Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 206-210

February 12, 2020

Read this newsletter online in its permanent location Back Issues

MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Review of MSW's Their Houses in Southern Literary Review!

Marc Harshman suggests this poem by Barbara Crooker for when we are feeling low because of politics.

Looking for a high quality writing class in New York City? Try NYU's School of Professional Studies Writing classes--see catalog here.

Books for Readers # 206

In This Issue:

New Books, Announcements, and Events

Shorter Reviews

Notes on Recycling Fiction from Ed Davis

Good Reading Online

Announcements

Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

Irene Weinberger Books

Book Reviews:

Book Reviews, if not otherwise credited, are by MSW.

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

Urban Narratives by Ken Champion

reviewed by Sarah Katharina KayssFelix Holt by George Eliot

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest J. Gaines

Gone, Baby, Gone by Dennis Lehane

Fuzz by Ed McBain

Becoming by Michelle Obama

A Question of Upbringing by Anthony Powell

The Overstory by Richard Powers

Goshen Road by Bonnie Proudfoot

Link to review of The Dead and the Living by Hugh Seidman

reviewed by Burt KimmelmanBlood Lands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder

Women Talking by Miriam Toews

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

The Power of the Dog by Don Winslow

Everyday Chaos by David Weinberger

I like to be reading several books at a time. Sometimes I'm too tired to face a book with challenging ideas, so I read a calm procedural like Donna Leon's hymns to Venice via her laid-back and reflective Commisario Guido Brunetti. Sometimes I want to learn something about a subject or a person--I'm reading a book about Louisa May Alcott now, and I have ready-to-go one about Fruitlands, the utopian project where she lived with her Transcendentalist father Bronson Alcott and the rest of the family.

Last month I was flipping back and forth between two books of breathtaking distance from one another. The first was the wildly popular and best-selling....

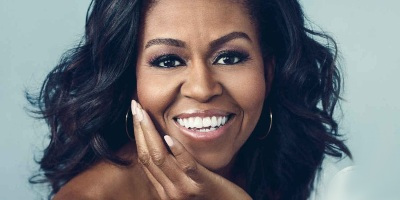

Becoming by Michelle Obama

The book was engrossing and well done on so many levels, but I have to say I probably loved the carefully written narrative of being a first family less than the story of Obama's growing up in a very middle class family on the South Side of Chicago. It was a family much like my own, and a family that made it easy for her to identify with the middle and working class families she met on the campaign trail in Iowa in 2008 and elsewhere. Her schooling, and her early work years, and her insight into the difference between achievement and money and doing work that is spiritually satisfying is all solid and reassuring.

The book is, in fact, reassuring on many levels. The structure is strong and highly polished with carefully laid in details that foreshadow coming events (I'm thinking of how she prepares and then tells of the assassination of Osama bin Laden from her point of view). She is also candid in her emphasis on her "village" throughout this book. That is, as first lady, as elementary school student with a bad teacher, she was never alone. She writes about the importance of her women friends, about her mentors, her mentees, and her large staff throughout her public career, including the team that helped with this memoir.

Plenty of public figures and authors give shout-outs to the people who supported them along the way, but Michelle Obama describes in detail and with respect the staff at the White House and a myriad of others who she sees not merely as support but as co-creators of her work and indeed who she is. This quality alone is worth reading the book: Americans are far too seduced by the ideology of the Lonely Hero. Obama speaks of herself as someone who doesn't like to be or work alone. How closely she feels herself woven into the groups around her is one of the most instructive things here.

She also presents in powerful detail what it is like to be a successful African-American in America–both the ordinariness of it--all the normal human fears and failures and sadnesses-- but also high accomplishment and pride--and the special challenges of being looked at as a representative of a race.

This is readable, instructive, and uplifting in all the best meanings of that word.

And I was so thankful to have it to turn to after reading a few chapters of.....

Blood Lands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin by Timothy Snyder

This history is about the part of Europe where fourteen million or so people were murdered between 1932 and 1945. This does not, by the way, count those hundreds of thousands who died in battle. One of Snyder's important points is that the reason we know as much as we do about the horrors of Auschwitz is that

Auschwitz was not only a death camp but also a work camp, and there were survivors. To hear personal stories, you have to have survivors, and few survived the murders in the Blood Lands.

Some Germans can make a case for not knowing what happened because only a tiny per centage of Nazi murders took place in Germany. Mostly the Nazis shipped those they believed to be "subhumans" to the Blood Lands for death.

Millions there were also killed by Stalin's consciously planned famines before the Second World War; more millions were simply shot in the head as they knelt by burial pits. These were Jews but also Poles and Ukrainians and many, many others.

One of the book's great strengths is that it makes horrible sense of how easily ordinary people--people like ourselves-- can join the killers in order to survive. We also learn to convert abstract ideals into mass murder. In Stalin's case, there was an abstraction of a greater good for the greatest number that turned into starving millions to death. Hitler had a ideology of a superior race ruling in glory over subhuman slaves.

Nor was it simply good guys versus bad guys. Politics became twisted and deadly: Lithuanians joined the Nazis to shoot hundreds then thousands then millions of the "subhumans" because they hated the Russians Brave partisans killed Jews after they fought the Nazis.

In prisoner of war and other concentration camps, people with a strong urge to survive ate corpses--and sometimes created a supply of corpses to eat. The appalling pervasiveness of all this is almost beyond understanding. The sheer numbers of murderers as well as the murdered should bring it home that it could be us and our friends and family.

Snyder handles all this brilliantly, but his book did not elicit despair in me. For one thing, it carefully distinguishes things: Hitler's vision, he writes, had an aesthetic basis (all those beautiful blond Aryans) and was insane. Stalin's vision in the beginning was rationality pushed to a horrible extreme (too many Ukrainian peasants? Starve 'em. Too time consuming? Then shoot 'em).

But the enormity of what happened in Poland and Ukraine and the Baltic States is clearly one of the things that human beings--a lot of us-- have proved capable of. It's looking less and less likely that we can put the brakes on the worst impulses of our species, but it isn't impossible. There are hopeful signs: slavery has been largely eliminated; many countries have at least an idea of caring for each other as family beyond the blood family. There will always be serial killers among us, but we can be better than our worst. Political systems can help, when they aren't being used to make us worse. Religion at its best can help. Individuals can make a difference, but it's important to recognize that there's no single thing that an stop the next Blood Lands, but many things.

Occasionally, Snyder refers obliquely to other atrocities in history: Hitler, for example, admired the United States for push through for lebensraum to the Pacific ocean, getting rid of native subhumans as it went. He considered that a model for Germany.

We have to think about that. We have to think about our high principles: was Stalin better or worse than Hitler for having a vague idea of making the world a better place for the majority? And how about those American blankets infected with small pox to clear away natives? How about buying people from Africa and stacking them chained on ships and tossing over the dead ones every morning?

How many are going to die from climate change as the side effects of untrammeled profit seeking? But, of course, comparing victims goes nowhere. What matters is knowing that we are all capable of both the worse and the best.

But, oh my, how horrific the worst is.

Goshen Road by Bonnie Proudfoot

Bonnie Proudfoot writes very beautifully–her mountains and animals and plants have the same vigor as the people in this a set of closely woven stories that create if not a conventional novel, then something just as good: a vision of mountain life from the late sixties through nearly the present among people who choose to live in the hollows and high fields of Appalachia.

One young man named Lux is dedicated to homesteading, wanting just his girl and his strong back to make a

place to live. This is long time American individualism and pride, and Lux's failure seems noble. Yet, subsistence farming isn't really a twenty-first century option. Everyone needs another job–logging in Lux's case.

What's remarkable to me about this book is that Proudfoot does not bewail the fate of people whose chosen lifestyle isn't working out. Nor does she bewail the bright girls who get pregnant and drop out of high school. She walks a narrow line in portraying the richness of this way of life without romanticizing it. People are unfaithful to one another, they have babies probably too soon. They often have narrow views, and they don't live up to their own ideals. She recognizes them as intelligent and creative and determined. And recognizes the pain of their collapsed dreams.

Some of the stories stand alone quite nicely, like the story of Billie's brief infatuation with a drifter/dope dealer/carny that ends in jail but is delightfully rollicking throughout. The long piece about Barker Mountain and how the dream of subsistence farming at the end of Goshen Road is probably the heart of the book, about struggle and dreams and love. It is also about the good people (Lux and Dessie and their family) versus some real losers, Wayne Barker and his road-destroying gang of drinking buddies. The destruction of the road becomes the focus of the story, and ultimately perhaps the whole book,

The final chapter has a nice description of change in one of the main characters. We've seen Dessie go from a passionate, competent girl and young woman through serious vicissitudes with her troubled but spiritually powerful husband. When he dies, she goes through a depression that leads her to spend half the insurance money on televangelists Tammy Faye Bakker and Oral Roberts, but she finally begins to find some new directions, repairing the home place, taking on babies to care for and a troubled older girl.

It's not everything you'd want for a wonderful character like Dessie, but it's a lot.

Everyday Chaos: Technology, Complexity, and How We're Thriving in a New World of Possibility by David WeinbergerThis David Weinberger book brings us up to date on his thinking. Weinberger has been a prophet for the value of the Internet for decades, and in this book he confesses that it isn't all good--that the voices of the 'Net haven't changed the world in the way he imagined they might. Commerce got the jump on us.

Still, his explorations of machine learning suggest a new, realistic kind of optimism. It forces us to face uncertainty, to accept that we know very little, and to feel awe. Bravo for his honesty and continued reading of the future and thinking about our present. He offers a whole world view, about getting older as well as confronting the vastness of computer generated learning and the use of vast conglomerations of data.

Leigh Buchannon in Inc. Magazine says, "Weinberger, for decades one of the most prescient and philosophical thinkers about the internet, here tackles the broader subject of how technology influences the way we understand and function in the world. Moving back and forth between ancient history and 10 minutes from now, Everyday Chaos explains that fixed-future ideas like progress and preparation are insufficient in the face of multiplying layers of complexity. Yet as our decision-making is overtaken by machines, it becomes possible to operate without our own hypotheses about what will work. Weinberger advocates for operating in a state of "unanticipation" in which we leave options open (think minimal viable products, agile development, and black swans). In this way of looking at the world, traditional strategy can be dangerous. Obscurity is your friend."

For the whole article, click here.)

The Silence of the Girls by Pat BarkerPat Barker is always worth reading, very solid, very Britishly confident of her competent prose and her story telling. This one is a spin-off/revision of The Iliad mostly from the point of view of Briseis. In it, as in her wonderful World War I trilogy, she explores war from the underside and unheroic.

To my taste, Barker is, oddly, least successful here in her protagonist's parts of the book. By giving Briseis a first person voice, Barker ends up with a woman who sounds thoroughly contemporary in her sense of self and desire for personal agency. Obviously you write a novel about the Trojan War to imagine and connect to the lives and experience of the voiceless– the women, especially the enslaved women– but by giving Briseis such a modern sense of self, the past seems to be lost.

Amazingly to me, she actually does a better job of that imagine-and-connect with Achilles himself. She uses short third-person-limited passages for him, and manages to make him interesting and concrete while retaining the mythological mystery.

There is no mystery about Briseis, and I have to assume Barker doesn't want there to be. Briseis is one of us transported back in time. The big gap for me is that while Barker imagines what it would have been like to be a slave in a soldiers' camp, she doesn't give us much of what it was like for the women when they were "free." Briseis actually seems to have more physical freedom in the camp of the Greeks.

As a writer, I wondered how she might have made Briseis more 8th c. BCE. She might have used third person limited, as she did with Achilles. Might Briseis have had some some interactions with the gods and goddesses? That's certainly in the Iliad. Part of what makes Achilles work as a character is his relationship with his goddess mother, who shows up out of the sea occasionally, always mourning him in advance! He yearns for her and is annoyed by her--very much Homer, and she's a real Greek goddess and a real mom.

Anyhow, this book gets better as it goes on, and, as I said, Barker is always worth reading.

For a review that accepts the feminism and explains some of the background, see The Guardian.

The Overstory by Richard Powers

I had trouble finishing The Overstory. It has been very popular, and it certainly has some beautiful passages and some strong action scenes. It also teaches some interesting things about the lives of trees. I definitely got the idea that trees are important and have mysteries that human beings haven't begun to address let alone understand.

But I felt so flattened by the constant preaching, and so weary of the repetitions. The review in the Guardian points out that there are multiple references to how some redwoods are older than Christianity. Oh, and I, like some other readers, had trouble distinguishing among the human characters, as in remembering which faithful friend/boyfriend was which.

I do admire the novel's ambition-- the very bigness of Powers's conception. Also, I could not agree more about the bleak picture of what we are doing to the soil and the old forests.

Powers manages a pretty good story line out of his material, but the politics seems constructed from slogans and superficial research (the Occupy Wall Street part, for example, is the merest sketch).

And he definitely romanticizes the trees. It occurs to me that he has made the trees (created in his novel as a collective, or perhaps a kind of planetary Oversoul). It is as if they were in all ways the opposite of human beings: giving, wise, welcoming, etc. And it should be noted that the trees are big plants, maybe the biggest, so easy to identify with. We all have a beloved tree. Shel Silverstein wrote The Giving Tree and then there was Dr. Seuss's Lorax speaking for the trees. In other words, trees are relatively easy to identify with. What about fungi and one celled life forms?

Who speaks for the volvox?

And one more complaint: one of the possible hopeful directions at the end is Artificial Intelligence. AI is is gathering all knowledge everywhere and will perhaps find the right answers for us. A lot to question in this theory, which is, in the end, the argument that technology will save us. (For a more complex look at these issues, see David Weinberger's book reviewed above). And if you set that hope beside the romanticized plant counterpart of human beings, you have ideas that are no necessarily wrong, but seem a little thin to me.

Still, if on the other hand, a mere hundred of the people who read novel learn that the earth is valuable for itself not just for us to use, and maybe even sentient in some way we can't fathom-- then it's a worthwhile book.

SHORTER REVIEWS

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest J. Gaines

Mostly highly entertaining, and it does what is advertised, which is touching fictionally on a lot of history. Miss Jane Pittman's life goes from the end of slave times to the height of the high civil rights movement. There is

wonderful specificity about Gaines's Louisiana and its people, including Creoles who won't have anything to do with anyone else of color; the ever-present Cajuns; and the odd "Sicilian."

The black poor, even after emancipation, continue landless and dependent on "master," and there is also insight into the limits this puts on white people, especially the men, who are so addicted to their power they don't see what's happening around them.

Gaines is also very good at giving hints of dialect with words like "Luzana" for the state and "retrick" for rhetoric. Jane herself is feisty and smart, creating for herself a successful life through hard work, mutual support with others, and some good luck along with the bad.

Felix Holt by George Eliot

I reviewed Felix Holt a long time ago for The Ethical Culture Review of Books. This reading, I was still struck by the portrayals of the two main women, Mrs. Transome and Esther Lyon, but I was also interested in the overbearing Harold Transome and minor characters like Mr. Christian and Mr. Johnson and also Denner, the faithful servant to Mrs. Transome.

Probably the least interesting character is the eponymous Felix Holt himself. Eliot admires him, but also presents him as another version of Harold Transome--both of them cut off their mothers from their life's work. Felix does it as an act of righteousness--stopping Mrs. Holt from selling homemade medicines of doubtful scientific value. I usually found myself on Mrs. Holt's side. She is a talkative hoot, and another charming long-winded character is the "little" minister Mr. Lyon.

Eliot wrote this book just after Romola and just before Middlemarch. It will never be my favorite of her novels, but it has funny scenes and the revelation of a great secret. Mrs. Transome's suffering is brilliantly depicted, and there is also the interesting effort by Felix to turn the rioters away from hurting other people.

And finally, Esther's choice--her moral strength-- is the real happy ending.

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

This novel, based grimly too-close to real events at a now-closed reform school for boys in Florida, is vivid and has an interesting change at the end that didn't seem necessary to me. The events were plenty shocking on their own: no more stimulation needed. I wonder if it was a story that really needed to be fictionalized?

On the other hand, I was totally pulled into it, and fully understand the impulse of a serious novelist to get into such a story–the torture and murder of boys, with, in spite of brutal beatings for everyone, far worse treatment for the black kids.

The Power of the Dog by Don Winslow

So it appears Winslow does a lot of research, so there's a fair amount of accuracy in this, in part, but on the other hand, his characters are fictional, and he doesn't have all the facts up to date, but apparently the drug cartel bloodbath is real enough. I doubt I will read the second two books of this enormous trilogy, which is just too much for me. I did finish The Power of the Dog, though.

What I see here is history mixed with fiction and a lot of super macho game playing that skips, of course, almost all of women's experience except terror and sex. All normal work life is skipped.

If this exceedingly lukewarm review makes you want to read WInslow, get a more even-handed idea of the books from NPF and the Seattle Times:

https://www.npr.org/2019/03/03/698645059/the-border-is-shakespeare-for-our-times-seriously

Check out Burt Kimmelman's review of Hugh Seidman's The Dead and the Living.

Gone, Baby, Gone by Dennis Lehane

A typical Lehane. You've got to enjoy Boston and a lot of torture and gore. He takes his time, writes heart-wrenchingly of children in danger. This one is about a group of monster child molesters. Lehane really knows what to do with this repelling material. As long as you know that you're going to get lots of twisty, twisted violence, you'll get your moneys worth. Like much commercially successful genre fiction, Lehane repeats his themes and tricks, but, again, he fulfills his part of the bargain.

Fuzz by Ed McBain

I've been trying to educate myself a little over the past couple of years on genre novels. Lehane is always on list of crime writers, and so is Ed McBain. The writing in this one wasn't terrible, but after someone like Lehane, the story is so light the book practically flies into the air. It felt to me like a scenario for a network TV show with a few metaphors tossed in. It features various recurring characters, apparently already established in previous novels, and some murders of cardboard politico-types and a few henchmen and other supernumeraries. So it wasn't hard to read, but melted Ike a macaron.

One notable thing: this was published in 1968, with apparently no awareness of a near-world-wide revolution underway. The characters are more into good-humored wise cracking than current guy cops and P. I.'s who spend so much time suffering over their dark military pasts and vulnerable daughters.

Urban Narratives by Ken Champion reviewed by Sarah Katharina Kayss

"From the poignant first story, "Art House," and the inventively funny yet sad "Verstehen,: through to the gritty realism of the urban college stories and the often bedevilled clients of a flawed East London analyst...his work is amazing."

A Question of Upbringing: Book 1 of A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony PowellI had an odd reaction to this first volume of Powell's big work. I was often irritated, but never enough to stop reading, and after a while, I began to take pleasure in something--not the snobbish unpleasant people, but something more like the flow of it. It was a little Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels--a sort of river of event and emotion and scene rather than events or plot. Something about how our lives flow. On the other hand, the Ferrante novels grabbed me deep inside, and Powell's didn't. The world of Naples was less constrained, bigger and more colorful.

There is a moment when the narrator of A Question of Upbringing is reading À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, and I thought That's it, the focus on time memory, the unexpected changes in individuals over time. Three rivers, then: : À La Recherche, Ferrante's Neapolitan quartet, Powell's Dance.

But this first Powell book was low spirited compared to the other two: thinner, like blue milk.. I expect I'll read more later, to see if my opinion changes, but it makes me miss the richness of Proust, the symphonic cacophony of Ferrante.

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

I just reread Little Women--so much good stuff, but also angel-in-the-house propaganda. However, it undermines its own ideology, and I think the undermining is what most readers remember: Jo March's (and also Amy's) struggles for self and to work in the world.

But you also remember poor shy Beth dying! Dare any heart be hard enough not to break down the middle?

Women Talking by Miriam Toews

I really really liked Women Talking. I had never heard of Miriam Toews until this, from a list of #metoo novels. It is almost all dialogue, as a group of spirited Mennonite women living in great isolation are raped by their own men, and then try to decide what to do next. The narrator is a man, one who has left the community and then returned. He is desperately in love with one of the women, and is asked to write down what they say, as the women are not allowed to learn to read and write.

I came to like these people so much, and really wanted a happy ending, but if the ending is not conventional, it is strong, and grows out of the blossoming of the women's communal thinking through talk. This is truly a group novel whose themes and specific character create its style.

And shockingly based on real events.

ESPECIALLY FOR WRITERS: Notes on Recycling fiction from Ed Davis

Ed Davis writes that his story "Bend the Knee," published in Still: The Journal (#30, Summer 2019), "was salvaged from a failed novel Old Growth. After OG was rejected by a university press and an agent I respect, I embarked on a process of literary recycling. Since I'd already written a sequel to OG, I basically folded several of the best chapters of OG into the sequel as dramatized backstory.

"This involved expositional underpinning and summary of the missing chapters as the narrative moves backward and forward in time between OG and its sequel. As a result, the older material has gained renewed energy in the context of the brand-new, untried story. It feels like it's working. The process hasn't been easy—but neither is turning a novel chapter into a stand-alone short story, either. The true test of success will come when my beta readers weigh in." Read the story "Bend the Knee" here.

GOOD READING ONLINE

A wonderful memoir piece by poet Burt Kimmelman called "Carroll Capris," about growing up Jewish in South Brooklyn among small time Italian gangsters This first appeared a few years back in the Missouri Review.

Diane Simmons, Fulbright Fellow to the Czech Republic and much more, has an excellent piece on the Communist Regime in Czechoslovakia at Lit Hub. This an excerpt from the longer piece published Fall 2019 in Missouri Review as "Nobody Goes to the Gulag Anymore."

Jane Lazarre's new piece in Lilith on Tillie Olsen.

Suzanne McConnell on Kurt Vonnegut--read a sample in The Nation

Latest issue of Persimmon Tree is up.

Two hilarious/depressing articles about making best sellers: One is by Sarah Nicholas about how the rich game the best seller business (https://bookriot.com/…/buying-books-onto-the-bestseller-li…/), and the other is by Brent Underwood about how a fake book ("Putting My Foot Down") became a best seller on Amazon with the sale of three books (https://observer.com/…/behind-the-scam-what-does-it-takes…/…).

"Ten great Novels that rewrite history..."

New in A Journal of Practical Writing: Recycling Your Old projects--Notes from Ed Davis.

A poem for those of us who are hard-of-hearing: "Disclosure" by Camisha L. Jones

Excellent Review of Unlikely Friends by Judith Moffett

See our review here in Issue# 204.An article about editors and editing by one of my teachers, Lore Segal.

Article on how Larry Brown made himself into a writer.

See our review of Larry Brown's novel Joe.A List of Books for Young Adults with Appalachian Themes and Writers From Phyllis Wilson Moore.

Some online suggested in previous issues of this newsletter:

A short story "What's Good About the End" by Naomi Feigelson Chase online at The Brooklyn Rail.

Two of Suzanne Martinez's latest short stories: "There are No Whys;" "The-Cinderella-of-Sunset-Park"

George Lies's story "Rafaello's Night"

Ed Davis's “Bend the Knee” at n Still: The Journal. It’s an excerpt from the unpublished novel Old Growth.

And finally, Lewis Brett Smiler's story "The Care of Freedom." York Times!

ANNOUNCEMENTS AND NEWS

The Stones of Lifta by Marc Kaminsky is now available

The poems of Marc Kaminsky’s The Stones of Lifta address the heartbreak of a history torqued and twisted by fear and hatred, but this poet’s heart remains unbroken, alive, responsive, and attuned to a painful dissonance. He consents, humbly and bravely, to abide with the suffering of both Israelis and Palestinians, to align himself with both his heritage and his empathy, so that the indissoluble contradictions of that conflict become, ultimately, nothing less than the paradox at the heart of being fully, vulnerably, honestly human. —Richard Hoffman

New from Blair Mountain Press: Victor M. Depta's What They Yearn For:

In the tradition of elderly lady sleuths like Jane Marple, Maud Silver, Sharon McCone, and Mrs Polliffax, comes Dr. Ethel Gooch, who is intrigued by the apparent suicide of the wife of the English Department Chair....

Beyond the Stone Eagle Gate by Jane Ellen Freeman is now available on Kindle.

In 1893, David, age fifteen and an orphan, strives to grow into manhood after escaping a brutal indentureship. When he is hired at a grist mill in a small Tennessee town, life looks promising—until someone puts the empty cash box by his bed. He flees. He won’t be tied, locked up. Never again. He runs through a thick forest and stumbles onto an old road. A creaking gate startles him in the darkness. Two stone eagles carved of white marble perch on high pillars. He shivers, the eagles familiar as in a dream. At the end of the cobbled drive, moonlight frames a mist-shrouded mansion. Desperate and exhausted, he breaks in and discovers an astonishing library. Furniture, covered and spectral, crowds the room’s center and bookshelves soar into dark shadows. Cold and in pain, David sinks into the warmth of a cushioned chair. As he sleeps, he does not see a shimmering light drifting down a curved, iron staircase. The light approaches, hovers, and as David stirs, disappears. Has he been lured into a trap or a refuge?

What They Yearn For by Victor Depta now available!

In the venerable tradition of elderly lady sleuths Jane Marple, Maud Silver, Sharon McCone, Mrs. Pollifax we at Blair Mountain Press are pleased to introduce Dr. Ethel Gooch (we like the odd and slightly uneuphonious name), a professor of English at a university in eastern Kentucky. She and Aubrey, a local student, are intrigued by an apparent suicide of the wife of the English Department chair.

Carol Gaskin's Editorial Alchemy continues to be highly recommended by my students and colleagues for full service editing.

Kelly Watt's Mad Dog--published in the USA for the first time!

Don't forget Roundabout by Elaine Durbach!

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 207

March 30, 2020

Read this newsletter online in its permanent location Back Issues

MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Colson Whitehead Caroline Sutton William Makepeace Thackery

Books for Readers # 207

Free e-books!

Especially for bored people stuck at home

who always meant to read one of my books:Seven Meredith Sue Willis books

(e-book versions)Free until April 21, 2020

Click on books above, or go to Smashwords.com,

search for Meredith Sue Willis,

choose your book, and follow instructions.

First Publication! An Article about an Indie Author Going Home to South Africa!

Phyllis Moore's syllabus for a course on West Virginia literature: ROOTED IN SOLID GROUND: JOURNEYS INTO APPALACHIAN LITERATURE.

Learn more here.Blair Mountain Press to celebrate their 20th anniversary is Donating to OVEC (Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition).

Do you need to digitalize old books and/or old floppy disks?

A good company I've used for turning my hard copy books that were written on typewriters (yes, yes, I know...) into .pdf or .doc files, is Golden Images, LLC.

Or, if you need aged floppies converted to usable files, try https://retrofloppy.com/. They charge $12--$20 a disk (unless it's some really bizarre format).

In This Issue:

New Books, Announcements, and Events

Shorter Reviews

Good Reading Online

More Recommended Books

Articles and Links Especially for Writers

Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

Irene Weinberger Books

Book Reviews:

Book Reviews, if not otherwise credited, are by MSW.

Roundabout by Elaine Durbach

The Stones of Lifta by Marc Kaminsky

The Cutting Season by Attica Locke

Wonder by R.J. Palacio

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens reviewed by Carole Rosenthal

Mainlining by Caroline Sutton

Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackery

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy

by Heather Ann Thompson reviewed by Ingrid HughesThe Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Miami Blues by Charles Willeford

These are strange days for twenty-first century Americans who have grown up feeling relatively safe, at least from things like infectious diseases and the disruptions of war on our territory. We are used to feeling sorry for the faraway destitute victims and refugees, and we often join in mourning with the families of soldiers killed fighting our nation's unnecessary wars.

Now, however, we have begun to be aware of a widening gap between the wealthy and the rest of us, and to notice how many Americans depend on emergency rooms for health care. Still, for the working middle classes, these have been gradual realizations leading mostly to low-grade anxiety.

And now we have front-and-center the fear of coronavirus, Will this finally connect us to the sorrows and sufferings of the rest of the world?

We are hunkered down here in a small city on a commuter line into New York City, worried and glued to our screens like everyone else with internet access. We do our jobs online, and we have video chats with our kids in Los Angeles. We now have a New York City nephew with (we hope) a mild case of the virus. We have friends who are nurses and doctors on the front lines. We are healthy so far, but with a looming sense of emptiness and uncertainty. When I'm feeling upbeat, I try to see this as a reminder that change and unknowing is what is before us all the time.

That's it for imparting wisdom.

Meanwhile, may anyone reading this have hope and good health.

And as always, lots of things to read!

Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Having read Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad this past September, not long after Toni Morrison died, I’m hoping he’ll write many more stories like this one, carrying on the thought-provoking interpretation of African American lives that Morrison carried on from James Baldwin and others. Like Morrison, Whitehead is unconventional in many choices he makes in telling his stories. One of

his most unconventional choices in The Underground Railroad is his use of magic realism: real trains chug from one subterranean station to another on the secret route north to freedom. This bold device has gotten lots of attention from critics, but he departs from convention in subtle ways, too.

By foregoing the convention of numbered chapters, Whitehead emphasizes the chaos and uncertainty of the enslaved characters’ lives. Chapter numbers imply order; but the lives of slaves were liable to disruption at any moment. According to their master’s whim, enslaved men, women, and children could be killed, tortured, or separated from family to live with the misery of not knowing where loved ones are or even whether they are alive or dead.

Cora, the main character, never learns what happened to her mother, who apparently escaped the plantation, leaving ten-year-old Cora behind, still a slave. Not until near the end of the novel do readers learn—though Cora does not—what happened to her mother.

Cora’s sense of abandonment never leaves her, but it helps make her strong. The anger the abandonment inspires in her, combined with the hope inspired by her mother’s accomplishment, fuels Cora’s desperate determination to win her own freedom. After first rejecting a fellow slave’s invitation to run north with him, she soon changes her mind and says yes—as the narrative tells us, “This time it was her mother talking.”

In her efforts to escape, Cora is opposed by Ridgeway, a resolute slave catcher whose sidekick is an African American boy named Homer. In one of the many ironies in the story, Homer keeps a notebook in which he faithfully jots down Ridgeway’s business accounts and the slavecatcher’s commonplace observations about life. Whether Whitehead intended it or not, I read this slave-catching team as a send-up of the familiar combination of the White hero and the Black sidekick—seen as early as Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn; all too often in 1980s and ‘90s action movies like “Lethal Weapon” and “48 Hours”; and continuing into twenty-first century movies, such as “The Green Book” in which the gifted Black musician’s role basically gives the audience cause to admire the heroics of the star of the movie, the musician’s White bodyguard.

Ridgeway is obsessed with catching Cora because he’d failed to catch Cora’s mother. He is Cora’s arch enemy; and she is his. The ongoing struggle between these two characters, Black slave versus White slavecatcher, is the story’s most intriguing and suspenseful element, especially in the context of the many Black-White twosomes of our literary and film history. The passions that feed their struggle form the heart of the story.

Whitehead implicates most of his White characters in the oppression of Blacks. For example, a young medical student augments his meagre income by stealing corpses from the graveyard, most often stealing Black corpses because their graves aren’t well protected and because the authorities pay little attention when Black families complain. The student’s gruesome work is singular, but not an isolated example of Whites exploiting African Americans in the name of medical science. Cora learns of freed Black women being sterilized and of men and women being experimented on without their consent or awareness of the harm being done to them. Even manual laborers like Ridgeway’s father, a blacksmith who shapes hot iron into the “tools of progress” (including shackles for slaves), form a vital part of the oppression.

Among the few exceptions to this exploitation are the White station agents who operate the underground railroad, and they suffer dreadful punishment for their dangerous work. Whitehead’s rendering of their characters is understated. He presents them as ordinary men doing what they feel they should; yet his modest depiction, implicitly attributing humble stoicism to these characters, makes them seem all the more heroic.

Both his fanciful underground trains and his underplayed portrayal of heroism contrast with another of Whitehead’s ironies, his horrific “Freedom Trail,” an aisle of trees hung with lynched runaways, their bodies in various states of decay. Again, I’m not sure of all he intended, but I wonder if this move mocks Boston’s Freedom Trail commemorating the American Revolution, as the Revolution aimed to win freedom only for White men.

Entitling the final section of the novel, “The North,” is a final example of the wry slant to so much of this novel, as Cora, still on the run from slave catchers, climbs into a wagon headed west. The wagon is driven by an older ex-slave who bears a horseshoe brand, a brand readers recognize from earlier in the novel as identifying slaves from a particular plantation. The horseshoe shape also harks back to the Ridgeways, the blacksmith father and slave-catcher son. As the story’s conclusion, this passage sounds a haunting chord: the lasting scars and mechanisms of slavery stay with its survivors even as they move into the future.

Also check out out review comparing Whitehead's Underground Railroad to Octavia Butler's Kindred and our review of Whitehead's Nickel Boys

Mainlining: A Memoir by Caroline SuttonCaroline Sutton's previous book Don't Mind Me, I Just Died (see our review here), was a series of thoughtful and moving essays about things as varied as a young child's perception of paintings in a museum; the suicide of a young friend; road trips; tennis; and the lives and deaths of beloved dogs. Those excellent essays included a lot about Sutton's family, but this new memoir is a fully shaped whole work that moves through its material with growing momentum.

Again, the center is Sutton's family, especially her mother, an immigrant from England to Philadelphia's Main Line suburbs, and her father, who is from an old (and documented) American family. It's is about a particular class of family aspirations and values and tastes, about private schools, kilted skirts, entertaining, too much drinking, dogs, and houses and what they mean to us.

Toward the end, it builds toward a well-earned and satisfying climax of discovering that you can love even difficult people. Sutton's father is largely silent, an alcoholic who never missed work and was a survivor of one of the great WWII ship bombings in the Pacific. Her mother is judgmental and demanding, with precise rules of behavior and aesthetics.

Perhaps the star of the book, aside from the fine consciousness of the narrator, is the houses: something I think of as an especially British quality (or maybe I just love Howard's End). Sutton's girlhood home, the lovely house and garden in Bryn Mawr, is her mother's special expression. The memoir is also, however, about the home Sutton makes with her husband and children in Dobbs Ferry. New York, and about her father's camp in the Poconos with its uneven flooring and semi-functional kitchen. Finally is the the senior complex where Sutton's mother spends her last years, first in her own apartment, then in assisted living, then in skilled nursing.

This is a wonderful, low-key, moving book, sturdily built, taking us on life paths at once familiar and fresh.

The Stones of Lifta by Marc Kaminsky

Marc Kaminsky, the prolific poet, therapist, and student of life review, has a new book of poems that face squarely his relationship with Jewish history-- in this collection, not the European history of pogrom and Holocaust, but rather the history of Israel.

The poems are about Lifta, a village near Jerusalem that was emptied of its Arab inhabitants during the early wars to establish the nation state of Israel. Kaminsky was inspired to write the poems from a documentary film about Lifta made up of interviews with Arabs

and Israelis. Each poem is an evocation of some piece of the complex story. Many are dramatic monologues and some of the most difficult ones to read (for emotional content, not style) are in the form of dialogues.

One of the best (and best in a fine book like this means something only incrementally better than the other poems) is "The Coffee House in Lifta," based on the life-histories of two real people. In it, two men sit on the floor of the ruin of what was once the village's coffee house. The Arab says to the Jew,. "And you believe..."

that if you and I return in Memory

to the place where my world came to an end,

we can make our two stories one?

The distance between the two men in the poem, willing to talk, but choked by sorrow and loss and bitterness is at once vast and terrifyingly intimate. The Jew was born in a Displaced Persons camp, and for him, part of the story is about a beloved and admired uncle, a refugee from the Holocaust, who became a member of the militia that destroyed Lifta and this very coffee house.

I've awakened from the dream in which he was my childhood

Hero, in the coffee house at Lifta, he nullified the God

my father kept alive in a death camp....

The poems are all emotionally complex yet told in plain language. Kaminsky, the author of 8 previous volumes of poetry (see our review of A Cleft in the Rock) as well as books on reminiscence and life review and Yiddeshkeit, always writes with deep seriousness and a near-sacred respect for both his subjects and his readers.

The penultimate poem, quoted here in full, is short and told in everyday language, and is profound and powerful:

Disbelief

And then at dusk, when the white

and yellow Jerusalem stone breathes in the light

and the city softens as if the haze of gold

that rests on all things brought out

the blessed state bestowed by the gaze of the Eternal,

it seems improbable that we cannot live

in peace. The call from the Al-Aqsa Mosque

and the cries from the Wailing Wall

are melodic step-brothers that are sounded

together and ascend as a contrapuntal sound.

Does God unravel our prayers

and place them on separate rungs?

Roundabout by Elaine Durbach

It is always a pleasure when a novel gets better the longer you read, and that it what happened as I read Elaine Durbach's Roundabout. This one fulfills its promise.

In this case, it is a relatively simple situation–a woman wakes to find the love of her life dead beside her in bed. She then spends the first weeks of her loneliness keeping a stiff upper lip, getting through her anger with something akin to humor– and then, as she begins to clear the house in order to sell it and give the proceeds to her lover's adult children, she gets caught in the web of memories.

Gradually we discover what is special and particular about those memories. It turns out that Sally Paddington and Felix Barnard, both white South Africans, have lived much of their lives in the United States. They have also known for decades

that each was the other's most passionate and fitting love. Yet their lives and some stubborn refusing part of each of them has kept them from being together. They've both had spouses, two for Felix, with a child from each, and Sally was married once, and lost a baby of uncertain parentage. They've both had professional success, and they come together occasionally--finally, in late middle age, to live together permanently till death separates them.

It's a fascinating premise, the missed opportunities, the continuing passion, the late-life joining--not shocking or edgy, but very real. The longer I read, the more bits and pieces of the story that came to light, the more explanations and revealed motivations, the more intensely I felt for Sally and Felix.

Especially after Felix's daughter Joanie comes to the house to be with Sally, there is a gathering intensity that lights up the novel's world as Sally learns a final few important things about Felix and at last admits how deeply she'll miss him–and how much he has enhanced her life.

It's the best love story I've read in many a year.

Also see "Indie Author Goes Home" in this issue about Durbach's book tour in South Africa.

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens Reviewed by Carole Rosenthal

Very readable, and perfect for me during a time when my mind was scattered yet I wanted to be distracted: great and very specific writing about the natural world, and I liked the young character Kya. It has a great sense of place--the marsh--but at the same time, the story is pretty formulaic.

There were no characters built except for Kya. Not that you didn't root for the oh-so-kind Tate and his dad and also the likable store owner, Jumpin', but these were stock figures, and the real love story between Tate and Kya held no surprises. Nor did the villainous but banal Chase.

The ending, well. . . . just undeveloped summary, not believable and not satisfying. Any exploration of what it meant that Kya had actually killed Chase that could possibly have been interesting was instead passed over, just another detail of the summary years. Its surprise to the reader who didn't expect it is not even taken into account--what did it mean to Tate about Kya after all these years?

I'm glad I read it. Owens can write fully visualized and enchanting detail about this marshland, so it was fun to read, and fast, yet given its premise, pretty predictable.

One question: is it believable that a seven-year-old can survive total abandonment in the marshes with no money or friends (although eventually Tate and Jumpin' and his wife)?

(For another take on Crawdads, click here.)

SHORTER REVIEWS

Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson reviewed by Ingrid Hughes

I've been reading Blood in the Water, a fat volume on the Attica uprising and the cover-up that followed it. I had a general idea of what happened, and some hazy memories. The detailed story is sickening, frightening, horrifying. At points I had to stop reading. The barbaric cruelty of the hundreds of NY State Police and the prison correctional officers who went in to end the uprising was very much like a pogrom, killing for the sake of killing a vilified group.

Vicious racism.

Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackery

Just finished Vanity Fair, which I hadn't read in a long time. It has some travelogue padding in the final quarter, but the ending itself is satisfying. Becky Sharpe, after repeatedly losing her gambles, actually succeeds by her own lights. (I chose not to believe that she poisoned the fat gourmand Jos.

Sedley.) Amelia and Dobbin have finally married and have a baby.

The question of whether or not the narrator is reliable strikes me as worth thinking about--he constantly hints all the worst about Becky, but there is a real case to be made (stipulating that she did not poison Jos.!) that her only major sin is pushing away her child. I admit this is thoroughly damnable by 19th century standards--and, I suppose, by twenty-first century standards as well, We still want to believe our mamas always think of us first.

Even though Thackery seems to be in love with Becky himself, he stacks all the cards against her, trying to give her no redeeming characteristics--except charm, of course, and in the end all readers seem susceptible to her charm.

He even downgrades her for liking all the odds and ends of bohemian types in her rooming house/hotel: acrobats and sales people and singers and gamblers and students--I thought they sounded great. But their linen is filthy. And Becky drinks with them.

One thing I totally forgot until this rereading is that faithful Dobbin finally rebels against his servitude to Amelia, and of course once he toughens up (becomes a man?), she finally sees him as a possible mate. Thackery is brilliant and amusing, but of course is subject to that cool British nineteenth sexism and racism and jingoism.

But, it doesn't stop me from loving the book, even as Thackery can't top himself from loving Becky.

The Cutting Season by Attica Locke

This novel has a wonderful setting for a murder or two: a former Louisiana plantation being used for tours, performances, weddings and other events. Main character Caren Gray, the manager, also grew up there, and one of her ancestors died under mysterious circumstances on the property.

The sale of the plantation and what that means to the white owners and the largely black staff shapes the novel, but there also are a couple of murders in two different time frames and plenty of subplots about Caren and her daughter and her daughter's father. Is there anything left between Caren and her ex? Is the death of Caren's ancestor in some way related to the present time murder?

Lots of race and class--a book that explores the strange intimacy between black and white people in the South--told from a black perspective. The cops bumble; Caren sleuths and endangers herself and those she loves.

It's more psychological novel than mystery, but excellent reading either way. Caren's ancestor and the black sheriff who tried to investigate his death bring in a whole other layer that is badly undervalued in our history lessons--the hope and despair associated with Reconstruction.

Wonder by R.J. Palacio

This middle grade children's novel (kid characters are ten through fifteen), was published in 2012 and has been wildly popular: translated into lots of languages, still selling briskly eight years later (Auggie would be 18 now!) It is told in several first persons, all middle school and high school kids.

Auggie is a kid with severe facial malformations and a humorous, loving, protective family. The plot is basic: everyone eventually agrees it's time for him to start going to a real school, he does, he has lots of problems there, but makes friends and "frenemies," and by the end of the year wins over almost everyone and becomes himself far less dependent and infantilised.

The triumph is equally his and that of his big sister who realizes she, too, is capable of wishing she could be free of his face, and his friend Jack, who makes a stupid mistake and has to earn forgiveness, and Auggie himself who keeps wanting to go back to being a little kid not a big one. Anyhow, with the exception of one family, almost everyone is redeemed or forgiven, or comes out better than they started.

And it manages to be just about totally unsentimental (well, except for the old dog dying). Written with passion--a good book.

Miami Blues by Charles Willeford

I got the idea to read this from a list of best American crime novels. I didn't like the beginning, but got into it after a while: protagonist Hoke Mosely, who keeps having his false teeth stolen or lost, is a shlub, and the psychotic bad guy Freddy is wonderfully funny–the oddity here is that Freddy lights up the pages. He is optimistic and enjoys his life far more than the good guy. Everyone is convinced that skinny hooker Susan is dumb, but she does just fine in the end. Anyhow, I ended up chuckling over it.

And it ends with a recipe! The article in crimereads.com called "The Life and Times of Charles Willeford—Miami's Weird, Wonderful Master of Noir" is worth reading.

MORE RECOMMENDED BOOKS

Healing Mind, Healthy Woman by Alice Domar (learn more about her here)

NEW CURRICULUM OF WEST VIRGINIA LITERATURE

Phyllis Moore's syllabus for a course on West Virginia literature.

ROOTED IN SOLID GROUND: JOURNEYS INTO APPALACHIAN LITERATURE

See syllabus here.

(From the introduction)

"Many of the seventeenth and eighteenth settlers of West Virginia came from Scotland, Ireland, England, Germany, among other European locales, to ports on the eastern coast of North America. They moved on to (what was then) the mountain wilderness west of the colonies.. These settlers and others brought their history and heritage, memories and stories, as well as the drive to be independent land owners. They were not here first or here alone, however. They massacred, uprooted, or in the best cases merged with Native Americans. Some brought with them, or later purchased, African Americans as slaves.

"The mountains’ mix grew to include increasing numbers of ethnic groups from countries such as Italy, France, Poland, Greece, Belgium, and Spain, etc. The religions represented were as numerous as the groups themselves. Each brought skills and a heritage; all had the desire to record their “ways” for future generations. They did not forget their past homes or their past.

"The state’s literature developed from this hodgepodge of cultures, social classes, races, and religions, plus the beauty and constraints of this specific place. The literature is of value; it defines this place, our place, and yet has universal themes and appeal.

"The topics and lessons included here offer a small sample of the literature created by early immigrants and their descendants."

Phyllis Moore is, as always, looking to include a plea for more ideas and names of authors.

ESPECIALLY FOR WRITERS

Indie Author Goes Home by Elaine Durbach

For an author in search of book buyers, writing what we know has an added bonus: Readers who knew you way back are likely to be supportive, especially if they expect to recognise places and possibly the people in your story. And ownership offers them boasting rights no other buyers can claim.

Half of my novel Roundabout is set in my home country, South Africa. The main characters meet at Rhodes University, where I was a student, and Sally, the narrator, ends up living in gorgeous Cape Town where I spent my teens and began my career. Playing on all that, on a recent trip back, I appealed shamelessly for help to old high school friends, to college alumns, and to cousins. The result: three talks, two book club visits, two book parties and a radio interview. It was so much fun! The only frustration was taking time to talk and read excerpts when there were so many people to hug and catch up with.

Perhaps the most memorable back-home moment came at the one event attended by an old boyfriend, the guy who inspired the main male character, Felix, whose death triggers Sally’s soul-searching journey back in time. I tried to be subtle and resist the urge, but failed. I said, “For those wondering how much of Roundabout is true, let me tell you this: Felix is alive and well – and in this room.” An audible “Huh?!” swept the room and every head swiveled, including his.

“It was my best disguise,” he told me later, grinning with a mixture of pride and embarrassment. I’d given him an early copy. He bought another two.

An article about editors and editing by one of my teachers, Lore Segal.

Someone sent me a link to an interesting article in a self-publishing blog about choosing titles for your book. It's good for traditionally published writers as well as self-publishers. There is more stuff on my Resources for Writers page too.

Check out Reedsy.com for free lessons and information, and to hire publishing specialists (and lots more information. Some sample articles:

• What to look for when you're looking for an editor.

• What can authors expect from their fiction editor?

• What to expect from your book cover designer,

• How to work with a typesetter or layout designer?

ANNOUNCEMENTS AND NEWS

Spring List from Spuyten Duyvil Publishers

News from Blair Mountain Press

Blair Mountain Press has always been an advocate for the environment and people of Appalachia, especially the coal fields of southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, eastern Tennessee and western Virginia. They published Coal: A Poetry Anthology in 2006 to give voice to the people of the region; and in 2002 Azrael on the Mountain, a book of poems by Dr. Victor Depta protesting mountaintop removal coal mining.

While coal is declining as an industry (30% of the energy produced in America is based on coal; 50% in 13 states), the use of natural gas is now the preferred substitute. The problem with its use, however, involves fracking, which further decimates the environment in Appalachia. The folks at Blair Mountain Press are opposed to hydraulic fracturing.

To express this opposition and in celebration of our 20th Anniversary, 10% of the proceeds of all Blair Mountain Press sales during the year 2020 will be donated to OVEC (Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition).

Blair Mountain Press

124 East Todd Street

Frankfort, Kentucky 40601

502-330-3707

www.blairmtp.net

New novel by Rita Quillen!

Rachel King news:

"In January, Green Mountains Review published my short story "A Deal" both online and in print. Someone who values hard work and modesty comes into conflict with someone who values accomplishments and connections. It's my favorite story I've published.

"Ms. Aligned, an anthology series that features women who write from male perspectives, published my decade-old story "CD Player," an homage to Elliott Smith, in their third issue. You can read a excerpt of the story here and buy the anthology here. I'd probably wait until after the crisis to buy, however: it's available only on Amazon, where workers have been overworked and/or are coming down with the virus.

"For the past two years, I've been the managing editor at Ruminate Magazine. For the current issue, I wrote the editor's note. If you're interested, you can buy that issue here."

New Children's Recording by Dr. Lori Brown Mirabal

New Children's Recording by Dr. Lori Brown Mirabal, Classical Vocalist

To learn more about the singer, her career in opera,

and her work with children, click here.

Check out Suzan Colón's memoir with recipes!

Cherries in Winter is a multi-generation memoir using

author Suzan Colón's grandmother's recipes as an anchor.

GOOD READING ONLINE

Illustration by Bill McConkeyNew (to me!) and cool: AO3 (An Archive of our Own-- huge collection of fan fiction). Read an essay from The Atlantic about the rise of fan fiction from Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope (who wrote poems about Gulliver's long suffering wife) to the present.

Terrific non-fiction piece by Suzanne McConnell at The Brooklyn Rail. Also see her piece on on Kurt Vonnegut- in The Nation

Barbara Crooker's updated poems

Innisfree 30, the spring 2020 issue of the Innisfree Poetry Journal, is now available at www.innisfreepoetry.org. In this issue, Innisfree takes a “Closer Look” at the work of Jack Ridl with a number of poems from his collections and presents new work from twenty-seven other contemporary poets.

Burt Kimmelman's "Carroll Capris," about growing up Jewish in South Brooklyn among small time Italian gangsters This first appeared a few years back in the Missouri Review.

Diane Simmons, Fulbright Fellow to the Czech Republic and much more, has an excellent piece on the Communist Regime in Czechoslovakia at Lit Hub. This an excerpt from the longer piece published Fall 2019 in Missouri Review as "Nobody Goes to the Gulag Anymore."

Jane Lazarre's latest piece in Lilith on Tillie Olsen.

Recycling Your Old projects--Notes from Ed Davis.

Excellent Review of Unlikely Friends by Judith Moffett. See our review here in Issue# 204.

A List of Books for Young Adults with Appalachian Themes and Writers From Phyllis Wilson Moore.

Some online readings suggested in previous issues of this newsletter:

Short story "What's Good About the End" by Naomi Feigelson Chase online at The Brooklyn Rail.

Two of Suzanne Martinez's latest short stories: "There are No Whys;" "The-Cinderella-of-Sunset-Park"

George Lies's story "Rafaello's Night"

Ed Davis's “Bend the Knee” at n Still: The Journal. It’s an excerpt from the unpublished novel Old Growth.

Lewis Brett Smiler's story "The Care of Freedom." York Times!

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 208

May 16, 2020

Read this newsletter online in its permanent location Back Issues

MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Issue Dedicated to the Memory of John Birch

You are now able to buy books at Bookshop.org where a percentage of every sale goes into a pool that is distributed every six months to brick-and-mortar small bookstores. You may also choose your local favorite bookstore to make the profit!

The Bookshop.org site says "By design, we give away over 75% of our profit margin to stores, publications, authors and others who make up the thriving, inspirational culture around books! We hope that Bookshop can help strengthen the fragile ecosystem and margins around bookselling and keep local bookstores an integral part of our culture and communities. Bookshop is a B-Corp--a corporation dedicated to the public good."

MSW has her own storefront at Bookshop.org that shares profits with bookstores and pays the author a little. If you are a publisher or writer, you can set up your own store front free!

In This Issue:

New Books, Announcements, and Events

Good Reading Online

Anthologies of Appalachian Writing

Irene Weinberger Books

Book Reviews:

Book Reviews, if not otherwise credited, are by MSW.

The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander

The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee

Fruitlands: The Alcott Family and Their Search for Utopia by Richard Francis

The Coughlin Series by Dennis Lehane:

The Given Day

Live by Night

World Gone By

Review of Buried Seeds by Donna Meredith, Reviewed by Edwina Pendarvis

Snapshots: a Collection of Short Stories by Eliot Parker

Wayland by Rita Sims Quillen

Robert Elsmere by Mrs. Humphry Ward

Jack of Shadows by Roger Zelazny

As I prepare this issue of Books for Readers in mid-May 2020, we are still in the strange and terrible throes of the Coronavirus. Tens of thousands of people dying, fewer among the wealthy, affluent, and middle classes who can comfortably self-isolate, but the stress and unknowing are global, with a special terror in this country over decisions at the national level. I just read an excellent summary of how the virus spreads, and what behaviors are most risky. It is clear, rational, and practical--and to that extent, reassuring.

In many ways, my personal life has continued in its familiar course: I spend a lot of time taking walks around Orange and South Orange, New Jersey; cutting grass; gardening. I continue to write and teach (via video); see my grand children (also via video, but that's how I see them most often anyhow). I am deeply missing excursions into New York City to see friends, visit museums, and just generally enjoy the vitality of the streets. My friends there, however, are even more shut in than I am. I am also following how my other home: West Virginia and the rest of Appalachia are having their own distinct reactions to all of this.

I know people who are unable to read fiction at this time, and others (and I'm closer on the continuum to this group) who are stuffing themselves with fantasy and thrillers and Victorian literature in book form and television. Take a look below at some of what I and others have been reading.

But first, I want to begin with the obituary of a lovely gentleman who used to write a column for this newsletter.

-- MSW

In Memoriam

John Birch, a former British military officer and chosen New Yorker, was in one of my novel-writing classes at NYU a number of years ago. He was one of the ones who brought more to the class than he took away: more life experience and critical ability. He died at the beginning of April 2020.

He was a graduate of the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst in Great Britain. Commissioned into the South Staffordshire Regiment, he served as an infantry officer in Northern Ireland, Germany, Egypt and Cyprus. He left the British Regular Army as a captain and joined the Army Reserve Royal Engineers bomb disposal unit.

He then for 38 years worked in major public relations companies in the United States, Britain, Australia and Malaysia. He was a senior vice president at Burson Marsteller, and before he retired in 1996, was director of development at Ogilvy Public Relations in New York City. During his PR career John worked on assignments in 42 countries.

An avid writer of fiction, nonfiction and verse, John published in the US, the Middle East and South East Asia. In 2002, as Jonathan Linn, John and his wife Lynn published a thriller set in Malaysia and Thailand, Dadah Means Death,. In his final years, John posted dozens of stories and personal essays in his blog "Storyboard," still available online.

For several years he also wrote a column for this online newsletter about e-readers and e-books. Here's sample: Books for Readers Archive 151-155.

He was a delightful man whose passing leaves a gap for many, but most especially for his wife Lynn (Marilyn) Yates Birch, his children, step-children and grandchildren.

Review of Donna Meredith’s Buried Seeds by Edwina Pendarvis

West Virginia’s state motto, Montani Semper Liberi, translated “Mountaineers are always free,” is a bold claim and only somewhat true. But Donna Meredith’s new novel, Buried Seeds, features two women willing to take the risks necessary to make such sentiments closer to the truth. The backdrop for the novel is the recent news-making teachers’ strike in West Virginia. Angie, a dedicated science teacher, is asked to take over union leadership duties. She accepts, not realizing how her new role will affect her family nor how her family—including her long-dead great-great-great grandmother, Rosella, who’d been a suffragette—will affect her leadership.

Two issues test Angie’s commitment to professional and personal ideals—how to handle union matters, most importantly whether to encourage members to strike in a state where teacher strikes are illegal, and how to be a good wife, mother, daughter, grandmother, and sister. Her husband Dewey is furious at her acceptance of union leadership. He has applied for a job with the FBI, and he’s afraid Angie’s role in the strike will cost him any chance for a job with the Bureau. Aside from being at odds with her husband, Angie’s worried about her daughter, who is a single mother with a

baby; she’s worried about her aging father, whose mild dementia is worsening; she’s not getting along with her sister; and she’s not sure how her infant granddaughter, born with a hearing impairment, will fare.

The author’s depiction of relationships among four generations living under one roof shows real empathy for the demands and rewards of an extended family living in close quarters. This understanding comes through clearly in dialogue between family members. Their back and forth is natural and lively.

Angie and Dewey’s dialogue shows the widely varying degrees of anger and fear, love and commitment they feel toward each other. Through-out their story, Meredith keeps readers teetering, unsure—just as Angie and Dewey seem to be—about whether the marriage will survive the troubled times the couple is experiencing. Such convincingly realistic dialogue, showing both the precariousness and the depth of their devotion to each other, constitutes one of two difficult balancing acts the author presented herself in this novel. The other balancing act has to do with another married couple, Rosella and her husband, Jack.

As we learn from Angie’s reading of Rosella’s memoir scrapbook, Rosella was born and raised on a farm in Harrison County, West Virginia, in the early 1900s. She had a real talent for drawing, which her mother encouraged and her father decidedly did not. When Rosella was fifteen years old, her father began pushing her to marry a man she didn’t love.

Her story really begins with her marriage, at age fifteen, to a different man. Partly to escape her unhappy home life, Rosella marries Jack, a handsome charmer whose roots are in Harrison County but who makes his home in San Francisco. In California, Rosella’s move to San Francisco opens up a new life: giving drawing lessons, selling her artwork, and joining the women’s movement for the right to vote.

Rosella’s commitment to political action and to art is tested by a personal life fraught with even more serious problems than Angie’s; and, unlike Angie, she has no nearby family members to help her cope with loneliness and worse. Her husband, who works for the railroad, is often away on business and is unfaithful to her, though she doesn’t know that at first. Rosella’s friends become her emotional support.

Meredith’s ability to balance conflicting truths is as evident in her portrayal of Jack as it is in her portrayal of Angie and Dewey’s relationship. Jack’s solutions to problems he himself creates not only put Rosella’s life in peril, but cause her the greatest heartache a mother can suffer. While there’s never any question as to his dismaying lack of moral character, Meredith doesn’t succumb to what was must have been tempting—to present Jack as just an uncaring SOB. She shows him as deceitful, weak; misguided; and selfish; yet sincerely contrite, and even capable of heroism. Creating a character with terrible flaws but with redeeming qualities that make him come to life meaningfully within the context of a marriage adds to the emotional and intellectual appeal of Rosella and Jack’s story.

One of the most exciting events in the book also takes place in Rosella’s lifetime, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Meredith’s account of the quake includes familiar observations—the earth shifting up, down, and sideways; explosions of gas mains; and fires erupting all around. But her close-up view includes less familiar details as well. One of the most surprising to me was two soldiers’ summary execution of a grocer for price-gouging.

Meredith’s ability to frame exciting, often tragic events within a realistic social and psychological context yields a page-turning yet plausible narrative about two heroic but “ordinary” women from West Virginia. This fast-paced, thought-provoking novel adds another book to her series of fictional and nonfictional accounts of women’s lives as they intersect with a particular time and place and strive for greater equality and freedom for themselves and others.

Wayland by Rita Sims QuillenWhat happens when a sociopath comes to a small Appalachian community during the Great Depression? Someone who is widely read, a natural artist with the pencil, an excellent raconteur? And oh yes, a man with a penchant

for young girls. Nothing good, of course, and yet there is a great deal of good in this novel, Quillen's second. It is loosely linked to her previous novel, Hiding Ezra, and Ezra himself makes a brief appearance at the end. The main characters include his sister and daughter.

One way to read this is as a portrait of a depression era community and what a sociopath might do to it--especially to one family, Eva, an artist herself, and passionate caretaker of many, but especially of her motherless niece Katie, whose beauty stuns strangers. Eva's husband Andrew is trying to make a living as a generally lonely outsider in a tight community.

Another way to read it is that the Devil comes to Wayland and the inhabitants react in a variety of ways--usually not telling each other what shameful thing they have seen or thought about. This repeated refusal to tell each other what they have seen or guessed (and no one ever considers bringing in the authorities) creates a magic atmosphere, some tone of horror, of an unstoppable force of evil. Still you have faith in Eva's courage and Katie's love of her family, and even in Andrew's ultimate good sense. There is something that makes you know that the righteous will eventually triumph.

It's a good story, and Quillen does a marvelous job of creating the several ways of reading it. Her good people are interesting, especially Eva, whose occasional short diary chapters are eloquent and gripping.

But in the end, her finest creation is the self-named Buddy Newman who she never tries to explain but only offers to us whole. There are hints of why he is as he is, but he remains mostly a mystery, a dark influence over a community who brings out their secretive sides and manages to separate even those who love each other.

His departure at the end opens the other characters to good luck, better relations, new hopes.

Robert Elsmere by Mrs. Humphry Ward (Mary Augusta Arnold Ward)This novel published in 1888 was debatably (if pirated editions taken into account) the

biggest best seller of the nineteenth century. It was admired by Henry James but disliked by Prime Minister Gladstone, and hardly known today, let alone read. I had largely stayed away from Ward's novels, mostly because I'd heard of her reputation as an anti-suffragist. I thought she was a kind of nineteenth century Phyllis Schlafly. She did believe that if women joined the dusty marketplace of ideas as voters, they would lose their moral influence. And toward the end of her life, she began to say that women should be able to vote in local elections.

In fact, she was part of an intellectually deep and subtle intellectual family (her uncle was Matthew Arnold, her nephew Aldous Huxley), and while she isn't George Eliot, she writes very well, everything informed by her broad knowledge of history, literature, theology, and issues of her day.

In Robert Elsmere she also creates at least one young woman character who goes beyond anything Eliot did with women's professional possibilities. Rose, one of three sisters central to the plot, is a talented violinist who goes to Berlin and London to study, and from all reports in the novel is powerfully devoted to her music and highly accomplished, even to a professional level. She is also beautiful, charming, and quite the difficult little diva-in-training. Her love affairs are important part of the story–but Henry James, generally a fan of the book, thought Rose's story line never gets woven sufficiently well into the rest of the novel.

The book is, indeed, more discursive (and long!) and less neat than we tend to like now, but no one seemed to care much in the late 1880's and early 1890's. What I like is that, although we don't know if Rose will continue to perform after she marries, she is certainly presented as a serious artist, unlike, say, George Eliot's Gwendolen Harleth who dearly wants to express herself artistically, but is a lazy amateur who in the end has only her beauty and a disastrously unhappy marriage. Rose is not only truly accomplished, but she ends up with a very appreciative and supportive (and wealthy) fiancé. Of course, we don't see him in action as a husband.