Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 222

July 11, 2022

This Newsletter Looks Best in its Permanent Location Online!

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

This Newsletter looks best, and the links work better--

in its permanent location

Online Summer 2022 Workshop

with Meredith Sue Willis!Saturday, August 13, 2022

10:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. by Zoom!The Big Picture:

Structuring the Long Prose Narrative

$100.00 fee includes a critique by MSW

of up to 1,000 words from your project.

For information, click here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issue # 222

If not otherwise noted, reviews are by MSW

.

Reviews

Announcements

Read/Watch/Listen Online

Especially for Writers

Fantasy, Crime, and Science Fiction

Irene Weinberger Books

REVIEWS

This list is alphabetical by author

Dawn by Octavia Butler

Dark Sacred Night by Michael Connelly

The Night Fire by Michael Connelly

Ruth by Elizabeth Gaskell

Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell

The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin

The Killing Moon by N.K. Jemisin

Eleanor and Franklin by Joseph Lash

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers

Family Furnishings by Alice Munro

Jane and Prudence by Barbara Pym

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Summer 2022

I'm getting a lot of pleasure out of my reading this summer--books of my own choosing rather than student work. I also enjoy and certainly learn a lot from work-in-progress, but when I read it, I'm working. When I'm reading my own choices, I am climbing on a raft and floating downstream. Sometimes I encounter the thrill of rapids, sometimes it's a drifty dream, but I'm always in some other place in the universe.

This issue I'm sharing a several months project of reading Joseph Lash's carefully researched and affectionate portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt, mostly, but of Franklin too. The vicious politics of those days is instructive today, but also depressing because back then, there really did seem to be some agreement about the dignity of people (at least white men in tailored suits). There was also lip-service to public service (sometimes too much in the line of noblesse oblige). But read my full report below.

I have also been reading over time, and finally finishing, a large collection of Alice Munro stories, Family Furnishings. Many of them are great works of art. I enjoyed new science fiction too, N.K. Jemisin The Killing Moon, and old science fiction--the brilliant first volume of Octavia Butler's science fiction trilogy Lilith's Children. I also read my first Barbara Pym novels, quite a lot of fun in limited quantities, and for Victorian lit, two Elizabeth Gaskell novels. My happiest discovery was a book I had overlooked, Carson McCullers' The Member of the Wedding, If you missed it, do put it on your list!

I'd love to hear from readers of this newsletter about what you're reading, and how you choose. A list, a paragraph, an essay? I'd welcome having it. We can't assume everyone will love what we love, but how can we know if we don't share our suggestions?

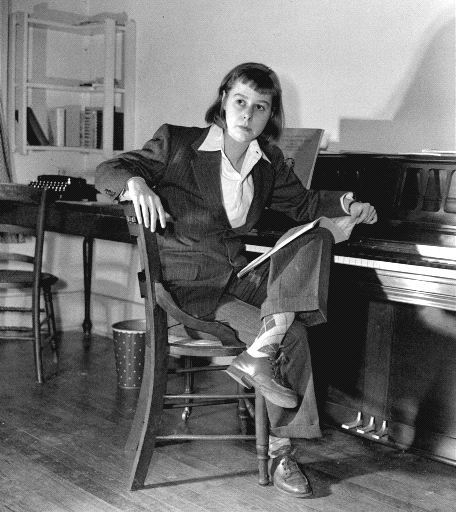

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers

I'm awed by The Member of the Wedding, especially the powerful scenes with Frankie, Berenice, and John Henry. It's all super southern summer heat, sensuality, smells, race, gender, and yearning. Twelve year old Frankie walks all over town looking for adventure, observing everything, searching for who she is.

The voice is compelling, and scene by scene there is great momentum, but it is all so intense I kept wanting to step back and catch my breath.

One structurally brilliant element is how Frankie's older brother's wedding, which is Frankie's own emblem for what the story is about, is told in memory and small flashbacks. Frankie is determined t be a part of the wedding and then believes she will be swept up and taken along on the honeymoon. We all know this is painful fantasy, but after long, slow almost natural-time scenes, and instead of dramatizing the crash, we are suddenly on the bus back from the wedding getting brief snippets of what happened, then Frankie's despair, followed by a summary of time passing: the shocking loss of an important character, the breaking up of the house and the world of the first three quarters of the book.

It's as if the great green belly of storm has gathered, but we somehow missed the rain, and we're left with the aftermath of puddles and broken branches. Bernice finally decides to get married, a minor character goes to jail, Frankie gets a superficial friend and is suddenly almost normal, at least for a while. McCullers uses summary with admirable skill, and one is left with the sadness and humor and unbearable pain of growing up human.

It's a brilliant book and I wonder why it doesn't come up on recommended lists so often anymore?

Eleanor and Franklin by Joseph Lash

This is one of those books that take me months to get through because I keep taking breaks for science fiction and Victorian novels. I have to take my time with these big nonfiction projects partly because there are so many facts. This one is a huge and well-written study by a great admirer and personal friend of Eleanor Roosevelt.

Actually, Joseph Lash is a pretty interesting individual himself (see him with ER below)–the child of Jewish immigrants, a socialist and student anti-war activist during the nineteen thirties and forties. He was one of the many "youth" ER befriended, and they became real friends, and he wrote this Pulitzer prize winning book about her and Franklin (but Eleanor is definitely the protagonist). There's another volume about ER alone.

Eleanor and Franklin is a solid book that opened me up to issues and events and people from a few decades before my birth. I have always been a little bored, to be honest, with World War II and Saint Eleanor Roosevelt. What was happening on the ground-- the Holocaust, the killing fields of eastern Europe, the bombing of Britain--all of that certainly was of deep interest to me, but the flag waving American side of it seemed old-fashioned and probably largely propaganda.

This book opens all that up in wonderful ways. It has more than 700 large pages plus extensive notes and other end material. I expect to go back to it as a reference (I bought an inexpensive hardcover via Bookfinder .) I loved the eye-opening survey of ER's upper class upbringing--FDR's too--in the early 1900's and teens. The First World War is prominent in the early part of the book with its shocking carnage for that generation.. It had a huge influence on the people who were in charge during the Second World War. ER came out of her repressed and often unhappy girlhood to work for, and believe in the possibility of, World Peace. Seeing the development of this great American of the twentieth century is at the very least inspiring. FDR was bred to be a leader, but ER taught herself.

She wrote lots of letters, and later journalism, so her internal life or at least her voices, are somewhat available. Even in private correspondence, though, she is always outward-oriented. FDR is seen from more of a

distance (yes, he was a public man, but also he was not Joseph Lash's personal friend). He's the quintessential extrovert, the lover of ships and sailing, the under secretary of the navy, the only son of a powerful socialite mother who was also the frequent oppressor of daughter-in-law ER. FDR's charm, his instincts for how to make change from within, for how to find people to do the work he needed done, are all on display, as is the great challenge of his paralysis after an adult bout with polio.

Finally, I loved learning some of the vast amounts I didn't know--that there was extensive civil rights organizing during and before the second world war; the political organizing of leftist young people; how long it took ER to gather the sophistication to accept the equality of people unlike her–black, Jewish, etc. I regret how much interesting history I ignored when I was a young adult as old fashioned, not radical enough.

Then of, course, there's the marriage. There are some old black and white snapshots of ER taken by FDR in which she is lovely and unselfconscious, and you feel for just a moment what attracted him, aside from her closeness to her Uncle Teddy. Lash is circumspect, but it is clear that it wasn't an easy marriage. FDR in his charming way used ER to take left wing positions and save him the flak. He philandered and flirted.

Lash treats it as a love story (that ER never stopped loving FDR in spite of everything). It gives a nice trajectory to this double biography, but I'm more interested in ER's self-discovery and expansion into one of the great forces of the twentieth century.

Wives and Daughters by Elizabeth Gaskell

It's been a while since I read or reread Gaskell, who is one of the great Victorian realists. She represents the best of the conventional but generous-minded in Victorian writers. This was her last book, unfinished– she seems to have died suddenly as it was coming out in the Cornhill Magazine. There really are only one or two chapters she didn't get to, and you can see clearly that the right young people are going to be married to each other. But you know that from about page 5. It isn't a mystery, it's

a Victorian novel.

The big thing with Gaskell as opposed to, say, Trollope, is that she sees with a calm bright sunlight all the characters and with very few exceptions forgives everyone. She has one almost- villain, Preston, and even he acts, she suggests, not out of viciousness, but out of twisted love. I was, at any rate, happy to be in her world, which strikes me as closer to the real world than what many of the Old Vics gave us,. Not closer than George Eliot, but certainly closer than Dickens. I'm not trying to say she's better than Dickens, but only to say the arena where she was so successful.

I am struck again by how hard it must must have been to be a woman in the 1800's, including physically. My joints ache from merely reading how long they sat and how they stayed indoors at the sight of a cloud, how they are trammeled by their clothes and their rules. Even a small cold leads to days if not weeks of lying on couches out of the draft.

The main character is Molly Gibson. Her widowed father is the local doctor, much loved and handsome, but also a domestic tyrant (and a casual racist who really doesn't care much for women except for Molly). I can't quite tell if Gaskell herself recognizes he's a tyrant: he's a caring doctor and determined in all cases to do the right thing, but in the Old Vic masculine way of doing it by making all the decisions himself.

Molly is eighteen and nineteen and maybe 20 in this novel and supposed to take absolutely no actions not approved by papa and mama, mama being the comic, irritating, and quintessentially shallow Mrs.. Kirkpatrick now Mrs. Gibson.

The best character is probably Mrs. Kirkpatrick-Gibson's blood daughter Cynthia, who has a great deal of self knowledge and admits her selfishness. She jilts two and marries one over the months of this story. And yet she and Molly genuinely love each other. Female friendship is one of Gaskell's particularly good subjects, and she shows it with its ups and downs and loyalty through loss of faith.

There is in fact a whole town full of delightful characters who always rise above their type (Miss Browning and Miss Phoebe Browning; young Lady Harriet and her mama.) The older men are good– Lady Harriet's dad, who's a peer who most of all loves hospitality. Then there's Squire Hamley whose bad temper, family pride (Anglo Saxon, none of these merely two hundred year old peerages!), his prejudices and unbridled tongue cause harm to everyone who loves him.

Softer and lighter than, say, George Eliot, Gaskell patterned herself on Jane Austen, but her stories have a lot of social breadth too. They also have a lot of death–realistically in their time– and she takes on, especially in books like Mary Barton, North and South and Ruth a lot of social ills which were considered coarse for a lady.

Ruth by Elizabeth Gaskell

I read Ruth next, the Gaskell novel that seems to have had the least staying power, and I'm pretty sure when I read it years and years ago I didn't like it a lot--and also totally didn't remember it.

This time, I was prepared for didactic and sentimental, and for the fact that Mrs. Gaskell pretends that women don't have sexual feelings. I also read it this time just weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, when the liberation of women has suddenly seemed much more fragile.

So this time I liked Ruth. You have to accept that it was published in 1853, and that it intends to demonstrate the development and redemption (religiously and socially) of a "fallen" woman. The woman in question, of course, is a homeless, friendless, sixteen year old orphan. Ultimately, Ruth not only turns away from her unfortunate worship of the man who seduced her, she ends as a hero, a nurse who saves many during a time of cholera. This social redemption, along with the so-called coarseness of the subject matter is what made many pan the book when it was published. Friends of Mrs. G. were said to have destroyed the book after reading it.

For today, probably the hardest things to accept are the endemic Victorian sentimentalism and worship of purity and innocence--plus how it ignores female sexuality. In fact, no one is very sexual except the irredeemably selfish seducer himself. Ruth is loving and devoted to him, but it seems to be about having any kind of affection, certainly not physical love. Later, she is determined to understand her transgression, after having discovered the passionate cult of motherhood. Thus a lot of what makes up this novel is things twenty-first century people tend to make fun of, underrate, denigrate.

On the other hand, like other of Gaskell's women, Ruth has a full, rich interior life that confronts her own ethical and spiritual dilemmas. A lot of her contemporaries didn't like reading about a fallen woman's interior life, even a conventional one of Christian redemption, and to make her actions heroic. George Eliot, however, respected it.

The other thing I always enjoy about Gaskell's novels is how complex she makes all the secondary characters, women and men alike, of all social classes. Sally the servant to the Dissident family that takes in Ruth is a comic character (constantly reminding the world that she is not a low church dissident, but "churchwoman" of the Church of England). Her speech patterns are presented as amusing, but she is also a power in the household and quite intelligent in her financial arrangements as well as her human interactions.

Ruth's friend Jemima, daughter of the insufferable businessman and congregant Mr. Bradshaw, has moral battles in herself too: she pushes away the man she loves, then is jealous when he is attracted to Ruth. Then she discovers Ruth's secret and hates Ruth, but also watches her for signs of sin rather than reporting her (or just fainting away for a while). In the end, she is convinced against all her training of Ruth's essential goodness.

Mr. Benson the hunchback minister who is almost painfully too kind and forbearing, yet lives a lie (Ruth's real status) and suffers for it. A lot of these ethical dilemmas are perhaps small and old-fashioned, so I doubt the book will ever be popular now, but Gaskell's characters change and grow so much and so believably. Dissatisfying to me (but you knew it was coming!) is that Ruth's heroic nursing ends as it does.

Even Mrs. Gaskell's version of Christianity (her husband was a Unitarian minister) has more than a few redeeming characteristics!

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Highly and widely praised (see a review from NPR ), this is a book that I definitely get at some level, certainly wanted to keep reading. I was disturbed by the self-destructive main character, and I felt jerked around. Yes, I believe bullied but cool Marianne could become a sexual masochist, but I felt it as a literary decision, as the author making a move, if that

makes sense. I found myself not trusting Rooney to find her natural ending.

What we have here is essentially a coming of age love story covering four years in the lives of two young people from northwestern Ireland, one deeply neurotic and abused but affluent and capable of standing aside from the usual teenage school machinations; one the child of a single working poor mother (she works for Marianne's family).

Marianne and Connell have a complex on and off relationship, and most of it is interesting and complex. They switch positions. They both end up in Dublin, and he becomes the one who is awkward and lonely without friends, and then they switch off, and break off, and come together again, as lovers do. Novels about the intensity of a twosome has never been my cup of tea: I tend to like worlds that open up, social relations, big casts of characters. My favorite parts of this one are the social parts: their secondary school, the college world and insights into and discussions about class.. Love stories that stay focused on the relationship get claustrophobic for me in the end--again, this is probably my limitation, or taste.

Oh, and the ending is not as I feared, a double suicide, but that Connell gets invited to an MFA program in New York City--he's going to be a writer! Oh dear. Is this really Sally Rooney's emblem of a successful life? It seems so naively optimistic, and, frankly, as arbitrary as a double-suicide would have been.

Rooney is far too sophisticated and smart to let this happen without caveats and irony, but still, it's where the novel ends: Marianne unselfishly encouraging Connell to accept the invitation even though she thinks she's giving him up by doing it. This could be just one more swing of their pendulum, of course, and I'm sure Rooney intends multiple possibilities, but maybe she just ran out of ideas or got tired of the characters.

Endings have been tough ever since the end of the Victorian period. Weddings don't do as finales anymore.

Jane and Prudence by Barbara Pym

And more from the British Isles!

I have really odd reactions to Pym's work: It is fun in small does, but I liked this one I liked less than my first Pym, A Glass of Blessings. Jane and Prudence is all Jane the

vicar's wife and her "strange" quoting of poetry and almost entirely aesthetic reaction to religion. She's likable, barely capable of boiling water, pretty sure she's be bad at being a vicar's wife. There are a lot of conscious reminders of Trollope's Barchester and a lot of other familiar Old Vics.

Prudence is Jane's slightly younger friend who lives in London and collects lovers or loves. So the plot, such as it is, is about a widower in Jane's country village named Fabian with beautiful hair (yes, I remember the fifties American singer and Fabio the model for novel covers--does Pym?) and whether he is suitable for Prudence.

Meanwhile, Prudence gets asked out by her boss, is also dating a co-worker, and has some interest shown in her by the local MP.

It's fun by the end, once you know everyone, but meanwhile there is a lot of tea poured and busy bodies reporting what they observe and surmise (likable Jane is one of them) plus a lot of conversation about what men want, and how women waste their time catering to them. I'd like to think the main point is all the female energy wasted on pleasing and manipulating men, but I'm not sure that's true.

Family Furnishings by Alice Munro

Alice Munro doesn't need my praise–she won the freaking Nobel Prize!– but her stories are stunning, and for writers they are an ongoing education in how to do it.

I had read several of the stories in this collection before, but a couple I have to mention, both of them a sort of realistic horror story, were "Runaway" about the dysfunctional if not emotional abusive marriage of a young couple with a horse riding business and the amazing, terrifying "Dimension."

A surprising number of Munro's stories are available free online if you haven't become a fan yet. See Lit hub's list here.

FANTASY, CRIME, & SCIENCE FICTION

The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin

I was disappointed with this. I really like N.K. Jemisin's science fiction, and I know she's setting up a series here, but it took me half the book to be genuinely involved.

Jemi

sin is such a superior writer of science fiction that I gave her book a long trial, and I don't know if it was really worthwhile, but it did get better. I suppose an urban fantasy of this type needs an illusion of current technology, youth fads, slang etc., but these things all felt to me a little strained.

At the same time, it is consistently witty, and I liked a lot of the aspects of the characters, especially sassy Bronca the Bronx and Brooklyn. The Enemy is nicely imagined with this burgeoning of nasty white towers and fronds and tentacles spreading over everything.

I was also a little disgruntled over the obviousness of the Borough of Staten Island, who was this whiney little whitegirl with a wildly stereotyped cop-father (I mean, the Staten Islander I know best personally is a feisty Irish-Italian intensive care nurse who was the oldest of seven kids in a working class family, and she's politically liberal and big sister-bossy in all the best ways) - but Jemisin was looking for stereotypes for her avatars, I guess.

Anyhow, I suspect "Aislyn" will get another chance to rejoin the City. I hope. I mean, if you really want diversity, shouldn't you include cisgender whitegirls too??

There's a lot of fun, eventually, but in the end, I went and ordered a more traditional Jemisin Science fiction series--and also went back to reread one of Octavia Butler's really good ones....

Dawn by Octavia Butler

Dawn (1987) is the first of the Lilith's Brood trilogy (the series was originally called Xenogenesis). The others are Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989). It's a reread for me, but still so excellent: everything I want in science fiction: a brilliant idea (what if our human DNA could be mixed with an alien species' DNA?); a strong main character, Lilith; and sympathetic but flawed aliens with a complicated sex life and reproductive strategy. If any faults, and I'm not sure it does, it is the slight speed up in the second half. I was ready to meet tons of new human characters to be brought out of suspended animation, but Butler gets on with the story. This may be in the end what makes it genre rather than literary? That character development and even world building are subsidiary to story? Thus probably the fatal flaw in my science fiction novels The City Built of Starships and Soledad in the Desert?

The Killing Moon by N.K. Jemisin

And back to Jemisin, and, whee! I still love her work!

This two book series, the "Dreamblood" novels, is so much better to my taste than the urban diversity apocalypse with the snappy repartee. The Killing Moon is a vaguely ancient Egypt-inspired fantasy that centers on a a religion that worships a sleeping moon goddess (and there is apparently, rather subtly slipped in, a second moon, the "Waking Moon.") The priests of the religion work with dreams, take them in from dying people, then help the dying in their passage (or just sometimes just assassinate them, even though they'd rather not). The harvested dreams are shared with other priests who use them for healing. The fantasy is mostly centered around this, but there's a lot of politics and secrets and nicely slipped in mythology.

What I love here is Jemisin's subtlety and her super splendid world building.

I'm eager to go back.

Dark Sacred Night and The Night Fire by Michael Connelly

We're getting close to the present time now in our reread of the Harry Bosch books. Connelly has always used current events and technologies very well: Bosch's slow adoption of computers and his honoring

of old school police detection are believable and charming.

Dark Sacred Night splits the point of view between Bosch and Renee Ballard, an LAPD detective in trouble for calling out a superior officer for sexual harassment. She is a loner, often sleeping after her night shift in a tent on the beach guarded by her dog. She then gets up and surfs, always with the memory of her single-father who once left her on a beach and never came back. It's a decent thumbnail backstory, not as good as Bosch's, and, of course, she's not as good as Bosch either, although a book with the two of them works well enough. The plot has a couple of good cold cases going at once--another predator serial killer, some gangbangers with a hit out on Bosch, etc.

Finally, The Night Fire also scratched my itch for Los Angeles noir, cold cases, a good villain, and Bosch. Renee Ballard is still splitting point of view with Harry, but in a book like this that has Harry too, it's okay. Ballard does the LAPD stuff, he works with her and continues to investigate for his half brother, the Lincoln Lawyer.

THINGS TO READ ONLINE

Nikolas Kosoff's story about a boy with a unique world view is available online at "Evolution." The boy's world view--and his world-- are very interesting. It's a gripping story of school life, New York City, making friends--and seeing, if not solving, a mystery.

Two lovely poems by Dreama Frisk are online at bourgeononline. She says " I do love one of the poems, 'My Orange Bathing Suit' which I edited and it finally said what I had in mind all the time. I had no idea about editing poems. I thought they were just born."

Diane Simmons' "The Big Time" in Hippocampus Magazine.

Check out Harvey Robins on how New York City could return to putting the needs of the public over the needs of corporations (for-profit and non-profit both ) in public spending.

Kelly Watt has a flash fiction online at Microlit Almanac. Also take a look a her book blog.

New issue of The Maryland Review is up!

The Jewish Literary Journal had published a new issue for over 9 years~ See the latest issue here.

Nancy Solomon, who covers New Jersey for NPR, has a new podcast about the deaths of a New Jersey power couple: Dead End: A New Jersey Political Murder Mystery.

Suzanne McConnell reads a short short about Arkansas and much more.

What to read instead of J.D. Vance's book Hillbilly Elegy.

A piece by Ed Davis at Journal of Practical Writing on publishing a story after ten years and forty submissions.

Latest issue of Authors Publish with places to submit and a lot more.

A substack blog with lots of information, out of Pittsburgh: Littsburgh.

Everyone needs to edit their work. Here are some specific examples of editing from Danny Williams: "Real Life Adventures in Editing."

ESPECIALLY FOR WRITERS

Check out the NY Times on the growing importance of TikTok to book publishing. Note that the writer they feature is the excellent novelist of ancient history and myth, Madeline Miller, whose Circe we reviewed in this newsletter.

Danny Williams on how to choose, edit, and when to use proper names in your fiction. And, FYI, Danny's editing store is open--write Danny Williams at editorwv@hotmail.com .

Philip Klay on how to write about war.

Jordan Kisner inThe Atlantic on failing to cross cultural divides in fiction (review of Geraldine Brooks's Horse).

Alice Munro's stories are a how-to-write course, and a surprising number are available free online. See the Lit Hub list here.

Digitalize your work! I don't usually recommend commercial ventures, but I and others have been using Golden Images for at least fifteen years. They do various kinds of conversions to digital (a printed book to, say,Word files for editing). I recommend these folks, and I also recommend that anyone who doesn't have their work in digital form somewhere to have it done as soon as possible!

See their website at Pdfdocument; email them; call 666-375-9999.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Coming in November 2022 from WVU Press: Rachel King's "Bratwurst Heaven!"

Molly Gilman is officially an audiobook narrator! She did A Blueberry Moon for Corah, published and availablefor purchase on Audible. It will be on Amazon and iTunes soon. All links are on mollygilman.

Pamela Erens has a new book--and lots of chances to see her speak about it: Middlemarch and IThe Imperfect Life. It's part of Ig Publishing's Bookmarked series, in which authors write about a favorite work of literature. Each volume is an idiosyncratic mixture of personal essay, literary appreciation, and craft talk. An excerpt of the book will be published on Literary Hub.

Leora Skolkin-Smith's new novel Stealing Faith is due out in August, 2022!

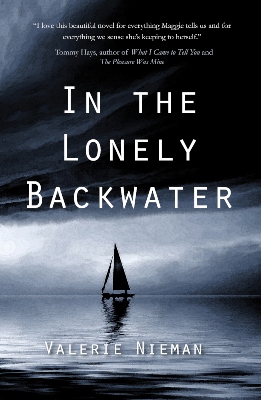

Valerie Nieman's In the Lonely Backwater

Meredith Sue Willis's

Books for Readers # 223

September 17, 2022

This Newsletter Looks Best. and its links work better, in its Permanent Location.

Back Issues MSW Home About Meredith Sue Willis Contact

Announcements

Lists

Reviews

Read/Watch/Listen Online

Notes on What We Read (George Lies & Donna Meredith)

Especially for Writers

Fantasy, Crime, and Science Fiction

Irene Weinberger Books

Irene Weinberger Books has just published a New Edition of

Meredith Sue Willis's novel Love Palace!

Buy it from Bookshop.org or any of the usual online hardcopy suspects.

Also available as a Kindle book on Amazon, and for most e-reader formats at Smashwords.com.

If you buy the e-book from Smashwords, use code VF64S at checkout to buy for only $1.00!

REVIEWS

This list is alphabetical by author (not reviewer)

Fascism: a Warning by Madeleine Albright Reviewed by Joe Chuman

Children of Dust by Marlin Barton reviewed by Rhonda Browning White

The Long Good Bye and The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke

and Auguste Rodin by Rachel CorbettThe Boston Girl by Anita Diamant

The Dancer from the Dance by Andrew Holleran

The Shadowed Sun by N.K. Jemisin

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

The Lola Quartet by Emily St. John Mandel

African History: A Very Short Introduction by John Parker and Richard Rathbone

Election by Tom Perrotta

Auguste Rodin by Rainer Maria Rilke

Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

Butcher's Crossing by John Williams

Some Thoughts About Updating a Novel

Summer reading for me generally means meandering down roads with authors I missed the first time round. I have found I am pretty much ready to read anything by Emily St. John Mandel; ditto N.K. Jemisin. I Also this summer read a couple of books inspired by a visit to the Rodin exhibit at the Clark Museum in Williamstown, MA, and I also picked up one of the Oxford "Very Short Introductions," this one on the continent of Africa. Also in this issue are reviews by Joe Chuman and Rhonda Browning White, plus some remarks about personal reading habits by George Lies and Donna Meredith.

I also want to announce that I have just prepared and updated my novel Love Palace both in hard copy and as an e-book. I was inspired to do this after some discussions in my novel writing class about how to write a

contemporary novel. It is obvious that some novels (and of course movies) speak to certain age cohorts and capture the essence of a moment in time. When it happens naturally--when someone seems to speak for a generation or a group-- there is often a confluence of art and financial success. Such books occasionally are equally meaningful to later generations, but equally often they lose their allure. Mainly, I don't think anyone can set out to write them--I think they just come.

Almost all other novels are, In my opinion, either created world novels or historical novels. That is, writers have to do world building whether we are carefully constructing a post-apocalyptic landscape or a sword and sorcery fantasy, or if we are writing about 2022. It's one of the things that I love most about novels: that they take me to other times and places. Either in the foreground or the background are always certain technologies and styles of clothing and manners and commonly accepted beliefs. Badly written novels assume we already know most of this and agree about it rather than creating specific experiences and worlds.

I remember a "contemporary" novel from fifteen years or so ago in which the protagonist makes a living writing a blog. He travels around having adventures and occasionally filing stories electronically. It's the fantasy of an exciting reporter's life that just happens to be digital. But in the real world, making a living as a journalist has been deeply disrupted by digital technology. There has been no simple substitution of digital content for printed news. The world of social media has opened up, destroying and creating, more than we can even imagine at this moment. The writer of that blogger story had no idea of the coming of TikTok. My point here is not that a novelist shouldn't use blogs or TikTok or Youtube, but that they need to present those things as of their time. One solution is to offer a frankly alternative world, in which, say, personal computers never happened. Generally, though a story set in 1960 or 1949 or 2022 needs to be grounded in its time. The novel that assumed blogs were just the same as snail mailed or called in stories just felt dated and mistaken.

Likewise, a dear and now departed friend in my writers group, who was born around 1920, found one of her old stories that took place in showrooms of the garment industry in New York City in the early nineteen-fifties. The company in the story specialized in young girls' "frocks," and the main characters were two exquisitely dressed aging female sales representatives who try to sell the clothes to buyers who come to the show room. The women in the story are wonderful characters, and the place beautifully embodies a particular culture at a particular moment in time. My friend wanted to polish up her rediscovered story and publish it, and we in her writing group supported her fully, but insisted that she keep it in the nineteen fifties. No, she insisted, she didn't want it to have a date; she wanted it to be "timeless" and "universal." She refused to admit that the strength of the story was indeed in its universal qualities, but that its universality grew from its specificity.

This kind of specificity is what I was attempting with my update of Love Palace. In the first few pages, the narrator is in a bar circling possible job opportunities in the classified ads section of a newspaper. A newspaper made out of paper. I wanted her doing this in public so that another character could see her doing it. I knew pretty much exactly when this was happening (in 2005 or 6). When I wrote it, not all that long ago, I never imagined how few people would be circling ads in a paper newspaper today. I wanted simply to make it clear what she was doing, and that it was normal at that moment in time.

I also had a little idea I liked in which the narrator and her mother are in the youngest and oldest cohorts of the Baby Boomers. Neither the Baby Boomers nor the newspaper classified ads were essential to my story, but I liked both things. I could have cut them, but decided instead to adjust and clarify some dates to clarify that the story was taking place in 2006.

That year was just before Barack Obama's successful run for president. It was the year the iPhone was introduced but had not by any means replace flip phones. I added a few more details and made minor corrections to my time sequence. I looked for assumptions that people made then but not now, and thought about things such as how were community organizers regarded in public consciousness? Obama had been one--was it cool to do community organizing in 2006 and 2007? Maybe not so much for a reader in the 2020's? My changes to this novel were really very small, just a kind of cleaning up after the party.

In the end, Love Palace hasn't changed very much except, I hope, to be a little more aware of itself as historical.

P.S. For writers: more on whether and how to write contemporary novels.

Lincoln Highway by Amor TowlesThis highly praised and popular magical realism novel begins delightful and twisty, all nineteen fifties local color. Emmet Watson is just out of a youth prison/work camp, a true blue straight arrow who killed someone inadvertently in a fight, with big plans for himself and his little brother Billy, a brilliant seven year old who reads and rereads a fictional book called Dr. Abacus Abernathy's Book of Hero Stories.

Billy also turns out to be what I call a Hollywood Innocent, one of the children the movie business sentimentalizes and romanticizes.

The most fun in the book comes from Emmet Watson's co-inmates Duchess and Wooly, who are quirky and dangerous in really interesting ways. The novel has a lot of things that are terrific, especially in the first three quarters. After that, as Towles comes upon his ending, there are probably just too many random ways to finish. The book is largely upbeat, and the good people (Emmet & Billy and their Nebraska mother/wife figure Sally) seem likely to get what they want, as do Dr. Abernathy and a hobo named Ulysses, who is on a quest to regain his wife and son like the "Great Ulysses."

However (plot spoiler coming), the more difficult and complex characters, namely Wooly and Duchess, respectively commit suicide and drown out of greed. These are perfectly legitimate endings for the characters, perhaps especially Wooly, but while Duchess's exit will make a really nice movie scene (underwater, seeing all the people of his life as he sinks), it is a nicely written cop out that disposes of the complex characters and rewards the conventionally innocent and heroic.

It's a lot of fun though: wonderful scenes of riding the rails, in the halls of the Empire State building, at a hobo camp in Harlem, and in a rich folks' camp in the Adirondack as well as an orphanage run by a very clever nun.

For other opinions, see the NPR Review, the New York Times and, for those who might possibly care, Bill Gates.

The Lola Quartet by Emily St. John MandelThe tone here is mildly depressed as various people from South Florida in their mid-thirties live their lives. Their lives include a lot of waking with hangovers, fighting addictions, and being chased by murderous drug dealers.

The characters center around a musical group from high school, and all have had early-mid life crash-and-burns: theft, drugs, a gambling addiction, a newspaper reporter who starts making up quotations for his stories. They all speak with the same rhythms and use interchangeable imagery. Whatever the background or race or personality, they all sound the same. It reminds me of the young people in the private boarding school novels I've read. A lot is being assumed that I don't subscribe to, and that puts me off.

And yet– I think I would read anything Emily St. John Mandel wrote. I can't always say I like all her work, but she is consistently interesting.

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

The Glass Hotel is one I'm very happy I came across. If you want a good summary, this piece in The Atlantic by Ruth Franklin would be a good place to start. What I want to say instead and again is that Mandel knows what she's doing and is always, always interesting, whether she' writing post-apocalyptic fiction like Station Eleven or this multi-plotted multi-charactered novel about a remote hotel and a Bernie Madoff style Ponzi scheme.

The novel has ghosts. The Atlantic writer thinks they are the embodiment of guilty consciences, but it seems to me they are just the lingering presences we see if we have unfinished business. The head of the Ponzi scheme, who spends a good chunk of the novel in prison, sees a lot of the ghosts, many of them victims of his crimes. One major character dies and gives us a tour of what it's like to be a ghost. All of these things are done beautifully.

If I have any complaints, they would be that some of the tying up of plot points seems a little too neat and arbitrary, and also what I said in the review of above of The Lola Quarter, that the characters have a sameness of diction. They are pretty much all likable, or at least understandable, but there is a certain lack of family and ethnic texture. I miss the long past, the ethnic past, that makes a lot of what we are.

But, as I indicated, I've read three of her novels, and I have a hold on the Kindle library version of her latest.

Children of Dust by Marlin Barton Reviewed by Rhonda Browning White

(From Regal House Publishing September 2021 ISBN-13: 978-1-64603-079-8)

Can a white male from Alabama honestly and honorably write about racial injustice, infanticide, and wife abuse and infidelity? Yes—and he can do it incredibly well—if he is Marlin Barton. Southern author Marlin Barton’s most recent novel Children of Dust tells two juxtaposing stories of generations of the same family set over two hundred years apart as they navigate the emotional wounds caused by their forefather.

Rafe Anderson, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War, is the patriarch of this family’s twisted lineage. Rafe fathered fourteen children by three different women: his wife Melinda, a Caucasian woman; his confidant and lover Virginia, a Black woman; and his mistress Betsy, a mix-raced woman who is the daughter of Annie Mae, the Anderson family’s half-Black-half-Choctaw midwife and housekeeper. When Melinda’s tenth child is born healthy yet dies only hours after birth under suspiciously gruesome circumstances, Melinda, Rafe, and Annie Mae point fingers as mistrust irreparably shatters this already fractured family. Rafe’s love affairs and children with two women of color is hypocritically compounded, because following the war he led the slaughter of dozens of black slaves.

Centuries later, two of Rafe’s descendants, one Black, one White, meet on uncomfortable terms to compare their ancestry, their vastly different upbringings, and what their present and future hold as children of Rafe’s troubled and violent bloodline. As the two men Seth and Charles cautiously reveal and contrast what they know of their family history, they discover Rafe’s war-damaged psyche and how his violent actions and the memories thereof carried that harm to and into those who he tried to love, finally realizing they have more in common than shared blood.

Children of Dust is not a diatribe or primer on learning from past mistakes; rather, it’s a fictional account of historical truths laid bare, without moral commentary. Barton simply relates to us here is what these people did, how they felt, and what happened to them: What do you think?

This is not a comfortable read. Yet, for all its psychological and physical violence, the story is infused with tenderness and, ultimately, understanding, and that is the lesson we might learn from this novel.

African History: A Very Short Introduction by John Parker and Richard Rathbone.

This is one of the Oxford "Very Short Introductions," of which I especially enjoyed the ones on the Big Religions. This one was less gripping, but helpful in clarifying a few things for me. The authors spend a lot of time on the challenges of historiography, especially because of the lack of a written record from ancient times in Sub Saharan Africa. In Africa too, much of the history was written by citizens of the the colonial powers, and the authors are themselves white and British. I wonder how the book would have been different written by someone black, and if black, whether someone of the black diaspora versus an African.

Parker and Rathbone are old fashioned in a lot of ways, but seem to try pretty hard to be even-handled with what little they have space for. One thing that was very striking was the fact that (why didn't this ever occur to me?) the colonial period in Africa lasted less than a hundred years: from the 1880-90s through World War I. After World War II was a period of nationalism and rejection of the imperial powers. So in spite of all its importance, colonialism was a blip in African history.

Another interesting section talked about the "kings" in the 1500's through 1807 who profited hugely from slave trade. Generally, European slavers were kept out of interior Africa and dealt with by black representatives of the kings.

Also of special interest was a comparison of Muslim invaders and influence in north and east Africa to Christian invaders in West and South Africa. I'm glad to have read it, and I'll go back to the little volume.

Auguste Rodin by Rainer Maria Rilke

This is a tiny book with 1903 photos of some of Rodin's work.

It is Rilke's famous monograph on Rodin that tries to capture the sculpture in words. It is stirring and convincing as one person's tour of the sculpture of someone he considers a great artist from whom poets can learn as well as visual artist. It has an interesting prologue that discusses Jessica Lemont, the young woman who translated it and gave lectures on Rilke for Americans.

One cast of Rodin's "The Thinker" was the first piece of serious in-the-round art I ever saw. It was at the Cleveland Museum of Art around 1960. I also have a post card on my desk of the lovers' feet from "The Kiss," and I never go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City without going by the "Burghers of Calais" (detail below).

So I'm a fan, and it was a shock to me some years back when I learned how many casts of how many sizes were done of Rodin's most famous pieces. And, of course, his clay and plaster was cast in bronze or carved in marbles by others.

So Rodin was, finally, both a great artist and a great entrepreneur. My Cleveland Museum of Art Thinker was huge, whereas the original sculpture had been smaller, meant to be the capstone of his "Gates of Hell"--possibly meant to be a portrait of Dante himself.

So if Genius isn't quite what I imagined all those years ago, I'm still moved by Rodin's bodies and faces and feet.

You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin by Rachel Corbett

I wanted more Rilke and Rodin, and found this book. In a 2017 commentary in the Harvard Review , Erik Hage says, "...this critical biography is very much about the creative expansion of the Prague-born Rilke, who was still a struggling poet in his twenties when he came under the spell of French sculptor Auguste Rodin, then a lionized master in his sixties." It's a good review that gives an excellent sense of themes and structure of the book.

I'm going to write here a collection of things that pleased me in it. First there is the wide-ranging view of a moment in time in Europe, mostly Paris–art, the delights of debauchery, the rise of psychoanalysis, and the run up to World War I. It was a time of social life, of artists fertilizing (and sleeping with!) each other. Young Rilke gets a commission to write a monograph (see above) on Rodin and goes to Paris to immerse himself in Rodin's work, to write the piece, and to learn from Rodin how to be an artist. Famously, Rodin rose to the young poet's challenge by saying you have to work all the time: "Travailler, toujours travailler." Eventually, Rilke goes away, comes back to be Rodin's secretary, which starts well and ends disastrously, and finally Rilke's career as a poet and writer takes off.

Rilke has conflicted feelings toward Rodin, but also toward Paris itself, where he eventually gets a cheap apartment in an old mansion in Paris (the Hotêl Biron) that becomes a sort of WestBeth or Chelsea Hotel with Cocteau throwing parties and Isadora Duncan dancing in the garden. Eventually Rodin himself takes rooms, and the building becomes the present Rodin museum.

And the parties. The historically wild parties.

Meanwhile, the end of the book is very sad as Rodin ages. He has a lack of sympathy for new art and artists like Matisse and the Picasso. Rodin rejects the new and visits Gothic cathedrals.

Something else Corbett does very well is the women artists: Clara Westhoff who studied with Rodin, then married and had a child with Rilke. Her friend was Paula Becker, whose sad early death cut off one of the great artists of the period. Then there was the apparently ever fascinating Lou Andreas-Salomé who is a lover and/or mother figure to half of Europe's intelligentsia--and becomes a Freudian analyst.

If you are interested in any of the artists and writers or simply the period, Rachel Corbett lays it all out and guides you through.

The Boston Girl by Anita Diamant

This was a best seller a few years ago, and I enjoyed it. It's not a difficult novel-- not that it isn't serious, but it is direct, told in the voice of a grandmother telling her life to her granddaughter, sharing, encouraging, always in the end upbeat. The narrator Addie Baum is the only member of her immediate family born in the United States: a little brother died shortly after arriving, and her parents and older sisters are all in various ways lifelong greenhorns. Her father lives to go to shul and study; her mother hates even the cabbages in the new world. One of Addie's older sisters is withdrawn and shy; one leaves home to live on her own and work as a shop

girl. Both sisters marry, in sequence, the same man, a good hearted entrepreneur. Addie goes to school and to a settlement house and does well in all her studies. She gets jobs, has unpleasant relationships with men; eventually meets the right one. There is the first world war. There is the deadly Spanish Flu.

Interestingly, Addie, for all her intelligence and ambition only finishes her schooling and finds a calling after she has married and had children of her own.

Without softening any of the evils of urban immigrant life, Diamant draws us into what human happiness can be, maybe the most it can be. She isn’t a subtle writer, but she's a very convincing one. She writes in a major key, perhaps even without the black keys--all of which sounds a little critical, but I read it practically straight through, cheering for Addie and her family all the way.

The Dancer from the Dance by Andrew Holleran

This exquisitely sad 1979 novel has hit the sweet spot for a multitude of readers. It is possibly the classic depiction of the decade and a half between Stonewall and AIDS–a defiant over-the-top testosterone-soaked

world in which gay men attempted to have it all at once. It is the gay world of Manhattan's dance clubs and Fire Island, centered on two characters who embrace and define and go beyond the stereotypes they embrace: Malone is a gentlemanly idol for everyone who knows him with a beautiful body, social graciousness and sheer kindness. He embodies the beauty and desire, and mystery, and spends much of the latter part of the book as a prostitute until his mysterious exit.

Sutherland is a self-identified queen, usually in costume like a founding member of the Village People, but much more exquisitely dressed. He's a party giver, a mentor and a guide through the world he is helping to define. He also provides drugs for every occasion.

The novel itself has what seems to me a totally unnecessary epistolary frame of letters between two friends, the "writer" of the novel and someone who fled the milieu that the novel creates. What is the point? There is also a certain lack of control of the story line, and maybe too much repetition, but this aspect may be what makes it feel so authentic– was that world ever in control? Is my far more conventional world?

For further reading try these online pieces about The Dancer from the Dance: The Guardian; a"deep dive" into the book ; the New York Times in 1979 review

Butcher's Crossing by John Williams

The New York Review of Books classics edition I was reading had an introduction by Michelle Latiolais that included both personal notes on Williams as a teacher and an overview of his books, which were written in various genres. She rates this ostensible Western on a level with the brilliant Cormac McCarthy Blood Meridian.

Butcher's Crossing is also brilliant and beautiful, although for reasons I haven't fully analyzed, I think I'll always admire John Williams' work more than love it. This is a kind of coming of age story with lots of men contemplating the great natural West and then slaughtering thousands of buffalo strictly for their skins. Then they face the real challenge, which is surviving six months of winter in the Rocky mountains when they get snowed in (the trick is--buffalo hides).

The end is bitter or disastrous for the older men. The young protagonist's outcome is less clear, except that he is sure he'll never go home to the comforts of Boston. There's a good hearted whore, also young, who is heading off to better hunting grounds, probably St. Louis. It's bleak and lonely and beautiful and gripping, and it is very clear that Williams sees the subduing of the West as ambiguous at best.

At once super-realistic, and dreamy, but for me at least, the opposite of a cuddly book.

Election by Tom Perrotta

They started shooting the Reese Witherspoon movie of this book before the book was officially published in early 1998. That's a real vote of confidence. I liked the movie pretty well, but the book is far sharper and funnier

and poor Tracy Flick is at least as sad as she is obnoxious. She just tries so hard.

I read this because a friend recommended Perrotta's latest book, Tracy Flick Can't Win, but said I had to read Election first, even if I had seen the movie. So I did.

Election has at least six narrators each speaking in anything from half a page to several pages. The jumping around works quite well as a narrative device as well as character exploration. Each voice tells the next part of the story, and the choice of narrator is always in the service of who's going to have the funniest perspective. I hooted occasionally and snorted often. What a bunch of sad sack losers, from the teacher who loves teaching but has to give it up due to his own foolishness to the popular football player who doesn't really want to run for school president but is so agreeable to everyone that he gets on board plus his little sister who has just discovered she loves girls not boys and wants to transfer to a Catholic school and starts wearing the pleated skirt and knee socks to the public school.

It is light and very funny without being over-the-top or nasty. Wikipedia categorizes it as "black comedy," but it's more sad than dark: a small, multi-voiced novel with a lot of attitude about the human condition.

Especially the destructive power of sex.

Fascism: a Warning by Madeleine Albright Reviewed by Joe Chuman

As an avid obituary reader, I perused with interest the article in the New York Times on the life of former Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, who died on March 23rd at the age of 84.

I came away from the review of Albright's life and accomplishments with the impression that she was a person of prodigious substance and ability. Madeleine Albright was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937, a place and time rich in history. In addition to English, she spoke Czech, Polish, French, and Russian. Madeleine Albright held a doctorate in international affairs from Columbia University, having studied under Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter's national security adviser. She taught at Georgetown and was a director of the Council of Foreign Relations.

Albright was arguably born into a career on the international scene. Her father, Josef Korbel, was a high-ranking Czech diplomat and, having emigrated to the United States, became a professor of international

politics at the University of Denver, where he served as a mentor to Condoleezza Rice. Born just before World War II, Albright fled with her family to England, returned to Czechoslovakia, and fled again when their homeland fell to Communism, before coming to America.

One surveys Albright's life story with the impression that she was not only keenly intelligent, but also highly educated in academia, as well as by personal experience drenched in historical events. Albright was a model of independence and accomplishment and did not have to expound feminist ideology to admirably exemplify a strong, self-confident, and independent woman.

Albright authored five books. Fascism: A Warning, published in 2018, is the last. Clearly, the election of Donald Trump was an inspiration for writing the book. But while strongly supporting Hillary Clinton's presidential bid, she asserted that she would have written the book anyway had Donald Trump not become president, wanting to lend momentum to democracy during the first term of a Clinton presidency. Yet she states, nevertheless, that Trump's victory gave her a sense of urgency.

In my view, the most striking aspect of the former secretary of state writing a book warning of the dangers of Fascism is the fact that she chose to write it. As such, it takes its place among a long list of volumes sounding the alarm about the emergence of Fascism, the demise of democracy, and the rise of authoritarianism in the current moment.

While citing urgency as a motive for writing the book, I scanned the pages with the sense that her warning is not urgent enough. The text suffers from a lack of tight organization and the voice of the author often sounds desultory and diffuse. Fascism is part history, weak on theory, while sprinkled with interesting tidbits from Albright's biography. But the urgency is lost in a tone of academic distance, and to a great extent is lacking in academic or theoretical rigor.

For example, even Albright's definition of Fascism seems overly broad and somewhat vague. It is an extreme form of authoritarianism to be sure, but it is not clear what conceptually defines it. Noting that there can be Fascism emanating from the political left as well as the right, the closest she comes is as follows:

“...Fascism should be viewed less as a political ideology than as a means for seizing and holding power.”

“Fascism...is an extreme form of authoritarian rule. Citizens are required to do exactly what leaders say they must do, nothing more, nothing less. The doctrine is linked to rabid nationalism. It also turns the traditional social contract upside down. Instead of citizens giving power to the state in exchange for protection of their rights, power begins with the leader, and the people have no rights. Under Fascism, the mission of citizens is to serve; the government's job is to rule.”

Or, “I am drawn again to my conclusion that a Fascist is someone who claims to speak for a whole nation or group, is utterly unconcerned with the rights of others, and is willing to use violence and whatever other means are necessary to achieve the goals he or she might have.”

True enough. Fascism is a species of authoritarianism, but it is not clear from Albright's rendition what makes Fascism distinctive as a manifestation of authoritarianism.

This wide interpretation opens the door to a survey of history's bad actors, but how they are ideologically similar beyond a yen for power and dismissal of democratic norms is not clear. Within her study, she places in the same tent Mussolini and Hitler, but also Joseph McCarthy and such contemporary figures as Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, Roberto Duterte of the Philippines as well as Kim Jong-il, and the contemporary Korean ruler Kim Jong-On. While Mussolini and Hitler are the prototypical Fascists, and we can readily place the Kims with them, is it theoretically coherent to locate Joseph McCarthy in the same camp as Chavez and Duterte? They are all tyrannical and power-hungry. But Fascism relates to a political system that goes beyond personalities.

Albright's thesis would most helpful if she could clarify the common political, social, and economic conditions that enable Fascist leaders to assume the helms of state. Assuredly in reviewing the historical accession to power of each of her protagonists, she discusses the context of their emergence. But systemic similarities are not sufficiently clear by which to draw confident lessons that can pertain to the current moment.

What seems broadly true is that Fascist leadership fills a vacuum created by political and economic instability. So it was with Benito Mussolini, the archetypal Fascist, who organized his own squads of armed men to wrest power from a Socialist parliament with the help of Italy's powerless king, Viktor Emmanuel. Hitler and Nazism arose out of the losses and humiliation following the German defeat in the First World War. As Albright notes:

“...the silencing of guns had been accompanied by the dishonor of surrender and so, also, the victors' demand for blood money, the loss of territory, and the dissolution of the territorial regime. To Hitler and many other soldiers, this startling and humiliating outcome was not something they could accept. The war had reduced the ranks of German men between the ages of nineteen and twenty-two by a number of 35 percent. The fighting and economic deprivation had pulverized the nation. In the minds of enraged survivors, the cause of their disgrace had nothing to do with events on the battlefield: Germany had been betrayed, they told themselves, by a treasonous cabal of greedy bureaucrats, Bolsheviks, bankers and Jews.”

"After a series of elections in which the Nazis failed to win a majority, but fearing the communists, the aging president, Paul von Hindenburg gave the keys of power to Hitler, as Viktor Emmanuel did with Mussolini a decade earlier. As Albright notes, Hitler and the Nazis went on to amass power via a political blitzkrieg, destroying what remained of German democracy. This he did by sending out thugs to brutalize opponents and sending them off to newly formed concentration camps, taking over the unions, banning Jews from the professions, barring unsympathetic journalists, and consolidating police functions under a new organization, the Gestapo.”

It is important to know, as Albright reminds us, that Nazism had its allies in the United States. Fritz Kuhn, a chemical engineer and German immigrant,organized the German American Bund in 1936, which championed a Nazi victory in Europe. Its high water mark was a rally at Madison Square Garden in February 1939. Twenty thousand attended to shouts of “Seig Heil” while Kuhn mocked FDR as President Frank D. “Rosenfeld” and his “Jew Deal.”

Albright includes a chapter on Stalin. While Fascism and Communism viewed the other as enemies, and each augmented its legitimacy through calumniating the other, Albright's definition of Fascism is sufficiently broad to include Communism within its fold. While delineating their marked differences – Nazism was obsessed with race and nationality and Communism with class – both consolidated power in the state, sought to shape the minds of citizens through relentless propaganda, and employed violence and murder at monumental scales. Both were utopian schemes that sought to create “a new man.” This is sufficient to identify Communism as a species of Fascism. Despite discussing Stalin at length, for reasons unexplained, Albright does not include a word about Mao, who one might conclude fits into the same broad political parameters as other major purveyors of violent tyranny.

Nothing here is new and one can ask whether an understanding of history is best served by so closely bringing Nazism and Communism together under the rubric of Fascism.

Albright's treatise is most valuable when discussing more recent figures who are shaping our contemporary political landscape. There is a chapter devoted to Putin, but I found the sections on Recep Erdogan of Turkey and Viktor Orban of Hungry to be most instructive. Erdogan's assault on Ataturk's secular legacy, his increasing Islamicization of Turkish society, which has resulted in the condemning of the LGBT community, and sending women back to traditional roles as mothers and into the home, holds out little promise of a democratic future for Turkey.

Viktor Orban's Hungary represents the autocratic state of greatest consequence to the United States in that Orban's “illiberal democracy” is a projected bellwether for the type of government that the Trumpist camp would like to see America become. Orban has hollowed out the Hungarian parliament. He has made the judiciary subservient to the executive and he has roped in journalists who are critical of the regime. He is also championing Hungary as a Christian society while barring immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. He attacks the European Union, a common trope of right-wing nationalists. And he is not beyond conspiracy-mongering, using George Soros as a scapegoat, and making moves toward anti-Semitism. One finds a direct line to Trump's proto-Fascism, and, as mentioned, Orban has become a darling of ultra-conservatives and Trump's acolytes in the United States.

Trump bookends Albright's thesis. In many ways, Albright gets it right. She is on target in asserting that Trump is a demagogue. She points to his mendacity, his undermining of democratic institutions, his railing at “fake news,” his attacks on the FBI, and his claims of rigged elections.

It is no surprise that Albright extends much of her critique to Trump's foreign relations. She critically notes the renunciation of the Paris climate agreement, his badmouthing of the Iranian nuclear deal, squandering resources on the Mexico wall, and other destructive acts of folly.

But she is most concerned with the diminution of America's standing in the world, especially in the eyes of our allies. She notes:

“... the presidency has been painful to watch. I find it shocking to cross the Atlantic and hear America described as a threat to democratic institutions and values. A month after Trump's inauguration, the head of the European Council listed four dangers to the EU: Russia, terrorism, China, and the United States. In the wake of one Trump visit, an exasperated Angela Merkel said, 'The times in which we can fully count on others are somewhat over.' Since early 2017, surveys show a marked decline in respect for the United States.”

She rightly points to Trump's “America First” foreign policy, noting how this recapitulates the 1940 America First Committee that brought together Nazi sympathizers to try to halt the nation's entry into World War II. Albright states that the America First Committee claimed 800,000 members and had the active support of Charles Lindbergh, who made anti-Semitic allegations of Jewish influence pushing the United States into conflict.

Albright appropriately concludes that Donald Trump is setting the stage for Fascism, and she is rightly worried. She ends her book by saying,

“Some may view this book and its title as alarmist. Good. We should be awake to the assault on democratic values. That has gathered strength in many countries abroad and that is dividing America at home. The temptation is powerful to close our eyes and wait for the worst to pass, but history tells us that for freedom to survive it must be defended, and if lies are to stop, they must be exposed.”

This is assuredly true, and Madeleine Albright's admonitions are essential. Yet I leave her text having wanted more. Her tone is reminiscent of mainline news reporting early in Trump's term. Then Trump was seen through the lens of a political actor whose policies were worthy of rational critique. Missing then, and missing in Albright's treatise, is a strident and militant assertion of how Trump is not merely a political actor with an extreme agenda. He is a malignant narcissist and sociopath, whose policies are outside the domain of rational or normative assessment. Lacking also in her critique is an appreciation of Trump's penchant for violence: his fomenting conflict at rallies, his support for white supremacists and haters, and most significantly his egging on armed insurrectionists to attack the capitol, even failing to protect his vice-president when threatened with murder.

Had Madeleine Albright survived a few months longer to have witnessed the select committee's hearing on the January 6th insurrection, she might have tightened her critique of Trump, the man and his madness. I read Fascism: A Warning, wanting to avail myself of the insights of a learned insider whose career has been devoted to formulating and executing policy at the highest levels. Yet being an insider may not be the most advantageous perspective to hold, as war may be too important to be left to the generals.

See Joe Chuman's Substack blog here.

The Shadowed Sun by N.K. Jemisin

This is a very good two-book series. I read The Killing Moon and reviewed it last issue , this sequel has the exiled young king (whose father was prominent in The Killing Moon) returning. He wants his throne back after spending ten years with a "barbarian" warrior society where men wear veils and women pick their lovers and hold all the wealth, including children. I love Jemisin's explorations of cultural possibilities.

The plot here is pretty direct at first glance: how, when, and will he get his throne back?

The fantasy aspect continues to be the power of dreaming that Jemisin set up in the first book. The other main character is the first woman every taken into the "Hetawa" of priest dreamers. Her speciality is healing--the most powerful priests are the "gatherers" who collect dreams from people who offer them and also gather the dreams and souls of those who are ready to pass on. They also rather often do the office of assassins, The young healer is from a class of farmers. When her family was struggling, she offered herself to be sold to help her family. She's shy and stutters and of course becomes increasingly powerful as the book goes on.

The horror this time is not a twisted monster as in the first book, but a "wild dreamer," a tortured child whose dreams fatally infect whoever is nearby.

When Jemisin is really on, as she is in these two novels, the inventive details, the controlled magic, the very human dilemmas of those with talent and power, the mix of magic with politics--can't be beat.

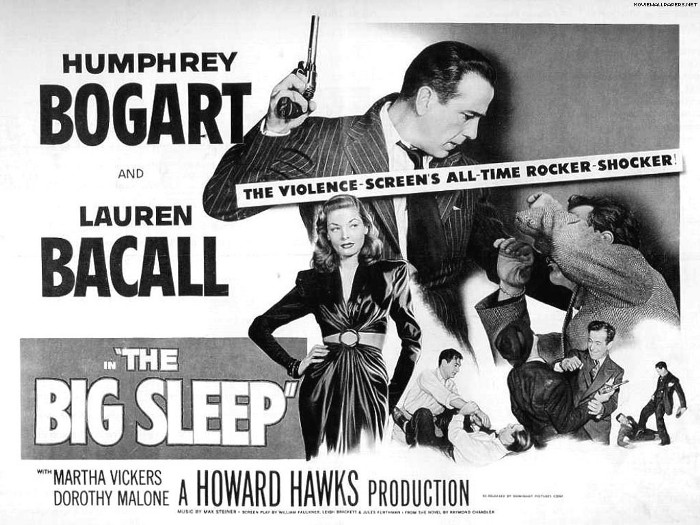

The Long Good Bye and The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

I decided to try the Progenitor instead of rereading a Michael Connelly Bosch novel. I read Chandler's last book first, and I adored the first forty pages--such fun, the familiar trope of the hard boiled PI stating his habits, getting his case. About about five eighths of the book was pretty darn fun--but it was a long book, and some of it was somewhere between a hoot and appalling. There was one scene of seduction and then the aftermath of the sex that was just ridiculous. The woman doesn't want to be an alleged nymphomaniac like her sister (who is a rich girl whose hobby is taking lovers). Every time a woman shows up in the book, actually, it's hard to take. I certainly stayed with it, and enjoyed a lot of it, but you get nauseated by the silly women not to mention the racism ("That was white of you....." is the least of it.)

I was eventually so annoyed with the book that I came up with a bit of snark that I'm quite sure someone else must have thought of first: "Raymond Chandler is the master of Raymond Chandler parody."

Then, just to be fair, I read his first novel, The Big Sleep, which has more conviction about what he was doing. The Big Sleep has all the usual--rich people to hire Marlowe and let him observe their lifestyles. Absolutely awful women. I mean the embodiments of the nasty names: bimbos and bitches and dumb blondes.

As far as I can tell there are three people Chandler actually likes in this novel (leaving aside whether or not he likes Marlowe). One is a very frail elderly rich man; one is an emphatically short grifter who doesn't live long, but stands up for his friend. The third one is a recurring cop/DA's investigator character who is old school law enforcement and pretty honest.

All the driving around vintage LA and environs is fun, as id guessing what race, ethnic group, or sexual persuasion he's going to dump on next. The Big Sleep never bored me, but I just can't take this stuff seriously.

Did Chandler or did he not know what a jerk Phillip Marlowe was?

Here are a few perhaps more balanced reviews of Chandler's work: something from Ploughshares; another from Kirkus Reviews ; and The New York Times from 1997.

NOTES ON HOW WE READ AND MORE

George Lies writes, "I've been reading more, a variety. Hummingbird by Patricia Henley, who's coming... for West Virginia University WV workshops, July 21-24 hosted by Mark Brazaitis. [Also] detective genre like old Robert Parker (Spenser series), and scanning Mary Karr's Art of Memoir. Aim to get Val Nieman novel (In the Lonely Backwater) too."

Donna Meredith on her approach to choosing and reading books, plus thoughts on books reviewed in Issue 222 : " I enjoyed [Issue # 222] of your newsletter. I like the variety of books you include. I used to teach The Member of the Wedding to high school sophomores and loved it for all the reasons you mentioned in your review. What a great job McCullers does in capturing the hot sticky summers of the South and the angst of growing up! How sweetly innocent Frankie is!

" Like you, I am a fan of Alice Munro's short stories. A favorite one that I taught was 'Boys and Girls.' Munro nails the way sex stereotypes are pushed onto children, how girls are told they must sit and behave in certain ways—and so are boys. It broke my heart at the end when the competent narrator accepts that her family's view that she is 'just a girl.' I think my students enjoyed discussing how much of our sexual identity is nurture and how much is nature.

"Your sci-fi choices are also ones I admire. Octavia Butler and N. K. Jemisin are outstanding writers, and it is probably unfair to attach a genre label to them as though that makes them inferior—or to your own novels, which have no 'fatal flaws,' quoting you in the newsletter. Modern literature wouldn't be the same without Aldous Huxley, Robert A. Heinlein, Ursula Le Guin, Arthur Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Frank Herbert, Anne McCaffery, and Isaac Asimov—and I could go on. These writers open our minds to new possibilities and help us accept the inevitable changes that will shape our future world. It doesn't matter if the writer nails exactly what will happen. What's important is that their vision awakens our own imagination. Your sci-fi novels succeed in doing this, so keep on writing them.

"My reading style is usually to tackle one book with literary value to review for Southern Literary Review, followed by a mystery or any book that qualifies as pure escapism. For example, I just read A Literary Life of Sutton E. Griggs by John Cullen Gruesser for SLR. I had to do a lot of thinking and highlighting of important material for a review of this biography of an important Black writer in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Then, needing something lighter, I plowed through the pages of Michael Robotham and Edna Buchannan mysteries that I'd seen recommended in newspapers. Next, I reread a book chosen by my book club for July, The Committee, by Sterling Watson. This novel is based on the historical actions of the Johns Committee at the University of Florida. The committee was similar to the McCarthy hearings in the 1950s, with government attacking those suspected of being homosexuals or Communists. Watson's book is so relevant today as some conservative legislators are once again trying to dictate what sorts of things can be taught in school here in Florida. Basically, I alternate serious reading with something lighter."

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Our occasional reviewer, Joe Chuman writes: "Since I retired as the professional leader of the Ethical Culture Society of Bergen Country New Jersey in January 2021, I have been fulfilling my aspiration to write more extensively. My primary outlet has been the Substack platform. My objective has been to share my views on contemporary issues and enter into conversation with others who hold common interests. Since last October, I have produced more than 40 essays of considerable length, amounting to approximately an essay each week. Happily, my circle of "followers" continues to expand. Just this week my essays caught the eye of an editor of LOGOS, a quarterly, progressive, online journal on society, culture, and politics. Founded in 2002, LOGOS claimed more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide at its high water mark. LOGOS is planning to embellish its format. In addition to its quarterly magazine, it is planning to publish a weekly edition of briefer pieces, written by a select group of opinion writers. I was invited to be one of those writers. Contributors to LOGOS have included Francis Fox Piven, Daniel Ellsberg, Jurgen Habermas, Cornel West, and other notables. I am honored to be asked to join them. The rollout of the new format should appear by the end of this year. It will extend my thought to tens of thousands of readers across the globe. It is a wonderful opportunity!"

Also, Joe Chuman's Substack blog is solid, important reading-- consider subscribing to it.

Coming in November 2022 from WVU Press: Rachel King's "Bratwurst Heaven!" Rachel King's new linked short story collection Bratwurst Haven is available for order from: Annie Bloom's Books, Bookshop ,Amazon -- and wherever else you buy your books! Rajia Hassib calls the collection "an intriguing and tenderly rendered study of this flawed world we call home." There is a virtual launch through Annie Bloom's on November 1, 2022, and then in-person readings in Baltimore, Washington, DC, and more.

Nikolas Kosoff's story about a boy with a unique world view is available online at "Evolution." The boy's world view--and his world-- are very interesting. It's a gripping story of school life, New York City, making friends--and seeing, if not solving, a mystery.

Check out Harvey Robins on how New York City could return to putting the needs of the public over the needs of corporations (for-profit and non-profit both ) in public spending.

Kelly Watt has a flash fiction online at Microlit Almanac. Also take a look a her book blog.

THINGS TO READ ONLINE

Terrific flash fiction by Shelley Ettinger: "Banana Chair Season!"