A Journal of Practical Writing

Updated 2-15-25

Contents

(Unattributed Articles by Meredith Sue Willis)

February 2025 Adventures in the Written Word with Danny Williams!

Sample from an earlier Danny Williams article:

Well, I’m still into this novel writing thing. You may be sick of hearing about it, it’s been going on so long, but you didn’t pay anything to get in here, so you probably have no legal recourse. Who would have thought writing a novel would be so time-consuming? I was figuring a month, one of those 31-day months. Write 2,000 words a day for 30 days, then on the 31st clean up any typos. It’s not working out that way. But with all this time I’m putting in, I think I’m learning some things.

Learned Thing One: Get as many people as you can to read what you write, as soon as possible after you write it. I’m in this online novel writing class out of New York University (Go, Fighting Violets!), so in the past couple of days I’ve shared ten pages of my work with the other students, and some of their comments are coming in....

Read the Whole Article here....

My Historical Fiction, True Crime novel, THE KELSEY OUTRAGE, The “Crime of the Century” was published by Black Rose Writing in January, 2024.

My journey from writing to publication began in Meredith Sue Willis’s Novel class at NYU. I wasn’t sure exactly when I had taken that first class, but on picking up my copy of Meredith’s book, OUT OF THE MOUNTAINS, I read her inscription: “To Alison, with best luck on your novel! 10-24-11.”

Oh, no! I thought. Did it really take me that long? For anyone attempting to write or publish a book, fear not. It probably will not take you that long. But if it does, take comfort in one of the things I learned along the way: each book in its own time. Whole article here....

Alison Hubbard invites readers to reach out with questions or comments to alisonhubbardauthor@gmail.com. She says, "I don’t have all the answers, but am happy to help."

The Kelsey Outrage is available from the usual online suspects like Amazon as well as from Bookshop.org, the online store that shares profits with brick-and-mortar stores.

Two by Danny Williams

mechanics: replace

The “replace” function can be a powerful tool for fine-tuning a text. (In Word, it’s under “edit” on the formatting bar. There are a couple of ways I like to use it, and if I am in early enough on a manuscript and the author is open to my input, I often recommend they do it themselves. (When I am fortunate enough to have work at all (wink-wink).)

First, “replace” can identify clusters of is/are/am/been/was/were verbs, the words a more innocent age labeled as “copular verbs.”. Nothing wrong with any of these words, but probably you want to be aware if they are massing anywhere. Rewriting with a stronger verb can often improve a sentence. Plus, every passive sentence contains one of these words, and probably you don’t want to dwell too long in passive-voice land. (Yes, passive sentences are necessary. They are especially useful if you or your character want to avoid stating the sentence’s subject. Richard Nixon: “Mistakes were made.”)

So here’s how. Replace each of these words with boldface. (I like to go a chapter at a time.) Now you can spot densely-populated regions by just swimming your eyes over the pages. I wish I had thought of this 40 years ago. The first paragraph of the liner notes for that Glenville recording still haunts me.

One of my weaknesses as a writer is an occasional over-fondness for long sentences. To identify passages where I’m channeling my inner Faulkner, I replace every period with a couple of paragraph symbols. Since I’m already adding space after each paragraph, this makes every sentence clearly announce its girth. To do this in Word: From the “home” tab, go to “editing” (the little magnifying glass), open “replace,” then the “special” menu. Here are all the formatting commands. Just put a period in the “find what” field and a couple of “paragraph marks” in the “replace with” field. All your sentences are now isolated, and you can readily see any clusters of three- or four-line—or longer ones. Even though I feel like every one of my tumescent constructions is a thing of beauty, I shed not a tear as I bust up gangs of them.

I also like to temporarily embolden “very,” and any other throw-away words I suspect may be lurking. of, that, really

Email me (editorwv@hotmail.com) if you have any comments on this or anything else. I have an opinion on nearly every topic. And tell me what you’re working on. Don’t send a sample, just a few words about your baby. I’ll reply with an encouraging sentiment or two.

Last book that kept me up literally all night: The Red Tent, by Anita Diamant. ISBN 13: 9780312195519

March 2024 Adventures in Editing with Danny Williams

In some police departments, trainees are required to zap themselves with a Taser. The idea is that, if they are going to be carrying this thing and potentially inflicting it on people, they ought to be aware of what it feels like.

With similar reasoning, I am now writing a novel and editing it myself. It’s only fair that I experience firsthand the kind of grief I visit upon my authors. (Expect a giant plot twist in this column, nine paragraphs down.)

The story comes from a character I developed for an author about 10 years ago. One of his people needed a lot more substance, so I gave the writer an example of a detailed backstory and personality. He didn’t like my idea at all, and he wrote his own. That’s a fine example of me succeeding at my job. I don’t know if he appreciates how my failure at improving his work led to improvement in his work. I kind of hope not. It’s fun to feel sneaky.

That left me with an unbooked character, somewhat fleshed out and ready to go. He’s an engineer in his early 60s. A car accident a few years back killed his wife and severely bunged up his left leg. Now he’s cynical and withdrawn. The “action” will be him making a few modest steps toward re-engaging with life.

Danny Williams, editorwv@hotmail.com

A Challenge: Revising 3rd Person to 1st Person POV by George Lies

Switching POV from 3rd Person to 1st Person is a revision challenge. The primary focus of a writer must be to act like the character. This approach has been found in many writing books for almost every POV. In changing POV from 3rd to 1st Person, however, the syntax and context need to be rethought and revised in the narrative, to make the text readable. The text simply will not read clearly by only replacing he/she/they with the 'I' of 1st Person.

This brief article applies to fictional characters, since many writers use the 1st Person 'I' to draw on their own stories and experiences. One benefit of revision is gaining a strong grasp of a scene as well as the larger plot or character arc. A 1st Person POV implies speculation, by the character, that is—what's on the character's mind, right now. It's in the now, no need to use italics for internal 'thoughts'. An extra: a flashback can flow easily in past tense into text. Read more...

Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once?

by Eddy PendarvisThe omniscient point of view in fiction, in which the narrator uses the third-person voice to tell the story and, being “all-knowing,” often reveals the thoughts and feelings of major characters and perhaps even of minor ones as well, is probably the most used point of view in the history of published fiction. Writers today are sometimes warned against using the omniscient narrative for that very reason—it may seem old-fashioned. They’re also advised that it may set the reader at an emotional distance from the main characters, and it can lead to “head-hopping.” In fact, irritation at the term “head-hopping” is one reason I’m writing about omniscient narrative. The term bothers me because it implies that moving from the thoughts of one character to another in fiction is poor writing. Even though I understand that “head-hopping” is probably meant to refer to confusion readers may feel if the narrative movement from one character’s thoughts to another character’s thought is clumsy, the derogatory term strikes me as a form of “poisoning the well,” a rhetorical ploy to turn listeners or readers against an idea or a person’s ideas before offering an argument against that idea or person’s ideas. Read More....

One Story, Forty Submissions, Ten Years by Ed Davis

Every now and then something happens in my writing life that so stuns or satisfies me that I need to share the wonder of it. Such a thing happened recently when I had a story published the same day it was accepted. That's remarkable but not nearly as important to me as the fact that it was accepted after 39 submissions over ten years! Read more....

Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing: Considerations and Practical Approaches

I have been thinking the past year a lot about the need for many voices to be heard in the quest for justice, and about the issue of who should write those voices. This essay is about some of those issues, along with offering a few practical approaches to writing about people unlike ourselves.

Many years ago, in the first writing seminar I took in college, there was a young woman I'll call Amy who wrote a story about lynching. Amy was a young white woman from the American South. I'm white too, and so was the professor, and, I believe, so was everyone else in the seminar. This was in the mid nineteen sixties, and I remember feeling there was something wrong with her story. It felt thin, like an inexpert line drawing. We were all very silent when she finished reading, and the professor was gentle, but his advice was that she should probably write about something she knew.

I still wonder why she wrote that particular story, which was most emphatically not based on her own experience. Read more....

A Response from Kate Gardner

My thoughts as a White woman and writer on your essay on cultural appropriation: I think it is important for white-skinned people –who seem to be the primary audience for your essay –to understand and accept two things about themselves.

First, White people are racist -- which is different than being a racist). We can’t help it. We’re born into the fable of Whiteness, which is central to our country’s economic, social and cultural history and mythology. The sins of genocide and enslavement committed by our European ancestors and then justified through an invented White superiority and dehumanization of people of color have not yet been reckoned with. America has yet to take on the kind of Truth and Reconciliation Commission that played an important role in healing the psychic and relational wounds of Black and White South Africans. Read more....

Pieces from an Editor's perspective by Danny Williams

Book Reviews for Writers: Danny Williams on Meredith Sue Willis's Love Palace

Real Life Adventures in Editing by Danny Williams

Names in Fiction by Danny Williams

Should Your Book Have a Price on the Cover? by Danny Williams

More Hints from a Professional Editor by Danny Williams

Also, check out this Danny Williams extra on publishing with university presses.

More

- The Ninety-Nine Day Novel Course by Alison Hubbard

- Best Writing Advice I Ever Heard/Best Novels for Learning to Write a Novel

- The "Stakes" Method of Outlining by Suzan Colón

- MSW on Character Development Through Changing Names

- Thoughts and Exercises for Writing Physical Action

Literary Recycling by Ed Davis

Five Lessons from George Eliot

Structuring with the Raised Relief Map Technique

Rolling Revision: The Interplay of Big Picture and Close-Up

Some Thoughts on Self-Publishing by Allen Cobb

(See Allen Cobb's website here)Making Your Own Deadlines by Anna Egan Smucker

A Revision Technique for Novels

Literature, Genre, and Me

A short inspirational passage about the meaning of art.

On Using the Omniscient Point of View Successfully

Anthony Trollope's Discipline

A Conversation About Keeping Drafts with Suzanne McConnell, NancyKay Shapiro, Diane Simmons, and Meredith Sue Willis

Those Handy Little Binoculars by Sarah B. Robinson

On Writers Groups by Troy E. Hill

Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction

For links to a list of various articles on the web of special interest to writers, click here.

A Challenge: Revising 3rd Person to 1st Person POV

by George Lies

Switching POV from 3rd Person to 1st Person is a revision challenge. The primary focus of a writer must be to act like the character. This approach has been found in many writing books for almost every POV. In changing POV from 3rd to 1st Person, however, the syntax and context need to be rethought and revised in the narrative, to make the text readable. The text simply will not read clearly by only replacing he/she/they with the 'I' of 1st Person.

This brief article applies to fictional characters, since many writers use the 1st Person 'I' to draw on their own stories and experiences. One benefit of revision is gaining a strong grasp of a scene as well as the larger plot or character arc. A 1st Person POV implies speculation, by the character, that is—what's on the character's mind, right now. It's in the now, no need to use italics for internal 'thoughts'. An extra: a flashback can flow easily in past tense into text.

A few revision pointers:

Foremost, I've found that you the writer must internalize a character, the traits or habits, and respond with short comments, one word on occasion (see example one below). This is a huge benefit in getting to know a character and leads to tighter text, too. A second benefit is the use of more 'active' verbs instead of passive or past-tense verbs (see example two below). This may address feelings and emotions, if the revision better describes chill in the air, odor of garbage, or sipping of tequila. See one example below

One has to not overuse 'I' so as not to bore the reader. Avoid if possible, 'I go to the room" or 'I'll think about it' or "I fix my breakfast". Go to the action or setting directly. One has to rethink the text, so it captures the POV of a character (not the author-narrator) and in the setting or action. You may need to drop details or delete exposition text, going from 3rd to 1st Person. The benefit is a character who uses short internal comments, a thought, or a reaction in a scene.

You'll find dialogue needs to be more direct, including 'tags,' such "I say" and not necessarily "I said" in a setting that is in the now, the present—one person to another character. In 1st Person, a character can often refer to pending items or add subtext of a thought regarding the current one-to-one conversation. Use of 1st Person POV can also show a change in direction, or reference to a 'recalled' incident or a 'have-to-do task'.

Finally, stay away from info-dumping, the drop-in background of a character found in the exposition—that is, who is this person? Think how to describe physical details (there's always looking at old photo or a reflection in mirror options). So, a writer needs to be creative, find other ways to show the character's position, rank, education, lifestyle. The benefit is use of 1st Person 'I' avoids boring 'info dumping.' The 'telling' of background is not 'showing' and no one in 1st Person will 'tell' a reader their resume.

Example #1: Internalize 1st Person POV As Character—

Original 3rd Person POV Text: "On a Tuesday afternoon in early Fall marked by grayness beyond the window of Woodburn Hall, professor Charles Delacroix did not plantodig into the past in resolving his pain. He contained the anguish over his sister's death and often paused in mid-sentence during a lecture on the Roots of Mexico's Independence. He struggled for resolution and thought only of getting away from the campus crowd."

Revised 1st Person POV Text: "A grayness fills my heart like the morning mist beyond the window of Woodburn Hall. Not into teaching university students, still resolving my anguish over my sister Michelle's death and, as students notice, I often couldn't finish a sentence, let alone an hour lecture on the Roots of Mexico's Independence."

Example #2: Active vs. Passive/Past Tense Verbs in 1st Person—

Original 3rd Person POV Text: "A group of four students approached him. Two young women from West Virginia, a guy from Pittsburgh, and an international exchange student from Mexico, from the town of Guanajuato. He figured on quickly responding to their questions.

Revised 1st Person POV Text: "A girl from Charleston, our state capital, asks, "What's the best way to do our project on Mexico history? Four students stand near the lectern, two from West Virginia, one from Pittsburgh, and a Mexican exchange student." - "Work as a team," I say. "Discuss the topic and develop a project."

Free Indirect Discourse: Two (or Three) Points of View at Once?

Eddy Pendarvis

The omniscient point of view in fiction, in which the narrator uses the third-person voice to tell the story and, being “all-knowing,” often reveals the thoughts and feelings of major characters and perhaps even of minor ones as well, is probably the most used point of view in the history of published fiction. Writers today are sometimes warned against using the omniscient narrative for that very reason—it may seem old-fashioned. They’re also advised that it may set the reader at an emotional distance from the main characters, and it can lead to “head-hopping.” In fact, irritation at the term “head-hopping” is one reason I’m writing about omniscient narrative. The term bothers me because it implies that moving from the thoughts of one character to another in fiction is poor writing. Even though I understand that “head-hopping” is probably meant to refer to confusion readers may feel if the narrative movement from one character’s thoughts to another character’s thought is clumsy, the derogatory term strikes me as a form of “poisoning the well,” a rhetorical ploy to turn listeners or readers against an idea or a person’s ideas before offering an argument against that idea or person’s ideas.

A better reason for my interest in omniscient narrative cropped up when I was reading a 2021 republication of How to Read a Novel, by Caroline Gordon, whose work I’d never read, but whose reputation as a novelist was somewhat familiar to me. In How to Read a Novel, first published in 1953, Gordon offers several views on how readers should approach novels; but of special interest to me was her use, in Chapter Six, of the concept of the “effaced narrator.” She offered examples of this form of third-person narration by quoting from Gustav Flaubert’s Madame Bovary; but even after reading her examples I wasn’t sure I understood what she meant by “effaced narrator.” Here’s one example she quoted from a passage in which Emma Bovary has received a letter from her lover ending their illicit affair. She was interrupted in her reading of the letter by the presence of her husband and had to put the letter away:

Then she tried to calm herself; she recalled the letter; she must finish it; she did not dare to. And where? How? She would be seen! “Ah, no! Here,” she thought, “I shall be all right.”

Gordon describes this excerpt as presenting Emma from two viewpoints: that of the narrator and that of Emma herself. As I see it, most of the quotation is typical of the conventional omniscient view and is clearly the narrator telling us about Emma’s thoughts and feelings: “Then she tried to calm herself: she recalled the letter,” is typical omniscient narration; but the next portion—“she must finish it’ she did not dare to. And where? How? She would be seen!”—is ambiguous. It includes the third-person pronoun “she,” but it describes Emma’s thoughts and feelings without explicitly attributing them to her. In the next sentence, the narrator returns to conventional omniscient narrative and attributes the ideas and feelings to Emma herself: “Ah, no! Here,” she thought, “I shall be all right.”

What Flaubert achieved with the “effaced narrator” technique, in which he describes character’s perspectives, Emma’s in particular, in this way, writes Gordon, is “the vividness he would have achieved by having Emma tell her own story” through a first-person narrative, and, “at the same time” presents Emma’s upset from a somewhat objective point of view.

This “double vision” idea intrigued me, but I might not have followed up on it if I hadn’t come across on-line discussions and essays on “free indirect discourse,” sometimes called “free indirect style.” Both of these terms seemed to refer to the kind of narration described by Gordon in explaining her “effaced narrator” point of view. Various essays and blogs cited examples of free indirect discourse in 19th century novels by Jane Austen (Sense and Sensibility and Emma) as well as in 20th century novels by Virginia Woolf (Mrs. Dalloway) and in short stories by James Joyce (“The Dead”) and Flannery O’Conner (“A Good Man is Hard to Find”). What the many quotes exemplifying the device have in common is the lack of attribution of a thought or feeling to the character being represented in an omniscient, third-person point of view.

There appears to be a whole industry of critical delving into the use and nature of free indirect discourse. Timothy Bewes, in the first chapter of Free Indirect: The Novel in a Postfictional Age (published in 2021) reviews some of this work. Among the literary critics and theorists’ ideas he refers to is literary critic. D. A. Miller’s description of free indirect discourse as a device that “simultaneously subverts the character's authority” and also signals “deep or unfathomable emotion” that the character might not be able to articulate at the time.

The “free indirect discourse” in omniscient narrative is in stark contrast to the use of a narrative technique common to many 19th century novels, in which the omniscient narrator often assumes a more obviously detached view of a character’s feelings, thoughts, or actions—a view that is sometimes avuncular and sympathetic, and sometimes rather harshly judgmental. This kind of narrative was so common that the lack of a judgmental narrator, rather than—as Gordon calls it—an effaced narrator, landed Flaubert, along with his publisher and printer, in court. In The Trial of Madame Bovary, author Chris Robert contends that free indirect discourse used by Flaubert offended the French authorities for “inhabiting Emma so fully” that no overt criticism of her adulterous behavior is offered in the narrative.

One of my favorite authors, Thomas Hardy, didn’t get into trouble with the law, but was heavily criticized for his sympathetic observations on his heroine, Tess, whose actions lead to her arrest on the charge of murder, in Tess of the D’Urbervilles. His empathy with his major character in that novel and others, however, was conventional in its literary expression; the narrator’s observations are clearly the narrator’s own. Here’s a quote from the end of Chapter 35 in which the narrator judges the husband’s rationale for rejecting Tess as his true love after she confides to him that she was raped prior to their marriage:

He [Tess’s husband] argued erroneously when he said to himself that her heart was not indexed in the honest freshness of her face; but Tess had no advocate to set him right.

Here’s an example of a conventional narrator’s direct discourse from another of Hardy’s novels, The Woodlanders:

A perplexing and ticklish possession is a daughter, according to the Greek poet, and to nobody more so than to Melbury [father of Grace Melbury, about whose future he is concerned].

Hardy’s narrator feels free to refer to authorities such as Greek poetry (Menander in this case) and the Bible and other sources to amplify his judgments of characters and situations. This type of narrative move was common in his century and less common in the next.

A recent issue of the New York Times Review of Books includes an article entitled “Very Free, Indirect” about Katherine Mansfield, whose fiction was published only about a decade after Hardy’s last novel was published. Her short story, “How Pearl Button was Kidnapped,” published in 1912, makes highly creative use of free indirect discourse. In it, a little girl is invited, by two women who happen past her yard, to go with them. In conventional omniscient narrative, Mansfield describes the two women: “One was dressed in red and the other was dressed in yellow and green . . . . They had pink handkerchiefs over their heads, and both of them carried a big flax basket of ferns.” Pearl leaves with the women, who walked “slowly, because they were so fat, and talking to each other and always smiling.” The suspenseful tension between Pearl’s apparent interest in the strangers and the possible threat to Pearl is unrelieved until the last sentence of the story. Meantime, the narrator concentrates on Pearl’s impressions. (I’ve put the free indirect discourse in bold font):

They walked a long way. “You tired?” asked one of the women, bending down to Pearl. Pearl shook her head. They walked much further. “You not tired?” asked the other woman. And Pearl shook her head again, but tears shook from her eyes at the same time and her lips trembled. One of the women . . . caught Pearl Button up in her arms. . . . She [the woman] was softer than a bed and she had a nice smell that made you bury your head and breathe and breathe it.

Mansfield offers the only example of free indirect discourse incorporating the second person “you” that I came across. With this pronoun, she not only brings Pearl’s feelings to the fore, she implies that those feelings are familiar not just to the narrator but to others, including readers of the narrative. A first-person point of view (without using the first-person voice), second-person voice, and third-person POV are all present in this sentence in the intriguing story with its not altogether happy ending.

Free indirect discourse has been used in fiction for a long time, maybe even since medieval times according to some theorists; however, it seems to have been referred to as a special technique, beginning with European literary theorists in the mid-twentieth century. As I live in West Virginia, I was interested to see that West Virginia native, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., was credited by some as having coined the term “free indirect discourse” in The Signifying Monkey, published in 1988. I’m not sure that’s accurate, but he apparently did use the term in describing Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Interest in free indirect discourse persists, its use described as unique to prose fiction and its significance intimately linked to a modern world view. Timothy Bewes notes in Free Indirect: The Novel in a Postfictional Age that this kind of narrative is considered to be a central feature of the modern novel often seen as simultaneously presenting and subverting a character’s thought and elevating the narrator as seeing beyond it in language that, according to some theorists, reflects the ideology of the current sociopolitical order, but differs from the older judgmental narrative asides (such as those by Hardy), imbuing such discourse with mystery in withholding its source.

For my purposes as a writer and reader, the main value of understanding free indirect discourse as a narrative technique goes back to Caroline Gordon’s point about the intense vividness and flexibility offered by the effaced narrator. Free indirect discourse offers the immediacy of the first-person point of view, the depth and freedom of the omniscient point of view, and a kind of poetic mystery in seeming to be uttered by a voice that is somehow also beyond either the character or the narrator.

Cultural Appropriation in Creative Writing:

Practical Ideas for Alternatives

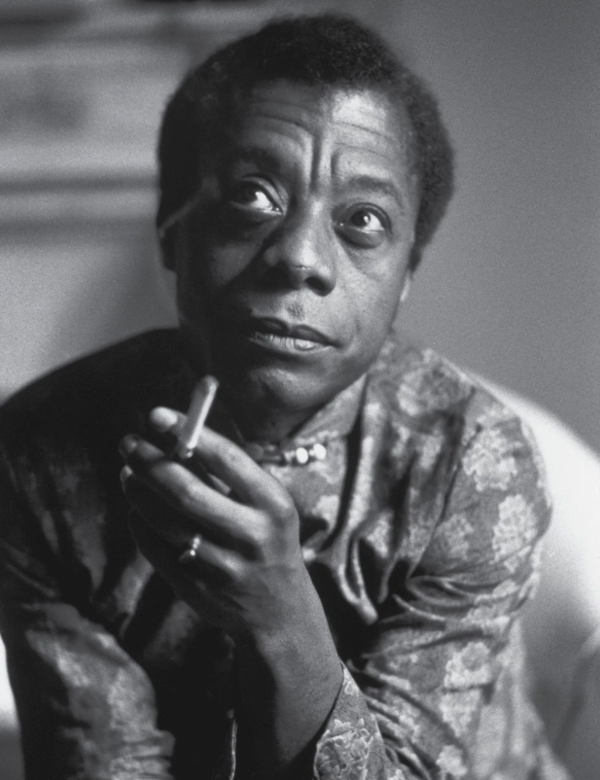

Lillian Smith James Baldwin

I have been thinking the past year a lot about the need for many voices to be heard in the quest for justice, and about the issue of who should write those voices. This essay is about some of those issues, along with offering a few practical approaches to writing about people unlike ourselves.

Many years ago, in the first writing seminar I took in college, there was a young woman I'll call Amy who wrote a story about lynching. Amy was a young white woman from the American South. I'm white too, and so was the professor, and, I believe, so was everyone else in the seminar. This was in the mid nineteen sixties, and I remember feeling there was something wrong with her story. It felt thin, like an inexpert line drawing. We were all very silent when she finished reading, and the professor was gentle, but his advice was that she should probably write about something she knew.

I still wonder why she wrote that particular story, which was most emphatically not based on her own experience. I'm fairly sure she was responding to the Civil Rights movement and current events. I imagine she might also have had a horrified and shocking realization of the evil in her own culture, perhaps even in her own family. But why did she insist on writing this from the point of view of a Black person?

Today, I teach fiction writing myself, and I would never discourage any writer from writing anything at all in their first draft. This essay is not about freedom of self-expression. There is nothing so important and powerful to a writer as that first out-pouring of inspiration, anger, images–whatever! Try out the voice of someone of a different gender, gender identity, or sexual preference if that feels important. Try out someone of a different race, different culture, different time in history.

But the powerful first spewing is only the beginning. Little children think the first thing they write is chiseled into the record permanently, but adult writers ideally understand they can make changes in the second and third looks. Once they have a draft, they can think about the form they are using, about audience. They have their whole lives and all their personal and observed experience to put into their writing. I'm in favor of everyone borrowing, stealing, plagiarizing--appropriating anything--in a first draft. You can always change it later, and very often you should. The real question for a writer isn't about offending someone or political correctness, but about whether you are writing what you really want to write, and whether what you are writing works.

James Baldwin's second novel Giovanni's Room (after a highly successful first novel, Go Tell It On The Mountain set in Harlem) was rejected by Knopf because they said he really shouldn't be writing a novel where everyone was white. They wanted more about life in Harlem. They told him he was a "Negro writer," and a book about white people (in fact, largely about homosexual white people) was going to ruin his career. Ultimately, another publisher took the book, and Baldwin, of course, went on to be one of the greatest stylists and voices of the twentieth century. I only read Giovanni's Room recently. It is a fascinating story of a troubled young man full of mid twentieth century self-loathing, and also of a certain milieu in Paris. There is plenty to say about the book (see an excellent New Yorker article by Colm Tóibín).

But here I want to focus on Baldwin's use of a narrator from a different racial background than his own. Mostly, I think the voice works very well. It is not a novel about whiteness, and it uses settings and, presumably, characters that Baldwin knew first hand. The fault I find is that the narrator, David, comes from a kind of generic American white culture that seems not only bloodless but imprecise and far too generalized. This is, in the end, a small matter, because that's how David sees his own background, and the book's focus is elsewhere. People still tend to prefer Baldwin's other work with its frequent focus on race, but Baldwin was always going to write whatever he damn well pleased to write.

This is the stance most writers and teachers of writing take on these issues of appropriation: "Don't tread on me–I am Writer, hear me Roar." It is the stance Colm Tóibín takes in the New Yorker piece mentioned above:

A male novelist can make a woman; a contemporary novelist can make a figure from the past; an Irish novelist can make a German...a straight novelist can make a homosexual; an African-American novelist can make a white American.....All novelists can slowly refashion themselves and then, as a result, characters emerge on the page and then in the reader's imagination....It is called freedom, or what James Baldwin, in another context, called ''the common history—ours.''

Thank you, James Baldwin: yes, we do have our common history, our common humanity. Of course we have the right, perhaps even the mandate to use our imagination to make leaps into people unlike us. "What if instead of who I am, I had been..." is probably the most powerful prompt in fiction.

On the other hand, what we have the right to do–what we are free to do–is not the end of the story. Just as we look for cliché and stereotype in our choice of words, so should we look for cliché and stereotype in our voice, characters,our story arc. In revising, we want to use all parts of our brain. It doesn't have to be all at once, but we want to use everything we have.

I need to ask myself, for example, why I decided to savage that particular unpleasant school teacher character in my story. It's my right to savage her–especially after how the real-life model treated me in first grade!–but might it not be more interesting to look at why she was such a martinet? Why was someone who hated children in a classroom anyhow? Had she been denied other opportunities (such as becoming a Marine drill sergeant?)

In order to re-see and revise, we might consider a few of the following approaches and techniques.

When you explore a character who is unlike you, focus on what you share. This is pretty obvious. I've written two first person novels in the voice of someone of a different gender and a different ethnic background from mine. I am not presenting them as great

successes,(that's someone else's call), but rather as approaches. First, the books are children's novels, and the narrator is a little boy in third grade. Children have very basic, very human concerns: Am I safe? Is this fun? I want a friend.

My character Marco lives in a single family household, but his mother works and goes to school, and he has a caring uncle who has a store up the street. I made a choice about the kind of child I was writing about: he wasn't a teenager just discovering sex; he was not abused; his mother wasn't addicted to drugs. He had good teachers in his school. He has challenges, but also tools to meet them. In fact, he's like the majority of working and middle class children in the United States, including those in poor neighborhoods.

Try the alternating third person. As a practical approach to the question of how to go into the lives of very different people, one good technique is to experiment with the third person limited rather than first person. For a novel or long story, many writers choose alternating characters' third person passages. This allows the writer to focus on what is important for the story. You aren't called on to create the entire detailed back story or the totality of consciousness of any one character. You can skip things of which you lack first-hand knowledge and can focus on Baldwin's "common history."

Also as a practical matter, need I say again that we are talking about second, third, and fourth drafts here, not the initial inspired outpouring?

The Denise Levertov solution. I was once at a large gathering of writers, and the poet Denise Levertov was asked how to become a more "political" poet. She answered, "Live a more political life. Writing with political consciousness will follow naturally."

Do research, formal or informal. If you don't want to change your lifestyle but do want to write about a character who goes regularly to political demonstrations, go to one yourself. Do research–if possible, in person, gathering sights and smells. This kind of research means having experiences. Learning from the inside out.

When I wrote the Marco books, I was in intimate contact with a real live third grader, my son. Moreover, I had worked for many years as a writer-in-the schools in New York City, and I had listened to children, and read their poems and stories and dreams. I had a lot of material to stimulate my imagination.

I was not writing about Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in Brooklyn. Nor was I writing about generic boyhood. I was writing about getting mad at your best friend, about being afraid of bullies, about losing your dog. I was writing about the specific details of one child's life

Write it from Your Own Perspective. Going back to Amy who tried to write about a lynching, I think perhaps the best approach for her as a twenty year old with no personal experience on the topic, would probably have been to write the story of what had moved and changed her. This probably would have meant eschewing the on-stage horror of the event. Sometimes–indeed, often–great violence and unspeakable things are best done off-stage. Amy might have dramatized what happens when a young white Southern girl discovers, say, the insignia of the Ku Klux Klan in her grandfather's trunk. Or, what if she imagines herself as a young white Southern girl in the nineteen twenties who discovers that a relative was present at a lynching--or worse. That might have been too personal, too grim, for Amy, but it might have been the deeper, more honest story.

Lillian Smith, a mid-twentieth century white Southerner wrote an interesting novel called Killers of the Dream. It ends with a lynching offstage that is reported from what amounts to a group point of view. Several citizens of a town, black and white, try to reach the jail where the victim is held, and fail. People hear distant crowd noises. Some hide. There are dialogue reports of what is happening. There are colors and sounds and smells. It's an indirect and powerful way that one white writer found to write about lynching.

Who should tell the story? But in the end, there is a question of whose story this is. Lillian Smith's novel opened new ideas and understanding to a lot of American white people. Similarly, however you might disdain Uncle Tom's Cabin as literature, it was never meant to give voice to Black people. Rather, it was a highly successful reaching out-- propaganda--to northern Christians, particularly women.

We are in a time now when we are at the beginning of many people telling their own stories. It isn't that William Styron was censored or should be for taking on Nat Turner--in fact, he published The Confessions of Nat Turner quite successfully, in spite of controversy. It's that it's now past time for non-white voices to try that story and a myriad of others.

A danger for any right-minded white writer (or white activist for that matter) is the tendency to make it all about me: how I discovered I had internalized racist ideas! Oh pity poor me! We're all the center of our own stories, but we have to ask what story we want to write. Maybe it's time for a comedy of white liberal cultural appropriation.

Two final ideas:

Try "wrong-side halvsies." That's a phrase used in some circles for people with a Jewish father and a mother who is not. What I mean by it is that one good way to approach those very different from us is to work at the edges, along the interface. This is actually where some of the most interesting things happen anyhow. A white woman who pretends to be black. Why did she do that? How fascinating?

I know a woman who thought she was white until she was in her forties and discovered that her father was a very light-skinned Black man who had been "passing" for decades.

I wrote a young adult story about a girl growing up in New York City with her mother, who never married her father, an Italian architect. Except for the most general category of race, this girl was entirely different from me, but I had a wonderful time playing what if: what if I had grown up in New York City? What if I had a weird obsession with Chinese pottery at the Metropolitan Museum? Go halfway: imagine a character who shares some things like you, and some that aren't. It's yourself with a different back story.

Give others substantial speaking parts. One small way for a writer to deal with these issues is to have people of other colors, genders, ethnic groups, ages, sexual preferences etc., when they appear as characters in our writing, talk at length. Even if it's a small part, this is very different from using a brown skinned victim solely to showcase the white main character's indignation and sensitivity. Rather, let people talk. One of the great things about fiction is how much can be told in dialogue, just as it is in real life. People sometimes take the stage and speak at great length, and this is one very small way to give voice to people unlike us.

You are still free! For me, a lot of these approaches and techniques act on my fiction writing the way the sonnet form and metered verse have acted on generations of poets: they help shape and discipline our imagination.

Creative writers of all stripes have the awesome privilege of using everything in their environment and their memory, in their imagination and in their time and place: the fly on a winter window sill; distant choir voices wafting out of a church; odor of falafel on the street; snow in the field; texts on the smart phone; headlines and massive gatherings in sports arenas and at demonstrations.

It's all ours. Everything, Anything.

A Response

Kate Gardner

My thoughts as a White woman and writer on your essay on cultural appropriation:

I think it is important for white-skinned people –who seem to be the primary audience for your essay –to understand and accept two things about themselves.

First, White people are racist -- which is different than being a racist). We can’t help it. We’re born into the fable of Whiteness, which is central to our country’s economic, social and cultural history and mythology. The sins of genocide and enslavement committed by our European ancestors and then justified through an invented White superiority and dehumanization of people of color have not yet been reckoned with. America has yet to take on the kind of Truth and Reconciliation Commission that played an important role in healing the psychic and relational wounds of Black and White South Africans.

As the contrarian humorist Fran Lebowitz spelled out in the 1997, “White people are the playing field. The advantage of being white is so extreme, so overwhelming, so immense, that to use the word “advantage” at all is misleading since it implies a kind of parity that simply does not exist.” White people don’t even realize the all-encompassing environment of assumptions that shape the way we see. They are so imbedded in our minds and culture as to be invisible to us.

We must, as White people, acknowledge and accept our complicity (however unwitting) and our lack of innocence –we must come to know our own human frailty.

Second, as one Black friend said to a White friend when asked what it was like to be Black, “You can never understand.”

So, we must also be humble and consciously shoulder our very human limitations and our blindness. We must understand that we are not omniscient and omnipotent.

Given this reality, I don’t think being a writer exempts us from shouldering some responsibility for engaging with the reckoning process that is transforming us and our readers. Afterall, true freedom comes with responsibility to each other –a lesson the Covid pandemic continues to hammer home. Freedom and responsibility are inextricable partners in adult life.

If a White person is going to claim the freedom of writing Black characters, they must ultimately also take the responsibility of going beyond their imagination –which has, after all, been shaped, like it or not, by a racist environment. If we want to write with any “truthfulness” on race – and by truthfulness, I mean the kind of genuine connection with ourselves and our readers that you are speaking of -- we must indeed change our segregated White lifestyle to engage with others. At the heart of the matter is Denise Levertov’s advice that to become a more “political” poet requires that we “live a more political life.”

Meredith, I don’t think it’s accurate to describe as “research” your raising a son and working intimately with a diversity of children in the NYC school system. That was a lived experience that changed you and how you see. Your consciousness was changed through your activity and the relationships you co-created.

Similarly, James Baldwin could write a powerful and “truthful” Giovanni’s Room because he had a lot of direct and intimate experience with White gay men. Those experiences became part of him and allowed him to genuinely express parts of them and himself through those characters.

It’s a tricky road. I deeply value the diverse friendships I have that help me navigate it. For example, I was recently able to check out a poem I wrote with a very thoughtful and longstanding friend to make sure I hadn’t simply written a White person’s stereotypical idea of Black people.

So, yes, writers, take on the challenge of writing characters different from you, but don’t limit yourself to what’s in that oh-so-imaginative head of yours, or even to all-important iteration. Get out there and have a real-life adventure with real people. If you want to write truthfully outside your comfort zone, then you need to step outside it and take some risks. But do it in good faith. Don’t just rip off someone else’s experience. Build relationships where you give what you have to others –including your privilege and blindness. Be a worthwhile companion. It will take time and investment –but it will change you, your writing and the world for the better.

The 99 Day Novel Course

by Alison Hubbard

Here’s some info on The 99 Day Novel course I took last fall through the Iowa Summer Writing Festival online. I had travelled to Iowa City twice for this festival a few years back, so I was receiving regular emails from them. The 99 Day Novel caught my eye because I was struggling to figure out how to move forward with RIDING OUT. The email came in August. There were two sessions. On the sign up day I logged in about an hour after it opened and both sessions were completely full! So this is the first thing. If you’re interested, sign up in the first minutes the class is offered. I put myself on a waiting list and as it turned out they opened up a third session.

Kelly Dwyer taught the courses. It was a boot camp for sure. There were nine three-hour sessions—sometimes two or three weeks apart, sometimes a week apart—from the “Marching Orders” class on September 2 through the last class on December 9. Mostly we used Alan Watt’s book, The 90 Day Novel, a highly organized, day by day method for writing a first draft. The first month is devoted entirely to daily writing exercises to clarify the characters, conflicts, and central theme of your novel. Watt believes in going from the general to the specific and “holding your idea loosely.” I found the exercises useful, and his words each day (ending with “Until tomorrow, Al”) very encouraging. At the end of the thirty days, as the final bit of prep before beginning to draft, Watt assigns an outline.

The second session of 99 Day was a month after the first. We were expected to have done all the prep work and exercises from the Watt and produced an outline. We were given a choice of outlines (Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat Beat Sheet, etc) but I chose the Watt. His outline is divided into three acts, each having about five points.

From then on, each session was an in-depth study of a particular topic, ie Character Arcs, Antagonists, Climax of the Novel, Ending of the Novel. We did brush over the elements of writing, POV, scenes, etc., but the thrust of the course was structural—getting the big picture and the story arc—and getting your first draft finished. Everyone was required to turn in something for each session. U of IOWA uses Canvas and we posted a few days before. The assignments were initially short, 500 words, but grew in length to 1500 words. My group was mostly from the West Coast and the Midwest. There were ten of us. Our projects ranged from a cozy mystery about a dog park killer to murders in the Eiffel Tower to a gay man’s wooing of a closeted priest (mostly in a high end restaurant. . .)

How effective was this? A major discovery for me was to move my story back in time from the 1980s to the 1950s. Following Watt’s advice not to go back and read until you finish, I produced a 205 page, 61,000 word draft between Sept. 2 and early January (a few weeks after the class ended.) When I finally did read the entire thing I realized there were many holes in the draft, although I liked the way it ended. In our class, I’m trying to fill in those holes and deepen the characters, mainly Frank. A lot of what I wrote in that first draft will probably be discarded, but writing it helped me to find some clarity on my book as a whole.

The amount of work people did varied. One woman was writing a book about some friends who graduated from high school in the Midwest. She worked on an outline the entire time. At first I was skeptical about this approach, but by the end the outline was very elaborate and the character arcs were clear. There was no pressure, people worked at their own pace.

If you’re interested, the website for Iowa Summer Writing is https://iowasummerwritingfestival.org.

One Story, Forty Submissions, Ten Years

By Ed Davis

Every now and then something happens in my writing life that so stuns or satisfies me that I need to share the wonder of it. Such a thing happened recently when I had a story published the same day it was accepted. That's remarkable but not nearly as important to me as the fact that it was accepted after 39 submissions over ten years!

DRUNKS AND MONKS

"Postulants" (re-titled from "Waiting for John") has religious elements—it's set at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky, and one of the characters is a monk-in-training who hasn't yet taken simple much less final vows. The protagonist, Martin, is an alcoholic with two months' sobriety, teetering on the edge of insanity and relapse. He's pinned his hopes on his college-student son John, who, after agreeing to meet his dad on this sacred ground, hasn't shown up, leaving Martin to fret and pace the grounds until he runs into a young postulant, with plenty of troubles of his own.

REWRITING AND RESURRECTION

I rewrote the story 40 or 50 times. At first John always eventually showed up for the climax. Recently I omitted him, believing that it was enough for Martin to confront only his son's surrogate, the postulant. Also, I cut a third of this 3,000-word story to make it fit a certain publication's limit. Still no luck. At that point, I almost gave up and banished the story to my fiction graveyard. But then something happened. During the final rewrite, John returned. Also, the ending had always required an image, the right image. It took me ten years to find it. Was it finally right?

UNFETTERED

I submitted "Postulants" to Agape Review, a "Christian-Themed" on-line journal (https://agapereview.com).What does "Christian themed" mean? According to AR's submission guidelines, "spelling it out would fetter your thought process. Rather, we will leave it to your imagination. If you aren't sure whether your work fits the bill, send it to us nevertheless and we'll get back to you." I like being unfettered and appreciated the implied openness. They got back to me—the day following my submission—to let me know my story had been published—not accepted: published. I felt like crying. An editor had at last seen value, spiritual as well as literary, in what had taken me ten years and countless rewrites, peer consultations and submissions to "perfect."

ALWAYS THE JOURNEY

It's a happy ending to a long season of doubt, even despair. And what did I learn? What comes to mind is stewardship: I simply shepherded the living "creature" entrusted to me to its natural home—in, of all things, a religious periodical, albeit a liberal-sounding and ecumenical one. Had its religious trappings played a role in keeping it from being accepted for so long? I don't know. Ultimately, I believe it was the writing itself, the thing I could—and eventually did—control: finding the right beginning and also the image with which to end, learning once again that it's the journey not the destination that's most important, in literature as well as in life. If you're interested (and I hope you are!) in reading "Postulants," here's a link to my story: https://agapereview.com/2022/03/29/postulants/

Some Thoughts and Exercises for Writing Physical Action

Writers who are naturals at dialogue and brilliant at structure and metaphor often have difficulties when their characters need to make a sandwich or kiss their lovers or strike out in a softball game. People write physical action in many ways, but the default is to describe it cleanly and smoothly, so that a reader can visualize what's happening and not have to waste time trying to figure out whose fist just smashed whose nose.

It is not as easy as it seems.

Here's an example that is plain and brief and cinematic in its small way. It was, in fact, transferred almost gesture by gesture to film.

The Don, still sitting at Hagen’s desk, inclined his body toward the undertaker. Bonasera hesitated then bent down and put his lips so close to the Don’s hairy ear that they touched. Don Corleone listened like a priest in the confessional, gazing away into the distance, passive, remote. They stayed for a long moment until Bonasera finished whispering and straightened to his full height. The Don looked gravely at Bonasera. Bonasera, his face flushed, returned his gaze unflinchingly.

-- Mario Puzo, The Godfather, p. 30

Love that detail of the hairy ear.

In general, physical action-- whether making tortillas or running for a bus or slashing with a knife, whether about making love or committing a murder-- works best when it is simple and sharp. The fewer words the better. Obviously this is a rule that has been broken often and to good effect, but start by trying to transfer what you see in your mind simply and clearly to the reader's mind.

One excellent technique to help you do this is to close your eyes and actually visualize the scene you have drafted or are about to draft on a screen. Watch your characters do their actions on the screen, and then write what you saw.

Here are links to two passages of action. The first one is a classic not-so-artistic passage of action from an old cowboy novel. It feels long and loose now, but Louis L'Amour was extremely popular in the last century, and this was what his readers loved. The second one is rather poetic, but also very easy to visualize. It also is about the narrator's experience, and and her feelings about dance and her dance teacher.

A Fist Fight from an old Louis L'Amour Novel

He Goes She Goes

A Physical Action Writing Assignment

Set a timer for 3 minutes. Write about a character in your novel running. If you don't have such a scene, add one--maybe from the part you haven't written yet.

The character may be fleeing danger or trying to make a plane or in a competition or playing with a pet. Write for 3 minutes seeing the action from the outside, concentrating on the movements and sounds, possibly using the screen technique above.

Set the timer again for 3 minutes. Write it from the inside. Concentrate on what the running feels like: feet pound? Lungs burn? Does the person fall?

Ed Davis on Recycling Your Material

Ed Davis writes that his story "Bend the Knee," published in Still: The Journal (#30, Summer 2019), "was salvaged from a failed novel Old Growth. After OG was rejected by a university press and an agent I respect, I embarked on a process of literary recycling. Since I'd already written a sequel to OG, I basically folded several of the best chapters of OG into the sequel as dramatized backstory.

"This involved expositional underpinning and summary of the missing chapters as the narrative moves backward and forward in time between OG and its sequel. As a result, the older material has gained renewed energy in the context of the brand-new, untried story. It feels like it's working. The process hasn't been easy—but neither is turning a novel chapter into a stand-alone short story, either. The true test of success will come when my beta readers weigh in"

Read the story "Bend the Knee" here.

A Brief Note on Changing Names as Character Development

One technique for developing character is to choose a character you're having trouble with, and change the name. It can be a major or minor character. Maybe you just feel you haven't captured him or her yet. Try going through with your search-and-replace word processing function, and changing the character's name.

Now do it a second time with a different name, trying to find one that feels right for the personality but also is appropriate for the historical time and possibly the ethnic background of the person--although a name that defies expected backgrounds can work too. This process can help you focus on who the character really is. In a piece set in contemporary times, you can use almost any names, but historical novels, in particular, probably need names that were actually used at the time.

For example, in a new project set around the turn of the twentieth century, I had begun with my main character's daughter having the name Eleanor after her grandmother. At first she's just a baby, but as she gets older in my narrative, especially as she approaches adolescence, she began to seem spiritual and self-sacrificing. Clara felt right, so I changed the name to Clara.

But the more I wrote, the more she took shape, and Clara began to seem too ethereal for her. She was determined or even stubborn rather than spiritual (and thus more useful to the world, probably). So I renamed her Julia. At the moment, she's Julia Eleanor Rosedale. It feels pretty good, but I'm still drafting.

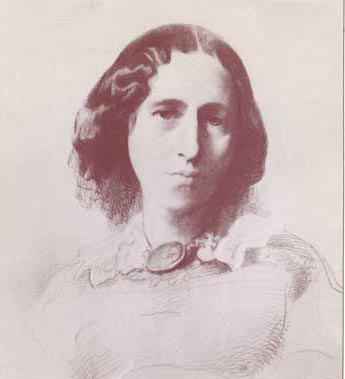

From Middlemarch George Eliot From The Mill on the FlossFive Lessons from George Eliot:

Celebrating Her 200th Birthday 11/22/1819

(With writing exercises)If you don't know the story of George Eliot's life, it is worth a novel in itself: her religious rebellion; her unconventional

twenties as a single woman trying to earn a living editing and translating; how she finally met a man who fully supported her work, but could not marry her because of what now seem like ridiculous divorce laws; how she and he considered themselves married by their own commitments and morality; how the rest of the world did not; how she became one of the most famous and morally influential writers of her century. Indeed, a lot of us believe that her novel Middlemarch may be one of the five best novels ever written in English.

You may or may not have the patience for the long descriptions and pontificating of nineteenth century fiction, but if you haven't read George Eliot, at least give her a try. A good place to start is The Mill on the Floss. It has a feisty girl protagonist whose fatal flaw is that she wants too much to be loved, especially by her honorable but rigid and self-righteous brother. It paints a splendid picture of life in rural England in the first half of the nineteenth century and has a satisfyingly melodramatic climax (see illustration).

But Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss are recommendations for reading. What does Eliot have to suggest to us about writing?

Lesson I:

This first lesson is not exclusively from George Eliot, but rather from all the best nineteenth century novelists (the Russians, the French, certainly the English). These writers believed that everything can go into fiction. Nothing is forbidden--not teaching moments or philosophical speculations. I strongly recommend that at least in your first draft, you should reach out broadly. Don't hesitate to include religion or current events or scandals of the day along with the close-focus of physical detail and internal experience. Include dreams and recipes and baseball box scores if the spirit moves you.

This is not, of course, to suggest that you write a story strictly to push a particular political or religious belief. That isn't fiction but rather journalism or an op-ed piece. The point is that these are part of real life, and prose narrative in its many ways tends to be about real life--even when it is fantasy or science fiction or horror.

I consider it enriching to your fiction to give a character some of the doubts and queries that may run through your own mind. You can do this in monologue or dialogue. Sex and violence and descriptions of weather and meals are all part of fiction, but so may be discussions about politics and work

One of George Eliot's novels, Felix Holt: Radical is set firmly at a time of labor unrest in England. She was interested in how a change in the law (the First Reform Act of 1832) would affect workers and farmers as well as in the terrible secret of one of her characters. She sometimes goes off on not-so-little tangents that show off her learning (probably in more detail than a twenty-first century reader appreciates), but the point here is that you can use everything in even a lean, minimalist story. Put the events or ideas in dialogue or have a television in the background of a bar. Have your main character mull over the big issues as we sometimes do in real life.

Exercise 1: This is another of those all purpose exercises for restarting a stalled story or book, or to get more material. Have your main character hear something on the radio or see something on TV or on the smart phone, some world event or famous crime. You can use this to ground the story in its time and place (which impeachment hearing is this?), but more importantly, What does it mean to your character? How does the character react, if at all? With anxiety? With cynicism?

Exercise 2: Think about the media your characters are using. Are there thematic news stories that can add to the mood and ambiance? If your story is set in 1976-77, for example, how do your characters react to the Son of Sam serial killings?

Exercise 3: Rather than have your protagonist react internally to the events, have them come up in conversation before class, at the dinner table, etc.

Lesson II:

Eliot is famous for her awareness of and appreciation of farming and the lives of farmers of various social levels. One of the things we often leave out of our fiction is work--that is to say, what people do day-to-day. Obviously you don't just write little essays about how things are done and set them in the middle of your fiction undigested, but anything in which you have interest or expertise can enrich your fiction. It may lead to some plot element, or it may lead to a deepening of the main character or a minor character. Phillip Roth has wonderful descriptions of glove-making in American Pastoral. It is part of what his main character does in his everyday life, and it eventually takes on symbolic meaning.

Exercise 4: Have a character watch her grandmother make tortillas (or do some other work with the hands): break down the physical action, mention the rich odor, the slapping sound. Or, give a character a job as a car salesman--What are the little tricks to keep up the customer's interest. Does the character like the challenge or hate the job? In other words, include your characters' professions or jobs.

Lesson III:

Eliot tends to use the omniscient viewpoint. She uses it very well, as do many of the nineteenth century novelists, but she always stays close to one character long enough to capture the full emotional depth of what that person is going through before pulling back to an overview or the next character. This is the essential challenge with the omniscient viewpoint. It is too easy to move around too much, creating a kind of narrative vertigo. Be sure you stay with one character long enough to learn something about him or her.

Exercise 5: If you are working with the omniscient viewpoint, experiment with following some peripheral character and following them very closely for a while--longer than you might without the special instruction. Choose a figure that almost disappears in the background. Maybe it's a dark gray city rat with a broken tail hurrying to the drain with a piece of pizza. Once you start following the rat, let us feel its struggle with the big piece of pizza. Is it a mother with hungry pups? How does the world look at drain level?

Lesson IV:

Our most vivid sense impressions probably happen when we are very young. This is one reason people often write successfully about their own childhoods. When we are small, many things are Firsts, and our senses are open and sharp. George Eliot wrote till her death about people in farm landscapes similar to the one she grew up in.

I'm not suggesting you suddenly put a toddler in your story (although that might be fun to see what happens) but rather that you use your characters' senses with the vividness of a child.

Eliot's probably least popular novel today is called Romola, and it is set in fifteenth century Florence. I didn't like it the first time I read it--I could feel her research weighing down the story, I thought. But then I read it again years later, after I actually visited Florence, and it suddenly lit up for me. I had my own sense impressions of the place that added to the book. I was also older, and the book's strengths are its portraits of traitors and turncoats: it isn't a cheerful book.

So the lesson is the importance of vivid sense impressions for making our fiction alive for ourselves and readers. Whether we've got a detective being beat up by bad guys or a child tasting bread hot out of the oven, we will go deeper into our created world and bring readers with us when the sense description is sharpest. Not longest, note, but most vivid.

Exercise 6: Go back to some scene you are having trouble with. Re-envision it with your eyes closed, starting with your senses other than seeing. Get some details of touch and the sensation of breeze or dampness in the air. What music is playing in the car down the street? What do you smell? Give these observations to one of the characters in your story, or just set the scene differently. Does it change what happens?

Exercise 7: Okay, try putting a toddler in your story! Maybe it's a child being smacked in a public place. How does you character react? Maybe it's a lost child, or the main character's family member. What does this stir up? Change about the plot? Daughters have become a cliché for tough guy thrillers and detectives. They are always getting kidnapped or threatened! You can borrow the cliché or try something different with the kid: humor? Disturbing a stake-out? Reminding the hero how much she doesn't want to have children of her own?

Lesson V:

Write what fascinates you, or don't bother. Eliot was through-out her life highly sensitive to criticism--pretty neurotic about it, really, to the point that her partner wrote letters to friends asking them not to send comments on her publications. She suffered during the process of writing a new book over how bad she thought it was, and dreaded reviews.

At the same time, while she accepted technical and stylistic suggestions, she always wrote what she wanted to. She had the good fortune to write in a way that led to great popularity and financial success, but she didn't seek popularity. She wrote to find out what her characters were really like, and she often surprised her readers, and possibly herself, about the depths of characters that in another writer's hand would have been caricatures.

For example. Maggie Tulliver's mother in The Mill on the Floss is a ridiculously superficial woman who is far more concerned about her beautiful linens and Maggie's unruly hair than about the child's moral or intellectual development. Still, as the story goes on, and after the family suffers heavy financial setbacks (and her beautiful linens have to be sold), she is faithful to her family, and more importantly, when Maggie suffers the the deepest social disgrace, she sticks by her.

Dickens would have handled it differently. He had one of the most amazing imaginations every employed in fiction writing, and his characters are so wonderful with their memorable tics and catch phrases, their inimitable names, extreme behaviors and large gestures. But in general, they don't change a lot.

Eliot, on the other hand, believed that the function of a novel is, among other things of course, to chart the gradual changes people go though from start to finish. She turns her characters before us as on a potter's wheel, gaining form, expanding here, narrowing here.

Exercise 8: Put yourself in a quiet mood. Play some wordless music softly, or do slow breathing, or whatever it takes to quiet yourself. Close your eyes and think of all the writing projects you've started. If they are still on the

computer, imagine they are printed out or even published, and arrange them (in your imagination) on a table in front of you, or as books on a shelf, or a list. What have you not written? Is there a subject you are interested in that never seemed appropriate for a story? A character who always fascinated you? A plot that came to you when someone told you a story? (Henry James's

The Turn of the Screw was given to him at a dinner party; Tolstoy's Anna Karenina came from a newspaper clipping). Set a timer for fifteen minutes and write as much as you can about that plot or character or idea.

Final Thoughts on George Eliot:

George Eliot made a lot of money writing. In fact, she managed to save her partner George Lewes's financial bacon (he was responsible for his own children with his legal wife as well as his legal wife's several children by another man). Eliot made enough to create a very comfortable life for herself and Lewes, and to give all his children good starts in life.

But she (and Dickens and Thackery and Trollope and Mrs. Gaskell and all the Victorians) had a great advantage over us now which was that the reading public was growing and buying. The buying is particularly important, because you could make a tidy fortune writing stories and novels. The Victorians wrote at the height of the time when novels and poems had relatively few competitors for the middle class entertainment shilling. Yes, there was theatre, if you were in London, and certainly there was socializing and sport and church, but the particular pleasure of being entertained with stories was all on the page. People read potboilers, and they read high art with equal enthusiasm: they had time and inclination and wanted to read.

Or to be read to--one typical way of consuming novels used to be around the lamp in the evening, the ladies perhaps doing their "work" with needle and thread, and one person chosen to read to all of them. Books were rented, borrowed, and bought in periodicals and cheap editions.

Today we have what my mother would have called a hard row to hoe. That is to say, some of you may write novels that are just what the public is hungry for, and you may get a movie deal, and you may actually get rich writing--and if you do, my most sincere congratulations! But more of us today end up with small press publishers or alternative, independent publishing careers. Some of you may never make a career of it at all, perhaps writing a handful of powerful short stories.

You can't be guaranteed a living from turning out a certain number of pages or words, but you can still take writing lessons from George Eliot, especially the part about writing what you really want to write.

Make the act of finding your story and gaining insight into your characters, and working out your ideas through fiction an end in itself.

Structuring with the Raised Relief Map Technique

For short stories and even novellas, I am trying a new way of drafting. I have always read over and organized my notes and rough drafts of scenes and passages of narration before I started a "real" first draft, but I've begun to do it in a more formal and disciplined way.

Instead of my usual process of slipping as quickly as possible deep into the words, I pull back a little first. I begin with some left brain work that doesn't sink into the creative depths. This sounds counter-intuitive, especially as the going-deep is what attracts most of us to writing, but not-sinking-in is actually the discipline here. I've already been inspired to write the various rough bits, and now, for a little while, I avoid inspiration and instead try to tidy up the material. Again, this is nothing new except for when I am doing it, which is early on.

I scrape the extremely rough drafts of scenes, the scraps of dialogue and description, into digital heaps and shove them around until I have a little landscape of homemade hills. I give the piles temporary names, which probably won't be there in the finished version: The Book Club; Bobby One; The Psychiatrist; Bobby Two. The heaps, the hills, serve the same function as the "rules" of a genre story: a formula to change and ignore. I use it as the biographer uses the chronology of a life, as a rough guide. The form is not a choke collar or a cage, but a landscape to wander in and discover.

After the heaps, I go back to the beginning and write in my normal way, letting one thing lead to another, letting myself sink into the scenes and ideas and sensations.

This is not, by the way, the same as a clean start, which I recommend to myself and others when there seems to be major confusion and too much material. In a clean start, you begin with an empty screen or blank sheet of paper. Having no notes in front of you allows your mind to edit on its own. It brings back only the best parts of what you've already written, and you usually get a leaner, cleaner, altogether better draft into which you can, of course, put anything good from the old one.

The raised relief map technique preserves the materials but groups it into a sort of map. You can climb the high points, make side trips, stop to smell the flowers. You can be surprised by what is hiding in a cave or an old mine shaft. You can excavate or wander off, and then come back to the path or make a new one.

How, you might ask, do you find the direction?

My best hope is that the very wandering and exploring will give it to you, but also, ideally, when you made the heaps in the beginning, you were looking from your cool distance at where the pieces might go. Thus, the hills should have a natural progression, a hypothetical story structure: lowest to highest, maybe with a climax in the middle. In other words, you chose the general path when you first heaped up the extremely raw notes. Now you take that general direction, with leisurely side trips as you write.

The extended metaphor begins to break down here: the idea is to plan and structure the story line early on. Anyone trying this should jettison it as soon as it feels the least bit restrictive rather than formative.

The technique is pretty straightforward with a short story or even a long story or essay, because usually there are only six or eight of the heaps of ideas and materials. It is more challenging, or at the very least more time-consuming, with a novel.

Need I reiterate that this is something to play off of, not get stuck in? The plan may change radically before you're done, but for the moment, you have (1) an excellent way to see what you have, the lay of the land; (2) at least a hypothetical structure; and (3) lots of material ready to expand and explore.

(By MSW, with suggestions from Joan Liebowitz, Carole Rosenthal, and NancyKay Shapiro)

Rolling Revision: The Interplay of Big Picture and Close-Up

Writers often come to prose narrative from a place of having a story to tell--or, conversely, from their sheer love of language. Obviously, the best prose of any genre combines both things--an idea, a shape, and also graceful choices of phrase. You hear writers praised for the rhythm of their sentences, and you hear them praised for the power

ful momentum of their stories.

Beginning writers tend to fall into two categories: some get completely caught up in polishing their sentences and their first page, and after a while despair of ever finding a direction let alone completing the work. The other type of beginning writer sketches out a terrific plot and vaguely imagines that someone else--a hired editor, the prop person for the movie version--will fill in the details.

Those of us who have been writing for many years usually recognize these tendencies in ourselves and consciously or unconsciously compensate for them. I think I do my best writing when I am aware of the requirements of the manuscript and of my own needs at a given moment. Thus, if I am distracted by life's daily business (a class to teach! an upcoming medical procedure! preparing a holiday dinner for nine!), I still try to write, but I do a particular kind of writing. When I only have a half hour, I've found that I can always do a little sharply focused detail editing, or I can dash off something wildly new or surreal. I'll daft an incident from my childhood, or a dream or a scrap of overheard conversation with no relation to my present writing project,

What doesn't work for me when I'm distracted is the kind of deep work that happens on my best full writing days. Then I begin perhaps by tinkering with the paragraph where I left off on my last writing session (close-up work). Next, as I continue with something new or a little more revision, I might get a new idea--a flash of insight (But wait! What if he knew that earlier on?) Then I rough in a new scene two chapters earlier, which requires adjustments to my outline. Next I would work on the outline for a while, maybe breaking a chapter into two chapters, which means some mechanical renumbering. I might also run through the chapters to see if my new material requires any "continuity" work to make things match up.