Toussaint himself. A lot of politicial information and explanation is conveyed nicely in dialogue as characters drink rum and smoke cheroots. Characters we know very well by now argue what they think is likely to happen. The technique allows Bell to eschew a lot of summarizing. Battles are told economically and sensually.

I didn't think I'd read the third book, but now I think I might. I've gotten attached to the characters. Also, I keep thinking that now I might go back and read that history of Haiti that has always just seemed too tedious: this group rises and kills that group, then that group splits and kills each other, and on and on.

The trilogy is a big time commitment, but I'm finding it worthwhile.

Here's an interesting professor/historian's take on the novel:

https://h-france.net/fffh/maybe-missed/madison-smartt-bells-haitian-revolution-trilogy/

Rembrandt's Eyes by Simon SchamaIt took me two years to read this very large book, but I finally finished it. Schama writes very well, sometimes trying too hard for effects, but he has

done his homework.

It took me so long partly because it is very dense, but also because of the physical size. You can't take it to bed with you–if you dropped it, it would crush your chest. You can't curl up with it, because it needs support and strong light for all the wonderful pictures. So I usually read it at the dining room or kitchen table with lots of space to open it and peruse the art..

I had wanted for a long time to know more about Rembrandt, which this gave me, along with some solid perks: first, a little history of what is now the Netherlands, at least during the seventeenth century. If we think the Republicans and Democats hate each other now, take a look at the wars between sixteenth and seventeenth century Protestants and the Catholics. Second, there is a huge chunk of the book about Peter Paul Rubens who was what Rembrandt wanted to be: wealthy, highly honored, used for diplomatic missions, etc. Rembrandt's career ended in not-quite penury and falling out of fashion. Very sad--financial collapse as well as the death of his loved ones from the plague.

Then, of course, the pictures, and Schama's enthusiastic commentary on them. Almost every page has images, mostly in color. Very satisfying book, although when something takes that long, you feel you really need to start over again.

Marcella by Mrs. Humphry Ward (Mary Arnold Ward)

Marcella was published in 1894 and set 10 years earlier. Mary Arnold Ward was part of one of the great middle class intellectual families of England (her uncle was Matthew Arnold). She is often best known for opposing women's suffrage, and I've been dipping into a scholarly book about her called Behind Her Times: Transition England in the Novels of Mary Arnold Ward by Judith Wilt. This 2005 study has a lot of say about "valorization" and other concerns of university English departments, and I have to admit I'm having trouble reading it, but on the other hand, it's good to have someone who has read and thought about all of Ward's works.

Because I am a reluctant fan of her novels. She is a very late Victorian, and the world she writes about is, in fact, quite different from even George Eliot's and Charles Dickens'. Mrs. Humphry was a kind of conservative, and she did oppose women voting for members of Parliament, but she also said women should vote in local elections and she seems to have thought women should run educational institutions and medical ones.

Then there's the protagonist of this novel, the beautiful, talented,and passionate Marcella, a sort of combination of Austen's Emma and

Eliot's Dorothea Brooke. The opening sections about her girlhood are lovely: her parents dump her at school when she is very young, and she rarely sees them. In spite of having no money, she is couageous and indeed wild and difficult. When we next see her as an adult (this is when we realize how far we are from Early Victorians) she is in art school in London, quite on her own and hanging out with political radicals called "Venturists," who stand in for the real-life Fabians.

Then, unexpectedly (for her, not for readers of Victorian novels who know about these reversals of fortune), her disgraced father inherits substantial country property, and she moves in with him and her fascinating cold mother. Reluctantly she realizes she enjoys the beauty of the English countryside--and having an inherited position in the community. She thinks she knows better than the poor people themselves what they need, how they need to live, and makes egregious errors. She soon meets the squire next door who will eventually be a Peer and is presently running for Parliament, and he falls in love with her. Marcella is in love with the idea of her possibilities--and how she might use his fortune for good among the poor in the villages. So she pledges herself to the future Lord, getting his agreement to her plan for how to use his money.

Then--of course it was going far too smoothly--she meets another handsome young landowner, this one a radical in politics, also running for Parliament. He challenges her Lady Bountiful approach to the working people in the village, and soon she is torn between him and her intended. and we are off and running in that wonderful way of novels back in the day when you knew there were going to be major impediments but true love would (probably) triumph.

Aside from enjoying the pattern of the story and all the rich details of local characters and conflicts (there's a lot about poaching, which is an excellent point at which to enter into the meaning of property and class in the nineteenth century), what I really love is that Marcella goes out and gets a job. She doesn't sit home and wait--for anything. She engages in a series of mistakes and struggles, and her beauty and forceful personality do her more harm than good. The handsome radical landowner seduces her with his ideas, but she does not let him seduce her physically;

Marcella breaks off her engagement and trains to become a nurse. She works competently and well in London, serving people, bravely stepping between an abusive husband and his wife. Yes, she eventually ends up back on her property, and of course she eventually sees the value of the right man. I suppose this is conservatism, but Marcella's moral and physical adventures are gripping and exciting, and she only gives herself to her lover when she is strong and experienced.

The Reluctant Midwife by Patricia Harman

Patricia Harman, a longtime nurse midwife, has a good-hearted series of novels about midwives set in fictional Hope River, West Virginia. Harman has a clear, direct

voice– in this novel, the voice of a registered nurse named Becky Myers during the Great Depression, who has lost her livelihood. She goes back to Hope River, hoping for work, but she has in tow her ex-employer, physician-surgeon Isaac Blum, who is in an acute state of silence, immobility, and stupor. She cleans his teeth, tucks him into bed at night and generally cares for him. The nurse, Becky Myers, finds small and larger jobs, including helping her friend the local midwife, even though she is not comfortable assisting at births. Meanwhile, Dr. Blum begins to go out on veterinarian calls with the midwife's husband.

Becky gets a part-time job at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, one of the government-run programs for out-of-work young men that did projects in the park system and helped support their families through the lean years. Becky runs a clinic for the young men in the CCC, and over the course of the novel there are enormous physical challenges for her–serious illnesses and wounds to treat, drives through icy mountain passes, brutal births, an extremely dangerous pregnancy, and a terrifying forest fire.

The inner thread of the story shifts occasionally from Nurse Becky's point of view and her journals to the Doctor's journal, and we gradually learn why he has fallen into this mental apathy, and why he continues to pretend to be in it. Without sugar coating any of the situations, and with a number of sad deaths of characters we like, Harman brings us to a conclusion that isn't a huge surprise, but nonetheless is very satisfying.

We Were Legends in Our Own Minds by Richard Cobb and Carter Taylor Seaton Reviewed by Carrington Hatfield

Have you ever wanted to go backstage? We Were Legends in Our Own Minds is just the ticket you’ve been waiting for.

In their new book, memoirist Richard Cobb and co-author Carter Taylor Seaton tell the tales of Cobb’s career managing civic arenas, such as Charleston, West Virginia’s Civic Center and Huntington’s Civic Arena, among other. The book tells of his encounters with Rock and Roll bands such as Sly the Family Stone, Black Oak Arkansas, Elvis Presley, and many more. This book depicts what rock and roll meant to West Virginia and pays homage to the great rock artist era ’70 – ’89.

From Aerosmith to ZZ Top, Richard Cobb saw them all during his twenty- five- year career managing mid-market arenas where they played. He tells stories about eating Fig Newtons with Elvis on his private airplane, about his struggle with Sly Stone on and off the stage, and about his battles with protesting conservative Christians who hoped to scuttle a scheduled performance by Ozzy Osbourne. “We Were Legends in Our Own Minds” is a background pass to all these musical adventures.

“Richard Cobb’s memoir shines a bright spotlight on the early burgeoning concert venue scene. He helped usher West Virginia, especially, into what would eventually become: A state of Rock n’ Rock!”

-- Chris Ojeda, Lead guitarist/ vocalist with Byzantine

Music wasn’t the only type of entertainment that Cobb’s book details. He booked shows such as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, Holiday on Ice, and The Harlem Magicians.

So, what do you do when you find yourself living a life of rock and roll, as an Appalachian man born in coal country? Do you follow the crowd or do you shine among the best? Richard Cobb chose to be a part of the attraction, not the crowd. He booked many bands and famous celebrities we all know and love or at least remember! Photos in the book capture many of the memories.

This book immersed me into a life of rock and roll that I could have only imagined. Cobb and Seaton do a wonderful job of portraying what a life of rock roll looks like, especially here in the mountains.

“ We Were Legends in Our Own Minds” will capture the hearts and minds of any music lover and give them a peek into the behind the scenes they have always wanted.

The book is $19.99 and is available from Mountain State Press, www.mountatinstatepress.org, Amazon, Amazon and local bookstores and gift shops.

Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

This is an admirably written novel that didn't get to me emotionally. I read it because I've always meant to read a Stegner, and it appeared in the book (like the Madison Smartt Bell trilogy above) Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other) compiled and edited by Mark C. Carnes (Simon & Schuster 2001). I've been reading the Carnes book slowly, stopping to explore novels it mentions that I haven't read yet. (See my notes on it in Newsletter # 210.)

Angle of Repose has as its narrator, Lyman Ward, an historian himself, who is trying to put together a book, something like the book we're reading, about his

grandmother, via her letters, and simultaneously to create (like this novel we're reading) the world of the post Civil War Far West. The letters are, as best I can tell, lifted pretty accurately from a real woman's letters. The character is a Quaker and visual artist and very genteel, very drawn to Eastern culture (books, music, art, conversation). She leaves much of what she loves best, though, to marry an engineer who takes her to some pretty squalid mining camps and outdoor adventures, including some months in Mexico.

The story has lots of wonderful scenes and places, but Stegner wants it to be essentially the story of a failed marriage that is also a totally committed marriage. That works fairly well, although I feel that Stegner thinks he loves the woman, but really doesn't. She is in the end the little lady who says to the big heroic cowboy, "Don't leave me, darling," to which the hero says, "A man's gotta do what a man's gotta do." That is to say, in spite of his professed admiration for the woman, Lyman the narrator, and I believe Stegner the author, are all in for the man. For all of the woman's artistic and financial accomplishments (her book illustrations and travel articles often support the family), he presents her as trying to hold back, imprison, and change her husband. He has no real sympathy for gentility and not much for strong women.

The part I like best is the "real west." Stegner writes brilliantly of landscapes and mines and irrigation systems and the details and possibilities of Western life.

Lyman, the narrator, is largely wheel-chair bound and unhappy with pretty much everything in his life but his work. His curmudgeonly relationship to modern times (the 1970's) feels pretty silly from the 2020's. In spite of his suffering, I don't like him much.

Anyhow, another reader will no doubt like it, and I am glad I read it.

Locas by Yxta Maya Murray

Yxta Maya Murray is a law professor and part-time novelist, and Locas, published around 1997, got great reviews and was treated as if it were non-fiction about girls in a Mexican-American Los Angeles gang. It's gripping and readable, with a strong, simple structure alternating two young women's voices as they tell what happened to them at a crucial moment in their lives and in the life of the gang, or clika, the Lobos..

Lucia and Cecilia tell their stories of trying to find their places in a world of male privilege and male violence. Cecilia's brother (Lucia's lover) is the jefe of the Lobos. . It's set in Echo Park L.A., as it was in the nineteen eighties, and it offers an interesting picture of women striving for success in a world that is a disastrous outgrowth of poverty in two nations.

What it doesn't do--and I'm sure Murray would assert that she doesn't have to-- is give a full picture of that time and place and these lives. The two protagonists have each achieved something by the end of the book, however partial and limited the achievement. They are also both looking at a bleak future hollowed out by loss. The story is compact and narrow (making a point about their lives, of course). The problem with one's tendency to accept it as "real" because of the power of the voices is that the focus is too narrow to say much about anything but these two characters and about the big themes of poverty, male supremacy, etc. Anything not about gender, poverty, gang crime, failure of parenting, is scoured out. Any part of the "civilian" world is ignored. Even something like the cooking and food is only shown as something else the "sheep" girls do for their men. They don't savor food themselves, apparently. Even their clothes and hair to which they give so much artistic attention are sneered at.

Cecilia has a friendship, really a love affair, with an enemy gang girl that is rather lovely, and Lucia's ambition to be a jefa herself is interesting. But for me, so much seems left out that at some level I don't quite believe it: what about those girls who make an art of make-up? What about the who might actually have enjoyed reading (even if super hero comic books?) Doesn't someone occasionally get a job and leave--perhaps back to Oaxaca?