Summer Starter 2015

Session I6-8-15

MSW Home

Sessions: One, Two, Three, Four

Getting Started with the Summer Starter:

How This Class Works

Welcome to the Summer Starter 2015 with Meredith Sue Willis. This class will focus on topics I choose, ideas I get from the writing you turn in to me, and topics you want to discuss. Please feel free at any time to send questions or comments or suggestions that can be shared with the group. Unless you specifically tell me otherwise, I will consider using samples of your writing in upcoming posted lessons for the class.

Here are some things to keep in mind.

Some writing exercises are for your use only, and some assignments (usually the MAIN ASSIGNMENT) you send to me. You may substitute, but everything you send counts toward the total of 7,000 words for the whole class.

Sessions go online on Mondays, with an e-mailed note that it is up and available.

Send your homework to me at MeredithSueWillis@gmail.com by midnight of the due date— Session One homework, for example, is due Sunday night, June 14, 2014. I'd prefer the homework BOTH in the body of the e-mail AND attached as a Word, WordPerfect, or Rich Text file. If you send the homework sooner, I'll try to turn it around in time for the next session, but the responses to your work will most likely not be coordinated with the lessons very directly. Therefore, don't wait, but go ahead to the next session.

You may send up to 1750 words a week (more if you want, but subtract the amount from the total). Less is fine too. 1750 words is roughly comparable to 5 double-spaced single-sided typed sheets in a font no smaller than Times New Roman 12 point.

There is always a MAIN ASSIGNMENT, but remember you are welcome to substitute. You do not have to do the exercises, but I recommend that you at least try some as warm-ups and for the possible generation of new ideas. Only submit whatever you want feedback on. Here are a couple of hints about how to use the sessions:

One way to use the exercises is to try several. Do them rapidly, as a way of getting ideas for yourself.

Try doing them with a kitchen timer set for ten minutes. This will force you to go for content rather than beautiful sentences. Again, these exercises are about getting ideas, exploring, and experimenting.

When possible, do the exercises as a part of your project.

Enough rules and regulations! Let's write something!

Exercise One: You've already sent me a note about what you'll be working on this month. Now

write a short note to yourself saying (a) what you hope to accomplish during the month and (b) when you will be working on your project: On Monday evenings after the new session goes up? Every week-day morning? Sunday mornings only? Try to be realistic, and check back later as to whether you are doing what you thought you would.

Exercise Two: Set up a paper or digital log for your work this month. Simply note down when you worked (maybe where, if you carry your computer around with you) and some indication of what you accomplished. This could be numbers of pages or a word count, or simply "I drafted the first half of the scene where they meet for the first time." At the end of a writing session, I often note the present page count and the word count with the date. When I get to revising, my objective changes to making all the numbers (except the date) go down!

If you are already logging your work, let me know how you do it so I can share the ideas with the class.

Getting Started with Structure

The last time I taught one of these four week online courses, I focused on imagination in prose narrative. This time, I intend to focus on structure (both macro, the shape of your book or novella or story) and medium-size (scenes). We'll spend some time on revising as you go. I hope to sharpen the focus of the class once I begin to see your work.

With a couple of exceptions, the people taking this class are engaged in longer works-in-process. There is one projected short nonfiction piece and one short children's novel. Even short pieces, though, need strong structure, although sometimes a short story's entire shape comes to the writer at the very beginning.

For longer works, though, thinking from the beginning—but with a willingness to change directions at any time—about how to organize and structure the work is, in my opinion, part of the process.

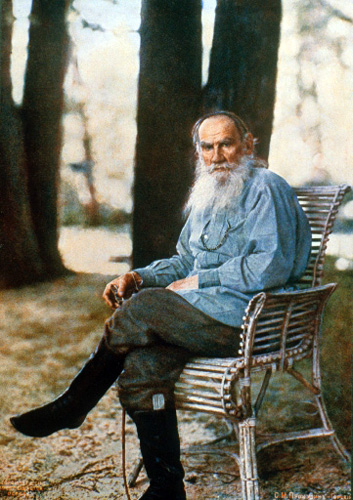

To use a big famous example, I always imagine that early on, as Tolstoy (right) started writing Anna Karenina—maybe soon after reading the newspaper clipping that he claimed was where he got his idea—that he began to realize his story was not just about the suicide of a beautiful society lady, but also about marriage, or rather, marriages. I imagine that early on he came up with the idea of using three contrasting marriages: there is Anna's marriage in which the woman strays; there is Anna's brother's marriage in which the man strays; and there is a third marriage (Anna's brother's wife's sister's marriage) in which both partners strive to be faithful.

This is not, of course, the plot of the book. This is the larger structure to which the plot gives cohesion and momentum. Tolstoy was always looking for something larger than the story of an

unhappy society woman who commits adultery and then can't stand the social ostracizing she receives. Tolstoy would be writing about marriage and its stresses, and about family structure. He needed—and I would maintain prose narrative writers all need—big containers to hold the various ideas he came up with and, especially, the scenes he wrote. I call these "big bins" that organize our thinking and are essential to containing a novel.

Exercise Three: What are the three biggest conflicts in your project? What are three themes that interest you as you write? (Three is, of course, arbitrary, but these are exercises.)

Exercise Four: List the the three main places where things in your book happen.

Exercise Five: Name the three main people in your project.

I have a number of times organized a novel by chapters that follow each of several point-of-view characters. I don't always put their chapters or sections in the same order, but I usually finish all the people before repeating one.

Once I have a good draft, I often break my own little rule, but I noticed recently in doing one final go-through of a novel before submitting it to an editor, that two of the six point-of-view characters didn't show up until nearly halfway through the book. There is nothing forbidden about this, but I wanted a reader to be aware of how many people were going to be highlighted, so I shuffled the chapters around until each character had had one chapter—had been introduced— before I started over again. I wanted the reader knew what to expect—that there would be several points of view. That was, of course, during revision. In drafting, I thought a lot about which people I wanted to use for points-of-view, but not much about reader expectations. That's a final stage consideration, in my opinion.

Do I have to keep saying "in my opinion?" It's all my opinion. Writing fiction and memoir is not a precise science.

Exercise Six: Take the the list of people or places or conflicts or even themes (what I'm calling the "bins"), and make a list of five scenes under each that you have been planning to write or have at least vaguely imagined you might put into the book. If you don't have five in mind yet, make up a couple.

Exercise Seven: Here is a more directed exercise. Imagine or remember a face. This might be someone you've actually met—from childhood, or a face you saw on the train last week. You may also, if you are working on an ongoing project, choose a character you've already begun work on or plan to use.

For this exercise, re-describe the face only in more detail than you usually do.

Next write some back story for this person.

Who are the two most important people in this one's life? Briefly sketch a sentence about her or his relationship with each of them.

What is the conflict?

Where might this lead you in a story?

Do you have a way to include this in what you are writing? In dialogue, perhaps?

Exercise Eight: Set the kitchen timer for three minutes and sketch out a bare bones outline of the main events in your book or story. The exercise here is to do it very rapidly, whether you have done it already or not. Try to write without adjectives or adverbs.If you are well engaged in your project, compare this brief exercise to whatever summary or notes or outline you've already written.

Does the quick sketch put the emphasis somewhere different? Does it suggest a different order or climax?

Starting & Structuring Scenes with the Senses

Of all the art forms, the written word depends most on the imagination of the person receiving the work. I would submit that the other arts offer far more sensual input: the haunting sound of violins, the

sudden jump in a movie that makes the viewer gasp, the thick, rich texture of an Impressionist painting seen up close.

The written word, however, is a step removed from the senses: the reader must create the imagery for herself or himself. The demand for imaginative participation is at once the strength and bane of written literature. The reader is not merely a consumer, but a co-creator. In the movies, as in the scene at left from the first Godfather movie, much, much more is given to us. (Michael Corleone is about to wreak vengeance on his father's enemies). Before trying to enthrall a reader, we have to enthrall ourselves with emotional content and with the imagined sensory input. This necessity, however, is also a great tool for drafting and imagining our scenes. You can see my definition and discussion of scene here.

Psychologically, we enter a "scene" in real life—the room where the party is going on, the office of the boss who will interview us, the street where the demonstration is underway—from our groundedness in our bodies. Scenes are in real life, and often in prose narrative, organized by what we apprehend through our senses. Usually, but not always I have the long distance of vision first (but I may hear the murmur of the crowd before I see it). I come closer and begin to hear details, perhaps to feel the warmth or the cool breeze or feel the thud of the bass speakers. I smell ocean or garlic in oil.

This natural entry into a scene is one of the reasons writing in the first person is often easier than writing in the omniscient. Which details to choose seems clearer. I get into a car when my co-conspirators come to pick me up, there is my excited little shot of adrenalin (we're on our way!), I smell someone's cigarette breath, I feel my partner's thigh pressed against mine in the crowded back seat—and we're already well into the scene. Close third person works much the same way, and omniscient can too. The senses, then, are a great way both to write the beginning of a scene and more importantly to write a scene with a natural structure and organization.

Try the exercises below with a scene you are having trouble with a scene or looking for a new one.

Exercise Nine: Take a scene you haven't written yet, or are having trouble with, and write or rewrite it following a logical structure via the senses. Start with the most physically distant sense—what the character sees—then pull in closer with sounds, then all the way close to touch and smell and even taste. People can be talking as this goes on, or, for that matter, having a knife fight, but organize your scene around getting close enough to include the intimate senses, touch and smell and even taste.

Exercise Ten: Try the opposite order: the narration (of the POV character) is deep in touch or smell, possibly even with the eyes closed. Perhaps she or he then hears sounds, or dialogue, opens the eyes and sees. This might be waking from a nap or in a hospital, or from lovemaking or simply musing about the past.

In both these exercises, try to see where you are led. The point is not a slavish ticking off of the senses, but a way of getting new ideas or organizing old ones.

Main Assignment

Write a scene in which one of your characters changes. This can be big or little, a realization or some change forced from the outside. This happens, of course, to children and elders as well as to young people and people in middle age. Consider structuring your scene with the senses, but keep in mind that the point is to get you started and restarted. Make it work for you!

Remember: substitutions are welcome. If you are moving full speed ahead on a project, don't stop! Send any passage you want feedback on.

Extra

One of the members of this class, whom I've known for a long time, asked a question about the use of the em dash—the long one. An editor she is working with, she says, is "very concerned about my use of the em dash, and we have discussed it. I was encouraged to use it so much when I read Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch. Then, tonight I was worrying about [it again] and sat down to read Jonathan Franzen's story in this week's New Yorker. Again, there were several em dashes—including the first paragraph. I find it very useful. Do you have any thoughts about it?"

I answered that I use the em dash, and I suppose my only problem is that when people overuse it (and the exclamation mark), it sounds gushy—oh my!—too many!—we have to be careful! On the whole, I'm in favor of using any tool available for expression, because we prose narrative writers have relatively few expressive symbols and signs at our disposal, and I'd hate to give up any of them.

***

Subscribe to Meredith Sue Willis's Free Newsletter

for Readers and Writers:

Images and photos found on the various pages of this web site

may be used by anyone, but please attribute

the source when it is specified.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.