Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 225

January 31, 2023

This Newsletter Looks Best. and its links work better, in its Permanent Location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

For functioning links and best appearance,

go to our permanent location.

Comments from Readers

Recommendations from Readers

The 1619 Project for Children

More for Kids

Kage Baker Discussed by Molly Gilman

Troy Hill on Isaac Babel

Shelley Ettinger's Best Reads 2022

More Hints from a Professional Editor by Danny Williams

Links to articles on AI and Cultural Appropriation

Three More by Michael Connelly

Announcements

Lists

Reviews in this Issue

Read/Watch/Listen Online

Just for Writers

How to Help Authors

REVIEWS

This list is alphabetical by book author (not reviewer)

We Are Not One: A History of America's Fight Over Israel

by Eric Alterman Reviewed by Joe ChumanThe Works of Kage Baker discussed by Molly Gilman

The Awakening by Kate Chopin

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly

The Last Coyote by Michael Connelly

Trunk Music by Michael Connelly

The Princess Bride by William Goldman

Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy

The Well-Beloved by Thomas Hardy

Chain of Evidence By Cora Harrison

A Shocking Assassination by Cora Harrison

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy

A Clash of Kings by George R.R. Martin

Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers

Agostino by Alberto Moravia

In the Lonely Backwater by Valerie Nieman

Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout

I Am Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout

A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews

Lincoln at Gettysburg: the Words That Remade America by Garry Wills

A couple of years ago I had a solid year-long project of reading books discussed in Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America's Past (and Each Other) edited by Mark C. Carnes. It was an interesting guide to American novels chosen and discussed by historians (Gore Vidal's Burr, for example, was one of them). It led me to some books and writers I'd always wanted to sample and some I'd never have come to on my own. I've been looking for a while for something comparable, and I just came across a new book, Kenneth C. Davis's Great Short Books: A Year of Reading―Briefly. It describes systematically with samples 58 short books, mostly fiction, arranged alphabetically. It doesn't have as much scholarly interest as the Carnes book--Davis insists he is just another Common Reader, and he seems determined to convince us all that reading is easy. His list is interesting, though, and by the time I'd finished three chapters, I'd stopped and read Alberto Moravia's Agostino, Carson McCullers' Ballad of the Sad Café, and Kate Chopin's Awakening.

As always, I welcome your suggestions, responses and enthusiasms.

ANNOUNCEMENTS WINTER 2023

Now available from the Jesse Stuart Foundation: Edwina Pendarvis's book about ballet in Appalachia, Another World: Ballet Lessons from Appalachia.

"Stepping Through History: Pittsburghers Reflect on City's Steps" is available on Paola Corso's blog. For more and her work see Paola Corso.com.

Valerie Nieman's novel In the Lonely Backwarter (see our take below) has won the 2022 Sir Walter Raleigh Award. The SWR award honors the best book of fiction by a North Carolina writer. Previous winneers include Reynolds Price, Jason Mott, Lee Smith. P, Charles Frazier, John Ehle, Fred Chappell, and Allen Gurganus.

Shelley Ettinger's story collection John & Yoko & Rowena & Me made the shortlist for the Dzanc Books prize.

Spuyten Duyvil has new books! Weird Girls by Caroline Hagood; Cirrus Stratus by Shome Dasgupta; It's No Puzzle by Cris Mazza, and much much more!

Excellent story by John Loonam now available on the Summerset Review

Lewis Brett Smiler's story "Down the Stairs" is on Creepy Podcast . The podcast is an hour, but his story only takes about 34 minutes.

MSW reviews "Foote" A Mystery Novel," by Tom Bredehoft at Southern Literary Review, November 2, 2022.

Norman Danzig's story "The Angel of Death" has just been published at Blue Lake Review.

Kelly Watt's short piece "Next Exit" is up for an honor!

Troy Hill has new stories online: The Write Launch published his long short story "Aquarium Life" and The Bangalore Review published his story "Ford Man.

REVIEWS

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

This is a really good book, and I recommend it with all my cylinders engaged. Probably her best work since The Poisonwood Bible, and maybe better.

I want to start, however, with a few caveats about things that some people may find problematic about Kingsolver's novels. First, most of her books, are weaker in the second half than in the first half. This is hardly uncommon: the longer the novel, the harder it seems to be to sustain momentum, and the easier to get lost in the trees. In Demon Copperhead, however, Kingsolver mostly stays strong. She is following a powerful structure (Dickens' novel David Copperfield) that carries this novel through the doldrums.

The second thing about Kingsolver is that while she is one of our best living novelists, she isn't subtle. Some admirers of literature may find this a problem, but Kingsolver has things to say, and she says them in your face. This can tend toward didacticism, and there is a little of that in certain speeches here, particularly things reported by Demon that his favorite teachers said--particularly about how Appalachia is treated in American discourse. Generally, though, Kingsolver's directness works well in this novel because of the splendid first person narrative voice. Young Demon Copperhead looks us in the eye and tells us his story. He's a kid, ages ten to early twenties in the book, and even when he gets things wrong, he is unreliable mostly in being too hard on himself.

Kingsolver also gets away with some of her messages because Demon is telling us what he's learning. Sometimes he is reporting a little lackadaisically what other say, and sometimes enthusiastically. It's always a challenge to get opinions and facts into fiction smoothly. I use"challenge" here seriously, not as a euphemism for "problem." In this novel, Kingsolver does it as well as anyone can, with Demon's voice presiding.

The message laid out here is about the opioid crisis in Appalachia, and more broadly in all the poor regions of the United States, and also about the insufferable sneering of the Media and many individual Americans at Appalachian Americans. Demon is aware of the disdain the larger culture often holds for everything Appalachian from accents to life style (including historical Appalachian preference for subsistence living over the pursuit of wealth). Kingsolver makes it clear that the devastation is from the outside: timber companies and coal barons who stripped the region of its resources-- and now Big Pharma.

This latter, the devastation of profitable addictive drugs, is something that anyone with a connection to the mountains is familiar with. I had a young cousin die last year of an overdose of Fentanyl. Many of us, middle class being no barrier, have these direct connections. Kingsolver's people, her imaginative community, are like relatives or neighbors. By nature and by ideology, she does not condescend to people, and that includes junkies.

Let me end with the Dickens connection. Kingsolver writes big, and, as I suggested above, sometimes her stories get a little saggy in the second half, but this novel follows another novel's plot, not too closely, but enough for resonance and structure. I would suggest David Copperfield gives her a path that helps keep her story on track and moving. And this is not a failing but a strength. It follows David Copperfield especially in its love stories. Victorian novels, specifically Dickens, were made for Kingsolver. She's got good guys and the bad guys and social evils and cruelty to children and a host of lovable eccentrics. She uses variations on names and situations from Dickens--the kindly neighbors who often take Demon in are the Peggots; his beloved child wife is Dori. And then, once you've met Angus, if you remember your Dickens--well, that gives you a strong idea of where the love story is going. Turning the overly sweet, soft wifey into a drug addict is a brilliant touch.

There is, also Victorian style, a happy ending. This is not to to suggest it is a happy book, only a hopeful book. The story is strewn with people dead of oxycodene and fentanyl and drunken accidents. There is a wonderful psychopath (like David Copperfield's "friend" Steerforth in Dickens) who everyone falls under the influence of. There is child labor and sexual exploitation and football, which both holds the community together and undermines it.

The community, by the way, is Lee County in the Appalachian west end of Virginia (NOT WEST VIRGINIA! ). My father's family is from there, and other family members of mine are from Tennessee north and east of Knoxville, where a good deal of the novel happens. This adds to the pleasure for me, but doesn't have a lot to do with anything except that I can vouch for at least a baseline of accuracy.

It's a big book, but goes like a houseafire, and makes me think our novels could use more Victorian models and Victorian virtues.

Go Kingsolver!

How about a southwestern Virginia Middlemarch next?

For another points of view, see the New York Times. The Washington Post, the Crimson and The Guardian, which does a nice job with the Dickens connection: "'Angus' Winfield not only has sobriety in the modern sense (she's dead set against drugs of any kind), but also possesses the human qualities that the angelic Agnes [in Dickens] singularly lacks. 'There's much to be said,' muses Damon, 'for lying around with a person on beanbags, firing popcorn penalties at each other for offside fart violations.' Take that, Victorian Angel in the House. Angus is a living and appealing alternative, farts and all, to the Doris and Emmys in a way that Dickens's Agnes never quite manages to be."

Agostino by Alberto Moravia

This small book is pretty much precisely as advertised in Kenneth C. Davis's Great Short Books. Themes and accomplishment, aside, you read this for the journey not the map: that is, the story takes second place to our experience of it. A thirteen year old boy is on vacation at the sea with his mother. He has a wildly guilty passion for her body, which begins with childish worshipfulness, but when she starts an affair with a young young working class man, the boy Agostino falls apart, starts hanging out with a little crew of tough boys who hate him for his relative wealth, and tease him and beat him up. They have an old sugar daddy with six fingers on each hand who makes a pass at Agostino, which leads the boys to insisting he's giving the old guy sex.

It's all sordid and angry and sad, and quite a wonderfully intense hour and a half of reading. Lots of pain, but also energy and passion.

Now I want to read more Moravia.

The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Next on the Kenneth C. Davis's Great Short Books list is one I had read years ago, probably in the very early nineteen-eighties. I never really liked it back then (but it was required reading by an aspiring Second Wave feminist). I couldn't really warm to Edna Pontelllier, especially with all her assumptions about being taken cared of by men and her easy dependence on various servants, all

black as far as I could tell. My only strong memories from my earlier reading were of the beach community and, of course, the swims in the Gulf. And I never accepted Edna's last swim. Edna seemed isolated and the only one of her kind.

I can't say I warmed to Edna much this reading either, but now I appreciate the beach resort, the community life, the view of a woman caught up in a destructive social milieu. I don't know if I got what Chopin wanted me to get, or what the late twentieth century feminist readers got, but I felt the place and time and especially the other characters-- the small, aging, unpleasant but inspired pianist; the wife-and-mother who seems to enjoy the life Edna is rejecting, but who also experiences a normal but intensely difficult child birth almost on stage.

Edna chooses to take a lover and really enjoys sex, but between her enjoyment of sex and the vivid story of giving birth, you understand why the book, published in 1899, famously destroyed Chopin's writing career. Claire Vaye Watkins (see below) says, "Unlike Flaubert, Chopin declines to explicitly condemn her heroine. Critics were especially unsettled by this."

It is then a fine novella, which perhaps is best read with sympathy but not identification with the protagonist. The childbirth and sex are well done, and Chopin did a good job on Edna's two little boys who are completely unsentimentalized little guys, happier (and nicer) in the country than in the city. Edna loves them episodically, but doesn't center her life around them.

Even the ending surprised me with the beautiful inevitability of the sensuality and opened me to see it as an inevitability of the place and time, of the limitations on the bourgeois young wife.

There's a good 2020 essay I'd recommend if you want to think more about The Awakening: "Unlike Flaubert, Chopin declines to explicitly condemn her heroine. Critics were especially unsettled by this." ("The Classic Novel That Saw Pleasure as a Path to Freedom" by Claire Vaye Watkins – adapted from Watkins; introduction to "The Awakening: And Other Stories," from Penguin Classics. Feb. 5, 2020 in the New York Times ).

Ballad of the Sad Café by Carson McCullers

This is the third of my little short novels project. McCullers is pretty much all Southern Gothic here, with entertaining but exaggerated characters who all seem to be living out predetermined roles, like figures in a fairy tale. The focal character is a physically strong businesswoman who is a liitle gender fluid, but inspires a man to lover her and even marries him for a week and a half. Then she falls in love, and eventually her husband comes back, and a showdown ensues.

It's interesting, entertaining reading, but feels like it was supposed to be more serious that it actually is.

(Image of Vanessa Redgrave as Miss Amelia and Cork Hubbert as Cousin Lymon in the 1991 movie.)

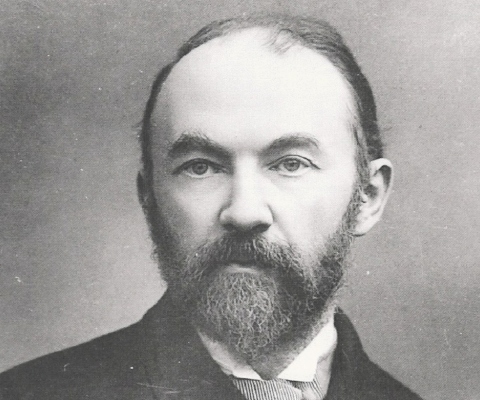

Lincoln at Gettysburg: the Words That Remade America by Garry WillsGarry Willis is an historian and author of a lot of books on politics and history. This little gem, published in 1993, covers the history of the Gettysburg Address succinctly, but focuses perhaps most interestingly on the rhetoric that Lincoln and others employed in the time of the Civil War–its basis in Greek oratorical forms, the mid-nineteenth century cemetery movement (that turned graveyards into beautifully landscaped places for contemplation), and, perhaps most interesting, how the Address was at the vanguard of a revolution in thought about the founding ideas of the United States as well.

I didn't read all the appendices, which include the famous orator Edward Everett's main address at Gettysburg, which went on for a couple of hours.One interesting fact is that Lincoln was never supposed to offer a long peroration–that was the Everett's job. Lincoln was always expected to do a brief few sentences–the actual dedication of the cemetery with all the dead soldiers from the great battle a few months earlier.

There are lots of enjoyable notes about Lincoln coming down the hall of the White House late at night, in his shirt tails to share something funny with his secretaries. But it isn't a book about humanizing the greats, it's about how Lincoln attempted through rhetoric to reorient the American project from the Constitution, with its details and compromises with slavery, to the Declaration of Independence and its clear statement on equality of human beings.

Really worth reading–another one of those books that I can't get through very fast, but so worthwhile.

The Well-Beloved by Thomas Hardy

This was Hardy's final published novel--1897. A different version had been serialized around 1892, then came Jude the Obscure in 1895 followed by this much revised Well-Beloved. It's an odd book to me, a little like a Henry James novella in which an artistic man plays out some fate or low-key tragedy. The artist here is a sculptor who we never see at work. He was born on a tiny stone cutters island in the south of England, where he has a long term relationship with a cultivated island girl, and a fantasy-love life in which a Spirit of Love keeps changing containers, i.e., women. It's pretty airy-fairy stuff to my taste. He deserts his first love, falls for a rich island girl, they run away together, then break up, more or less by mutual consent, and he goes about his shifting passion business.

At the age of forty, he goes back to the island, discovers that his first love, probably his true love, is dead, but her daughter looks just like her, so he falls in love with her for awhile, then leaves, and then, in his early sixties, goes back and tries to marry the daughter, the grand-daughter of his first love.

I can't say I'm enthusiastic about the book, but here's what I like: in the final part, when he's "old," the theme really is old age, and I don't read a lot of that. He doesn't feel his age, or really even look it, but is certainly seen as old by the twenty year old he wants to marry. He rails in his gentle way (really, far more Henry Jamesian than I would have expected from Hardy) and rediscovers the rich island girl he broke up with yea those many years ago.

For him, she takes off her veils, hair pieces, extraordinary make up. And puts her lined face in the sunlight for him. It has a kind of happy ending, probably as fantastical as his love life has been, and our hero focuses his days on local public work–salubrious cottages for workers, a better water supply. Very calm and practical, his tempestuous fire of love died out, his art of no interest to him anymore.

Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy

Now we're looking at the one of the reliable Hardy classics. This was his fourth novel and first big popular hit, with lots of melodrama and suffering but a happy ending. A bold and beautiful young woman takes on the management of a farm for herself, working with an ex-love, but then falls for a bounder (it's a hard book to talk about without spoilers, because every chapter has more plot unfolding, fast).

Hardy's women, even in the The Well-Beloved are often capable and even with touches of the proto-feminist. The women (especially working class ones) seem to be far less restrained that the more middle-class Victorians' women do. Hardy is half a generation younger that the others, and he had cousins who were in service,and everyone when he was growing up was involved in some kind of working with your hands. Sitting in parlors doing fancy work and chatting wasn't really an option. His women seem to have wider stances and more defiant chins.

So this is one of Hardy's relatively cheerful stories, with a sheaf of funny but obviously beloved mechanicals, farm boys and drunkards. So different from The Well-Beloved.

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy

This is, as it is meant to be, a sweet beautiful book about friendship–Boy meets Mole, who is a cheerful humorous character who shares proverbs and other short wisdom. He also likes cake. The book has been a huge best seller, and is

beautifully illustrated. Boy and Mole help Fox who informs them that under ordinary circumstances he would have killed Mole, but Mole chews him free from a trap, and he becomes a mostly-silent, somewhat bemused companion. He's my favorite character.

Next they meet a stunningly beautifully drawn Horse who has even more wisdom to impart and a little magic. He says the bravest thing he ever said was "Help." He's the demi-god who makes everything right.

The hand-lettered text integrates beautifully with the art, but someone a beginning read would be unlikely to be able to read it. I wonder if children like it as much as adults do.

A Complicated Kindness by Miriam Toews

Nomi Nickel is a high school senior whose mother and older sister have run away from their Mennonite community in western Canada. She makes jokes about having no future but chicken killing at a local factory; she smokes

cigarettes, has a boyfriend, does various drugs, skips school–does an infinite number of things forbidden by their branch of what she calls "the Mennos," and yet stays around to take care of her father, a sometimes clueless elementary school teacher who always wears a suit and tie. Towards the end of the book, he also starts selling or giving away all the furniture in the house. The center of his life had been his wife, Nomi's mother, and the church, led with appalling rigor by Nomi's mother's brother Hans, a.k.a. Hands and The Mouth. He puts an even heavier hand on the old traditions of the town, keeping the schools and hospital and church in line, and happily excommunicating/shunning those who don't conform.

It's a poetic story, full of as much of popular music and culture and Nomi and her friends can squeeze into it. It is colored by loneliness as well as creative anti-social behavior, and Nomi's yearning for her mother and older sister.

This is one of those books that meets the promises of its blurbs: it is edgy, different, moving, touching, and it presents love in the middle of a dysfunctional family that seems to be part of a dysfunctional culture.

In the Lonely Backwater by Valerie NiemanThis will be a short review, because we just had a long one in last issue. Ed Davis's review intrigued me so much that I read the book myself and highly recommend it. The voice of Maggie is intelligent and charming, and I love her

passion for her lake and her North Carolina woods as well as the memoir by her Carl Linnaeus, whose Lachesus Laponica, or A Tour in Lapland, written in 1811, is her favorite reading matter.

Even though the novel has a murder, don't expect a standard mystery: Nieman is less interested in violence and her villain than in the flawed but ordinary people around the marina. Maggie's relationship with her alcoholic father is well-portrayed and moving. She may not be able to depend on him to be sober, and she may have to be responsible or herself far beyond what a girl just finishing high school ought to be, but there is also a lot of love there.

The surprise at the end is not my favorite part--I'm not sure I believe it, and I like to feel I can trust my narrators, when I like them, as I do Maggie. Still, like all the best novels, this one is not about its last page, but about the journey and the voice. The great strength of novels, in my opinion, is how we travel intimately with the characters and their lives and their places, and In the Lonely Backwater does this superbly.

TWO BY ELIZABETH STROUT

I Am Lucy Barton by Elizabeth StroutThis is my second read of this short novel, and once again I am impressedand admiring, but don't quite understand the excitement. Four years ago, when I read it, I wrote: "This small novel is direct and compact. The central story line is about a writer with a repressive and deprived early life who now has a mysterious nine week illness that keeps her in the hospital. The heart of the story is about how her laconic estranged mother shows up and cares for her. A lot of things are left open-ended-- the snake when the little girl is locked in the truck, for example--but there is a sparseness to Lucy's life that appeals to me."

This time, the structure appealed to me most, and related to that (and my recent interest in novellas), it's smallness. Lucy's mother's visits alternate with references to parts of Lucy's life she is determined not to write about

in this book, parts of the present and hints of the future. Her mother tells the latest about people in their hometown. Gradually Lucy reveals her odd and dangerous childhood. The present of the story--the story line-- is that the mother comes to the hospital and when Lucy gets better, she leaves. The themes and images and hints are of the relationship of mothers and daughters, the strength of dysfunctional families, a small town, New York City.

For my previous comments, see Issue #199.

Anything is Possible by Elizabeth Strout

I reread I Am Lucy Barton largely because of its relation to this novel I hadn't read before. The Lucy Barton world is interesting and marvelously written, but something doesn't quite click for me. The only thing I can put my finger on is that in spite of all the abuse and horror in everyone's childhood--all seems to be forgiven in the end. Here, Abel, a successful air conditioning business owner who ate out of dumpsters as a child is sweet and loving and gives his life at the end to get his granddaughter's toy unicorn back to her. He is listening to a failed actor who needs an ear. In this scene, and I came about half way to tears, which what I do with all Dickensian orphans, which is what most of Strout's people feel like to me. Things happen in Anythng is Possible like children being made to eat chunks of liver floating in the toilet. Creative torture rather than sexual abuse, the favorite of probably too many twenty-first century writers.

Again, I'll read more of her books, but they aren't on top of my pile.

TWO BY CORA HARRISON

Chain of Evidence By Cora Harrison

I read a recommendation of Cora Harrison's historical mysteries from Tana French, and couldn't find the first books available for Kindle at the library. I usually read mysteries and other genre on the Kindle, loving the speed and ease and not having to pay for them.

Harrison has a couple of series. One features a nun in the 1920's with a lot of Irish Revolution background. The second series I dipped into is in the 16th century (Henry VIII is the young English king). In the latter series, the sleuth is a brehon, a sort of judge/detective, a woman named Mara who administers the old Gaelic law, which seems progressive in comparison to to English law of the time. The Gaelic law seems to prefer fines to drawing and quartering, for example. That's interesting, as is a lot of the material about Gaelic traditions and values. It also has some fun sleuthing by Mara and her half dozen pupils (she runs a sort of apprenticeship/law school too, and-- oh--she's married to a minor Irish king-- not the brightest candle in the chandelier, but a real hunk). The ending has a nice twist, and there is (at least at first glance) murder by cattle stampede. Even though I have a good-humored feeling about it, I was shocked by some sloppiness. So sloppy, I wasn't even sure I was going to keep reading.

It's the ninth in the series, and I always suspect that successful or even moderately successful series genre writers start going too fast, or losing interest, or maybe being pushed by their editors or their fans to finish more books faster.

But this just seemed inexcusable: there was a twenty page passage halfway in that was about three drafts short of being finished. It was loosely written which doesn't necessary stop me because I read these things fast, but the details just collapse. Mara sends her

assistant, Fachtman, on an overnight trip to bring a doctor back to look at their corpse. And while he's away, during scenes when Mara needs something done, Fachtman continues to do chores for her. He pops up as if Harrison just forgot he was away. Mara asks him to pass on a message to the students, to bring her things she needs--and all the while he's miles away! He has no lines, so he's only being used as a tool , but it just sets my teeth on edge like the sound of a dentist's drill.

A Shocking Assassination by Cora Harrison

This book from the Reverend Mother series is written so much better than the 16th century brehon book.

This one takes place in Cork just a couple of years after much of the city was burned by the British-backed Black and Tans. It's really a classic near-cozy mystery with a solid list of suspects to the killing of a corrupt city official in the middle of a morning market (indoors when the gas lights went out). The Republicans get blamed, and they are much in evidence, fighting to have all the counties of Ireland become free of England.

The Reverend mother is a cool character, even as (perhaps) an attempt is made on her life. There's a young Republican girl Eileen who is an alternate POV character, who has adventures breaking a boyfriend out of "gaol," and gives legs to the stately wimpled Rev. Mother.

There's a nice lightness to the telling in spite of death and danger and very heavy political background–the comfort a good mystery gives aficionados, I guess, that our mystery will be solved an our most important characters survive.

And I was truly surprised by the actual murderer!

THREE MORE BY MICHAEL CONNELLY

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly

This is near the end of what Connelly has written about Bosch. The procedural and action here are clear and gripping as always, but Bosch is diminished: the star is Renee Ballard, who has a lot less resonance, even though she gets a new

dog. Harry is an eminence grise, saving her bacon once or twice, but mostly following her lead, is sort of sad.

As always, this one is set n the present of the time of writing, so we've got the pandemic and masking and a demoralized LAPD with criticism of all cops after George Floyd. I know Connelly does his research, so I assume there's something to this. He manages a nice balance of how it feels to be a cop with the usual rotten cops and ex cops causing more crime than they solve. That really is an interesting quality of the books.

The Last Coyote by Michael Connelly

I've read this one a few times. This is where he's on leave for knocking Lt. Pounds through a window, seeing the shrink Dr. Hinijos, and solving the mystery of his mother's murder. It feels so much fresher than the later novels, Bosch's obsession with his calling works. Irving Irwin's emotions are a little mysterious, but Connelly is good on these people who have extremely mixed motives.

These novels from the 90's are when Bosch is angrier and rougher (on perps and himself)–altogether more dangerous and vulnerable and neurotic. By the time he has a daughter, he's a changed man. Still fun to read, but these early ones are the best, and why wouldn't they be? The whole thing with a money-in-the-bank series, I guess, is that people want the product. I wondered if that played into Cora Harrison's sloppiness.

You understand why Connelly wants to try a Bosch first person and to have Bosch a possible crook, and Bosch with his half brother Mickey Haller, etc. Etc. But the first ones are still best.

Trunk Music by Michael Connelly

This 1997 Harry Bosch book is another one that hits the sweet spot: lots of plot, redoubled and twisted; return of Eleanor Wish; both Jerry Edgar and Kiz Rider; AND Lt. Billets. Los Angeles and Las Vegas. A little low life Hollywood (bad film producer turned money launderer), a former beauty now apparently evil, but with a little gold in her heart. Some organized crime, a conflict with the Feds again. Nasty Chastain from internal affairs.

I've been embarrassed in the past about my multiple readings of these books, but I think I see what I'm after–in this case, on the Kindle, I was reading while we were traveling and I wasn't reading much at all, so I would read a couple of pages before sleep and turn away from it easily,

I am also always interested in what works in novels, which probably will never be how I write. And at this point, it is the familiar people, the lulling police procedure, much of it in Bosch's mind as he figures things out, probably in the end more like a writer than a cop, but still interesting.

The Princess Bride by William Goldman

I've been reading about this popular book and the movie made from it, and about William Goldman himself, who was a successful screen writer and semi-successful novelist (well, his books always sold). He wrote screen plays for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid as well as The Princess Bride and for Misery. There is lots of stuff out there (i.e. on the Web) about his Hollywood experiences and relationships with Stephen King and the actors in PB. I read the 30th anniversary edition with the first chapter of Buttercup's Baby, and a lot of other meta material.

I think I'll describe myself as a reluctant enjoyer of the book. Goldman really does/did love all the adventure and excitement and his funny characters ("I am Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die..." as my nearly 4 year old grandson likes to recite).

But I have the feeling Goldman doesn't want to sink all the way in. He doesn't want to look foolish, maybe, to admit he loves the fantasy, so he does his elaborate parody and satire, and intersperses comments from "William Goldman" the screen writer. He's trying to be a cynical sophisticated grown up and a stand up comic (he must have loved working with Billy Crystal on the movie).

I get it why so many people like it, but there's just too much meta armature for me--some of it is hilarious and wildly clever, but I'm willing to believe the tale without the parody and cynicism.

Note on the reaction of the 6 year old big sister of the almost-four-year old: she liked having her father read it to her, but got bored and confused by the meta stuff, so her father skipped it. "Overall, she liked it, although I think it started too slowly for her. She basically wanted to get to the miracles as fast as possible."

Maybe that's the version I wanted.

A Clash of Kings by George R.R. Martin

More rereading. This second book ends with Bran running away with the Frogman kids. Meanwhile, the wildling Osha takes Rickon and the appropriate dire wolf. This is to separate the boys.

Winterfell is a mess; Jon has just gone over to the Free Folk. Tyrion is alive but direly wounded. The Lannisters are in charge at King's Landing; Arya and Hot Pie and Gendry have just escaped Harrenhal. Sansa has been dumped, and is happy but doesn't know what's going to happen to her. Catelyn is at Rivverun with Brienne and Jaime. Major threads left hanging that will return: Stannis's plans; what's going on with Robb.

If none of that means anything to you, please ignore the rest too.

When I read this book the first time, years ago, all these details were mixed with the previous and following books. I was reading so fast that I didn't separate the books in my mind. I still have no idea what happened in what book, although I have these notes on the second book, and the first book had all the character introductions and infamous death of the one who appeared to be the protagonist.

Is it the next book that has the Red Wedding? When does Theon get his mutilation and demotion to Reek?

We Are Not One: A History of America's Fight Over Israel by Eric Alterman Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Joe Chuman writes: "[The] recently published We Are Not One [is] about America's history with Israel. It is by Eric Alterman, journalist, historian and long-time columnist with the Nation. The book is a biggy - more than 500 pages and packed with information. It is critical but tries to steer clear of polemics. Quite an achievement. This review comes with its own video. It appeared... under the auspices of the Puffin Cultural Forum." (See Chuman's interview of Alterman on Puffin's Interview Series here. )

The installation of Israel's latest government, the most right-wing in its history, puts Israel back in the news. But Israel has never been far from the headlines. For a small nation, the size and population of the state of New Jersey, Israel commands attention far disproportionate to its size.

No doubt Israel as a focus of international awareness is tagged to its unique and tightly intertwined relation to the United States. It also results from the world's relentless fascination with Jews, which has served as a basis for prejudice, allegations of Jewish conspiracies, and much worse.

Books on Israel, its history, its origins, and its unique relationship with the United States abound in great numbers. A most welcome addition to the field is a magisterial treatise by historian and journalist, Eric Alterman. We Are Not One: A History of America's Fight Over Israel is a comprehensive work of more than 500 pages packed with information in which Alterman strives to document every episode in America's relation to the Jewish state since its founding 75 years ago. It recounts and goes behind the scene to detail well-known events as well as those which have been mostly forgotten.

Inclusive of Alterman's concerns is Israel-American relations as a matter of foreign policy. But he is no less thorough in his coverage of the relationship between Israel and Israelis to the primarily non-Orthodox American Jewish diaspora. It is from this relation that the title of the book is most likely drawn. In my upbringing as a Jew, I was taught that Jews are a single people, unified by a common sense of peoplehood which needs to serve as a bulwark of loyalty to one's own. This never seemed the case to me, and today it is less true than ever. Israel and American Jewry are stridently divided. Most starkly, as Alterman documents, American Jews remain steadily left of center in their political values and voting patterns. Younger generations of Americans are becoming more progressive. By contrast, Israelis have moved consistently to the right, including younger cohorts of the population. As Alterman notes, American Jews comprise a “blue state” and Israel a “red state.” Indeed,70 percent of Israelis favor Donald Trump. Among American Jews, that number is reversed. This chasm is unbridgeable as never before.

Alterman is also concerned with the role of the press in shaping Israel's image and with major Jewish organizations that serve as a bulwark in defense of Israel and claim to defend American views, even as their positions radically depart from where the vast majority of contemporary American Jews stand on Israel.

I credit Alterman with courage in his undertaking. To write about Israel, or even to render a comment, is to place oneself before a firing squad. Some will upbraid Alterman for being an enemy of Israel. Others will condemn him for being too sympathetic. Still others will contend that he is obsessed with Israel's sins, while soft-peddling criticism of the Palestinians and the existential threats to Israel's security looming just over its borders.

Alterman's voice is that of the historian. He is deeply immersed in the issues, yet he partially floats above them to provide descriptions of events and their actors without becoming ensnared in polemics. This avoidance is not equatable with an absence of criticism. To the contrary, Alterman is a truth-teller committed to getting beneath “official” stories and headlines to reveal hitherto unknown facts and debunk accepted myths.

An early chapter deals with the role that the iconic novel and subsequent film, Exodus, played in framing the image of Israel and the new, post-Holocaust Jew in the American mind. Leon Uris's book, on the New York Times best-seller list for a year, found its place along with the Bible on the bookshelves in myriad Jewish homes. But as Alterman tells us, David Ben-Gurion admitted that the work suffered from the author's lack of talent, and Golda Meir opined that the novel contained “a lot of kitsch.” Both averred, however, that it was marvelous publicity and propaganda for the new nation.

The film version, starring Paul Newman, employed romanticized cowboy motifs, Arabs referred to as the “dregs of humanity,” and it is strewn with historical inaccuracies. But the film was a box office success, and as Alterman notes, “it continued to be shown at synagogue fundraisers, community centers, summer camps, and Hebrew schools for decades to come.” It formatted Israel's image in the American mind in the state's early years while playing fast and loose with historical verities.

Interesting facts abound. They are too many and too complex to recount, but a few I found of particular interest. New to this reviewer was the role of Harry Truman in supporting Israel's birth. Truman, coming from Missouri, harbored usual anti-Jewish prejudices, knew little about Palestine before becoming president and was certainly no Zionist. Yet, as Alterman makes clear, Truman had Jewish friends, a warm relationship with Chaim Weizmann, and was deeply moved by the plight of Jews in post-War displaced persons camps. It was emotion, more than political principles, that caused Truman, in the face of opposition from his State Department, to declare his support for the State of Israel just minutes after David Ben-Gurion declared its independence. As such, America's ties to Israel were launched at its very creation.

The `67 War was a watershed event that changed the image of Israel in the minds of different political factions. It would be useful to quote Alterman here:

“Before 1967, Israel had been understood to be a progressive cause, and the Arabs a regressive one. Israel had successively positioned itself in the anti-imperialist camp and had enjoyed good relations with other emerging nations, especially those in Africa. The socialist orientation of its dominant party, together with the 'David vs. Goliath' global image to which it had attached itself vis-a-vis the Arab world placed it within the geography of the 'good guy' camp for most liberals and leftists...”

“Regarding Black-Jewish relations pre-1967, US civil rights leaders, including, especially, Martin Luther King were almost uniformly pro-Israel...”

“The Six-Day War said 'good-bye' to all that. The cause of the Palestinians had long been part of the Marxist-inspired 'third-world' international revolutionary vanguard that included North Vietnam, Cuba, Nasser's Egypt, and other non-aligned or pro-Soviet governments opposed to the Americans and their allies...The Black-Jewish alliance had endured for more than half a century...Now the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a New Left civil rights organization, began publishing articles reporting on what it called Israel's conquest of 'Arab homes and land through terror.'”

Much else changed with the `67 War and factions and political dynamics concerning Israel have grown increasingly divisive and strident. The War enabled the settlement of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, and with the rise of the Likud Party, Israel has moved increasingly to the right. A contributing cause, no doubt, was Palestinian terrorism and the two intifadas which marginalized the Israel peace movement. In addition, the Orthodox sector of the population has grown and augmented its political power.

Alterman's treatise, which is presented chronologically, details in great complexity episodes in Israel's history and the involvement of a string of actors who were responsive to changing conditions and competing political dynamics. Nixon was known as an antisemite, but his bigotry's pervasiveness and crudity are shocking. Alterman cites Kissinger's discomfort with Jews, despite his own Jewishness, as he engaged in shuttle diplomacy. The author brings us back to the “Zionism is racism” controversy played out at the United Nations, and the role of Daniel Moynihan, which helped launch him into the senate.

Jimmy Carter and the Camp David Accords rightly receives a chapter that includes the painful controversy occasioned by Andrew Young, Carter's UN ambassador, when Young held a secret meeting with a Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) official. The meeting led to Young's forced resignation, which heightened Black-Jewish tensions. But, as Alterman often makes clear, such controversies were more complex than they were reported at the time: There had previously been private meetings between US officials and the PLO, which did not create a stir.

Lebanon, the massacre at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, and the complicity of Ariel Sharon are described in their complexity, as well as the allegations that the Iraq War against Hussein was pursued for Israel's benefit.

I found of special interest Alterman's chapter on Barack Obama. Its title “Basically a Liberal Jew,” was taken from a remark jokingly made by the president to an audience at New York's Temple Emmanuel in 2018. It's my view that Obama is a philosemite whose political career was launched in Chicago with the support of Jewish friends and associates. Though he has disagreements with Israel, it was Obama who had inscribed into law more than $3 billion given annually to Israel, which enabled Israel to construct its Iron Dome defense system, deployed to protect the state from incoming missiles from Gaza. Despite an unprecedented commitment to Israel's security, the contempt for Obama coming from Israel and the calumny issued from the Jewish establishment has been exceedingly harsh. No less has been the contempt for Jimmy Carter, who brokered the Camp David Accords,that generated the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt. Egypt comprises almost one-half of the Arab world, and one would think that Israel and its American supporters would be eternally grateful. But because Carter has been critical of the occupation, he has been the object of almost unmitigated calumny by those who have set themselves up to speak for Israel's interests, and by extension the American Jewish community – which they do not.

Such criticism opens the door to another major theme treated in Alterman's book, namely the exceptionless defense of Israel by conservative apologists no matter how indefensible Israel's conduct may be. Among the major voices in that camp are the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA), and the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations. There are multitudes of individuals in the press, journals of opinion (Commentary the most noteworthy), and among neo-conservative pundits who also hold apologist views.

Criticisms of Israel's treatment of the Palestinians, the injustices and humiliations generated by the occupations, and abuses perpetrated by the military or by settlers, often with impunity, swiftly result in efforts to marginalize the critics. Very often there are charges of antisemitism, even against critics who are otherwise supportive of the Jewish state. Those pointing to Israel's excesses are summarily placed in the same category as those who wish to do Israel harm, blindly forgetting that criticism can be rendered in the service of positive support and care. Arguments that require an appreciation for detail, nuance, and complexity are subject to polemics and crude reductionisms. To this reviewer, it has long appeared as an odd and tragic state of affairs for a culture that has long been characterized and enriched by dialogue, engaged discussion, and a non-dogmatic stance in search for truth to avoid constructive criticism.

This obdurateness is rock solid and forms the basis of policy deployed by AIPAC when lobbying Congress, and is voiced in support of the Israeli government and its American allies. The political stance of Israel's defenders perhaps reached its most extreme manifestation in right-wing Jewish advocacy for Donald Trump in his alliance with Benjamin Netanyahu. The following is an illustration of where die-hard support for Israel has arrived. I cite from Alterman's chapter aptly titled, “Coming Unglued.”

“Trump's extraordinary largess to the Israelis was due in part to the similarities in how he and Benjamin Netanyahu viewed the world...Both politicians were profoundly corrupt...Both leaders displayed degrees of racism, nativism, and ethnocentrism that were considered extreme even by the standards of the racist, nativist, and ethnocentric parties they led. Politically, both were aspiring authoritarians who were eager to forge alliances with fellow illiberal politicians consolidating power based on ethnonationalist appeals in places such as Russia, Turkey, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, the Philippines, Brazil, Egypt, Oman, Azerbaijan, the Gulf States, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere. Neither evinced any patience, much less respect, for democratic niceties such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, or the separation of powers...Common enemies bred friendships of convenience. Netanyahu repeatedly excused Trump's antisemitism and that of his political allies. So did Trump's Jewish supporters, who were willing to make the same tradeoff that had appealed to the neoconservatives of a previous generation, when they had chosen to embrace antisemitic but pro-Zionist evangelical preachers beginning in the 1970s. As long as Trump was willing to indulge Netanyahu, they were willing to indulge Trump.”

The Trump-Netanyahu alliance is emblematic of where Israel has arrived. Israeli society and American Jews, except for the Orthodox (who comprise only ten percent of American Jewry) could not be further apart. With regard to political and social values, they reflect inverted images of each other. As noted at the beginning of this review seventy percent of Israelis, including the younger generations, support Donald Trump. With American Jews, it is the opposite.

Netanyahu is in the Prime Minister's office again, this time beholden to ominous reactionary forces that promise to undermine and transform Israel's democracy and its democratic institutions. In the past election, the Labor Party, the party of Israel's founders and founding vision, won but three seats in the Knesset. Meretz, the left-wing party, none.

As Americans move further to the left, Israelis move further to the right. The American Jewish community holds very little in common with their Israeli counterparts. It's a multi-tiered tragedy. I have personally known people of my parents' generation who devoted their lives to Israel and the Zionist cause. It was their guiding passion.

In a sense, Israel had always held them in contempt: eager to accept their support, while, in line with Zionist ideology, disparaging diaspora Jews for refusing to make aliyah, that is coming “home” to Israel, where they could be fulfilled as Jews. Today that contempt has been more fully realized.

Since evangelicals have revived their commitment to “Christian Zionism” they proclaim a special love for the Jewish people and for Israel. Their theology dictates the Jews need to be regrouped in the Holy Land to jump-start the second coming of Christ, at which point they will either be converted to Christianity or die. Israel has been willing to accept the “friendship” of evangelicals who support it with millions of dollars, assist in the immigration of Jews to Israel, and aggressively support the most right-wing and militarist objectives of the Israeli state. A tragic reality is, given that the evangelical population is many times that of the number of American Jews, Israel no longer needs the American Jewish community for its support. American Jews will increasingly be treated as irrelevant to Israel's interests.

In conversation with Eric Alterman, he opined that the breach between Israel and the American Jewish population (except for the Orthodox) cannot be reconciled. They are moving in the opposite direction and he believes the situation is hopeless.

Alterman further believes that American Jewish leadership for the past several decades has been committing a grand mistake. It has striven to construct Jewish identity on the two pillars. The first is reverence for the memory of Holocaust victims and the other is support for Israel. Yet, the Holocaust is long ago, and as his book makes clear, there is less in Israel to admire.

For Alterman, this current state of affairs opens up new opportunities. It provides a moment in which self-identified Jewish Americans can work to revive and rediscover the riches of their own traditions, religious and cultural. In such a turn, there is very valuable work to be done.

We Are Not Alone does not provide solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, nor, as suggested, does it offer ways in which Israel can resolve its internal problems, or how American Jewish organizations can relate to Israel with greater integrity as we look to the future. As stated, Eric Alterman's exhaustive treatise is a work of history, meticulously researched, honestly presented, lucidly elaborated, and eminently readable.

It is necessary reading for anyone who wishes to achieve greater insight and understanding into a central dynamic of American foreign policy and the place of Israel in the political life of American Jews.

COMMENTS IN RESPONSE TO THE LAST ISSUE

Jayne Moore Waldrop writes: "I enjoyed your Walter Tevis review. He was a great writer and now a Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame inductee. Here in Lexington we're closely connected to his writing, especially the early work done while he lived here or later work set in central Kentucky. I thought you might appreciate this story about the creation of the Harmon Room at the Lexington 21c Hotel. https://www.21cmuseumhotels.com/lexington/blog/2021/the-harmon-room-at-21c-lexington/ "

David Weinberger says, "Great issue of your newsletter....Exceptional! I loved the mix of genres, the books that were turned into movies, your engagement with the 1619 Project, the Twilight of the Self review, the photo of Paul Newman, and so much more."

Donna Meredith writes: "The 1619 Project has been on my To-Read list for some time, and I hope to get to it this year. I think Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste and The Warmth of Other Suns probably cover a lot of the same territory. They are also excellent eye-openers—full of facts we need to know."

Eddy Pendarvis wrote to share a "quip about Henry James that I read in Dan Simmons' novel, The Fifth Heart. The narrative is quoting a friend of James who supposedly said of his writing that far from biting off more than he could chew, he chewed more than he bit off. I love that, as James' style is so frustrating to me in all but his most action-filled works (like The Turn of the Screw)."

BELINDA ANDERSON SUGGESTS THE 1619 PROJECT FOR CHILDREN

Belinda Anderson points us toward some excellent resources for children that have been developed out of (or are related to) the 1619 Project:

The 1619 Project: Born on the Water

This is a picture book in verse, written by Nikole Hannah-Jones & Renee Watson with illustrations by Nikkolas Smith. The audio version is read by Nikole Hannah-Jones

Belinda also suggests

Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, by William Loren Katz. The 2012 edition of this nonfiction book is aimed at teen readers.

Black Past . This website is one of many with lots of material--written and illustrations for learning.

MORE BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

Belinda Anderson also made this recommendation: "It is a book that would make a wonderful gift, for both children and adults: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, written and illustrated by Charlie Mackesy. [See my response above.]

"This is a famous excerpt from the book:

"“What is the bravest thing you’ve ever said?” asked the boy.

“Help,” said the horse.

“Asking for help isn’t giving up,” said the horse. “It’s refusing to give up.”

'Here's a passage I particularly liked:

“Is your glass half empty or half full?” asked the mole

“I think I’m grateful to have a glass,” said the boy.

"It is a book quietly illustrated and kindly written about friendship and learning to let yourself be yourself."

MOLLY GILMAN RECOMMENDS KAGE BAKER'S NOVELS

In the distant future, two incredible discoveries were made—each alone, useless. First: the secret to time travel—but only how to travel backwards and return to the moment of departure. Second: the secret to immortality—but the procedure could only be performed on young children, who were not the ones with the vast wealth to afford it. Then one pioneer, known only as "Doctor Zeus", realized how to combine them. If one could send agents far, far back in time, and create immortals to live forward through history, those immortals could work to preserve "lost" treasures and otherwise cache great wealth for their future masters.

It worked, and Doctor Zeus Incorporated, aka "The Company", became (…WILL

become?) the most rich, powerful, and secretly influential force in all past and future. The books of The Company series follow these immortal beings, who live in real time through the past with limited knowledge of the future, trying to find fulfillment in their work while dealing with the burden of knowing how everything, and everyone, around them will end.

I always marvel that Kage Baker isn't up there with Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov of the science fiction greats. Her syntax is beautiful, her characters are dazzling, and the books' vivid sense of place is exquisite, especially prehistoric California. She was, among other things, a teacher of Elizabethan English, so no wonder the early books—which can only be classified as Historical Science Fiction—are so immersive. As the series proceeds, the other time periods seamlessly transition from known to the unknown and all feel just as grounded. I wish she was just on the other side of the gender revolution in having more of her characters being female, but her central heroine, the botanist Mendoza, is brilliant and carries the series. I take every opportunity to recommend this series, especially book one, "In the Garden of Iden", a great introduction which stands on its own well, and my personal favorite: book three, "Mendoza in Hollywood", for its lush immersion in nature. But the future books are stunning as well for the world-building and characterization. More people should know and enjoy this fantastic storytelling.

TROY HILL ON ISAAC BABEL

I first read Babel late last winter in an online class and group called Story Club led by the short story writer George Saunders. We read and discussed Babel's famous war story, "My First Goose," which felt all the more immediate given

the recent invasion of Ukraine.

This summer I serendipitously happened upon a 1950s translation of the complete collection of Babel's short stories in the giveaway pile at our local dump and took it home. One story moved me in particular. I thought about writing something about it online and posting the story for public access but realized it isn't quite old enough to be in the public domain and translations restart the copyright clock. At any rate, I still felt inspired to type it up and send it out to a few folks who might also get something out of it, and it seemed like a good Christmas-time activity given the nature of the story.

Born in a Jewish ghetto in Odessa in 1894, Isaac Babel became a journalist and a writer of short fiction. His short story collection, Red Cavalry, was inspired by his experiences in the Polish-Russian war of 1920, where he served as a war correspondent and a supply officer in a Soviet regiment. Red Cavalry was published in the Soviet Union 1932 and, in the early 1930s, 0Babel was regarded as one of the most promising talents of Soviet literature. Ultimately, however, his ambiguous, expressionist style came to be at odds with the social realism endorsed by the state. Out of favor, he was arrested in 1939 by the NKVD (a previous version of the KGB), accused of espionage, and executed by gunshot in 1940.

Most of the stories in Red Cavalry depict the brutality and violence of war."Pan Apolek" stands out in this regard. The narrator of this story is stationed in Poland, residing in the house of a fugitive priest who has fled the Soviet Cossack battalions, but where the priest's housekeeper, Pani Eliza, remains. ("Pan" and "pani" are the masculine and feminine forms of a Polish honorific meaning "master" or "lord"—something akin to "mister" and "madame.") Under this roof, the narrator meets Pan Apolek, an itinerant painter who paints biblical scenes and portraits for money and travels with a blind accordion player. We learn that when Pan Apolek first came to town thirty years prior, he was hired by the local priest to decorate the village's new church. Once his murals are revealed and it's clear that Apolek painted local peasants in the image of the saints, including a trampy local Jewish woman as Mary Magdalene and a "lame convert" as St. Paul, he is declared a heretic by the Catholic church while becoming a hero to poor villagers. Toward the end of the story, back in the present, Pan Apolek tells our narrator "an unthinkable" secret gospel.

Here is a story written by a Jewish Odesan, serving among Cossacks (generally known to be anti-semitic), in an atheist Soviet army, stationed among Polish Catholics. From this swirl of ethnicities, nationalities, and conflicting beliefs, and despite the narrator's "bitter scorn for the curs and swine of mankind," emerges a tale of mysterious empathy.

You can check out a...recent translation of Red Cavalry by the esteemed Boris Dralyuk, who has also translated the contemporary Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov (among others).

SHELLEY ETTINGER'S YEAR'S BEST READS 2022

The City We Became & The World We Make, a duology by NK Jemisin

Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

Milkman by Anna Burns

The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan

The President and the Frog by Carolina De Robertis

Shelley says, "My reading life still hasn't recovered to its pre-pandemic pre-Texas levels, still not reading as much and still reading much more crap than I used to, but I did manage to read some gems, and these are the best of them. The San Antonio Public Library system is a bright spot, really wonderful. Looking forward to a year with a book and a dog sharing my lap."

SPECIAL FOR WRITERS

Jane Friedman's excellent free newsletter Electric Speed suggests a web site for finding weather from the past for your nonfiction and historical fiction or just if you always wondered what the weather was like the day you were born: Wunderground provides hourly weather history going back to 1930.

Nikolas Kozloff sends us another article on writing by AI--a pretty even-handed piece-- an interview of indie para-normal cozy writer Jennifer Lepp who sees the bad and the good. [And... Another controversy continues: Fiction as the new flashpoint in the culture wars:

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/why-fiction-is-the-new-flashpoint-in-the-culture-wars-cp8f0jkmp]He follows up with article on the infamous American Dirt scandal--the scandal being cultural appropriation? Or, cancel culture? Interesting, either way. Also, take a look at some thoughts on the issue in my occasional online journal A Journal of Practical Writing.

Some of the pieces from The New York Times may have paywalls.

Check out Odyssey Writing Workshops. They are an in- person and online writing school aimed at science fiction and fantasy writers: not cheap, but extensive in their offerings, which include marketing webinars and beginner level classes on character, dialogue, scene, etc. The prices range from under a hundred dollars (for a two hour webinar licenced for 60 days) to multi-class $2500 packages. A typical single class is around $250 for four sessions.

Reviews of these classes are welcome.

More Hints from a Professional Editor by Danny Williams

Got a nice novel manuscript in the shop this week. Has some mildly magical elements—something more than natural, but way short of dragons and crystal balls.* About half of it is set in 1860 or 1861 Virginia, on a quite wealthy horse breeding, trading, and racing concern. It's very carefully written, and even with my nearly pathological attention to detail I couldn't catch the author in a timeline slip or a substantial tense shift or anything.

Most of my advice was to take greater advantage of the setting, an opulent estate in the final years of the Virginia slave economy. There was a magnificent plantation mansion, and gala feasts and dances. Don't just say the woman was dressing for dinner, tell me about her gown, bustle, wig, or corset. The gaily clad menfolk, too. And that feast—what's on the table? All the bounty of farm, ranch, orchard, and sea are withing reach, so tempt me with some. And that opulent mansion, I want to hear about its colonnaded veranda, English oak woodwork, and manicured landscape.

The author had written some nice old-time-sounding dialogue, and I encouraged him to do more. Many of the suggestions I've actually learned in my academic study of Appalachian speech, which differs from modern Standard American English largely in its retention of obsolescent syntax.** Adding essentially meaningless auxiliaries to verbs: I might could do that. Other quaint redundancies: I like these ones. Using "anymore" positively, and "of" with times and seasons: Anymore, I like to sleep later of a morning. And one character was visiting horseman from Louisiana, so I would give him a little belle femme, merci, excusez moi, and à tout a l-heure.

Speech idiosyncrasies can add differentiation to dialogue. An individual might be prone to throat-clearing before speaking, cursing, or substituting long or obscure words for simple ones. A former co-worker ended every sentence with rising pitch, so every utterance sounded like a question. Nowadays, in every group of speakers there's probably one who begins every remark with "so." All these tools are obvious, but it requires awareness and effort for authors to prevent dialogue from sounding like their own.***

Maybe my input will prompt the author to reexamine the manuscript, maybe not. I honestly do not care much. This work brings me joy.

* Paola Corso, Giovanna's 86 Circles and Other Stories. Twenty-some years ago I had the pleasure of reading the manuscript of this collection. Ms. Corso's habitual setting is urban Appalachian, a much under-recognized genre, and many of these stories feature just this type of quasi-magical touches. Sadly, in the end I was denied the opportunity of working with this gifted fiction writer, poet, and photographer. University of Wisconsin offered her a quite modest advance, and my tightwad director would not allow me to match it. (No budget concerns on his pet projects, of course.) Anyhow, read this, and more of her work, for enjoyment and for instruction.

** Walt Wolfram and Donna Christian, Appalachian Speech. After all the years and scholarship, this slender 1976 opus is still the place to start on Appalachian (or other old-timey) dialect. Quite possibly it will be as far as you need to go with the subject, sparing you some of the more ponderous tomes.

*** Must mention Ken Sullivan, former long-time editor of Goldenseal magazine. He had a real knack for taking submissions from all types of informants and somehow doing a great job of editing while keeping the writer's individual voice. I try to keep him in mind while doing my own work.

Send me some of your stuff—vague notions or developing manuscripts. I'll put a couple hours into checking it out and giving an opinion, for free. I would do every editing job in its entirety for free, except that I'd get so immersed I would have no time for cleaning the bird cage or showering.

Danny Williams, editorwv@hotmail.com (See one of my other personae at Facebook Page "Sassafras Music Shop.")

GOOD READING & LISTENING ONLINE

Joe Chuman has some excellent context on Anti-Semitism.

Excellent story by John Loonam now available on the Summerset Review.

Lewis Brett Smiler's story "Down the Stairs" is on Creepy Podcast . The podcast is an hour, but his story only takes about 34 minutes.

Good list from Emily Temple at LitHub of her Best Books from the past that she read in 2022.

The Hamilton Stone Review, # 47

Mitch Levenberg reviews Carolyn Hagood's long essay weird-girls-writing-the-art-monster

Excellent introduction to Robert Gipe by his friend Wesley Browne in Undermain.art. See our review of his illustrated novel Trampoline here.

December 2022 Issue of Savvy Writer has a good list of memoirs that deal with grief.

MSW reviews "Foote" A Mystery Novel," by Tom Bredehoft at Southern Literary Review, November 2, 2022.

Norman Danzig's story "The Angel of Death" has just been published at Blue Lake Review.

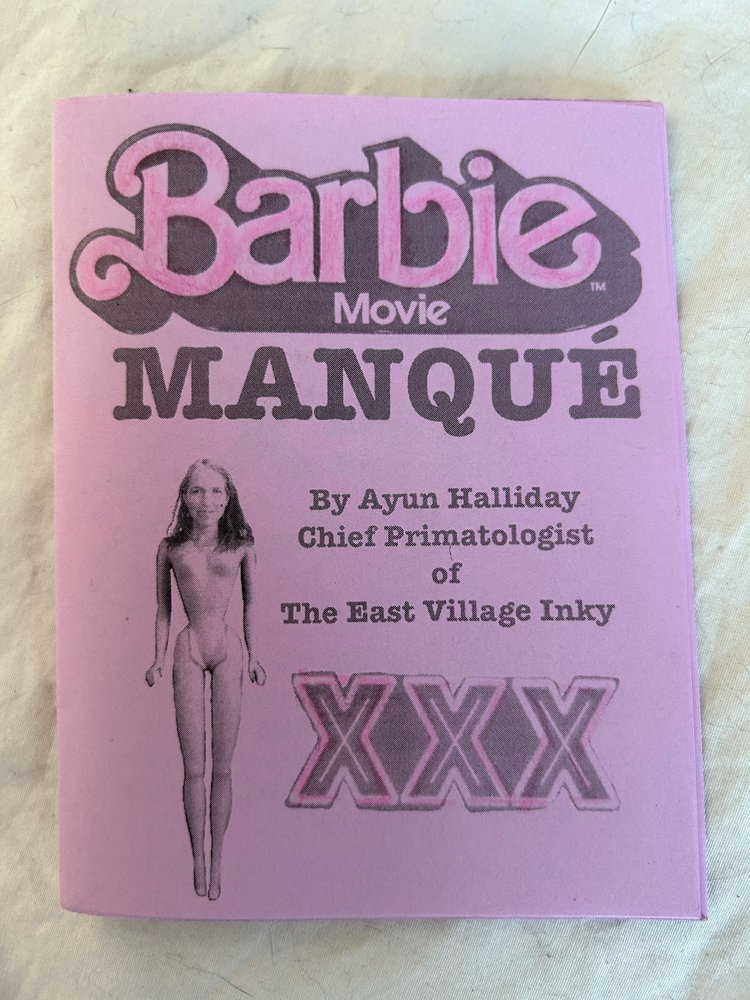

Ayun Halliday's web page: She makes cartoon-style hand lettered publication--doing things no one else is doing.

Kelly Watt's short piece "Next Exit" is up for an honor!

Troy Hill has new stories online: The Write Launch published his long story "Aquarium Life" and The Bangalore Review published his story "Ford Man."

HOW TO HELP WRITERS IF YOU LIKE THEIR WORK

Do you have a favorite author? Are you a writer who wants to do a favor for other writers–andmaybe they'll do a favor for you?

Here's how:

• Write an Amazon review. Go to Amazon.com and search the book you recently (or a long time ago!) read.Click through to its Amazon catalog page. Scroll down below the ads and the editorial reviews and product details to Customer Reviews, and then scroll a little farther to REVIEW THIS BOOK.

• You don't have to have bought the book from Amazon.

• They may ask you to set up a reviewer's account. You only have to do it once, and you can stay anonymous if you choose or make up a handle.

• Give the book as many stars as you reasonably can. I rarely review books I can't give five. Inflated grades? For sure, but this is about publicizing books we enjoyed and admired.

• Write a review. Short is fine. In fact, short is probably better than long on Amazon. You can reuse the review on GoodReads and Barnes & Noble and anywhere else.

• Don't use foul language. They won't publish a review if they don't like the words in it, and they can be heavy-handed. It's a 'bot "reading" the review, not a person.

You will be doing literature a favor, and all of us with books in print thank you in advance!

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 226

March 28, 2023

This Newsletter Looks Best. and its links work better, in its Permanent Location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis ContactFor functioning links and best appearance,

go to our permanent location.

Eddy Pendarvis on Free Indirect Discourse.

Article at At A Journal of Practical Writing

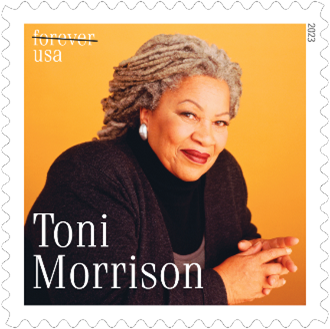

Above: Walter Mosley; stamps of Toni Morrison and Ernest J. Gaines!--and Valeria Luiselli betwen the stamps.

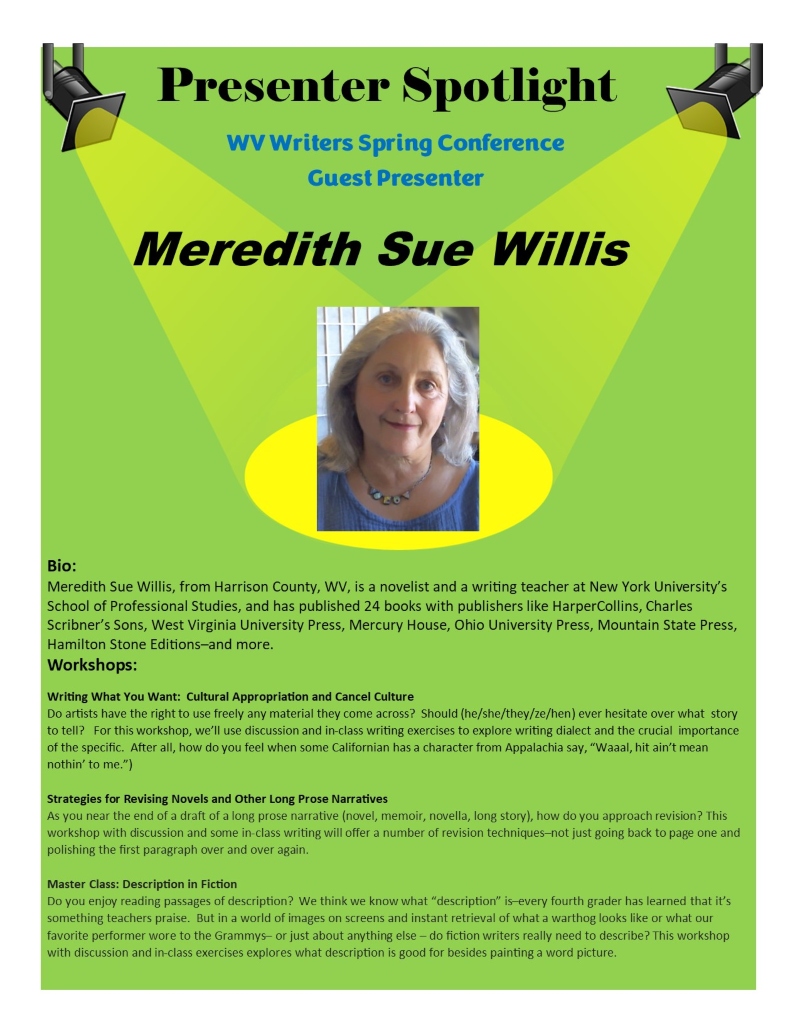

Now available: schedule for the West Virginia Writers Conference, Cedar Lakes Conference Center, Ripley, West Virginia, June 9- 11, 2023. To see workshops and presenters, scroll down to "Spring Conference 2023.

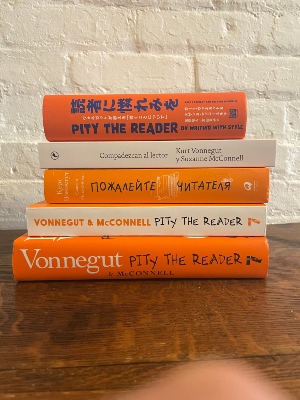

Suzanne McConnell's book of writing advice from and exercises based on Kurt Vonnegut's work is available in four languages already (English, Spanish, Russian, and Japanese) with Polish, Catalan, and Chinese coming soon!

Comments from Readers

Announcements

Lists

Reviews in this Issue

Read/Watch/Listen Online

Notes Especially for Writers

REVIEWS

This list is alphabetical by book author (not reviewer)

In the Garden of Iden by Kage Baker

The Walk to the End of the World by Suzy McKee Charnas

Angel's Flight by Michael Connelly

The Adventures of Jake A Coal Camp Boy by Victor M. Depta

Christianity's American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative and Society More Secular by David Hollinger Reviewed by Joe Chuman

The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli

A Storm of Swords George R.R. Martin

Without Warning: The Tornado of Udall by Jim Minick

Fortunate Son by Walter Mosley

Parishoner by Walter Moseley

Bonjour Tristesse by Francoise Sagan

Lincoln by Gore Vidal

Christianity: A Very Short Introduction by Linda Woodhead

Uncle Tom's Children by Richard Wright

I want to call attention to the announcements section below with a number of exciting new books, some reviewed or to be reviewed in this newsletter. Also check the good reading online list. This includes stories and reviews and the latest article in my occasional publication, A Journal of Practical Writing, an online-only journal with concrete tips about writing and publication--revision, action, point of view, cultural appropriation, hints from a professional editor, a method for outlining, revision techniques for novels, and a lot more. The article is by Eddy Pendarvis, and it's called "Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once?" It gives an excellent analysis of one of the important ways of telling stories in modern fiction.

The first review is of Jim Minick's excellent, just-published nonfiction book about a devastating tornado in the 1950's. This is timely in spring 2023 with deadly tornados hitting the South, and also of personal interest to me because of the tornado that ripped apart my hometown shortly before I was born.

Please let me know your reaction to any of the articles here-- as did these readers in the Comments from Readers section.

Finally, there's an interesting Lit Hub piece about Tim O'Brien's Lake of the Woods and how it changed the writer's career. My review of the novel in Issue # 218.

Without Warning: The Tornado of Udall by Jim Minick

The Udall tornado struck on the night of May 25, 1955, and it was the worst ever in Kansas, killing nearly ninety people within the city limits of Udall, an all-American small town like the setting for dozens of movies and t.v. shows of the era. It had a water tower, kids on bikes tossing newspapers onto porches, a part-time mayor everyone knew personally, several protestant churches, and a handful of stores.

Minick makes a portrait of a town and its disaster into a highly gripping story. The first third of the book with brilliant simplicity just tells the stories, hour by hour: there is a bridal shower in the community center; people worry about the threatening weather; the radio warns of storms, but not tornados. It hits unexpectedly, heralded by heavy hail and the infamous sound of a giant freight train. Some people get into their storm cellars (this is Kansas, after all, so many families had them). Teen-aged Bobby Atkinson is knocked out and wakes up with a broken leg, two broken arms, a smashed hand, numerous bits of wood and rubble in his skin and flesh--and a two by two board plunged in his back, puncturing a lung and injuring other organs. He doesn't know the extent of his injuries, but knows he is all alone in the rain and drags himself for help, not knowing most of his family is dead. He takes shelter in the family car for a while, and is discovered by a neighbor– who flashes a flashlight on him, asks how he is, and then leaves. Minick in his epilogue considers this incident closely along with other moments that could have gone worse or better, right or wrong, that would have changed this history.

Bobby is just one of many people who we follow through the storm: one family in a storm cellar chops through debris to let another family in. People are stripped of every stitch of clothing, babies and young children smashed dead. The elderly and the little ones were most vulnerable.

Minick's stand-out characters are probably Bobby Atkinson with the broken bones and Mayor Earl "Toots" Rowe whose boss gives him six weeks off to help organize the recovery. Toots leads people searching through the rubble, talks to the media, and, perhaps above all, convinces everyone that if they just work together they can rebuild their flattened town and recreate their community.

Another large chunk of the book is the rebuilding, the year after the tornado, which is not as breathtaking as the night of the tornado, but in some ways perhaps even more interesting. It details the support that poured in and the ordinary and extraordinary efforts and kindness of people to one another. There are a few incidents like the man who abandoned the wounded Bobby Atkinson teenager, but more of the story is about making common cause and helping out your neighbors.. Money is raised from the region and the nation. Large groups of Mennonite men, trained in disaster relief as conscientious objectors come and help with the search for bodies. The Red Cross is there and the Salivation Army and the National Guard. Unions send volunteers to put up houses, and churches and other organizations send donations.

Almost unbelievably, the schools are rebuilt in time to have classes September, four months after the tornado. Homes go up in weeks and months, and the businesses downtown. It's a town of only 1,000 people, but still, that is a lot of structures. It is in the end, an astounding and inspiring community and government partnership that rebuilds Udall.

The last part of the book is about commemorations and forgetting.

Minick reminds us that the Udall Tornado was just ten years after WWII ended, and that it was also in the middle of the Cold War. People feared nuclear holocaust and had fresh memories of war. They were trained in civil defense and ready to work together. That sense of commonality also makes it a time many Americans look back to as The Golden Age: small towns where you knew your neighbors; strong family structures, men generally considered the heads of families. Women who worked outside the home were teachers or perhaps post mistresses or clerks in a family store. People theoretically knew and took strength from their place, both the town and their role in it.

Minick doesn't make this point directly, but it is also clear that this was a largely homogeneous demographic. As far as Minick tells us, and his exhaustive and excellent research suggests that he didn't miss a lot-- everyone was white. Many people weren't that many generations from immigration, but the War had forged a common identity. So while the wonderful outpouring of aid and support was partly natural human kindness, it was also the natural human tendency to identify with those who are most like us. There was enormous camaraderie and communal identity with these small town European background white folks in their familiar roles and lives.