Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 219

January 23, 2022

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

New story online by MSW: "Fan Fiction: Paradise Lost"

at the Maryland Literary Review

Scenes from The Mutual Friend; image from Murderbot series; Carolina DeRobertis; World War II Cruister; Kendra James

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue # 219

Reviews are alphabetical by author, not reviewer.

If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSWGood Reading Online

Notices of New Books & AnnouncementsBook Reviews

Genre Selections

Department of Danny Williams

Book Recommendations and Reader Responses

Especially for Writers

Irene Weinberger Books

Book Reviews

The Overlook and Nine Dragons by Michael Connelly

The Gods of Tango by Carolina De Robertis

Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

Time and Tide by Thomas Fleming

The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love’s Prophet by Lawrence J. Friedman Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Admissions by Kendra James

Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez

The Color of Magic: Discworld by Terry Pratchett

An Act of Remembrance & Other Mostly True Historical West Virginia Stories by Randy Safford Reviewed by Danny Williams

All Systems Red, Artificial Condition, and

The Cloud Roads by Martha Wells

We are in a moment of setbacks on the socio-political fronts, a time of un-welcoming weather, and, of course, pandemic. I am thankful for dry days for walking, but we mostly stay in. I seem to be very busy with Zoom meetings for my political and literary groups, and I'm teaching online, but there is a staleness that settles around my shoulder from all the huddling indoors and the bad news. It helps me to remember we are all sailing in this leaky, funky old ship together.

Also that the days are getting longer.

For me, reading history gives a welcome perspective on now with information and stories about times that were far worse than these, and for some very fresh good news, look at some suggestions below for really good online readings and new publications mentioned in the announcements,

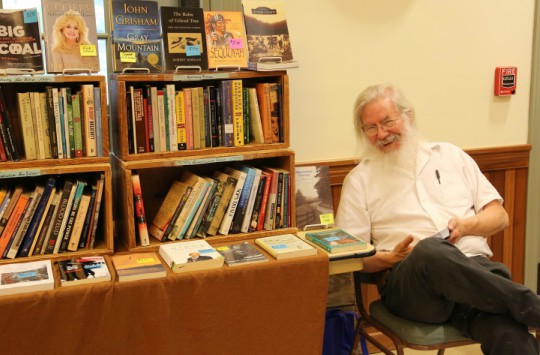

This issue also offers some materials and places to submit for writers, as well as the new Department of Danny Williams. Danny is an editor with lots of ideas about how to make your writing better--he was the editor for my 2002 novel Oradell at Sea.

And then, of course, there are the books, starting with Dickens (Our Mutual Friend) and including a brand-new just-published novel called Admissions about life in a New England prep school for a student of color,. and a novel I had missed by the ever-wonderful Carolina DeRobertis, The Gods of Tango. Plus a lot more--reviews by Joe Chuman and Danny Williams and a new-to-me fantasy/science fiction writer, Martha Wells.

REVIEWS

Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

This was written in 1864–1865, and is the last novel Dickens completed. I loved it on so many levels– the language; the easily visualized funny and violent scenes; the unusually rounded characters for Dickens, people who change, although one apparent change turns out to be a plot trick.

Bella in particular is one of Dickens' best snobbish pretty girls. She stays nineteenth century femme, but also develops into an energetic and self-motivated adult woman, even if she gives lip service to being the angel in the house. She's the real protagonist far more than the mysterious "mutual friend" of the title and plot. Dickens's ideology continues to insist that the Ultimate Purpose of Woman is to love (husband and baby), but he seems to have learned at least something about women from his own love affairs and, perhaps especially, from having daughters.

Bella's first sign of a saving grace (aside from beauty, which is never undervalued by Dickens) is how she enjoys her rather silly and passive old dad. Fathers and daughters are an important theme in this novel. The four (or more) daughter-father pairs include Bella and old Pa; Jenny Wren and her Child; Pleasant Riderhood and Rogue Riderhood; and of course the highly romanticized Lizzie Hexam and her father Gaffer.

Bella's soul mate John, however, is a pretty stunted character with an appalling upbringing. He is unappealingly in how he tests Bella and everyone around him. He is a damaged man with too little experience of good human relations, sneaky and distrustful. Most of this, though, is not examined but turned into plot material. Direct exploration of souls was never Dickens' strong suit.

But who cares. If you don't like John, there are a few dozen other delightful characters to follow. One of my favorites is Bradley Headstone (yes, Headstone) the school master obsessed to madness with beautiful, illiterate Lizzie Hexam. What a magnificent self-torturer! Then there is Eugene Wrayburn, the languid bored gentleman who also loves Lizzie but can't imagine any approach to a woman of Lizzie's class except seduction. He is eventually saved by Lizzie Hexam's emotional and physical strength.

The Golden Dustman Noddy Boffin and Mrs. Boffin, wildly popular a hundred fifty years ago, are fun but not my favorites. My favorite is the equally over-the-top but somehow more believable Jenny Wren, the semi-crippled dolls' dressmaker. There's a good-hearted victimized old Jew Riah, said to have been inserted to balance out the evil Fagin from Oliver Twist.

I was struck by how cinematic this is--or perhaps I only mean easily visualized. There is one tiny scene in a pub where two men sitting side by side start simultaneously leaning, just a throwaway scene, but one that would be very funny on film. There are many moments that burn into your mind: the rising water in the locks on the river, the sudden appearance of Rogue Riderhood in the door of Bradley Headstone's classroom.

But mostly, as I think about the novel, I just smile with pleasure at the ever-articulate Dickens people.

More: Philip Hensher has an excellent 2011 review of the novel in the Guardian .https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/sep/23/charles-dickens-favourite-mutual-friend Also take a look at this appreciation in Time by Radhika Jones: https://entertainment.time.com/2012/02/01/counting-down-dickens-greatest-novels-number-5-our-mutual-friend/

Admissions by Kendra James

Admissions begins light and humorous--told by a thirty-something woman with a full memory and enjoyment of the popular culture of her high school years. Her teen world was about instant messaging and Livejournal and role playing with people around the world. She writes Buffy fanfic and has a huge poster on her wall of Orlando Bloom as Legolas in Lord of the Rings.

She is also the first black legacy student at

the Connecticut prep school Taft where her father, a scholarship student, went in the nineteen-seventies. The first half of the book is mostly a flashback prep school story--a memoir with many names changed, but not the names of the institutions. But the frame of the story is the narrator out in the work world with a job recruiting students of color to independent schools.

We are told immediately that she has mixed feelings, and as she goes back in time to her experience, we learn why. Still, the first half is mostly funny. She has a moderately racist roommate, but she and her best friend Yara (Black, Lesbian, and a recruited athlete) get rid of the bad roommate. There are high jinks and discoveries--but the narrator becomes increasingly aware of the institutional racism toward her and her fellow students of color, many of whom are on scholarship or recruited for various skills. The narrator, however, is not on scholarship,and her parents are working hard to give her the so-called Taft Experience that is her legacy.

In the second half, she pays more and more attention to the way Taft thinks it welcomes Black students and other students of color, but in fact gives them no protection against a particular kind of wealthy kids' white privilege. There are some nice distinctions between what she knows now about white privilege and systemic racism and what she didn't know then--as a fifteen year old hanging on for dear life in a place where the talk was liberal and the walk was punitive for everyone who wasn't part of the elite.

And Legacy or no, the narrator realizes she is not part of the elite.

She gives credit to the teachers of all races who cared, and she includes a least one white student in the group that begins to meet after a clueless racist rant is published in the school newspaper.

Part of me wishes she had gone all the way mixing the fun and the seriousness in novelistic form, but James intends to have immediate impact on the current landscape. Her insights are crucial at this time of awareness of police murders and, especially, of how wealth has accumulated for the rich of one race (and how that wealth was accumulated) while even the affluent of the other race struggle with mortgages and second jobs.

It's a unique angle on what we are experiencing today, and a book that you can't stop reading.

Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez

March 18, 1937. A natural gas leak caused an explosion that killed more than 295 students and teachers.

I read Phyllis Moore's review in this novel newsletter Issue #217, and wanted to read it for myself.

I'm so glad I did. It's a gripping story, and once you're gripped, you're wrenched around and gob smacked. Tough stuff: the historical event is a gas explosion at a public school in the East Texas gas fields where almost 300 people were killed. More savage in the story, though, is the twisted rattlesnake ball of racism and sexism and general brutality that is lived before and after the explosion.

It is written from the point of view of eighteen and nineteen year old protagonists plus seven year old twins. The twins' father, main character Naomi's step-father, is the villain, although Perez insists on giving him explanations if not excuses and occasional point of view sections. Naomi, who shares with Cari and Beto a Mexican American mother, is dark-skinned while the kids are pale. Naomi and the twins go to the local "white" school where the twins fit in easily, especially as they are brilliant and beloved of their teachers. They read encyclopedias when things get dull. But Naomi's is an anomaly at the school because of her brown skin. She is never really accepted as white, and the teenagers (who have some group point of view sections) debate her looks and her morality. The boys fantasize privately and together about having sex with her.

Naomi, meanwhile, falls in love with Wash, a young black man from "Egypt Town." Wash is from a striver family who want him to go to college. What ensues has lots of beauty and and lots of danger, mostly from the stepfather, and then, in the end, almost everything bad that could happen happens.

I wanted the people I liked to come out alive, and I sometimes felt that Perez's choices were arbitrary--that things could have gone any way at any point. I suppose Perez would say Yes, exactly that's how the world works, but I felt mildly manipulated a few times.

Mainly, though, I deeply admired the book..

The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love’s Prophet by Lawrence J. Friedman Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Vogue authors abounded on college campuses in the 1960s. Names such as Herman Hesse, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts and Jack Kerouac were among those at the top of the list. For students poetically inclined there were Alan Ginsburg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, among many others. But for me the premiere writer was the social psychologist, Erich Fromm. Fromm authored more than 20 books, and starting at the age of 16 when I entered college, I devoured them all. For a depressed and lonely teenager, Fromm’s humanistic psychology that valorized the “productive personality,” whose character is molded out of social experience and active engagement with life spoke to me in ways that were inspiring and life changing. Though I have moved beyond his thought, I am forced to admit that no writer has more profoundly influenced my life, both in terms of framing my world view and anchoring my values than has Erich Fromm.

Lawrence Friedman’s The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love’s Prophet, is a prodigious piece of scholarship. Friedman is a professor in Harvard’s Mind/Brain/Behavior Initiative and has written texts on such psychological

luminaries as Erik Erikson and Karl Menninger. The title of the current work recognizes Fromm’s multiple roles as psychoanalyst, social philosopher, political activist, prolific and phenomenally successful writer and social prophet.

Erich Fromm was born in Frankfurt in 1900 and issued from a long line of prominent rabbis. Himself an orthodox Jew, steeped in Talmud and Chasidic folklore and song until he was 26, Fromm began to universalize his world-view through exposure to the thought of Hermann Cohen the famed neo-Kantian philosopher. Fromm, who was attracted to older women, was seduced by his analyst, Frieda Reichmann, eleven years his senior. They married and subsequently divorced, but it was through Reichmann that Fromm gained an appreciation for Freud, whose thought remained central to his life’s work. In 1929, Fromm joined the Frankfurt School of Social Research, a group of eclectic and skeptical Marxist scholars, Theodore Adorno and Max Horkheimer, the most distinguished among them. It was at the Frankfort School that Fromm, developed what would become the centerpiece of his theoretical work for the remainder of his life. That work centered on an attempt to fuse Freudian psychoanalysis with Marx’s social critique of capitalism, particularly ways in which the capitalist mode of production distorts human character, and transforms human beings into mindless consumers and conformists, thus robbing them of their humanistic potentials.

In order to do this, Fromm abandoned orthodox Freudianism’s central focus on man’s biologically-based instincts for sex and aggression, and replaced them with what he referred to as “social character.” In short, one’s psychological orientation and personality are molded by interpersonal relations. This created the opportunity for the development of different personality types such the “authoritarian,” “dependent,” “sadomasochistic,” “productive” pwersonalites, as well as others.

His revision of Marx was no less controversial. Rather than elaborating on the mature Marx of Capital, with its focus on economic determinism and mainstays of the communist movement such as the dictatorship of the proletariat and the historically mandated role of the working class, Fromm revived and expounded on the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. Here he transforms Marx into a proto-psychologist who elaborated on the alienation of man from his labor, himself and his fellow men. The Manuscripts of 1844 points to a humanistic and socialist utopia, which reinforced Fromm’s own Messianic values gleaned from the Jewish tradition.

In 1941, Fromm published his most important volume, Escape from Freedom, which attempted to analyze the compelling power of Nazism and its appeal to the German populace, though Fromm’s social psychology could be applied as well to strains of conformism salient in American capitalism. Fromm’s central thesis is that freedom generates anxiety.

Freedom, though it has brought him independence and rationality, has made him isolated and thereby, anxious and powerless. This isolation is unbearable and the alternatives he is confronted with are either to escape from the burden of his freedom into new dependencies and submission, or to advance to the full realization of positive freedom which is based upon the uniqueness and individuality of man.

This brief passage exemplifies the binary nature characteristic of Fromm’s thought; man either lapses into authoritarian obedience or moves ahead to claim his maturity, productivity and happiness. For Fromm, the latter is achieved through the positive unfolding of our potentialities, our human capacities for love, reason and productive work most of all. It is this unfolding, and the society it prefigures that comprises the acme of Fromm’s vision, which he refers to as “humanistic socialism.”

Before a falling out with Adorno, Fromm relocated the Frankfurt Institute to Columbia University in 1934, where he secured a teaching position, and then later at Bennington College and Michigan State. All the while, he engaged his work as a practicing analyst, helped to found the William Allison While Institute, had an affair with Koren Horney, even as he analyzed her daughter, and developed working friendships with Arthur Schlesinger, Margaret Mead, and David Reisman, among other intellectuals. And he continued his writing that enabled him to establish an international reputation. In 1955 he published The Sane Society, which picked up themes introduced in Escape from Freedom, as it used the norm of the productive personality to critique capitalist conformity, consumerism and the erosion of democracy. The next year, Fromm came out with The Art of Loving, which sold in excess of 25 million copies, more in Germany than any volume other than the Bible.

Later in life, Fromm fearful of nuclear annihilation became an activist in the service of disarmament and international peace. His reputation enabled him to develop extensive correspondences with Adlai Stevenson, and later Eugene McCarthy, among others. And Friedman contends that Fromm influenced John Kennedy to develop a negotiating posture towards Khrushchev rather than ramp up what he saw as inevitable bellicosity leading to nuclear war.

Friedman’s treatment of Fromm is meticulously researched and balanced. His critique of Fromm confirms conclusions that I had drawn even in my admiring youth. Among them is that despite Fromm’s creativity, his influence rested greatly on the clarity and power of his prose, and much less so in the rigor of his scholarship. One is often left with the sense that authorities invoked by Fromm, whether they be Aristotle, Spinoza, Freud or Marx, are felicitously shaped to fit the Frommian mold. Despite, the remonstrations of serious academics, Luther is portrayed as the prototype of the authoritarian, Spinoza, the champion of humanistic psychology, and Marx the paragon of the happy and productive character type. This hagiography contradicts a virtual consensus that Marx, though a genius, was a miserable human being, plagued by poverty and boils, given to drunken brawls in his youth, and with two daughters, whom he undoubtedly loved, but who ended up committing suicide.

Another flaw in Fromm, unasserted by Friedman is Fromm’s implicit but unflagging moralism. In heralding the productive human being, as the ideal type, Fromm failed to acknowledge humanity in its fallen state, so to speak. One leaves Fromm beguiled by his humanistic vision, but deflated that one cannot reach the bar he has set impossibly high.

Friedman has produced the most detailed, comprehensive, balanced and readable biography of one of the twentieth century’s most influential thinkers. Yet his study would be more satisfying if he had clarified what it all adds up to. Oddly missing is Fromm’s place as a harbinger of the Humanistic Psychology Movement with figures such as Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, Albert Ellis and others who helped to shape the geist of the 1960s. But the author is to be commended not only for his rigor, but for a putting before us the life of thinker who so powerfully influenced his own time, if not, unfortunately, our own.

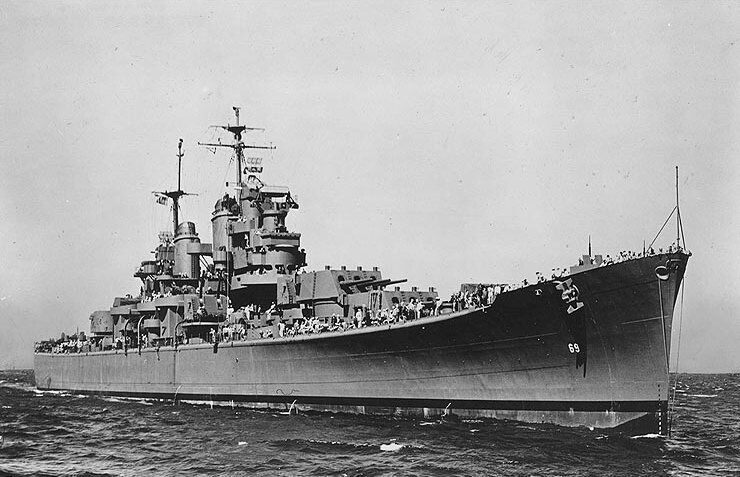

Time and Tide by Thomas Fleming

This novel of the Second World War in the South Pacific makes a fictional cruiser called the the Jefferson City the locus of most of the most important events of the war. There is a terrible scandal when the captain leaves a major battle, for which he is relieved of duty. Kamikazes disable the ship. The ship is chosen to carry the atomic bombs to their rendezvous with the planes that will drop them on Japan. Shortly after that is the grand finale of abandoning ship and floating with sharks and oil and not enough lifeboats for the hundreds of guys still alive.

Fleming writes the action and historical background very well. I learned a lot, never to be sneezed at. Fleming was an historian as well as a novelist. and this book does all the shipboard life and various levels of sailor's experiences very well. One other thing he does well is occasional chapters allied "Mail Call '' made up of fictional letters from characters back home. So I'm glad I read the book, but I frankly disliked about a third to a half of it. I was fascinated by the parts about keeping the boilers from exploding about decisions on the bridge, about the closed off claustrophobic spaces below decks, and how good captain maneuvers his cruiser.

But, oh dear, the events on shore! The main character is Art McKay, the replacement captain of the Jefferson City who is very good at maneuvering cruisers. But he is also in an unhappy marriage and searching with much angst for what really happened to his best friend, the previous captain of the Jefferson City. I wish he had skipped the women altogether. The navy wives love the navy more than they love their husbands. The various young women in ports of call just want to have sex with sailors. Everyone who has an inner life at all, male or female, has it revealed in wildly melodramatic if not operatic passages of narration.

I understand Fleming's ambition to write a really big epic novel of men at war. He wants to lift up the sacrifices of the sailors and officers, and to throw a bone to the ladies. I just wish he'd given up epic and written what he was good at. A much better Big American War Novel (albeit not about the war in the South Pacific) is one I reviewed in this newsletter a few years back, Irwin Shaw's The Young Lions.

If Time and Tide had stuck to what it does extremely well, it would have been a much slimmer, tighter, and less melodramatic book.

The Gods of Tango by Carolina De Robertis

This is mostly recommendation: an awfully good book. It goes from a village in Italy to Buenos Aires; from anarchist rebellions to the development of tango; from a girl who loves women and thinks there is no one else in the world like her to a permanent life as a cross dresser.

There are wonderful scenes of poor people in communal living situatioins and lots of suffering, especially by poor women in early 20th century Argentina and Uruguay. I also liked the rich scenes of several subcultures: music of course but also crime and the world of brothels.

Some of the story is predictable, or maybe not as smoothly prefigured as it might have been, but De Robertis's work is unfailingly interesting, engaging, vivid, and politically astute.

An Act of Remembrance & Other Mostly True Historical West Virginia Stories by Randy Safford, Reviewed by Danny Williams

British soldier Henry Church was captured during the Revolution, and held in a Pennsylvania P.O.W. camp. When the war ended and he was free to go home, he decided to stay in America instead. He got work on a local farm, married Hannah, the farmer’s daughter, and the couple moved to the unsettled hill country of what is now Wetzel County, West Virginia. There they lived out the remainder of their 83-year marriage. They both passed in 1860, at age 109 and 106. The settlement that grew around their farm is now the town of Hundred.

Sadly, that’s all we know. All the daily details of these two extraordinary lives are lost. In the short story “It Must Be the Water,” Randy Safford shares excerpts from a fictitious diary kept by Hannah Church. It’s a tale of hard work, faith, and family, told in an unmistakably human voice.

In An Act of Remembrance, Safford populates eleven West Virginia events with genuine flesh-and-blood characters. The various stories are heartwarming, maddening, tragic, whimsical, or haunting. Between the war and the presidency, George Washington explored some of his vast western land holdings, and recorded in his journal that he met with Frederick Ice, operator of the first ferry service across the Cheat River, near present-day Morgantown. In the aftermath of Senator McCarthy’s infamous red-baiting speech in Wheeling, an art professor at Fairmont State College was hounded out of town for refusing to join in the frenzy. A terse police report is all we know about Belle Lemon, one of the many naïve young farm women lured to her doom by the glitter of the city. A farmer and amateur chemist near Philippi discovered the secret of Egyptian mummification, but then came the thorny problem of just what to do with his two human subjects. An Act of Remembrance invites readers to experience history as it really happens—through the human experience of those who live it. Every story leaves the reader thinking “Yes, it might have happened just like that.” Even the one about the tomato.

Randy Safford is retired from a career as a psychiatric nurse. This is his first book-length publication, but he has obviously put a lot of time into the craft of writing.

Okay, yes, I edited this book, to the small extent it needed a second set of eyes. No doubt I made some suggestions on the word or sentence level, and no doubt Mr. Safford agreed with some and disagreed with others. I especially recommend this book to aspiring writers. It’s an encouraging reminder that the stuff of literature is all around us.

GENRE NOVELS

The Overlook and The Nine Dragons by Michael Connelly

The Overlook is a bit of a pot boiler-- short and spare. You feel Connelly either getting tired of the whole Harry Bosch product--or maybe, optimistically, gearing up for a fuller book. Still, Connelly's pot boilers give enough satisfaction to make them worthwhile. The plot here appears to be on the surface about a terrorist plot, so the FBI gets involved, and is put in its place by Bosch--as usual. The whole story takes place in twelve hours or so--except for flash backs to Vietnam and to the death of Bosch's mother. This one is for fans, and for people who like a barely-more-than-novella crime and mystery novel.

But The Nine Dragons is the complete package. I've read this one a few times. It starts with the murder of a Chinese immigrant liquor store owner in L.A. and ends up with Bosch in Hong Kong for 39 hours. This is the one with ex-wife Eleanor Wish and a serious threat to their daughter Maddie. Bosch ends up taking his daughter home with him, so it's big emotional moment. Mickey Heller appears. Bosch is humorously inept at fathering; extremely "ept" with detective work which he doesn't always do within police regulations. But we Americans love our outlaws.

This is one of the Bosch novels that keeps the characters consistent but pulls in ideas about parenting and who is guilty, and a lot of other good stuff.

All Systems Red and Artificial Condition by Martha Wells

All Systems Red is a science fiction novella in the voice of Murderbot, a part-organic security robot who has hacked its "governor" and officially gone rogue. Murderbot has an endearing sort of bright, on-the-spectrum voice. Ir really likes people but is terrified of being asked to describe its feelings. I got a $3.99 version from Kindle and wanted more, so I bought the next book for $10.99. Yes, you got me, Amazon–I'm an offical sponsor of Jeff Bezo's trips to heaven. The weird thing was that I would have bought a used paperback, but they were even more expensive than the Kindle download.

The second book, Artificial Condition sends Murderbot looking for its own origin story and how and why it disconnected its governor. Wells knows her robot-soldier-killer genre, and while there's lots of action, uses it for her own fun and values.

The Cloud Roads by Martha Wells

More Martha Wells. Fantasy, but pretty well-grounded with minimal magic, and as long as you accept how the various species have powers to fly, heal quickly, etc., it works very well. The Raksura, for example--who may in fact be two species combined, can shift from a "groundling" form to a more elaborate state that, in some cases, has large magnificent wings.

The main character Moon is a "solitary" who finds/is found by his people, the Raksura. This gives Wells all the potential mishaps and misunderstandings of a newbie to the culture. Moon turns out to be a valuable type of being called a consort, which is a potential mate to the Raksura's very active and powerful queens.

The voice of Moon and most of the other charcters is a generic teen/twenty something American smart ass that shows up in a lot of current Young Adult fiction, although I'm not convinced this novel is Young Adult.

I'll probably read at least one more book of this series.

The Color of Magic: Discworld by Terry Pratchett

This science fiction/fantasy comedy by Terry Pratchett is clever and funny. I laughed out loud a couple of times, usually at anachronistic wordplay and puns, but also at the wonderful ne'er do well characters, the failed wizard Rincewind and the tourist Twoflower. Twoflower just wants to see everything, and his magical travel chest follows along after him with large amounrs of money and a hundred little legs.

This is a lot of fun, even though it's the kind of fantasy where anything that might amuse goes, and only afterward does Pratchett, sometimes half-heartedly, give explanations.

RESPONSES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Marc Rapaport says, "I just finished reading The Anomaly. It is excellent ... a crisp, light read." Here's the New York Times review: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/23/books/anomaly-herve-le-tellier.htm.

Danny Williams says, "Last book that kept me up literally all night: The Red Tent, by Anita Diamant."

Bruce Kawin writes, "You know those people who don’t want you to read Beloved? They wouldn’t want you to read this either. Hilton Obenzinger’s Witness: 2017-2020 is a lyrical, precise, painful, and darkly amusing walkthrough the Trump years with a poet who here reminds me of Whitman."

The Atlantic has a list of 15 books from the past two decades that they think people should consider reading. The ones I am familiar with (The Known World, Never Let Me Go, The Round House) suggest that the others are probably good reads too.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Shirley Charles-Robinson's Hearts Cry: Made with Purpose for a Purpose has just been published. Colie Kreuger says, "By sharing her own life, she uses her experience and wisdom to usher us into a journey of growth, discovery and God's goodness." Sandy Lee Schaupp says, "I appreciate her openness with her own struggles as well as her personal background as a child of immigrant parents."

The book is available from Amazon among other places.

Suzanne Martinez has had a series of publications and prizes that everyone should check out. See her webpage here, and especially note the story "The Contract" from the Best Short Stories from The Saturday Evening Post Great American Fiction Contest 2022 Anthology. This one is about young artists struggling to make it before DUMBO was chic.

A bookstore/publisher called Monongahela Books specializes in American history & culture.

Victor Depta has a new book of poems, Eternity Is That, a collection of lyric poems which includes the four seasons as they relate to his experience of enlightenment. The natural world is expressive of eternity, as evidenced by that wild flower, that weed, that animal, that human being. Eternity Is That can be purchased through Blair Mountain Press and at amazon.com/books.

Marc Harshman writes: "Happy to announce the publication of this little pamphlet of two poems (Two Views of Oxford. Many thanks to B. J. Omanson, editor and publisher at Monongahela Books for this beautiful production."

Timothy Huguenin has won an Indie Author regional award-- See our review here.

Books coming into the Public Domain this year, according to Lit Hub include, among others:

Willa Cather, My Mortal Enemy

Agatha Christie, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

William Faulkner, Soldiers’ Pay

Sadegh Hedayat, The Blind Owl

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Ernest Hemingway, The Torrents of Spring

Georgette Heyer, These Old Shades

Zora Neale Hurston, Color Struck

D.H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent

D.H. Lawrence, The Rocking-Horse Winner

T.E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

A.A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh

Vladimir Nabokov, Mary

Dorothy Parker, Enough Rope

Franz Kafka, Das Schloss (The Castle)

Yasunari Kawabata, “The Dancing Girl of Izu”

Vita Sackville-West, The Land

GOOD READING ONLINE

Nechama Moring's piece in Talk Poverty on the high cost of intrauterine insemination for people who are poor and LGBQT.

Diane Simmons's essay "Principles! You're Making a Killing on Them!" was nominated for a Pushcart!

Terrific piece called "Cede the Day" by Shelley Ettinger at Gertrude Press --about days when you don't manage to get anything done and feel bad about it.

And if you haven't read it, don't forget her moving novel Vera's Will!

Latest bittersweet fiction by Lewis Brett Smiler. Read "The Debt" at Academy of the Heart and Mind.

Marc Rapaport recommends this short story about a spy and a Muslim family, and an interview of its author. He says, "I thought, wow, what a creative use of voice. The author's approach is a particularly effective way to convey his message. I felt the narrator's conflicted emotions (that's putting it mildly) about his complicity in the invasive surveillance of his own people."

Blog piece by Joe Chuman on having Cornel West as his mentor.

At Lit Hub by Colin Dickey writes about re-reading Mrs. Dalloway during the pandemic at Lit Hub.

Rachel King's substack piece on Westerners (she's from Oregon).

Another installment of Birgit Matzerath's blog: here she responds to hearing Jeremy Denk perform the Well-Tempered Clavier Book I at the 92nd Street Y in NYC. She is, herself a much-loved interpreter of Bach.

ESPECIALLY FOR WRITERS

Writing Workshop with Barbara Rosenblatt

Do you want to share important life experiences through your writing? Our stories are part of what makes us human. Whether you are a lifelong writer or a beginner, this class is for you. We will help you jump-start your memories, organize your ideas, and edit your work. Bring a notebook to each class and be ready to have fun! We use the book Writing the Memoir, by Judith Barrington

Where: Zoom

When: Eight Wednesdays, Jan. 26, 2022, through March 16, 2022

Time: 7:00 PM to 8:30 PM.

Cost: $90 Takoma Park residents, $100 Non-residents.

Registration begins Dec 22, 2021, at www.takomaparkmd.gov/recreation and click on the ActivNet logo halfway down the page on the left side.

Rachel King is writing an interesting Substack blog series on what is working and not working as she publicizes her new book.

LGBTQ literary contests from Lambda

Hot Sheet -- what's up in publishing. They offer two free issues, then you have to subscribe.

Some publishers open for submissions; a free newsletter for authors and more

Fish Publishing

Authorspublish Newsletter/

Shambhala Publications: Open for book submissions

Authorpods.com -- a site for getting authors for your books club and much more.

What does "indie" mean? Richard Babyak says on an Authors Guild Discussion Board:

... the word "indie," for independent, has different meanings for different contexts.

• An indie bookstore is a store that is not part of a large chain.

• An indie press is a smaller publisher not part of the big five.

• An indie author is a self-published author.

DEPARTMENT OF DANNY WILLIAMS

1. Look Up Everything

1) You'll catch some errors, and

2) it might take you somewhere interesting.

In a spy-adventure novel, a photo of Pee Wee Reese was displayed in a New York Yankees-themed bar. I saved the author from severe opprobrium, if not physical harm. In a very fine short-story collection, Billie Holiday was in federal prison. But in prison, she would have been Eleanora Fagan, and some reader would have caught this and been distracted from the story for an instant. Ironweed once tried to bloom in July. I didn't know what ironweed was, so I knew I needed to (all together now) Look It Up. For a lengthy historical romance, I looked up dozens, if not hundreds, of names, distances, dining conventions, minutiae of historical weaponry and horsemanship and medicine and religion. The author was nearly perfect, and now I have the pride of knowing more that the average guy about northern Italy in the 1520s.

In a manuscript long ago, an older lady was thinking back to her young days in the 1940s, and remembering the woman who taught her to use Tampax. So I needed to confirm that Tampax would have been right for the time. It was. So said the "Museum of Menstruation," which one Maryland man created, curated, and housed in his basement. The site is even more weird and wonderful--and educational--than you might imagine. I really want to know a lot more about the man who does this. How did he come to be this guy? Please, someone, complete his character and write him.

2. Danny at work: What a Book Editor Does:

A lot of times, people...ask me, “Danny, just how does it work when a writer brings you a manuscript?” Then I would answer, “Well, it depends on the writer, and on the manuscript.”

At times I have helped guide an early draft into a published book. I told the author of a short-story collection that one piece was not as good as the others. He agreed, and in two weeks came up with a sparkling replacement. One novelist was actually a pamphleteer in spirit, with an important message to share and that’s all. I had him list 20 facts about each main character—height, hair, hobbies, wardrobe, diet, etc.—and in a quick rewrite he breathed life into his people. For a well-written novel, I pointed out that two characters had similar-sounding names, and recommended “activating” some passive verbs. Everywhere, I look for strings of long sentences, clichés, needless tense shifts, overuse of what a more innocent age called the copular verb, and the thousand natural shocks the flesh is heir to. I submit every proposed edit to the author for approval or review, even spelling corrections. Sometime the writer agrees, sometimes not. Either way they have taken another look, which counts as a win for both of us.

The first two or three hours or so I “work” for free. Mostly it’s reading and thinking, which is what I do anyway. My feedback includes everything from my overall impression to some sample pages of what my work would actually look like. Then if the writer wants to continue, we talk about a range of time and money budgets. After we agree on a plan, we sign a contract and get busy.

I own my work, the same way my authors own theirs. We are both proud of what we do, and we both want to make the final product worthy of pride.

3. "Replace" as an Editing Tool

The “replace” function can be a powerful tool for fine-tuning a text. There are a couple of ways I like to use it, and if I am in early enough on a manuscript and the author is open to my input, I often recommend they do it themselves. (When I am fortunate enough to have work at all (wink-wink).)

First, “replace” can identify clusters of is/are/am/been/was/were verbs. Nothing wrong with any of these words, but probably you want to be aware if they are massing anywhere. Rewriting with a stronger verb can often improve a sentence. Plus, every passive sentence contains one of these words, and probably you don’t want to dwell too long in passive-voice land. (Yes, passive sentences are necessary. They are especially useful if you or your character want to avoid stating the sentence’s subject. Richard Nixon: “Mistakes were made.”)

So here’s how. Replace each of these words with boldface. (I like to go a chapter at a time.) Now you can spot densely-populated regions by just swimming your eyes over the pages. I wish I had thought of this 40 years ago. The first paragraph of the liner notes for that Glenville recording still haunts me.

One of my weaknesses as a writer is an occasional over-fondness for long sentences. To identify passages where I’m channeling my inner Faulkner, I replace every period with a paragraph symbol. Since I’m already adding space after each paragraph, this makes every sentence clearly announce its girth. Even though I feel like every one of my tumescent constructions is a thing of beauty, I shed not a tear as I bust up clusters of them.

I also like to temporarily embolden “very,” and any other throw-away words I suspect may be lurking.

Email me (editorwv@hotmail.com) if you have any comments on this or anything else. I have an opinion on nearly every topic. And tell me what you’re working on. Don’t send a sample, just a few words about your baby. I’ll reply with an encouraging sentiment or two.

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 220

March 7, 2022

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online! Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

Sister Souljah, Margaret Atwood on a stamp, Jill Lepore

SPECIAL EDITING OFFER FROM DANNY WILLILAMS!!

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue # 220

Reviews are alphabetical by author. If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW

Book Reviews

Notices of New Books & Announcements!

Read/Watch/Listen Online

Recommendations and Reader Responses

Especially for Writers

Shameless Commerce

Books of General Interest

Genre Selections

Irene Weinberger Books

Book Reviews

Jackson v. Witchy Wanda: Making Kid Soup by Belinda Anderson Reviewed by Eli Asbury

The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood

The Drop & The Black Box by Michael Connelly

Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other), Mark C. Carnes, editor

One More Day by Diane Chiddister Reviewed by Ed Davis

These Truths by Jill Lepore

Bluebird, Bluebird by Attica Locke

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

A Glass of Blessings by Barbara Pym

The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah

Hate: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship by Nadine Strossen reviewed by Joe Chuman

Book Reviews Issue 220

BOOKS OF GENERAL INTEREST

Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other), Mark C. Carnes, editor

I finished an enjoyable if desultory two year project of reading historical novels suggested by Mark C. Carnes's Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other)

. Professor Carnes's historians and novelists seemed to enjoy the project: one writer,Thomas Fleming, is both novelist and historian.

Of course there is plenty of cheerful disagreement. John Updike said, "Insofar as history lives in the telling, and persuades us we are there, it is a species of fiction." (p. 60). Russell Banks, on the other hand, wants a wall between history and fiction. He writes, "[Fiction] is strictly its own self, a cluster of images obtained solely from words structured and organized in such a way as to produce a clarifying dramatized vision of the truly human. At least, that is the fiction writer's hope. For while histories and biographies must have subjects and are unreadable if they don't, a story or novel has no subject outside itself. If it does it is likely to be a badly written story or novel." ( 69). Banks is pretty much going full New Criticism here, and New Criticism is, of course, nearly a century old. Personally,I think fiction does a lot more than that. But then, I write fiction.

Over all, I like the novelists' novels better than their essays. The historians' essays, on the other hand, tended to be extremely respectful of the so-called creative works, and sometimes even a tad envious They came across as generally good readers and open-minded

I didn't read all of the novels. I had already read several, and I reread some of those as well as filling in gaps in my reading. It was a pleasure to revist Gore Vidal's Burrand Barbara Kingsolver's Poisonwood Bible. (I'm putting links in this review to my remarks elsewhere on the books). The Vidal and Kingsolver are wonderful books, and I also liked a lot (but didn't reread) Don DeLillo's Libra, a fictionalized account of Lee Harvey Oswald's life. Nor did I reread Russell Banks's formidable Cloudsplitter about John Brown. Russell Banks always feels too heavily portentous to me. Here's a link to my thoughts on Cloudsplitter a few years back.

The reading list itself is worth the price of admission (in my case, free, as the book was in a small town library give-away pile). I'd been meaning for a long time to read somethig by Wallace Stegner, and Angle of Repose was a good place to start. Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain was on my list too, and another old favorite of mine, along with Burr and Kingsolver, was Larry McMurty's Lonesome Dove. New to me, and very good, were Madison Smartt Bell's Touissant L'Overture novels.

My least favorite was Thomas Fleming's Time and Tide. He said in his historian essay some sensible things about the experience of being both a popular historian and a popular novelist, so the essays are okay, especially when he talks about the history he based his novel on. And the novel was quite good on shipboard life (Second World War in the South Pacific) and battle, but not so much on the human beings he laboriously creates. Some of the men characters were passable, but the women all seemed to be cut-out illustrations from some nineteen-fifties women's magazine. See my full grumpy remarks here.

So while I recommend and apprreciate the collection as a whole, I do feel the need to say it is short on women writers and writers of color. Yes, yes, yes, I know it was published twenty years ago with the pool of books available then, and yes, it has Kingsolver, Smiley, and Dillard and of course Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, but that's out of twenty or so novels. And Professor Carnes teaches at one of my alma maters, Barnard College!

What I'd really like would be for him to do another volume--how about Morrison's Beloved or Julie Otsuka's The Buddha in the Attic? Or Harriet Arnow'sThe Dollmaker? Or James Welch's Fools Crow?

Send suggestions! I'm happy to share.

These Truths by Jill Lepore

... which Joe Chuman reviewed in this newsletter (#217) a couple of months ago. His review is a lot more thorough than mine, which is mostly just to say I read it and am glad. It perfectly easy reading, except in the sense that it is dense with ideas, perhaps more than facts–Lepore goes very easy on numbers and dates. So I enthusiastically add my recommendation to Dr. Chuman's.

My only caveat is that I found her recent history, especially her take on presidents, less compelling than the early parts. She tries to be critical of Democrats as well as Republicans, and Lord knows they deserve criticism, but personally, for the last twenty years or so, I've been inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt because of the

appalling alternative.

One of her best themes in the final third or quarter of the book is that it is nothing new that the Republican Party has been acting above all to get into power and serve the interests of the rich for many, many years. She points out the explosion of Republican interest in "rights," especially unborn rights and gun rights, has been used cynically to get votes

She has a nice trick of bringing to the fore not necessarily people who were never famous, but people we don't talk about a lot: David Walker a black abolitionist in the early nineteenth century and Maria Stewart in the later nineteenth century, who was the first black woman to write a manifesto. These people and many others were accomplished and interesting, and new to me.

She also makes an interesting case for the often-forgotten anti-Feminist Phyllis Schlafly as a chief engineer of the divisions in the USA today.

Lepore also details the development of civil rights, which (white) Americans tend to view as something that exploded full-grown out of Martin Luther King Jr.'s forehead around 1960. In fact, The strategies brought to fruition in the early nineteen sixties in the movement around King had already been used extensively in the nineteen forties during the second world war.

She also writes extensively about how the Confederacy was rooted clearly and openly in white supremacy, and how the anti-communist right wing in the twentieth century mixed sexuality and politics in an amazingly brutal way to attack people on the left (and keep them in check--like the great Bayard Rustin). Also excellent and surprising to me are her sections on how Hoover failed and FDR succeeded in using radio for political power. She links Orson Welles's famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast to Hitler's invasions in 1938. Everything about radio is fascinating, and gives our current Internet and social media context.

And I can't leave out one of my favorite fun facts: the Republican party and the Right Wing had long supported family planning, and Barry Goldwater and his wife were once on the Board of Directors of the Phoenix, AZ Planned Parenthood.

I'll return to this book as a resource often.

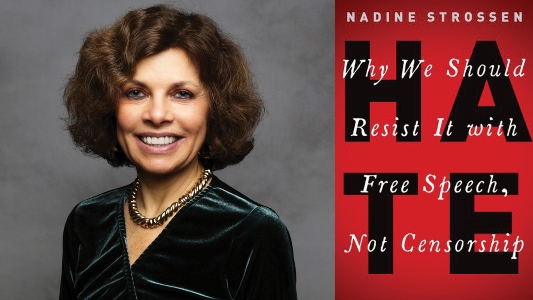

Hate: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship By Nadine Strossen reviewed by Joe Chuman

Nadine Strossen, the former president of the national American Civil Liberties Union, has written a book on hate speech as important as it is timely. In the midst of our current turbulent climate resurgent with hate groups and militias brandishing the mantras of white supremacy, writing this book is also an act of courage. The espousing of "hate speech” directed at minorities, immigrants, political adversaries, and others may tempt some to want to see laws that enacted that are intended to prohibit and rein it in, but Strossen's book presents a series of detailed and compelling arguments as to why we should not succumb to that temptation.

It was my privilege to recently interview Professor Strossen on Hate: Why We Should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship as one in an ongoing series of discussions with noted authors under the aegis of the Puffin Cultural Forum in Teaneck, New Jersey. Strossen, who is a professor at New York Law School, is a sharply articulate and deeply informed defender of the First Amendment. Her book is tightly argued, going beyond legal issues to embrace relevant social science, psychology, and judicial history. As a student of human rights, I found it of great interest that Professor Strossen ventures outside the American context to reference the international human rights regime as well as the fate of hate speech laws in foreign countries.

It is evident that Strossen's thesis is not a defense of hate speech but of the right to hate speech, and she reminded me early in our interview that the only verb in the book's title is “resist.” As she makes amply clear in her text, the allowance of hate speech is ironically one of the strategies that is necessary in the struggle to resist it.

A major share of her argument is that the laws to preemptively prohibit the utterance of hate, whether targeted at individuals or groups, have no place in a free and democratic society, but actually exacerbate the very conditions they are intended to suppress.

The prevailing principle, long championed by the ACLU, is that under the First Amendment, the government must remain neutral with regard to the content of speech. It is simply not the government's role to dictate what you or I may express in speech or writing. But the right to free speech is not absolute, and a strength of Strossen's presentation is that it is richly detailed and nuanced in elucidating the complexities of hate speech laws, their consequences, and ways to counteract hate.

Strossen makes eminently clear that speech is by no means otiose nor powerless. Words inform values and attitudes, and they can and do motivate action for good and ill. Some hate speech in fact is prohibited and the Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter with regard to setting boundaries for which speech, in narrow circumstances, is justifiably unlawful. These boundaries have changed over time. She notes such a change: “Until the second half of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court enforced the deferential 'bad tendency' standard to permit government to suppress speech whenever it maintained that the speech might cause harm at some future point.” For example, as a result of decisions rendered in 1919, the Court upheld criminal convictions for speech opposing American involvement in World War I, on the grounds that it might encourage draft resistance, and the conviction of Socialist Party leader, Eugene V. Debs was upheld for giving a wartime speech opposing the draft. But this standard subsequently changed primarily through decisions of Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis, who confirmed government neutrality, expounding that the First Amendment bars the government from suppressing “opinions we loathe.” It is this standard that we retain and which Strossen strenuously defends.

Among the narrow circumstances in which hate speech remains prohibited is “the emergency principle.” These circumstances are all context-specific. Examples include speech involving “true threats” in which the speaker seriously intends to commit an unlawful act of violence against an individual or a group and the object of that speech has a reasonable fear that the assault will occur. Context, again, is crucial. So if a coven of KKK members burns a cross unseen by others, this expression does not meet the emergency test prohibition. But burning a cross on the lawn of an African-American assuredly would and is illegal. Speech that intentionally incites imminent violence, or ensures that violence is likely to occur is also barred. Moreover, harassment is not protected, including persistent harassment in the workplace that creates an abusive work environment. On the other hand, generalized threatening words construed to be politically hyperbolic or rhetorical, are legally permissible.

However, with obvious pride in what she sees as the common sense of the American tradition, she underscores the broad scope of free speech. To make the point, Strossen frequently states that the emergency test does not bar speech that is “disturbing, disfavored, and feared,” the last implying that the message might indeed contribute to potentially harmful conduct at some future time. But, again, fear of potential harm is not sufficient to outlaw such speech.

The reality that some speech is felt as disturbing is especially relevant because it touches upon an often encountered source of conflict that has become increasingly familiar. Both Nadine Strossen, who is a professor of law at New York Law School, and the current reviewer, who teaches human rights in the academy, are aware of how fraught speech has become on college campuses. The classroom, which should be the premier venue for the debate of ideas, including ideas that are controversial, has often been turned into an arena wherein previously engaged and lively discussion now suffers a chilling effect. We see the introduction of hate speech codes on campus. But beyond such codes censorship extends further. She notes,

“In at least some circumstances current campus censorship threatens even more speech than the invalidated hate speech codes of the past. For example, some institutions have gone so far as to prohibit ideas that some students may find “unwelcome” or make them “uncomfortable.” “...today's capacious concept of hate speech is often understood as encompassing the expression of any idea that some students find objectionable.”

“Even beyond official suppression, many public colleges and universities have experienced self-censorship among students and faculty about sensitive, controverted topics that urgently call for candid, vigorous debate and discussion. Given the adverse consequences at stake, there is widespread fear of being accused of 'hate speech,' or even saying something that makes someone 'uncomfortable,' which is a damning indictment in the current campus climate.”

No doubt much of the discomfort relates to discussion around race and gender, and many professors sense that walking into the classroom today places them in a fraught environment. It is at this point that Strossen moves from law to social science to defend the notion that the damage done by disquieting speech is often misplaced.

She does not deny that hate speech sometimes does contribute to psychic and emotional harm’ to some people it disparages. Arguments are made that because of structural power inequities with deep historical reach, institutional racism being the most salient, such harm is palpable and offensive speech should be curtailed. But these circumstances entail a great deal of nuance and variation. Moreover, she asserts that more empirical research needs to be done on the real effects of disturbing speech on campus. Clearly, she believes that the negative harms have been overstated. Invoking social scientists, she notes,

“...experts recognize that 'there are wide individual differences regarding what constitutes a ‘hateful message,' and that 'what speech is considered harmful depends critically on situational variables,' including bystanders' reactions, the message's perceived intent, the relationship between the speaker and the listener, the topic of discussion, the location of the conversation, the language used, the speaker's and listener's body language, and the tone of voice.'” Studies she invokes indicate that different listeners had different responses to hate speech. In response to disturbing speech on campuses and elsewhere, her thesis counsels a broad range of responses from shoring up personal resilience to relevant education and to what she refers to as “counterspeech.”

When it comes to racist speech, Strossen invokes a significant number of Black leaders including - Thurgood Marshall, John Lewis, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Eleanor Holmes Norton, and the NAACP - as opposing hate speech laws, recognizing that access to free speech has been among the most potent tools in the struggle for social justice and minority rights.

This provides a good point to segue into a central argument that hate speech laws, though initially emotionally satisfying, in application fail to curtail the very hatred they are intended to suppress and in some instances actually amplify a hateful environment. Moreover, such laws not infrequently target the very disenfranchised groups they are meant to protect. In short, hate speech laws are dysfunctional.

Nadine Strossen draws amply from the international context, especially from Europe and Canada, to illustrate the problematic consequences of such laws. A central problem is that hate speech laws are notoriously vague and therefore impossible to apply. She notes the Canadian Supreme Court's efforts at interpreting hatred in laws that punish speech 'that is likely to expose' people to 'hatred or contempt:' 'unusually strong and deep-felt emotions of detestation, calumny and vilification' and 'enmity and extreme ill-will...which goes beyond mere disdain or dislike.' To make her point, Stroessen asks “If you were a juror, would you be able to distinguish between speech that conveys 'disdain,' which is not punishable and speech that conveys, 'detestation' or vilification,' which is?”

In the American context, she cites an incident in which students at Harvard hung a Confederate flag from their dormitory windows, in obvious defiance of campus hate speech codes. In response to the Confederate flag and to expose its racism, other students hung swastikas from their windows. She asks, “should the swastikas count as “hate speech” or as anti-”hate speech?” She concludes, “...'hate speech' is irreducibly riddled with ambiguity, conflicts and confusion.” “...I have done my best to track down and read every 'hate speech' law that has been enacted or proposed, and have yet to encounter one that avoids the serious flaws that I have identified.”

A further argument in opposition to hate speech laws are that they can ricochet to target the very vulnerable groups they are meant to protect. Black Lives Matters has been attacked as fomenting hate speech and if such laws existed there would be efforts at silencing the movement. In the current political climate such concerns are by no means remote. The counter-productive nature of hate speech laws was noted by columnist Glenn Greenwald when he wrote, “ Nothing strengthens hate groups more than censoring them, as it turns them into free speech martyrs, feeds their sense of grievance and forces them to seek out more destructive means of activism...Conversely as the aftermath of Charlottesville has proved, nothing exposes the evil of such groups, and this weakens them, like letting them show their true nature.”

A more extensive review would require a probing critique of the role of the internet and social media and their relations to promoting information that either sustains free speech and democracy or undermines them. The First Amendment, of course, pertains solely to government and public entities. Social media platforms are private enterprises and at this point are free to regulate speech however they choose. But it is Strossen's view and that of many others, though not bound by the free speech mandates of the First Amendment, social media, like colleges and universities, they should abide by its norms.

The extraordinary power and scope as such entities as Facebook and Twitter and other social media as conduits of information would ostensibly render that conclusion apposite. Strossen sees similar problems in banning hate speech on social media as she does with government, and she seems to be opposed to regulation.

While this debate goes beyond my personal expertise, my sense is that the issue requires a great deal of continued research and public debate. Social media, which initially presented itself as an unquestioned boon to the expansion of the marketplace of ideas, has arguably been transformed into a far more complex and conflicted reality. Professor Strossen points to the extraordinary capacity of social media to bring people together to organize for progressive social change. This is no doubt true. But critics point likewise to their appeal to impulse and often negative emotions in relentless pursuit of profits, their capacity to algorithmically feed back to people what they want to hear and thus reconfirm their biases, as well as their ability to silo hatred. Whether these gargantuan technologies enhance democracy or undermine it is not compellingly clear and I believe still an open question.

But what is clear to my mind, and as Nadine Strossen so compellingly demonstrates, is that when it comes to censoring hate speech the cure is far worse than the disease. In place of hate speech laws, she advocates counterspeech, which can take many forms. Among these approaches is speech that aims to refute hateful ideas, broader, pro-active education initiatives, and programs to empower disparaged peoples. Such approaches go beyond speech alone, but require programs to bring people together and to nurture values that will create a more inclusive society.

In my personal engagement with Nadine Strossen I encountered a scholar and activist, who is not only deeply informed on the fundamentals of freedom, but in our challenging times remains optimistic as to how far we have progressed, implying that a more benign future lies ahead. I found our encounter a source of needed inspiration. Readers will find Hate: Why We Should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship a powerful and necessary defense of a cornerstone of our democracy and how to keep it.

The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood

I decided to read this after seeing an article in The Atlantic called "Fifteen books You Won't Regret Rereading"

-- and presumably reading for the first time as well. I have never been partiularly drawn to Atwoodt--I respect her work more than love it. But her strength is demonstrated to me by how this novel grew slowly on me.I started by highlighting some passages of her splendid language, and enjoying the eccentric childhood the creatrs for her two main-character sisters in their declining family mansion. I liked their caretaker Reenie. Sister-in-law Winifed is good too, wearing green alligator pumps and too much orange lipstick. The town, Port Ticonderoga, regularly mistaken by tourists for Fort Ticonderoga, is fictional, but Toronto is real, as are a number of events including a 1934 Communist rally. Everything about Ontario, actually fascinates me.

There is a novel-within-the-novel, never an easy sell with me. a book called The Blind Assassin which carries younger sister Laura's name. History is woven into everything, but elder sister and narrator, Iris, purports not to be very interested, even though se reports (well) on wars, labor difficulties, her awful (and rather flat) husband Richard who is an industrialist and opportunist.

It 's a big book that ties up all the loose threads and the end. Questions are answered: who really loved whom, who wrote what, who fathered Iris and Laura's babies. It's also good on old age as experienced by Iris. The result is an oddly quiet satisfaction, in spite of plenty of action and local color..

One More Day by Diane Chiddister Reviewed by Ed Davis

Diane Chiddister’s first novel One More Day (Boyle and Dalton, 2021), set at Grace Woods Care Center, an American assisted living center, is a joyful celebration of life. This is a great read for anyone wanting to understand aging in this era of increasing life span as well as increasing health challenges. Chiddister penetrates deeply the lives of both residents and their devoted caretakers: Lillian in her hallucinatory world of dementia; executive director Beth, pressured by new for-profit owners to change her gentle stewardship; Thomas, the former anthropology professor, alienated but ever curious; and resident aide Sally, who devotes her life to her patients and develops an especially close, touching relationship with Thomas.

Sally and Beth have little life outside their jobs, which, as Chiddister demonstrates, is both good and bad. Sally’s worked at Grace for 25 years, beginning in high school; Beth, in her sixties, has done this work all her life, at the cost of her marriage and any children she might’ve had. Sally has the uncanny ability to always do the right thing--apply a warm cloth, kiss a forehead, read aloud, wash the body of a patient moments after death as carefully and lovingly as she’d clean a newborn; she is the angel we’ll all want at our bedside when our time comes. Similarly, Beth’s commitment is 100%, and her values include knowing every patient’s name, interacting with each daily and keeping doors unlocked during the day, a decision that will come back to bite her but one that shows her total respect for the aged who are not to feel imprisoned.

Lillian and Thomas, the two residents we get to know deeply, are not stereotypes but real, living human beings. Through Lillian, the reader learns what it might be like to have dementia by experiencing it from the inside. It’s “fizzy” with heat and “big winds”--and flocks of birds that constantly and confusingly intrude, reducing speech to “Hello!” and “Yes!” Still, she has a rich inner life all too easily missed by the young and healthy. All Lillian wants is to return to the colonial brick home she shared with her husband and daughter, but when she tries to say home, it comes out “hmmmm.” Eventually, Beth and Sally figure it out; heartbreakingly, they can do nothing about it, until Lillian takes matters into her own hands--and feet.

New patient Thomas, long-retired anthropologist, is an astute observer, alternately critical and forgiving, angry and patient, cheerful and despairing. Sally touchingly cares for him like the father she never had--until his real daughter the former prosecutor arrives, creating plenty of sparks and opportunities for growth, even as death approaches. Breathtakingly beautiful passages in which Thomas relives the crucial experiences of his life as he lies dying will stay with me forever.

As for the caretakers, Sally the angelic aide is, for me, the book’s moral center. Loving and talented as she is at her work, she must come to grips with having sacrificed herself to a profession that will gladly take all you will give. In the course of events, she will come face to face in the workplace with the demons making her such a sacrificial lamb. Her relationship with a much younger male colleague provides drama, suspense and humor. Despite the novel’s focus on such serious themes, it’s also very funny; for example, there’s never anything but weather reports on the center’s TV, mostly hurricanes and tornadoes! Still, most residents stay glued to the set.

Most importantly--and movingly--Chiddister’s novel portrays older people as they really are, as diverse individuals. And, though without illusions, the book is amazingly uplifting and wonderfully written with gentle humor and subtle insight. It’s a must-read, an enjoyable read, for young and old.

A Glass of Blessings by Barbara Pym

I finished Glass of Blessings by Barbara Pym delightfully surprised. It is a lovely little world, precise and very foreign to me. Everything centers around the tea table and parish house and the determination by most everyone to do things properly. What happens is funny and small–the young married narrator Wilmet falls in love with a n'er do well, who turns out to be living happily with a younger man, slightly lower class, but she finds herself liking his young man, and even liking her husband by the end. There are more flirtations, no on-stage sex, and a lot of high church Anglican political stuff (a mini-Barcester Towers).

I was especially engaged with the various minor characters–but also with frivolous, flirtatious Wilmet herself. She's a true kept woman-wife who spends her time shopping and lunching. Allowing her to improve just a little is a major coup on Pym's part.

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

This is a brilliant and very funny and disturbing short novel that takes the fact of wild voraciousness of human infants and the contradictions of motherhood to entertaining, shocking, and beautifully phrased extremes. I was recalled to my early days of motherhood when I was struck by the animality of the selfish, voracious baby, and also how passionately attached to it I was.

What holds you to Chouette isn't the plot, although, of course, you do want very much to know how Oshetsky is going to end a novel about mothering an owl-baby. Several reviews called it a fable, probably because it has main-character animals and a maybe a moral. Not sure about the moral. A friend of mine who doesn't care for most fantasy, calls it a magnificent extended metaphor. I was impressed with it too, but glad it was a short book. It was so intense,and I read it so fast, loving being in it--and loving getting out safely.

Up until the very end, every sentence, every phrase, is a surprise. But maybe in the end the language is more surprising than the story. The set up is brilliant--a cellist who sort of falls into her marriage and tries to be a good little wife--her name or nickname is Tiny. She gets pregnant, and we gradually get hints of a strange real, fantasy, or dream past. She once lived in the dark "Gloaming," a kind of enchanted but also natural forest where she lived with a nurturing older Bird Woman and a sister-like owl companion.

You know violence has to come, that someone is going to die. Tiny narrates in first person, so by the unwritten contract of reading, you assume she will be alive at the end. Chouette the wild owl-baby might die; or Chouette might escape and some of the unlikable human beings die.

There is a false ending, and then the writer chooses a different one. The ending is managed well, and it makes me want to spend time with owls.

For more views on this book see Publisher's Weekly; The New York Times; and The Guardian. There is also an interesting blog-style piece online about Oshetsky's real height (not tiny), and her relationship with her real daughter.

GENRE NOVELS

The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah

This was recommended as a classic of "street literature" in a blog post at VICE.com by Kristen Corry (a senior staff writer at VICE).

Published in 1999, it is vividly written with pungent language and a feisty young adult narrator named Winter. Winter is a kind of teen princess, whose father is a drug lord, and who is trained to be a leader--and a high quality consumer. The tone alternates among hilarious, irritating, and heart-breaking.

Her mother, who shows her what to demand of your man, had Winter whenshe was 14. Both parents have taught her and her sisters to judge the world on very specific clothing labels, models of cars, and, especially, choices of sneakers. Fresh shoes, as in a new pair every week, is de rigueur. Winter tells us she is the queen of Brooklyn, but things begin to fall apart for her when her father moves the family to an enormous house on Long Island. He sees it as a move up and as safety for his family, but instead, there is a crash, and Winter is forced to use her brains and sex for survival while her dad is in prison and her mother is deteriorating and drugging back in the projects in Brooklyn.

One reviewer rather prissily spoke about her being a nymphomaniac. This seemed totally wrong to me: she's a teen-ager, and she certainly has sex and seems to like sex. She has a very teen crush on a man named Midnight who keeps her at arms' length, but much of the sex seems performative to me--consumed and traded. It's not that she has no libido, but rather that sex is something valuable to give and receive, like clothes.

On the run, Winter spends time in a group home for girls, then in a lovely Harlem brownstone owned by an African-American woman doctor, and shared with a young woman named Sister Souljah who gives inspirational speeches around the country and is friends with major rap stars. I'm not sure I get this--except as a widening of possibilities that Winter pretty thoroughly rejects. Her big project is to snag the rap star for herself. She sees no reason why she should have anything but the best. She attempts to get the star's attention, and ends up tricked by some of his entourage.

She finds herself broke, but is saved by an admiring and highly controlling drug dealer named Bullet who eventually leaves her in a car with some animals stuffed with cocaine. She is arrested for a crime she didn't commit.

Winter is scheming. completely selfish, with absurdly bad values and an adolescent optimism that makes her attractive in spite of all the rest. She is true to herself, even as she ends up in prison for 15 years with a big scar on her face. She will be 33 when she gets out, but a lot of her Brooklyn girl friends are in jail with her, so she is still the leader of an un-fashionable but powerful peer group.

The book ends with her first trip out in five years--under guard, to her mother's funeral, where she sees her dad, her flashy sister Porsche (who she decides not to warn about her life's mistaken direction), and her two little sisters in custody of her first love, Midnight, who has gone straight.

Winter is still surviving, still guardedly optimistic, the leader of her little world.

For some other views, see Publishers' Weekly and Kirkus Reviews.

The Drop & The Black Box by Michael Connelly

The Drop, with two cases going simultaneously, is mostly procedural, until a vicious "monster" serial killer is chased down. I don't think Bosch even gets shot at. His relationships to teenage daughter, present partner and former partner as well as to his nemesis ex police Irvin Irving are expanded and full of interest.

The Black Box was published next, in 2012, with Bosch finally beginning to use technology at least a little, but always needing someone younger for the serious searches. This one begins with a murder of a Danish journalist during the LA riots of 1992 and fast forwards to an Open Unsolved case. This is a typical, competent Connelly/Bosch story, and Connelly working on three cylinders if always more of a power house than lesser writers working on four.

Bosch figures out the killer with leg work and interviews and research by his partner Chu, lots of interactions with daughter Maddie, which are well-done, then a physically at-risk finale with a group of ex-soldiers and one very bad stone cold leader of the pack.

The minor characters (except Maddie) are not given a lot of detail, although there are a couple of interesting cop and gangbanger characters. But it isn't character development that interests Connelly here: just the thrill of the chase and Bosch himself, including his limitations, his determination, and his intensity.

Bluebird, Bluebird by Attica Locke

Good reading,and a funny contrast with with Chouette, which I'd just finished. The main character is Darren Matthews, a (rare) Black Texas Ranger with a marriage on the rocks and drinking too much. He's essentially a good hearted boy scout who is easy to like and root for, but he seems to me (am I being too picky? Showing my age and attachment to old fashioned gender roles?) a little lacking in the illusion of being a man.

That is to say, a female writer seems to be failing to create the full sense of a testosterone powered character. On the other hand, the East Texas setting (and the food) is terrific, especially the sense of wonderfully knotty and complex ties of hate, guilt, and blood among black and white people. There are some satisfyingly awful white supremacists, Geneva's diner and the folks black and white who show up there. The mystery is pretty interesting too.

Attica Locke is one of those vastly talented writers who takes on serious subjects and is always worth reading. Sometimes, though, she appears to have forgone the final revision.

I'm not complaining much, though, because I really did enjoy it.

CHILDREN'S BOOKS

Jackson v. Witchy Wanda: Making Kid Soup by Belinda Anderson Reviewed by Eli Asbury